“The human psyche is shaped by the interplay between inner drives and outer cultural forces. For every dominant social pattern, the unconscious generates a compensatory movement, seeking to restore balance and wholeness. By understanding these cultural-psychological dynamics, we can work towards greater self-awareness, social responsibility, and holistic well-being.”

-Alfred Adler

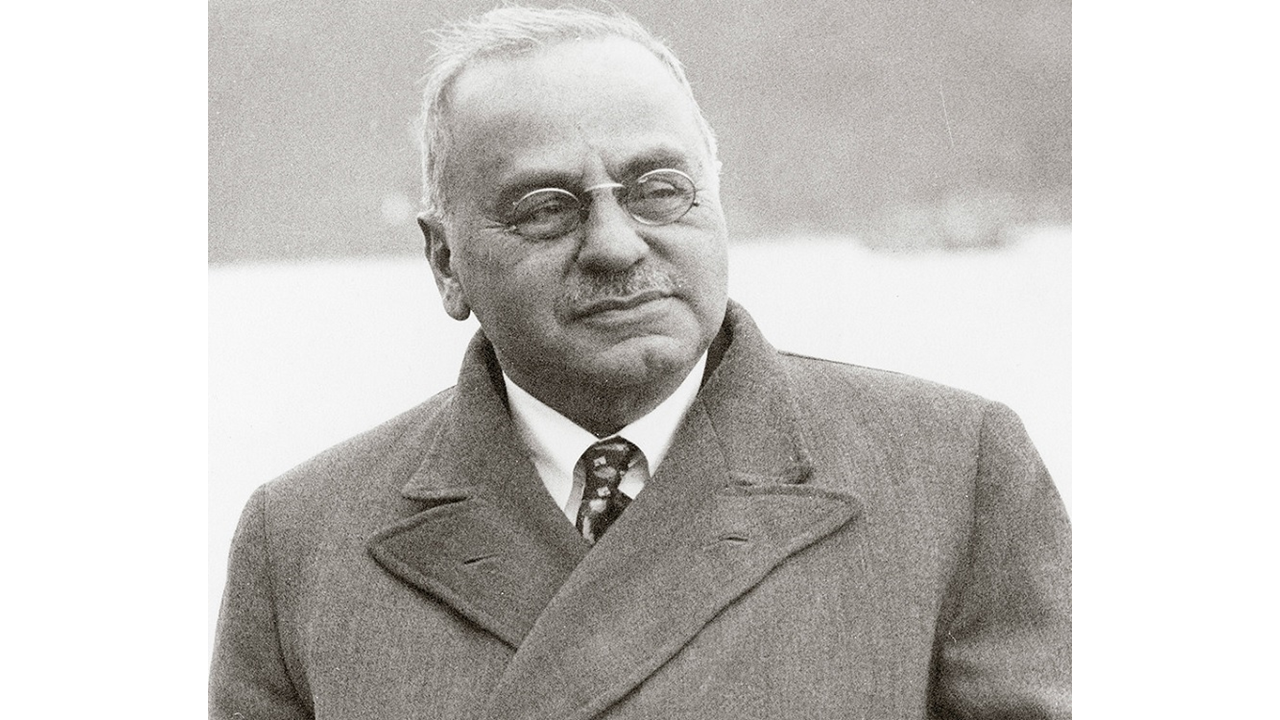

Who Was Alfred Adler?

Alfred Adler (1870-1937) was an Austrian medical doctor, psychotherapist, and founder of the school of Individual Psychology. Along with Freud and Jung, Adler was one of the key pioneers of depth psychology in the early 20th century. However, Adler’s unique theoretical contributions have often been overshadowed by his more famous counterparts. In many ways, Adler was ahead of his time, anticipating later developments in humanistic, existential, and socially-oriented approaches to psychology.

Adler began his career as an ophthalmologist before shifting his focus to psychiatry. He was an early member of Freud’s circle in Vienna, but broke away to develop his own school of thought around 1911. Adler called his approach “Individual Psychology” to emphasize the unique and indivisible character of each person, in contrast to Freud’s division of the psyche into id, ego, and superego.

Main Ideas and Key Points:

- Individual Psychology views the person holistically, as an indivisible unity of thinking, feeling, and acting.

