The Dark Mirror of the Soul: Exploring Southern Gothic through a Jungian Lens

In the humid, kudzu-draped landscapes of the American South, a literary tradition emerged that would plumb the depths of the human psyche like few others. Southern Gothic literature, with its haunting tales of decay, madness, and the supernatural, serves as a powerful lens through which we can examine the complexities of the human mind. From the perspective of Jungian psychology, these stories offer rich territory for exploring concepts like the Shadow, the Collective Unconscious, and the painful journey towards Individuation.

The genre does not merely tell ghost stories; it acts as a mechanism for a culture to process its repressed trauma. Just as a dream brings the subconscious to the surface, Southern Gothic literature brings the darker history of the South—its violence, its racism, its fallen aristocracy—into the light. For the residents of Birmingham, Alabama, this is not just fiction; it is the atmospheric pressure of our daily lives. The sweltering heat that presses down on the city often feels like a physical manifestation of the psychological pressure to maintain appearances while the past rots beneath the floorboards.

Birmingham: The Gothic Landscape of Iron and Ghosts

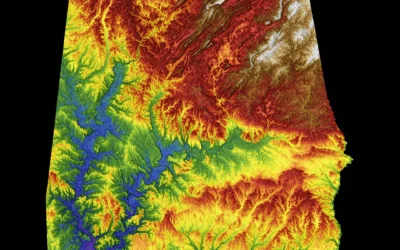

Birmingham, Alabama, nestled in the heart of the South, has profound connections to this literary tradition. While often overshadowed by the literary giants of Mississippi or Georgia, Birmingham’s history of racial tension, industrial boom and bust, and the lingering echoes of the Civil War provide fertile ground for Gothic themes. The city itself is a study in contrasts—the manicured lawns of Mountain Brook versus the industrial scars of North Birmingham—that mirrors the Jungian split between the Persona (the mask we wear) and the Shadow.

One cannot discuss the Gothic nature of Birmingham without mentioning Sloss Furnaces. Now a National Historic Landmark, this complex of blast furnaces produced iron for nearly a century. Today, it stands as a rusting, hulking skeleton against the skyline—a literal “dark factory” that Jung might interpret as a symbol of the transformative, alchemical fire of the psyche. Local folklore claims it is haunted by the ghost of “Slag” Wormwood, a cruel foreman. Psychologically, Sloss serves as a collective vessel for the city’s industrial trauma—a place where the brutal reality of labor and death is preserved in iron, much like a repressed memory.

Events like the Sidewalk Film Festival frequently showcase films that tap into this Southern grit and eccentricity, proving that the Gothic sensibility is alive and well in the Magic City. Furthermore, the Oak Hill Cemetery, the city’s oldest burial ground, rests on a hill overlooking the skyline, a permanent reminder of the ancestors watching over the living—a core tenet of the Jungian concept of the ancestral soul.

The Psychology of the Grotesque

To truly understand the psychological power of Southern Gothic, we must understand the function of the “grotesque.” In literary terms, a grotesque character is one who induces both empathy and disgust. In Jungian terms, the grotesque is a manifestation of the Shadow—those aspects of ourselves that we deny, repress, or hide because they do not fit our ideal self-image.

The South is a culture traditionally obsessed with manners, propriety, and the “Persona.” We say “bless your heart” when we mean something far darker. Because the Persona is so rigid and polite, the Shadow must compensate by becoming equally extreme. This is why Southern Gothic literature is filled with physical deformities, madness, and taboo violence. The repression of the “polite South” creates the monsters of the “Gothic South.”

Truman Capote: The Puer Aeternus and the Search for the Father

Truman Capote, born in New Orleans but spending much of his childhood in Monroeville, Alabama (just a few hours south of Birmingham), crafted stories that often dealt with themes of isolation and the struggle for identity. His novella Other Voices, Other Rooms is a prime example of how Southern Gothic can serve as a vehicle for exploring Jungian concepts.

