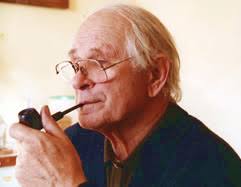

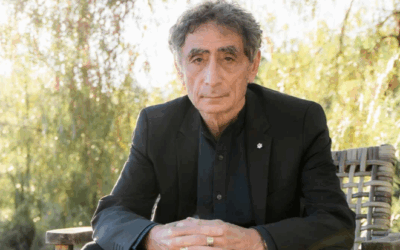

The Architect of the Developmental School

In the world of analytical psychology, Michael Fordham (1905–1995) is the figure who dared to bring Carl Jung down from the mythic clouds and into the nursery. While the classical school in Zurich focused on alchemy, adult individuation, and the collective unconscious, Fordham asked a practical, burning question: How does the Self manifest in an infant?

Fordham is the father of the “Developmental School” of Jungian analysis. He bridged the gap between Jung’s archetypal theories and the object-relations theories of British psychoanalysts like Donald Winnicott and Melanie Klein. His work fundamentally altered how we understand childhood, arguing that the infant is not just a “primitive” state of unconsciousness, but a complete human being with a functioning Self from birth.

Biography & Timeline: Michael Fordham

Born in Kensington, London, Fordham trained as a doctor at Cambridge and St Bartholomew’s Hospital. His early interest was in neurology, but he soon realized that the physical brain could not explain the complexities of the mind. He began analysis with a Jungian in 1933 and met Jung himself shortly after. They developed a close, albeit sometimes contentious, relationship.

Fordham was a driving force in professionalizing Jungian analysis in the UK. He co-founded the Society of Analytical Psychology (SAP) in 1946 and served as the editor of the English edition of Jung’s Collected Works. Unlike many Jungians who treated Jung’s word as gospel, Fordham was an empiricist; if Jung’s theory didn’t match the clinical data (especially with children), Fordham rewrote the theory.

Key Milestones in the Life of Michael Fordham

| Year | Event / Publication |

| 1905 | Born in Kensington, London. |

| 1933 | Begins analysis and meets C.G. Jung. |

| 1946 | Co-founds the Society of Analytical Psychology (SAP). |

| 1957 | Publishes New Developments in Analytical Psychology. |

| 1969 | Publishes Children as Individuals, challenging classical Jungian views on childhood. |

| 1976 | Publishes The Self and Autism, a groundbreaking study on the defenses of the early self. |

| 1995 | Dies in London, leaving behind a thriving developmental school. |

Major Concepts: The Primary Self and De-integration

The Primary Self vs. The Uroboros

The classical view, championed by Erich Neumann, held that the infant exists in a state of “Uroboric identity”—a blissful, unconscious fusion with the mother. Fordham rejected this. Based on his observations of infants, he argued for the Primary Self.

He believed that the Self (the archetype of wholeness) is present at birth. The infant is not a blank slate or a fragment of the mother; they are a whole person with their own archetypal potential waiting to unfold.

De-integration and Re-integration

If the Self is whole at birth, how do we interact with the world? Fordham proposed a rhythmic cycle:

- De-integration: The Self “unpacks” a part of itself to meet the environment. For example, the “hunger” drive de-integrates to seek the breast.

- Re-integration: After the experience (feeding), the energy returns to the Self, enriching it with memory and structure.

This pulsation is the heartbeat of psychic growth. Trauma occurs when this rhythm is disrupted—when the environment (Mother) fails to meet the de-integrating self, leaving the infant’s energy hanging in a void.

The Conceptualization of Trauma: Defenses of the Self

Fordham’s most profound clinical contribution was his understanding of early trauma and autism. He argued that when the environment is too hostile or chaotic, the infant’s Self cannot de-integrate safely.

The Defenses of the Self

To survive, the psyche creates rigid barriers. In his book The Self and Autism, Fordham described how the Self can turn inward, creating an impenetrable shell to preserve its core. In therapy, this manifests as a patient who is “unreachable” or who treats the therapist as an object rather than a person.

Clinical Implication: Healing requires the therapist to endure this rejection and slowly create a holding environment safe enough for the patient to risk de-integration again. This mirrors the temenos or sacred space required in all depth work.

Syntonic Countertransference

Fordham revolutionized how analysts use their own feelings. He distinguished between “illusory countertransference” (the analyst’s own baggage) and syntonic countertransference.

Definition: The analyst feels in their own body what the patient cannot yet feel. If the patient is dissociated from their rage, the analyst might feel a sudden, inexplicable anger. Fordham taught that this is not a mistake; it is an organ of perception. The analyst “metabolizes” this affect for the patient.

Legacy: The Developmental School

Michael Fordham split the Jungian world, but in doing so, he saved it from irrelevance. By integrating Jung with developmental science, he made Analytical Psychology a viable treatment for severe personality disorders, childhood trauma, and psychosis—conditions that classical analysis often avoided.

His legacy lives on in the “London School” of Jungian analysis, which emphasizes the analysis of the transference, the importance of infancy, and the rigorous study of the clinical interaction. He taught us that individuation does not begin at 40; it begins at the first breath.

Bibliography

- Fordham, M. (1957). New Developments in Analytical Psychology. Routledge.

- Fordham, M. (1969). Children as Individuals. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Fordham, M. (1976). The Self and Autism. Karnac Books.

- Fordham, M. (1985). Explorations into the Self. Academic Press.

- Fordham, M. (1993). The Making of an Analyst: A Memoir. Free Association Books.

0 Comments