In the early 1970s, while working as a technician and yoga instructor at a short-term psychiatric hospital, a young Pat Ogden noticed something her clinical training had not prepared her to see. Her patients exhibited a profound disconnection from their bodies, observable in their physical patterns, postures, and movements. More striking still, these somatic presentations seemed to correlate directly with their psychological difficulties in ways conventional talk therapy could not address. Before posttraumatic stress disorder even existed as a diagnostic category in the DSM, Ogden recognized that many patients were trapped in cycles of reliving the past, and that standard treatment methods only triggered traumatic reminders rather than resolving them.

This observation, born from direct clinical encounter rather than theoretical speculation, would eventually revolutionize trauma treatment. Ogden spent the next five decades developing Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, a comprehensive method that treats the body itself as the entry point for processing trauma rather than as a peripheral consideration. Her work demonstrated that traumatic memories encode not just in narrative and emotion but in physical patterns, defensive postures, arrested movements, and autonomic states that persist decades after the original events. These somatic imprints operate beneath conscious awareness, driving symptoms that resist cognitive intervention precisely because they never entered verbal-semantic memory systems.

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy integrates insights from attachment theory, neuroscience, cognitive approaches, somatic therapies, and the Hakomi Method into a phase-oriented treatment model specifically designed for trauma and developmental wounds. The approach has gained international recognition, influencing how thousands of therapists worldwide understand and treat complex trauma. Ogden’s foundational texts, published in the Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology alongside works by Daniel Siegel, Allan Schore, and Bessel van der Kolk, have become required reading for clinicians seeking to move beyond purely verbal approaches to healing.

Biographical information about Ogden’s early life remains relatively sparse in public sources, consistent with her emphasis on clinical practice and training over self-promotion. What is documented is that her interest in the mind-body connection emerged during her work as both a technician and yoga/dance teacher in psychiatric settings during the early 1970s. This dual role proved fortuitous. As a yoga and dance instructor, she observed how movement, breath, and embodied awareness affected emotional states. As a clinical technician, she witnessed how psychological disturbance manifested in bodily disconnection, chronic tension, restricted breathing, and defensive postural patterns.

The correlation between these observations suggested something conventional psychotherapy was missing. Patients could discuss traumatic events extensively without experiencing relief because the discussion occurred primarily in left-hemisphere verbal-cognitive systems while the trauma remained encoded in right-hemisphere somatic-emotional networks. Talk therapy activated thinking brain regions but left untouched the subcortical defensive systems where traumatic activation persisted. Ogden intuited that healing required engaging the body directly, accessing the implicit procedural memory systems where trauma actually lived.

In the early 1970s, Ogden began apprenticing with Ron Kurtz, who was developing what would become the Hakomi Method. Kurtz, trained in experimental psychology with deep interests in systems theory, Buddhism, Taoism, and somatic approaches, created a mindfulness-based, body-centered psychotherapy that would profoundly influence Ogden’s work. She was certified in Hakomi before any formal trainings existed at the institute, learning directly from Kurtz through intensive apprenticeship.

As Educational Director at Hakomi, Ogden designed the original curriculum in its entirety, establishing the pedagogical structure through which thousands of therapists would later train. She co-taught the very first Hakomi training alongside Kurtz in the late 1970s and was the first person to be certified in the method. This early involvement positioned her at the creative center of the emerging somatic psychology movement, working directly with Kurtz to translate intuitive clinical artistry into teachable principles and techniques.

In 1981, Ogden co-founded the Hakomi Institute with Kurtz and a core group including Dyrian Benz, Jon Eisman, Greg Johanson, Phil Del Prince, and Devi Records. However, Ogden’s particular interest in trauma, movement, and the treatment of sexual abuse survivors led her to pursue a specialized direction. With Kurtz’s blessing and support, she founded her own school in 1981, initially named Hakomi Bodywork and later Hakomi Integrative Somatics. This became what is today the Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute.