- Adler pioneered the idea of the “creative self” – the active, meaning-making center of the personality that interprets and makes use of all experiences.

- A central concept in Adlerian theory is the “striving for superiority” – the innate motivation to overcome feelings of inferiority and to perfect oneself.

- Adler saw the “inferiority complex” as the root of many neuroses. When natural strivings for growth are blocked, they can turn into exaggerated concerns with status and power.

- In contrast to Freud’s emphasis on past causes, Adler focused on the purposive, future-oriented nature of human behavior. Symptoms and behaviors are seen as “safeguarding strategies” aimed at protecting the self and moving towards an ideal.

- Adler held that the psyche is shaped by the interplay of “organ inferiorities” (physical weaknesses that spur compensatory growth) and environmental influences, especially early family constellations and birth order.

- Dreams are understood as an expression of the individual’s “life style” – the unique pattern of attitudes, beliefs and behaviors that move the person towards their fictional final goal.

- Adler placed great importance on the human capacity for social feeling and “Gemeinschaftsgefühl” – a sense of solidarity and identification with the larger community.

- Psychological disturbances are seen as an expression of “discouraged” striving, often reflecting a lack of confidence and social feeling.

- The therapeutic relationship is viewed as a collaborative partnership aimed at uncovering the individual’s life style and enabling a more conscious, flexible, and socially-oriented approach to the tasks of life.

- Adler emphasized the importance of equality, empathy, and mutual respect in all human relationships, and was a forerunner of feminist approaches to psychology.

- Adlerian ideas have been influential in later humanistic, cognitive and systemic approaches, and have found wide application in education, parenting, leadership and social reform movements.

Adler, Freud, and Jung: Three Views of the Unconscious

To understand Adler’s distinctive approach, it is helpful to contrast it with the views of Freud and Jung, his contemporaries and rivals in the early psychoanalytic movement.

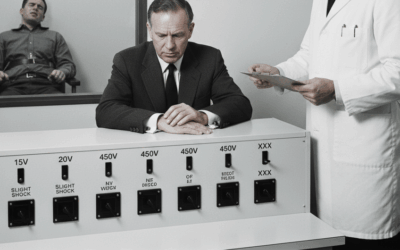

Freud’s model of the unconscious was heavily shaped by 19th century physics and hydraulics. He viewed the unconscious as a kind of “trash can” or cellar of the mind, a dark repository of repressed memories, forbidden wishes, and primitive drives. In Freud’s early formulation, the unconscious was primarily a site of pathology, a churning cauldron of “the repressed” that constantly threatened to burst into consciousness and disrupt the fragile civilizing veneer of the ego.

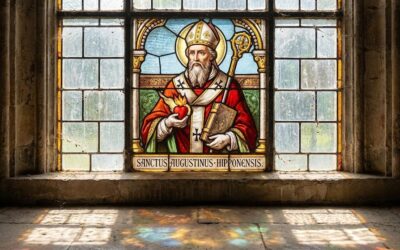

Jung, in contrast, saw the unconscious as a creative matrix that was the very source of consciousness and individuation. For Jung, the personal unconscious was only the top layer of a much vaster collective unconscious, a timeless repository of universal symbols and archetypes. Jung’s unconscious was a borderless realm that connected the individual to the evolutionary origins of life and the mythic foundations of culture. Dreams, from this view, were not just a “disguised fulfillment of repressed wishes” (Freud) but direct and symbolic expressions of the timeless patterns that shape human nature.

Adler’s view differed significantly from both Freud and Jung. For Adler, the unconscious was neither a trash can of the repressed nor a mystic ocean of archetypal forces, but a pragmatic “processing system” that generates compensatory fictions and safeguarding strategies to help the individual adapt, survive, and thrive in their social world.

Adler observed that for every dominant cultural pattern or expectation, the psyche tends to generate an internal counterpart or “compensation.” These compensatory dynamics help to maintain a functional balance between the individual and their environment. For example, in a culture that overvalues toughness and invulnerability, the unconscious will likely produce more fantasies and symptoms related to weakness, vulnerability, and dependency. The repressed “other side” serves to complete the one-sided picture and remind the individual of their full humanity.