The protagonist, Joel Knox, acts as an archetype of the Puer Aeternus (the eternal boy), a child who cannot grow up because he is trapped in a world of mother-complexes and absent fathers. Joel embarks on a journey to find his father, which can be read as a metaphor for the quest to understand one’s own Animus (the male aspect of the soul). The strange and often grotesque characters Joel encounters—like the transgressive Cousin Randolph—are not just neighbors; they are projections of Joel’s own fractured psyche.

Capote’s decrepit Skully’s Landing serves as a physical manifestation of the unconscious mind—overgrown, decaying, and isolating. Joel’s journey through this landscape is a confrontation with the parts of himself he has yet to integrate. In therapy, we often see clients who are “stuck” at Skully’s Landing, trapped in a childhood trauma that prevents them from entering the adult world.

Flannery O’Connor: Violence as a Path to Grace

Flannery O’Connor, perhaps the most renowned Southern Gothic author, takes the exploration of the Shadow to violent extremes. A devout Catholic, O’Connor believed that the modern world was so numb that it required something shocking—something grotesque—to wake it up to spiritual reality.

In her famous story “Good Country People,” the character of Hulga represents the Hyper-Rational Ego. With her wooden leg and Ph.D. in philosophy, she believes she is intellectually superior to the “simple” folk around her. She represents the intellect divorced from the body and spirit. Her encounter with the Bible salesman—a Trickster figure—who steals her prosthetic leg is a brutal confrontation with the Shadow. He strips her of her primary defense mechanism (her intellect and her physical crutch), leaving her vulnerable. In Jungian therapy, this is the moment of “collapse” that often precedes a breakthrough.

In “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” the character of The Misfit serves as a dark agent of transformation. He is the Shadow personified—amoral, violent, and chaotic. Yet, it is only when facing him that the Grandmother loses her superficial Southern manners and touches true grace. O’Connor famously wrote, “I use the grotesque the way you use a telescope to see something far away.” Psychologically, she uses the grotesque to force the ego to confront the neurobiology of shame and the reality of the self.

William Faulkner: The Burden of the Collective Unconscious

No discussion of Southern psychology is complete without William Faulkner. His fictional Yoknapatawpha County is essentially a map of the Southern Collective Unconscious. Faulkner famously wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” This is a perfect summary of how intergenerational trauma works.

In works like The Sound and the Fury or Absalom, Absalom!, characters are not just fighting their own battles; they are fighting the ghosts of their ancestors. The sins of the fathers (slavery, war, illegitimacy) infect the children. In Birmingham, we see this daily. The history of the Civil Rights movement, the bombings of the 1960s, and the economic segregation of the city are “ghosts” that sit in the therapy room with us. Faulkner teaches us that we cannot be healthy individuals until we integrate the shadow of our history.

In Jungian terms, Faulkner’s characters are often possessed by “complexes”—autonomous personalities formed by trauma that override the conscious will. The decline of the Compson family mirrors the decline of the Southern Aristocracy archetype, a necessary death for the emergence of a new, more integrated South.

Modern Echoes: From Harper Lee to S-Town

The tradition continues. Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird offers a “Daylight Gothic,” where the monster is not a ghost but the systemic racism of a small town. Boo Radley serves as the classic Shadow figure—fearful and rumored to be a monster, but ultimately revealed to be a protector. This integration of the “monster” is the ultimate goal of Jungian Shadow Work.

More recently, the hit podcast S-Town, centered on Woodstock, Alabama (a short drive from Birmingham), brought the Southern Gothic into the 21st century. The protagonist, John B. McLemore, is a classic Gothic figure: a brilliant clockmaker living in a hedge maze, obsessed with the decay of the world. His story explores the intersection of genius, madness, and the crushing weight of isolation in the rural South.

Birmingham’s own Gin Phillips, in her novel Come In and Cover Me, uses ghostly visitations as a means of exploring memory, grief, and self-discovery. The protagonist’s archaeological work serves as a metaphor for digging into the layers of the psyche, unearthing buried truths and confronting the shadows of the past. Local bookstores like The Alabama Booksmith in Homewood champion these local voices, keeping the tradition of introspection alive.