The split was amicable and collaborative rather than competitive. Kurtz named Ogden a Legacy Holder for the Hakomi Education Network, recognizing her foundational contributions. The two remained close friends and colleagues from the early 1970s until Kurtz’s passing in 2011, with each developing complementary approaches within the broader somatic psychology field. Hakomi emphasized present-moment mindfulness and the study of how experience organizes itself, while Sensorimotor Psychotherapy focused specifically on trauma treatment and the processing of overwhelming experience encoded somatically.

Ogden also served on the faculty at Naropa University from 1985 to 2005, bringing somatic approaches into academic psychology training. Naropa, founded by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche as the first Buddhist-inspired university in North America, provided ideal context for developing mindfulness-based therapeutic approaches. The contemplative emphasis aligned perfectly with Sensorimotor Psychotherapy’s use of present-moment awareness to track and transform habitual patterns.

The theoretical foundations of Sensorimotor Psychotherapy draw from multiple streams. From attachment theory, particularly the work of John Bowlby and Mary Main, Ogden incorporated understanding of how early relational trauma shapes capacity for self-regulation and interpersonal connection. Insecure attachment produces not just psychological insecurity but specific somatic patterns, ways of holding the body that reflect internal working models of relationship.

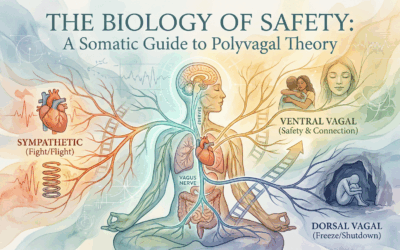

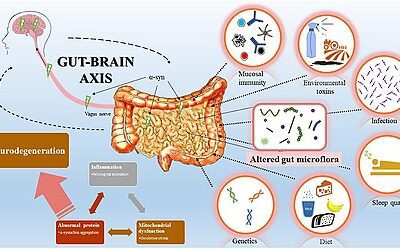

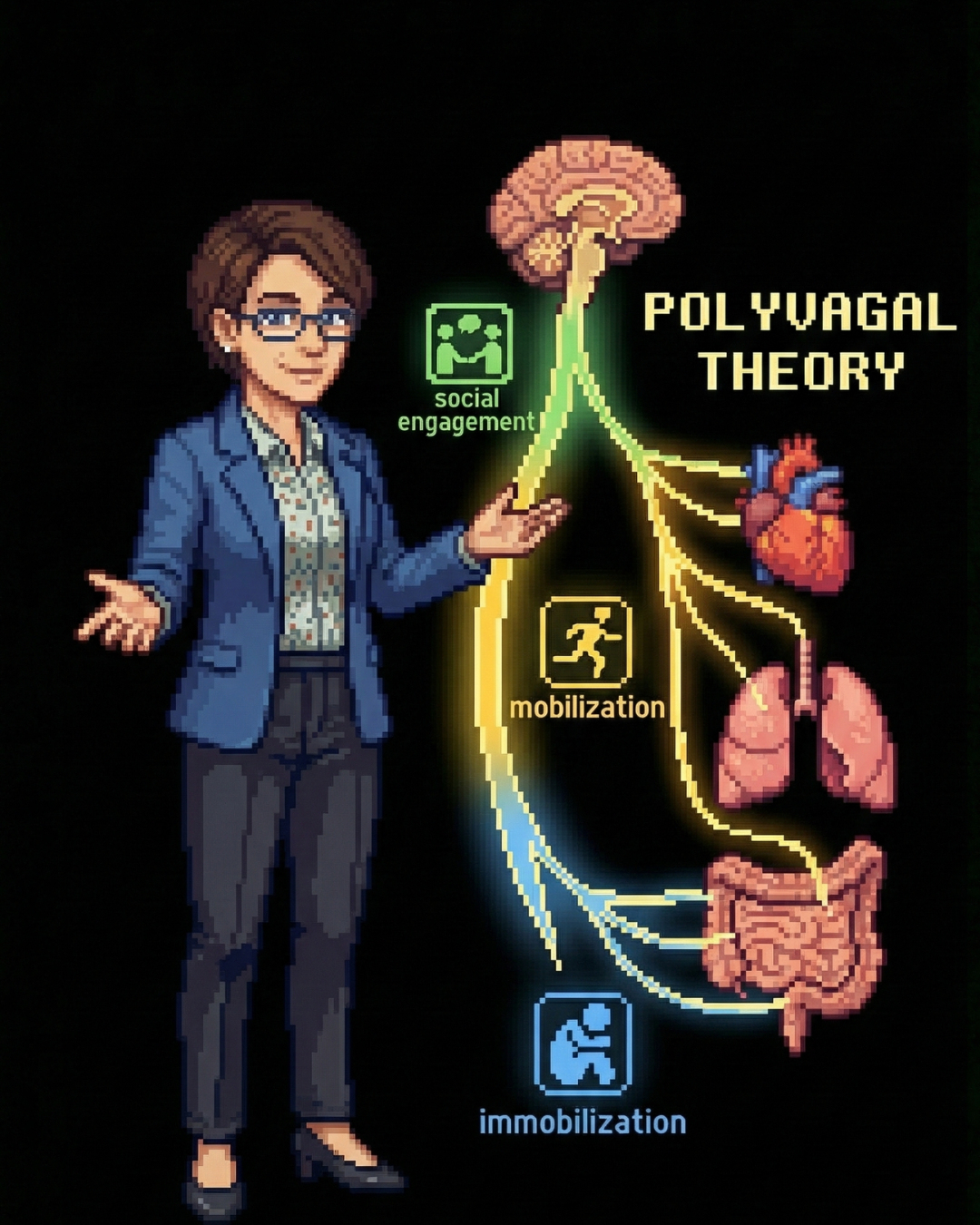

From neuroscience, particularly Allan Schore’s work on right brain development and affect regulation, Ogden grounded her observations in understanding of how trauma affects neural architecture. The right hemisphere, dominant for processing emotional and somatic information, develops through early attachment relationships. When these relationships