From an Adlerian view, the unconscious is not a literal place or separate realm, but a set of self-organizing processes that are always in dynamic interaction with the conscious self and the social field. The goal of these unconscious processes is not wish fulfillment or individuation per se, but the “safeguarding” of the self-ideal and the person’s core assumptions about life, often formed in early childhood.

Symptoms and neuroses, in this light, are not just products of instinctual conflict or failed repressions, but creative (if costly) attempts to bridge the gap between one’s actual lived experience and one’s idealized self-image. A person who struggles with compulsive hand-washing, for instance, may be unconsciously compensating for feelings of moral impurity or social alienation. The symptom “safeguards” their self-worth by magically undoing the perceived contamination and symbolically rejoining the social world.

Adler’s model of the unconscious as cultural compensation deeply informed his approach to psychotherapy. Rather than seeking to uncover buried memories or integrate disowned archetypes, the Adlerian therapist works to illuminate the individual’s “life style” – the implicit worldview and default template for living that shapes their perceptions, behaviors, and symptoms.

By bringing this “hidden logic” of the self into dialogical awareness, the therapist helps the client to understand how their problems originally made sense as attempts to cope with or compensate for the difficulties of their situation. This empathic insight opens the door to more conscious and flexible ways of meeting life’s challenges and pursuing one’s valued goals, beyond the narrow grooves of the existing life style.

Though lesser known today than Freud’s “depth” model or Jung’s “height” psychology, Adler’s socially-embedded view of the dynamic unconscious anticipated many later developments in cultural psychology, systems theory, and cognitive approaches. Adler’s unconscious is not a submarine netherworld or archetypal pleroma but the “unseen background” of the individual’s lived world – the implicit contexts, stories, and strategies that shape experience from within. By making this “unseen background” figural, Adlerian therapy aims to free up the person’s creative capacity to reshape their life in more fulfilling and socially-responsible ways.

Freud, Adler, and the Politics of Psychoanalysis

To appreciate Adler’s intellectual and professional trajectory, we must situate it within the contentious politics of the early psychoanalytic movement.

Adler was one of Freud’s earliest collaborators and an influential member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society in its formative years. However, his relationship with Freud was fraught from the start. Adler’s background as a socialist physician working with the underprivileged contrasted sharply with Freud’s bourgeois clientele and apolitical stance. Adler emphasized the impact of social conditions and power dynamics on psychological development, while Freud tended to downplay external factors in favor of intrapsychic drives and conflicts.

These differences came to a head as Adler began to articulate his own ideas about the nature of the psyche and the aims of therapy. Adler challenged Freud’s libido theory, his dualistic model of the life and death drives, and his insistence on the centrality of the Oedipus complex. In contrast to Freud’s biologism, Adler proposed a more flexible, socially-oriented view of human motivation centered on the striving for superiority, the impact of birth order and family dynamics, and the importance of social interest and community feeling.

Freud, who demanded strict loyalty from his followers, responded to Adler’s innovations with a mix of admiration and rivalry. In 1910, Freud anointed Adler as president of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society and his heir apparent in the psychoanalytic movement. However, just a year later, as Adler’s divergence from orthodox Freudianism became more apparent, Freud abruptly turned against him.

In a series of heated debates within the Vienna society, Freud and his allies attacked Adler’s ideas as a threat to the integrity of psychoanalysis. They accused Adler of watering down psychoanalytic theory, neglecting the role of sexuality, and introducing a “self-psychology” that was more akin to American pragmatism than depth psychology.

Adler, for his part, stood his ground and continued to develop his alternative approach. In 1911, after a final showdown with Freud, Adler and several colleagues formally broke away from the Vienna group and established the Society for Free Psychoanalytic Research, which soon became the Society for Individual Psychology.

This split between Freud and Adler was the first major schism in the psychoanalytic movement, foreshadowing Jung’s later break and the proliferation of competing schools in the following decades. It also established a pattern in Freud’s dealing with dissident pupils that Frederick Crews, the noted Freud critic, has called the “politics of exclusion.”

As Crews documents in his historical study “Freud: The Making of an Illusion,” Freud had a penchant for anointing brilliant young disciples as his heirs and successors, only to turn on them viciously when they dared to question his theories or authority. This was the fate not only of Adler and Jung, but also of later defectors like Otto Rank, Sandor Ferenczi, and Wilhelm Reich.

