Highway 280: The Psychological Bypass How Birmingham’s Suburbs Built Infrastructure to Avoid the City

Every day, thousands of people commute along Highway 280, connecting Vestavia Hills to Mountain Brook to Homewood to Inverness to Greystone. It’s congested, sprawling, lined with strip malls and office parks. Most people assume it developed organically, following natural growth patterns.

It didn’t.

Highway 280 was built with a specific psychological purpose: to allow suburban residents to live, work, shop, and socialize without ever entering Birmingham proper. It’s not a road to the city. It’s a road around the city. And as a social worker working in these communities, I find the mental health implications of this “bypass psychology” both fascinating and troubling.

The Origin Story Nobody Talks About

Highway 280 was conceived in the late 1960s and built primarily in the 1970s. This timing isn’t coincidental.

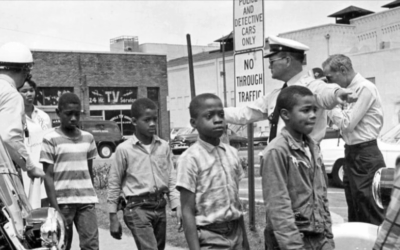

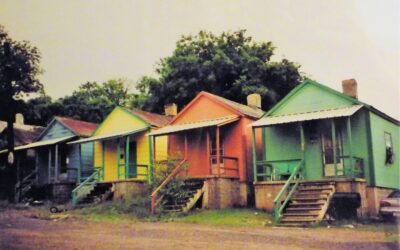

The 1960s saw Birmingham become internationally infamous for racial violence—police dogs and fire hoses in Kelly Ingram Park, the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, brutal resistance to integration. The city’s image was devastated. White residents, particularly those with means, accelerated their move “over the mountain” to suburbs like Vestavia Hills, Mountain Brook, and Homewood.

But there was a problem: these suburbs still depended on Birmingham for work, shopping, and services. Commuting required driving through the city, maintaining economic and psychological connection to the place they were fleeing.

Highway 280 solved this problem. It created an alternate geography where suburban residents could access each other’s communities, commute to suburban office parks, and shop at suburban retail—all while avoiding Birmingham entirely.

This wasn’t an accident. It was the point.

The Architecture of Avoidance

Urban planners and New Urbanist thinkers like Leon Krier, whom we’ve interviewed on our podcast, describe this phenomenon with brutal clarity: highways don’t just connect places; they reveal what we’re trying to avoid.

The Interstate Highway System famously destroyed urban neighborhoods—often Black neighborhoods—in cities across America. But Highway 280 does something different and arguably more psychologically revealing: it doesn’t go through Birmingham. It goes around Birmingham.

Look at a map. Highway 280 arcs from Childersburg through the mountain suburbs and connects to I-459, which itself is a bypass loop around Birmingham. You can live in Inverness, work in Vestavia, shop in Mountain Brook, and never cross into Birmingham’s city limits.

This is avoidance infrastructure. And it shapes not just traffic patterns but psychological patterns: what we learn to see, what we learn to ignore, and ultimately, who we consider part of “our” community.

The Psychology of Bypass Mentality

Here’s what happens psychologically when you can completely avoid a city you technically live adjacent to:

Out of Sight, Out of Mind: When you never drive through Birmingham’s neighborhoods, never shop in Birmingham’s stores, never eat in Birmingham’s restaurants, the city becomes abstract. Poverty, segregation, municipal challenges—they’re not your daily reality. They’re something you hear about on the news, not something you encounter.

Geographic Gatekeeping: Highway 280 creates what geographers call a “edge city”—a suburban zone that functions as if it’s independent from the urban core. Residents can convince themselves they’re not “Birmingham people.” They’re “280 corridor people” or “over the mountain people.” The psychological separation follows the geographic separation.

Taxation Without Participation: Many people who work and shop along 280 live in bedroom communities that contribute nothing to Birmingham’s tax base while depending on Birmingham for their prosperity. This creates a specific kind of civic disengagement: you benefit from proximity to a city while psychologically and financially distancing yourself from it.

The Illusion of Self-Sufficiency: When all your needs can be met within the 280 corridor, it’s easy to forget that this infrastructure, these suburbs, this entire system exists because of Birmingham—because of the city’s industrial wealth, because of its location, because of what it built. The bypass creates an illusion that the suburbs are independent entities rather than parasitic (or at least dependent) on the urban core.

What Leon Krier Would Say

In our podcast conversation, Leon Krier talked about how car-dependent infrastructure doesn’t just facilitate travel—it shapes consciousness. When your daily geography is limited to highways and parking lots, when you go from private space (home) to private vehicle (car) to private space (office/store), you never navigate shared public space.

You never encounter the full diversity of your region. You never have to negotiate difference. You never develop what political theorists call “civic capacity”—the ability to see yourself as part of a broader community with shared interests and shared responsibility.