involve trauma or chronic misattunement, right brain systems that should regulate arousal and emotion instead perpetuate dysregulation. Stephen Porges’s polyvagal theory, which Ogden integrates extensively, provides framework for understanding how autonomic states shift between ventral vagal social engagement, sympathetic mobilization, and dorsal vagal shutdown.

From Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing, Ogden adopted recognition that trauma involves incomplete defensive responses, movements toward fight or flight that were interrupted and never discharged. These arrested actions remain active in the nervous system as chronic tension, hypervigilance, or collapse. Healing requires completing these defensive sequences in safe therapeutic context, allowing the body to finish what it started when overwhelmed.

From research on dissociation and structural dissociation, particularly the work of Onno van der Hart, Ellert Nijenhuis, and Janina Fisher, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy incorporates understanding that trauma fragments experience into disconnected parts. Different aspects of self, each with characteristic somatic presentations, emerge in response to different triggers or contexts. Fisher, who co-authored Ogden’s second major textbook, contributed extensively to applying Sensorimotor Psychotherapy to complex trauma and dissociative disorders.

The method rests on recognition that most human behavior operates through procedural memory, our memory system for process and function. Procedural learning generates habitual, automatic responses reflected in movements, postures, gestures, autonomic arousal patterns, and emotional-cognitive tendencies. Unlike semantic or episodic memory, procedural memory does not require conscious recall. You do not remember how to ride a bicycle, you simply ride. Similarly, traumatic procedural learning does not involve remembering the trauma but rather automatically reenacting defensive responses whenever similar situations arise.