In each case, the “crown prince” would be raised to prominence within the movement, celebrated for their contributions and loyalty to Freud, only to be abruptly demoted and denounced as a heretic or “wild analyst” when they began to articulate their own original ideas. Freud would mobilize his allies to isolate and discredit the dissenter, often resorting to ad hominem attacks and questioning their personal and professional integrity.

This pattern, which Crews attributes to Freud’s narcissistic grandiosity and intolerance of criticism, had a chilling effect on the intellectual development of psychoanalysis. It enforced a culture of orthodoxy and deference to Freud’s authority that stifled creative innovation and open debate. Many of Freud’s most gifted pupils, like Adler and Jung, were forced out of the movement prematurely, taking their insights and potential contributions with them.

Adler, to his credit, refused to be silenced by Freud’s attacks or drawn into a polarizing battle. He continued to acknowledge Freud’s genius and the value of many psychoanalytic concepts even as he developed his own distinct approach. Adler saw individual psychology not as a radical repudiation of Freud’s work, but as a complementary perspective that expanded the scope of psychotherapy beyond the intrapsychic to include the social and interpersonal dimensions of human existence.

In this sense, Adler was a forerunner of the integrative and eclectic approaches that would come to dominate psychotherapy in the late 20th century. He anticipated the turn towards a more relational, culturally-sensitive, and context-aware understanding of psychological dynamics. Adler’s break with Freud, though painful on a personal level, freed him to create a more flexible and humane approach to therapy that has had an enduring influence on modern practice.

However, Adler’s expulsion from the psychoanalytic mainstream also contributed to his relative marginalization in the history of psychology. As Freud’s star rose and psychoanalysis became a cultural juggernaut, Adler’s contributions were often overlooked or absorbed into other traditions without proper attribution. It is only in recent decades, with the waning of Freud’s reputation and the growth of integrative approaches, that Adler’s true stature as an original thinker and pioneering clinician has begun to be appreciated.

The Influence and Legacy of Adler: An Unsung Pioneer

Despite his pivotal role in the early history of depth psychology, Alfred Adler remains the least well-known and celebrated of the great pioneers, especially compared to Freud and Jung. There are several reasons for this relative neglect, which we’ve already touched on: Adler’s early break with Freud and the psychoanalytic mainstream; his emphasis on social and interpersonal factors over intrapsychic drives; his more pragmatic and common-sense approach to therapy; and the absorption of many of his ideas into other traditions without clear attribution.

However, a closer look at the history of 20th century psychology and psychotherapy reveals the profound and pervasive influence of Adler’s thought, often in unacknowledged ways. Many of the core themes and practices of humanistic, cognitive-behavioral, family systems, and community-oriented approaches were pioneered or prefigured by Adler, even if they developed largely independently of his direct lineage.

In the humanistic tradition, Adler’s ideas about the creative power of the self, the importance of meaning and values, and the centrality of the therapeutic relationship anticipated the work of thinkers like Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Rollo May. Maslow’s concept of self-actualization as the highest human need echoes Adler’s notion of striving for perfection. Rogers’ emphasis on unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding in therapy mirrors Adler’s collaborative and encouraging stance. May’s existential view of anxiety as the confrontation with possibility and freedom resonates with Adler’s teleological view of neurosis.

In the cognitive-behavioral realm, Adler’s focus on beliefs, assumptions, and schemas as the drivers of psychological problems foreshadowed the work of Aaron Beck and Albert Ellis. Adler’s concept of “basic mistakes” – the irrational ideas that shape maladaptive life styles – is a direct precursor to Beck’s “cognitive distortions” and Ellis’ “irrational beliefs.” Adler’s emphasis on challenging and correcting these mistaken notions in therapy laid the groundwork for the cognitive restructuring techniques at the heart of CBT.

In the family systems field, Adler was a pioneer in recognizing the formative impact of birth order, sibling relationships, and family atmosphere on individual development. His appreciation of the recursive feedback loops between individual symptoms and family dynamics anticipated the core insight of systemic thinking. Many of the concepts and techniques of experiential family therapy, such as reframing, paradoxical injunction, and role-playing, have clear roots in Adlerian practice.