Highway 280 epitomizes this problem. It’s not a street where you might encounter your neighbors. It’s not a boulevard with sidewalks and mixed use. It’s a high-speed corridor designed explicitly to help you avoid encounter. You’re not part of a community traveling together. You’re isolated in your vehicle, focused on your destination, psychologically separated from everyone and everything you’re passing.

And when this is your daily experience of place, it shapes how you think about community, responsibility, and belonging.

The Therapeutic Consequences of Geographic Avoidance

In my practice, I see how this bypass mentality manifests in individual psychology:

Adolescents and Young Adults: Many grew up never visiting Birmingham, never developing any connection to the urban core their grandparents or great-grandparents might have worked in or lived near. They identify exclusively with their suburb. This creates a strange provinciality—they live in a major metropolitan area but have the psychological geography of a small town. When they eventually encounter urban poverty, racial diversity, or municipal challenges, they lack context. It feels foreign, frightening, not their concern.

Parents: Often struggle with how to talk to their children about Birmingham, about race, about inequality. They’ve built their lives along 280 specifically to avoid these conversations, to create a sanitized environment. But avoidance isn’t preparation, and eventually reality intrudes. The result is often anxiety, defensiveness, and a doubling-down on geographic separation as the solution.

Older Adults: Particularly those who remember Birmingham before the bypass, sometimes express a vague sense of loss or guilt. They remember when downtown Birmingham was vibrant, when they shopped at Pizitz and Loveman’s, when Birmingham felt like the center of their world. Now it feels abandoned, forgotten. Some recognize their role in that abandonment. Others justify it: “the city changed,” “it wasn’t safe,” “I had to think of my family.” Both responses carry psychological weight—unprocessed guilt or defensive rationalization.

The Racial Subtext Nobody Mentions

Let’s be direct: Highway 280 was built during white flight. The timing isn’t coincidental. The route isn’t coincidental. The function isn’t coincidental.

This doesn’t mean everyone who lives or works along 280 is racist. But it does mean the infrastructure itself carries the history of racial segregation and avoidance. And when we use infrastructure designed for avoidance, when we benefit from systems built explicitly to maintain separation, we inherit the psychological consequences of those choices—whether we consciously endorse them or not.

New Urbanists point out that segregation doesn’t require individual prejudice when the infrastructure does the work for you. If you’ve designed your daily geography so you never encounter the city’s Black neighborhoods, never shop in Black-owned businesses, never eat in Black-owned restaurants, never visit Black churches or schools—you’ve achieved effective segregation without ever expressing an explicitly racist thought.

Highway 280 facilitates this kind of structural racism. It allows people to live in a bubble of similarity while believing they’re “not racist” because they never actively discriminate. But avoidance is its own form of discrimination. Geographic separation is psychological separation.

The Myth of Suburban Independence

Here’s what the bypass psychology sells: your suburb is self-sufficient. You don’t need Birmingham. You have everything right here along 280—shopping, dining, offices, services.

But this is fantasy economics and fantasy psychology.

Every suburb along 280 depends on Birmingham for:

- Infrastructure: Water, sewage, power—often provided or subsidized by systems Birmingham built.

- Labor: Many people who work in Mountain Brook, Vestavia, and 280 corridor businesses live in Birmingham because they can’t afford suburban housing.

- Regional Identity: The suburbs exist because Birmingham created the wealth and infrastructure that made suburban development possible.

Psychologically, this creates what we might call “unacknowledged dependence”—benefiting from something you’re actively distancing yourself from. And unacknowledged dependence breeds resentment (toward the thing you depend on) and contempt (toward those who can’t hide their dependence as well as you can).

When Roads Reveal Values

Infrastructure isn’t neutral. The roads we build, the routes we prioritize, the connections we make and avoid—these are expressions of collective values and psychology.

Highway 280 says: We value separation over integration. We value convenience over encounter. We value the ability to avoid over the necessity to engage.

And for decades, that worked. The 280 corridor boomed. Development followed the highway. Office parks, shopping centers, new subdivisions—all built on the assumption that suburban residents wanted to avoid Birmingham and would pay a premium for the convenience of doing so.

But there are costs to this model that we’re only beginning to calculate:

Economic Cost: Birmingham’s tax base eroded as wealth moved to suburbs that don’t contribute to city finances. The city that created regional prosperity can’t maintain its infrastructure.

Social Cost: Geographic segregation reinforces social segregation. Suburbs along 280 remain overwhelmingly white while Birmingham itself is majority Black. This isn’t accidental—it’s architectural.

Psychological Cost: Residents of 280 corridor suburbs often express vague anxiety about Birmingham—fear of crime, fear of “going downtown,” fear of encountering difference. But fear breeds from unfamiliarity, and unfamiliarity is what the bypass was designed to create.

The New Urbanist Alternative

Leon Krier and other New Urbanists argue that healthy regions require what they call “transect planning”—a gradual integration of urban, suburban, and rural zones rather than hard boundaries. You shouldn’t be able to completely avoid the urban core because the core is what gives the region meaning, identity, and economic vitality.