This has profound therapeutic implications. Talking about trauma activates semantic memory systems that may never have encoded the traumatic experience. What encoded instead were implicit patterns, the felt sense of danger, the defensive response, the defeat or collapse when defense failed. These implicit memories remain inaccessible to verbal processing, which explains why trauma survivors often report that talking about their experiences provides temporary relief but no lasting change. The talking occurs in wrong neural networks.

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy addresses this by using physical action and body sensation as primary vehicles for change. Rather than talking about what happened, the therapist guides attention to what is happening now in the body. How does the client sit? Where is tension held? How does breathing change when certain topics arise? What impulses toward movement appear? These present-moment somatic experiences provide direct access to procedural memory systems where trauma persists.

The approach operates through three phases that parallel van der Kolk and other trauma specialists’ phase-oriented models. Phase One focuses on safety and stabilization, helping clients develop capacity to observe their experience without becoming overwhelmed. This requires building what Ogden calls a “window of tolerance,” the zone of arousal within which processing can occur. Too much activation pushes clients into hyperarousal, sympathetic fight-flight, or hypoarousal, dorsal vagal shutdown. Too little activation produces no therapeutic change.

Mindfulness serves as the fundamental tool for staying within the window. Ogden emphasizes present-moment, nonjudgmental awareness of body sensations, movements, and impulses. This differs from cognitive mindfulness that focuses on thoughts and emotions. Somatic mindfulness attends to the body as it is, noticing tension without trying to relax, observing the impulse to flee without fleeing, feeling the constriction in the chest without immediately needing to change it.

This capacity to observe experience without being overwhelmed by it or compulsively acting on it represents precisely what trauma disrupts. Traumatic activation hijacks awareness, collapsing the space between stimulus and response. The threat appears and the body reacts before consciousness can intervene. Mindfulness practice gradually restores that space, allowing clients to notice activation as it begins rather than discovering they have already dissociated, panicked, or collapsed.

Phase One also involves resourcing, strengthening whatever helps clients feel safer, more grounded, more capable. Resources can be external, people or places or activities that provide support, or internal, qualities like strength, determination, or compassion. Ogden emphasizes embodied resourcing, finding how resources manifest somatically. When clients think of their grandmother who always believed in them, where do they feel that in their body? How does their posture shift? What happens to their breathing? Can they strengthen that felt sense?

This somatic anchoring makes resources more accessible during dysregulation. Thinking about grandmother when panicking may not work if the panic has shut down cognitive access. But the body remembers how grandmother’s presence felt, and accessing that somatic memory can help shift arousal states even when thinking is offline.

Phase Two involves processing traumatic material, carefully approaching the somatic components of traumatic memory. This phase requires skillful pacing, ensuring clients remain within their window of tolerance while working with material that historically overwhelmed them. Ogden uses the concept of “titration,” processing small amounts of activation at a time, and “pendulation,” moving between activation and resource, between contact with traumatic material and contact with safety.

Processing focuses not on the narrative of what happened but on the somatic narrative, what the body is telling through posture, gesture, breathing, muscle tension, autonomic activation. A client might be verbally recounting a childhood incident in calm tones while their body exhibits fight responses, fists clenched, jaw tight, breathing shallow. The somatic narrative reveals what narrative misses.

The therapist tracks these somatic signals and brings them into awareness. “I notice your fists are clenched. Can you feel that?” This simple intervention redirects attention from story to sensation, from past to present, from what was to what is. The client’s awareness shifts to their body in this moment rather than their mind in the past. This shift, repeated thousands of times across treatment, gradually builds capacity to stay present with activated states.

Ogden then explores the action tendencies embedded in the somatic patterns. The clenched fists suggest an impulse toward what? Hitting? Pushing away? Defending? When the client slows down enough to track their experience moment by moment, they often discover movements that were interrupted. The fists wanted to push away the perpetrator but the child was too small or too frightened or received the message that fighting back would make things worse. The pushing movement got arrested before completion.