In the realm of community psychology and social psychiatry, Adler was far ahead of his time in emphasizing the essential role of “social interest” and “Gemeinschaftsgefühl” (community feeling) in mental health. His vision of therapy as a way of empowering individuals to take responsibility for their lives and contribute to the common good anticipated the values of the community mental health movement of the 1960s. Adler’s social activism, his egalitarian and de-stigmatizing approach to patients, and his emphasis on prevention and public education all prefigured key principles of contemporary community-based practice.

Beyond the clinic, Adler’s ideas have had a wide impact on fields like education, parenting, leadership, and social reform. His emphasis on encouragement, democratic collaboration, and the promotion of social interest anticipated the learner-centered and cooperative models of education that gained prominence in the late 20th century. Adler’s insight into the role of birth order and early family dynamics in shaping personality has become a mainstay of popular parenting literature. His appreciation of the inferiority complex and the striving for superiority foreshadowed many contemporary theories of motivation and leadership. And his vision of psychology as a tool for advancing social justice and human welfare inspired generations of activist-scholars and practitioners.

In all these ways, Adler’s influence has been quietly pervasive, even if his name is less celebrated than some of his contemporaries or successors. His ideas have seeped into the groundwater of modern psychology and culture, nourishing the growth of a more humane, contextual, and socially-conscious understanding of human nature and potential.

However, Adler’s relative marginalization in the history of psychology also reflects some enduring biases and limitations in the field. Adler’s emphasis on the social embeddedness of the psyche, his appreciation of the subjective and teleological dimensions of experience, and his vision of therapy as a collaborative partnership all challenged the dominant natural science paradigm of his time (and ours).

Adler’s holistic and integrative approach, while prescient in many ways, has often been overshadowed by the more reductionistic, mechanistic, and specialist tendencies of mainstream psychology. His optimistic and melioristic view of human nature, with its emphasis on our capacity for growth, creativity, and social contribution, has sometimes been dismissed as superficial or naive compared to the “deeper” and more pessimistic visions of Freud or Jung.

Moreover, Adler’s pragmatic and common-sense style, his use of everyday language and examples, and his focus on practical solutions rather than grand theories or technical jargon, have sometimes been seen as a liability in a field aspiring to scientific rigor and specialization. Adler’s accessible and demystifying approach to therapy, while appealing to many clients and practitioners, has not always been valued in academic circles or psychoanalytic subcultures that prize esoteric terminology and complex interpretive schemas.

Yet, in many ways, it is precisely these “weaknesses” that constitute Adler’s enduring strengths and relevance for our time. In an era of increasing specialization, fragmentation, and abstraction in psychology, Adler’s holistic and integrative vision offers a much-needed corrective. His appreciation of the creative and meaning-making capacities of the individual, always in dynamic interaction with social and cultural contexts, provides a rich foundation for a more fully human science of persons.

At a time when psychological discourse is often dominated by brain scans and biochemical imbalances, Adler’s emphasis on the subjective and interpersonal dimensions of experience serves as a reminder of the irreducible complexity and agency of the self. In a world of growing inequality, alienation, and polarization, Adler’s call for social interest and community feeling as the ultimate measure of mental health and human progress is more timely than ever.

As we grapple with the challenges of globalization, technological disruption, and ecological crisis, Adler’s vision of psychotherapy as a force for social transformation and human welfare takes on new urgency and relevance. His conception of the therapist as a collaborator, encourager, and fellow traveler on the path of life, rather than an expert analyst or healer of psychic wounds, offers a powerful model for a more democratic and empowering approach to mental health care.

In this sense, Adler’s legacy is not just a matter of historical interest but a living resource for the ongoing development of psychology and psychotherapy. By reconnecting with his pioneering insights and example, we can enrich our understanding of the human condition and expand our repertoire of creative responses to the challenges of our time.

This does not mean uncritically accepting all of Adler’s specific theories or techniques, some of which are bound to his cultural and historical context. Like all great thinkers, Adler was a product of his time and place, and his work reflects certain biases and blindspots that need to be acknowledged and transcended.