The Archetypal Function of the Gothic Landscape

The power of Southern Gothic literature lies in its ability to externalize internal psychological states. The decaying mansions, overgrown gardens, and oppressive heat serve as physical manifestations of psychological conditions. When a character in a Faulkner novel is trapped in a rotting house, it is a symbol that they are trapped in a neurotic complex. The kudzu that swallows telephone poles in Alabama is a symbol of the unconscious swallowing the conscious mind.

This externalization allows readers to confront difficult truths about themselves in a way that might be too threatening if approached directly. It provides a container for the horror of trauma. In therapy, we often use similar techniques—metaphor, art, and dream analysis—to help clients look at their trauma indirectly before they are ready to face it head-on.

The mystical elements common in Southern Gothic literature align well with Jung’s interest in the numinous and transcendent aspects of the psyche. The genre’s frequent use of religious imagery—preachers, prophets, baptisms in muddy rivers—speaks to the human need for meaning beyond the material world. This is particularly relevant in Birmingham, part of the Bible Belt, where religious faith is a dominant archetype that can be both a source of healing and a source of religious trauma.

Finding the Gold in the Shadow

It’s worth noting that while Southern Gothic literature often deals with dark and disturbing themes, it is not without hope. The genre’s use of humor, albeit often dark, serves as a means of confronting difficult truths. This aligns with Jung’s belief in the importance of accepting all aspects of oneself, including the shadow, as a path to wholeness.

As we walk the streets of Birmingham, from the cobblestones of Morris Avenue to the trails of Red Mountain Park, we might consider how the city’s own history of struggle and renewal reflects the transformative journeys found in Southern Gothic literature. The genre reminds us that growth often comes through confronting our shadows, and that even in the most unlikely places—be it a decaying Southern mansion or a former industrial city—we can find the path to our true selves.

In the end, Southern Gothic literature, like Jungian psychology, invites us to embrace the fullness of human experience—the beautiful and the grotesque, the rational and the mystical, the conscious and the unconscious. It is a tradition that continues to resonate, offering insight and catharsis to those willing to venture into its shadowy, kudzu-covered realms.

Bibliography:

- Bloom, H. (2009). Flannery O’Connor (Bloom’s Modern Critical Views). Infobase Publishing.

- Capote, T. (1948). Other Voices, Other Rooms. Random House.

- Carpenter, B. (2013). “Splendid Failure”: Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Humanities, 2(4), 756-782.

- Ciuba, G. M. (2007). Desire, Violence & Divinity in Modern Southern Fiction: Katherine Anne Porter, Flannery O’Connor, Cormac McCarthy. LSU Press.

- Faulkner, W. (1929). The Sound and the Fury. Jonathan Cape & Harrison Smith.

- Fowler, D. (1997). Faulkner: The Return of the Repressed. University of Virginia Press.

- Gentry, M. B. (1986). Flannery O’Connor’s Religion of the Grotesque. Univ. Press of Mississippi.

- Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and His Symbols. Doubleday.

- Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological Types (Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 6). Princeton University Press.

- McCullers, C. (1940). The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. Houghton Mifflin.

- O’Connor, F. (1955). A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

- Phillips, G. (2012). Come In and Cover Me. Riverhead Books.

- Proehl, K. B. (2019). Queer Gothic Literature: An Annotated Bibliography. McFarland.

- Rubin, L. D. (1985). The History of Southern Literature. LSU Press.

- Skei, H. H. (1999). Reading Faulkner’s Best Short Stories. University of South Carolina Press.

- Stein, M. (1998). Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Open Court.

- Todorov, T. (1975). The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. Cornell University Press.

- Yaeger, P. (2000). Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women’s Writing, 1930-1990. University of Chicago Press.

- Young-Eisendrath, P., & Dawson, T. (Eds.). (2008). The Cambridge Companion to Jung. Cambridge University Press.

- Zimmerman, B. (1999). The Safe Sea of Women: Lesbian Fiction 1969-1989. Beacon Press.

Birmingham Arts and Culture

0 Comments