The Mystic of Paradox: Johannes Scheffler’s Transformation

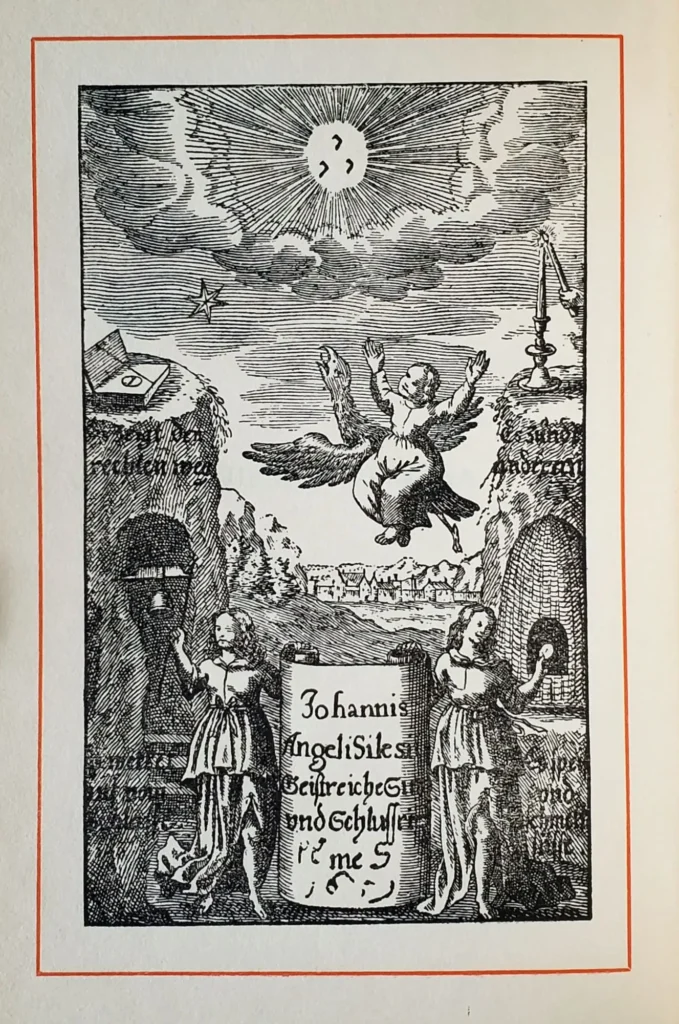

In the history of Christian mysticism, few figures are as polarizing and profound as Angelus Silesius. Born Johannes Scheffler in 1624, amidst the chaos of the Thirty Years’ War, he began his life as a Lutheran physician and ended it as a Catholic priest and poet whose couplets would challenge the boundaries of theology for centuries. His work, particularly The Cherubic Pilgrim, is not merely poetry; it is a psychological map of the soul’s ability to transcend the ego.

Silesius is a master of the “coincidentia oppositorum”—the coincidence of opposites. For the depth psychologist, his writings offer a pre-modern framework for understanding the tension of opposites that defines the human psyche. He forces us to confront the reality that the path to wholeness often requires a descent into “Divine Nothingness.”

Biography & Timeline: Angelus Silesius (1624–1677)

Johannes Scheffler was born in Breslau, Silesia (modern-day Wrocław, Poland). His life was marked by a relentless search for truth that led him across the rigid sectarian lines of his day. Disillusioned by the dogmatism of the Lutheran establishment, he turned inward, discovering the writings of earlier German mystics like Meister Eckhart and Jakob Böhme.

In 1653, he made the radical decision to convert to Catholicism, taking the name Angelus Silesius (“The Silesian Messenger”). This was not just a religious conversion but a psychological one—a movement from the “letter of the law” to the “spirit of the depths.”

Key Milestones in the Life of Angelus Silesius

| Year | Event / Publication |

| 1624 | Born in Breslau to a Lutheran noble family. |

| 1647 | Received his doctorate in philosophy and medicine from the University of Padua. |

| 1653 | Converted to Roman Catholicism, adopting the name Angelus Silesius. |

| 1657 | Published The Cherubic Pilgrim (Der Cherubinische Wandersmann), his masterpiece of mystical poetry. |

| 1661 | Ordained as a Catholic priest. |

| 1677 | Died at the age of 52, leaving a legacy that would influence Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and Jung. |

Major Concepts: The Psychology of the Ungrund

The God Within and the Ungrund

At the heart of Silesius’ thought is the concept of the Ungrund (the Abyss or Unground). Borrowing from Jakob Böhme, Silesius views God not as a “thing” or a “being” in the sky, but as the groundless ground of all existence. Psychologically, this mirrors the Unconscious—the vast, unknowable source from which the ego emerges.

Silesius writes: “God is a pure Nothing! Concealed in Now and Here: The less you reach for Him, the more He will appear.”

This is a radical statement of Apophatic Theology (Negative Theology). It suggests that to find the Self, one must stop “grasping” with the ego. In therapy, this aligns with the need to surrender the rigid control mechanisms of the conscious mind to allow healing to emerge from the unconscious.

The Birth of God in the Soul

Silesius posits that the human soul is the only place where God can become conscious of Himself. “I am as great as God, He is as small as I; He cannot be above me, nor I beneath Him lie.”

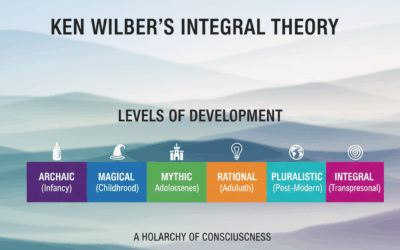

For Jung, this was a perfect description of the Ego-Self Axis. The “God” Silesius speaks of is the Archetype of Wholeness. The “birth of God” is the process of individuation—the realization that the little “I” is contained within a greater Subject.

The Conceptualization of Trauma: The Failure to Die

Silesius views spiritual/psychological suffering as a refusal to undergo the necessary “death” of the ego. His famous couplet states: “Die before you die, so that when you die, you will not die.”

The Trauma of Attachment

In his view, trauma persists because we cling to the “creature”—our finite, wounded identity. We say “I am a victim,” “I am abandoned.” Silesius argues that healing requires a radical self-annihilation (Entwerdung). This is not a physical death, but the death of the persona and the defense mechanisms that keep us trapped in the past.

This resonates with modern treatments for PTSD like Narrative Exposure Therapy or somatic work, where the patient must “release” the frozen energy of the trauma. The “old self” that was traumatized must be integrated so a “new self” can emerge.

Paradox as Therapeutic Tool

Silesius uses paradox to break the mind’s rigid categories. “The way to life is death, the way to rise is fall.”

In therapy, we often find that the “way up is down.” We must descend into the grief (the fall) to rise into resilience. By embracing the paradox, the patient moves from a black-and-white (splitting) worldview to a nuanced, integrated reality.

Lasting Influence: The Mystic as Psychologist

Angelus Silesius challenged the literalism of his day, just as depth psychology challenges the materialism of ours. His influence extends to philosophers like Heidegger and Wittgenstein, who saw in his poetry a way to speak about the unspeakable.

For the modern seeker or patient, Silesius offers a stark but hopeful truth: You are more than your history. There is a “Non-Being” within you—a spaciousness that trauma cannot touch. By learning to “un-become,” we create the space for true Being to shine through.

Further Reading & Resources

- Paulist Press: Angelus Silesius: The Cherubinic Wanderer.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Mysticism and Apophatic Theology.

- The Jung Page: Resources on Jung and the Mystical Tradition.

0 Comments