For example, Adler’s early adherence to a unitary “masculine protest” theory of neurosis, while an improvement over Freud’s libido theory, still reflects a limited and essentialist view of gender that is problematic from a contemporary perspective. Similarly, his emphasis on striving for superiority and perfection, while intended as a positive and growth-oriented concept, can sometimes veer into a kind of hyper-individualism that downplays the importance of acceptance, interdependence, and the tragic dimensions of existence.

Engaging Adler’s legacy critically and creatively means sifting through his complex body of work to find the gems that can illuminate our present situation, while also recognizing the historical and cultural limitations of his perspective. It means building on his core insights about the indivisible unity of the person, the creative power of the self, the compensatory function of the unconscious, and the social responsibility of psychology, while also integrating them with new developments and challenges in the field.

Adler’s Vision for Psychology and Humanity

At the heart of Adler’s individual psychology is a profound faith in the human potential for growth, creativity, and social contribution. For Adler, mental health is not just the absence of symptoms or the adjustment to social norms, but the positive presence of Gemeinschaftsgefühl – the feeling of being meaningfully connected to and actively engaged in the larger community of life.

In contrast to Freud’s “adaptation model” of psychotherapy, which aimed to help people better cope with the inevitable conflicts and repressions of society, Adler proposed an “empowerment model” that sought to awaken people to their creative capacities and social responsibilities. The goal of Adlerian therapy is not just to relieve suffering but to encourage full participation in the ongoing improvement of the human condition.

This vision of psychotherapy as a catalyst for individual and social transformation is rooted in Adler’s deep conviction that all human beings are inherently creative, purposeful, and meaning-seeking creatures. For Adler, we are not just passive products of biology and environment, but active co-creators of our lives and our world. Even our symptoms and setbacks, properly understood, can be seen as misguided attempts to find significance and belonging in difficult circumstances.

The task of psychology, in this light, is not just to study the mind or treat mental illness, but to nurture the fundamental human drive towards connection, contribution, and self-transcendence. It is to help people recognize and develop their innate capacities for courage, compassion, and cooperation in the face of life’s challenges and opportunities. In Adler’s famous phrase, psychotherapy is a process of “healing through meeting” – a collaborative dialogue that reveals our common struggles and potentials as fellow travelers in the journey of life.

This understanding of psychology as a socially embedded and culturally responsive discipline, oriented towards the holistic growth and empowerment of persons in community, stands in sharp contrast to the increasingly reductionistic, medicalized, and individualistic approaches that have dominated much of mainstream psychology in recent decades. Against the tide of biological determinism and pharmacological quick fixes, Adler’s vision reminds us of the irreducibly personal and interpersonal dimensions of mental health and well-being.

At a time when psychology is often seen as a narrow and specialized field, focused on fixing individual pathologies rather than understanding and transforming social systems, Adler’s example calls us back to the larger purposes and possibilities of the discipline. He challenges us to see psychology not just as a value-neutral science or a technical profession, but as a culturally situated and ethically engaged practice – a way of using our knowledge and skills to promote the greater good of humanity.

This means expanding our understanding of the “client” to include not just individuals, but families, communities, and society as a whole. It means recognizing the ways in which personal problems are often reflections of larger social and existential issues, requiring interventions at multiple levels. And it means using our psychological insights and tools to advocate for social justice, democratic participation, and the creation of a more nurturing and inclusive human world.

In this sense, Adler’s legacy is not just a historical artifact but a living challenge and inspiration for the future of psychology and psychotherapy. By reconnecting with his original vision and applying it creatively to the problems and possibilities of our time, we can help to build a more humane, responsive, and transformative approach to mental health and social change.

This is the unfinished business of Adler’s individual psychology – the ongoing task of realizing his dream of a psychology that honors the whole person in social context, that empowers individuals and communities to take responsibility for their lives and their world, and that works towards the goal of a more just, compassionate, and self-actualizing human future. As we stand at the crossroads of a new century, with all its perils and promises, this vision is more needed than ever.

May we have the wisdom and the courage to carry it forward, in theory and practice, for the sake of our shared humanity and our fragile planet. This is the enduring gift and challenge of Alfred Adler’s life and work.

Continued Education in Adlerian Psychology

General Overviews & Biographies

- Simply Psychology: Alfred Adler – This article offers a solid biography of Adler, along with an introduction to his key ideas such as inferiority complex, compensation, and his break from Freud.