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy supports completing these defensive movements in safe therapeutic context. The therapist might say, “What if your fists could do what they’re preparing to do? What wants to happen?” The client might begin pushing against a pillow, or pushing away in the air, or even just allowing awareness of the desire to push. This completion does not require dramatic catharsis. Even subtle movements, executed mindfully, can discharge activation that has been held for decades.

The theoretical grounding comes from understanding that the nervous system is designed to return to equilibrium after threat. Fight and flight responses activate the sympathetic nervous system, preparing for vigorous action. If that action occurs, if the fight succeeds or the flight escapes danger, activation naturally discharges. The system completes its cycle and returns to ventral vagal social engagement. However, when defensive action cannot occur, when the child cannot fight an adult perpetrator or flee an inescapable situation, activation remains trapped in the system. The nervous system stays prepared for an action that never happened.

Decades later, reminders of the original trauma reactivate this preparation without the person understanding why. Their body moves toward fight or flight not because current danger exists but because unfinished defensive responses from the past are seeking completion. By supporting these completions in therapy, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy allows the nervous system to finally finish what it started, discharging held activation and returning to regulation.

Phase Three focuses on integration, consolidating gains from processing and helping clients embody new ways of being. Trauma produces characteristic physical and psychological patterns that limit functioning. Healing involves not just resolving traumatic activation but expanding what Ogden calls “movement vocabulary,” the range of physical and emotional expressions available to the person. Someone who learned to collapse into dorsal vagal shutdown whenever threatened now develops capacity to also mobilize, to set boundaries, to fight back when appropriate. Someone chronically locked in sympathetic hyperarousal learns to settle, to rest, to let down their vigilance when safe.

Integration requires practice. New patterns must be reinforced through repetition until they become procedural, as automatic as the old defensive responses. This cannot happen through insight alone. The body must practice new movements, new postures, new ways of breathing and orienting. Ogden uses exercises designed to strengthen specific capacities.

Straightening the spine, lengthening through the torso, helps integrate parts of self that felt shameful or bad. Shame typically produces collapsed posture, head down, chest concave, literally shrinking from view. Practices that gently encourage lengthening provide somatic experience of claiming space, standing upright, being visible. These postural shifts affect self-perception. The body standing tall sends different signals to the brain than the body curled in shame.

Pillow work offers trauma survivors ways to experience comfort, safety, and appropriate touch. For clients with ruptured attachment histories, hugging pillows provides the holding they never received. This might seem like childish exercise, but procedural memory does not distinguish practice from original experience. The body learns that soft contact can feel safe, that comfort is possible, that being held does not inevitably lead to violation.

Pushing movements help clients who froze during assault or abuse discover their capacity to defend boundaries. Someone who could not push away their perpetrator can now practice pushing against therapist’s hands, against walls, against pillows. Again, this works because procedural memory operates through action. The nervous system that learned “I cannot defend myself” begins learning “I can push back.” The latter becomes as automatic as the former, providing new options when boundaries are threatened.

For depth psychology practitioners, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy provides somatic methodology for working with what Jung described as the shadow. Shadow material consists of aspects of experience dissociated from conscious identity because they were overwhelming, shameful, or conflicted with required self-image. These disowned aspects do not disappear but remain active in the unconscious, emerging through symptoms, projections, and compulsive patterns.

Jung recognized that shadow work requires more than cognitive recognition. Insight that “I have anger” changes little if anger remains dissociated somatically. The person understands intellectually they feel anger but cannot access it because anger was so dangerous in childhood that it triggers automatic collapse. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy addresses this by helping clients track how shadow material manifests in the body. Where does the anger live? What happens physically when it begins to emerge? What defensive response immediately suppresses it?

By working directly with these somatic processes, clients gradually develop capacity to tolerate previously unbearable affects. The anger can be felt without the collapse that automatically suppressed it. The vulnerability can be experienced without the defensive aggression that covered it. Shadow integration happens not through thinking about disowned parts but through developing nervous system capacity to hold the activation these parts carry.