But Highway 280 does the opposite. It creates hard separation—psychological and geographic. And that separation makes regional cooperation nearly impossible.

Compare this to cities that integrated their infrastructure intentionally:

- Portland’s MAX light rail connects suburbs to downtown, creating shared transit experience

- Minneapolis’s connected street grid makes avoiding the city geographically difficult

- Charleston’s historic preservation kept downtown vital, preventing suburban flight

Birmingham built the opposite: infrastructure designed explicitly for avoidance. And we’re living with the consequences.

What This Means for Mental Health and Community

When clients come to me from Vestavia, Mountain Brook, Homewood, or communities along 280, they often describe a specific kind of malaise: disconnection from anything larger than their immediate bubble.

They live in nice houses, safe neighborhoods, good school districts. But they feel unmoored, like they’re not part of anything real or significant. They’ve optimized for comfort and safety but lost a sense of place, of civic identity, of belonging to something complex and challenging and alive.

This isn’t just individual psychology. It’s the psychological consequence of bypass infrastructure. When you can avoid your region’s challenges, when you never have to encounter its full diversity, when your daily geography is limited to a sanitized corridor—you lose the friction that creates meaning.

Psychologically, we need challenge. We need encounter. We need to navigate spaces we can’t fully control. Highway 280’s promise was freedom from friction. But friction is what keeps us engaged, what forces growth, what creates genuine community rather than comfortable isolation.

Breaking the Bypass Mentality

The good news: infrastructure doesn’t have to determine consciousness. You can use Highway 280 without adopting bypass psychology.

Intentional Encounter: Make deliberate trips into Birmingham. Support downtown businesses, attend events in city neighborhoods, eat at restaurants you wouldn’t encounter on 280. It’s not about charity—it’s about expanding your geographic and psychological map of where you live.

Civic Engagement: Recognize that regional prosperity requires regional thinking. If you work along 280 but live in a suburb, you’re still part of Birmingham’s economic ecosystem. Act like it. Support regional transit. Advocate for policies that benefit the whole area, not just your suburb.

Honest Conversation: Talk openly with your family, especially children, about why Highway 280 exists, what it was designed to accomplish, and what the costs of that design have been. Don’t sanitize the history. Suburban comfort came at a cost to the urban core, and pretending otherwise is psychologically corrosive.

Challenge Geographic Identity: When people ask where you’re from, don’t say “I’m not from Birmingham, I’m from Vestavia/Mountain Brook/Homewood.” Say “I’m from the Birmingham area” or “I live in Birmingham’s suburbs.” Small linguistic choices reflect and shape how you think about community and belonging.

You live in a region, not just a corridor. And regions only thrive when residents take psychological ownership of the whole, not just the comfortable parts.

The Broader Pattern

Highway 280 isn’t unique. Every major American city has bypass infrastructure built during white flight:

- Atlanta’s I-285 “perimeter”

- Washington DC’s I-495 “beltway”

- Houston’s Loop 610

These highways reveal a national pattern: wealth flees to suburbs, then builds infrastructure to avoid returning to the cities that created that wealth.

But increasingly, this model is failing. Suburbs are aging, infrastructure is crumbling, and younger generations are rejecting car-dependent sprawl in favor of walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods—often in the urban cores their parents fled.

Birmingham faces a choice: continue building for avoidance, or begin retrofitting for connection.

When Geography Is Psychology

As a therapist working in Birmingham’s suburbs, I’ve learned that place shapes consciousness in ways we rarely acknowledge. Highway 280 isn’t just a route—it’s a daily practice of avoidance that becomes habitual, unconscious, normalized.

You drive it without thinking. You navigate the sprawl without questioning why it exists. You live in the bubble without recognizing it’s a bubble.

But awareness changes everything. When you understand that your daily route was designed to help you avoid Birmingham, you can choose differently. You can use the highway without adopting the psychology it was built to create.

Robert Jemison built Mountain Brook without sidewalks because he thought cars made walking obsolete. Highway 280 was built without connection to Birmingham because planners thought suburbs could exist independently of cities.

Both were wrong. And decades later, we’re still living with the psychological consequences: isolation, disconnection, and the illusion that we can prosper by avoiding rather than engaging with the full complexity of our region.

The roads we build reveal who we are. Highway 280 reveals a community that chose separation over integration, convenience over encounter, comfort over challenge.

But roads can be rebuilt. And psychology can be changed. The bypass mentality isn’t inevitable—it’s a choice we make every time we get in the car.

If you’re struggling with questions of belonging, community, or feeling disconnected from anything larger than your immediate environment, therapy can help. Sometimes recognizing that your geographic habits reflect deeper psychological patterns is the first step toward change. Contact me to discuss how individual therapy can help you develop a more integrated sense of place, identity, and regional belonging.

0 Comments