- Alfred Adler Institute of Northwestern Washington – A comprehensive resource offering biographical details, Adler’s main works, and a detailed understanding of his psychological principles.

- Alfred Adler Biography – Encyclopedia Britannica – A well-rounded biographical overview covering Adler’s personal life, career, and contributions to psychology.

- History of Alfred Adler – Verywell Mind – A useful biography with an overview of Adler’s major concepts and influence in psychology.

- Alfred Adler: A Biography by Phyllis Bottome – A book-length biography of Adler written by one of his followers, offering detailed insights into his life and work.

Theories & Concepts

- Psychology Today: Adlerian Psychology – This article explains Adlerian psychology and how it differentiates itself from other schools of thought.

- Alfred Adler’s Individual Psychology – This article delves into Adler’s theory of individual psychology, including its emphasis on the importance of social interest, community feeling, and personal growth.

- Inferiority Complex: What it Means and How Adler Used It – A look into Adler’s famous concept of inferiority complex, which was central to his theories about human development and motivation.

- Psychology Fanatic: Individual Psychology – A detailed article on the fundamental principles of Adler’s Individual Psychology and how it is applied in therapy and personal development.

- Alfred Adler’s Theory on Birth Order – A summary of Adler’s theory on birth order and how it influences personality and behavior.

Books by Alfred Adler

- Understanding Human Nature – This book is one of Adler’s most popular works, offering a clear view of his approach to human psychology and behavior.

- What Life Could Mean to You – A classic text by Adler that discusses the role of personal responsibility, courage, and social interest in human life.

- The Science of Living – Adler’s exploration of human behavior, focusing on self-awareness, lifestyle, and the social structure that shapes personality.

- Superiority and Social Interest: A Collection of Adler’s Works – A collection of Adler’s writings that explore his key concepts like the striving for superiority, inferiority feelings, and social interest.

Articles & Papers

- Alfred Adler and the Birth of Individual Psychology (APA) – This article traces the development of Individual Psychology and Adler’s place in the history of psychotherapy.

- A Comparative Study of Freud and Adler’s Theories – An academic paper comparing the differing views of Freud and Adler, particularly on the role of the unconscious.

- Journal of Individual Psychology: History and Development – A peer-reviewed journal dedicated to Adlerian psychology, featuring academic papers on various aspects of his theories.

- Adler’s Concept of Social Interest – An academic article explaining the importance of “Gemeinschaftsgefühl” (community feeling) in Adler’s work, and how it plays into mental health and personal development.

- Alfred Adler’s Influence on Positive Psychology – An article on how Adler’s ideas, particularly his focus on optimism and social interest, influenced the development of Positive Psychology.

Adler’s Historical Influence

- Alfred Adler’s Break with Freud – An in-depth look at Adler’s break from Sigmund Freud and how his disagreements helped shape his own school of thought.

- Adler’s Role in the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society – An article detailing Adler’s early relationship with Freud and his role in the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society before they parted ways.

- Adler and the Founding of Individual Psychology – A detailed article tracing how Adler’s thinking evolved from psychoanalysis into a distinct psychological movement.

- Alfred Adler’s Legacy in Psychotherapy – A detailed overview of how Adler’s theories of personality, social influence, and individual development continue to influence modern psychotherapy.

Contemporary Applications of Adlerian Psychology

- How Adlerian Therapy is Used Today – An article on how Adlerian concepts are applied in modern therapeutic practices, particularly in family and individual therapy.

- Alfred Adler’s Work in Educational Psychology – A research paper on how Adler’s concepts have influenced educational practices and child development theories.

- Adlerian Therapy Techniques – A detailed guide on the practical application of Adlerian therapy, including strategies like encouragement, lifestyle assessment, and developing social interest.

- How Birth Order Impacts Children’s Personalities – An article discussing modern research on birth order, a concept initially developed by Alfred Adler.

Additional Resources

- The Adler Graduate School – An institution offering degree programs, certification, and resources based on Adler’s psychological principles.

- Adlerian Psychology on YouTube – A video explaining Adler’s core concepts, focusing on how his work is still relevant in psychology today.

- The Impact of Adler’s Ideas in Modern Coaching – A professional coaching article that discusses how Adler’s ideas about motivation and behavior are used in modern life coaching.

0 Comments