Complexes, in Jungian terms, represent emotionally charged networks with relative autonomy from conscious ego. When a complex is activated, the person may feel possessed, experiencing characteristic emotional states, somatic sensations, and behavioral impulses. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy treats complexes as trauma-based procedural patterns. Each complex has a somatic signature, a characteristic way the body organizes when that complex is active. Helping clients identify and track these signatures provides concrete entry point for working with what otherwise feels overwhelming and uncontrollable.

Internal Family Systems, developed by Richard Schwartz, shares recognition that psyche organizes into parts, each with its own perspective, feelings, and somatic presentations. While IFS works primarily through dialogue with parts, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy engages parts through their physical manifestations. A protective part that manifests as chronic shoulder tension, a child part that shows up as collapse and shallow breathing, an angry part expressed through jaw clenching. By attending to these somatic presentations, therapists can work with parts even when clients cannot yet identify or dialogue with them directly.

Active imagination, Jung’s method for engaging unconscious content, involves allowing spontaneous images, sensations, and impulses to arise and be observed. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy operationalizes this through mindful tracking of present-moment experience. Rather than deliberately directing imagination, the therapist guides attention to what is already happening somatically. What images arise when you notice that tension in your chest? What memory surfaces as you track the impulse to contract? The body provides entry point for material that might not emerge through directed visualization.

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy shares deep affinities with brainspotting, developed by David Grand. Both recognize that trauma encodes in subcortical networks accessed through somatic channels rather than cognitive processing. Both use therapist attunement to client’s present-moment experience rather than predetermined protocols. Both emphasize following the client’s process rather than imposing external structure. The primary difference is that brainspotting uses fixed eye position to access and process trauma while Sensorimotor Psychotherapy uses broader range of somatic interventions including posture, movement, breath, and sensation.

Similarly, connections exist with EMDR, developed by Francine Shapiro. Both approaches recognize that trauma overwhelms normal processing capacity, leaving disturbing material incompletely integrated. Both use present-moment interventions to facilitate processing. EMDR’s bilateral stimulation and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy’s somatic tracking both bypass cognitive defenses that prevent access to traumatic material. Many therapists integrate the approaches, using Sensorimotor techniques to help clients develop sufficient window of tolerance to engage EMDR processing, or using somatic tracking during EMDR sessions to notice when processing is occurring versus when client has dissociated.

Ogden’s influence on the trauma field extends through her publications, training programs, and collaborative relationships with other leaders. Her 2006 book Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy, co-authored with Kekuni Minton and Clare Pain, became foundational text for somatic trauma treatment. Published in Norton’s Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology, it provided comprehensive integration of neuroscience research with clinical technique, demonstrating how body-centered interventions address specific neurobiological effects of trauma.

The book’s reception signaled changing attitudes in mainstream clinical psychology. Bessel van der Kolk praised it as breakthrough in trauma treatment, expertly explaining how using body sensation and movement can heal trauma’s wounds. Stephen Porges noted Ogden’s brilliant decoding of the crucial role body plays in regulating physiological, behavioral, and mental states. Allan Schore called it a remarkable integration of theory and clinical practice informed by research in trauma, attachment, infancy, and neurobiology.

Her 2015 book Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment, co-authored with Janina Fisher, provided practical guide for integrating Sensorimotor techniques into treatment. Each chapter includes clinical guides for applying concepts and worksheets for clients to integrate material personally. The book emphasizes that Sensorimotor Psychotherapy functions as adjunct to and support of other treatment methods rather than standalone manualized approach.

Most recently, The Pocket Guide to Sensorimotor Psychotherapy in Context (2021) addresses how sociocultural factors including racism, oppression, and marginalization affect both trauma and treatment. Ogden worked with four consultants who center social justice and sociocultural awareness in their work, expanding Sensorimotor Psychotherapy beyond individually focused trauma treatment to recognize systemic and cultural wounds.

The book presents numerous composite cases with diverse clients, demonstrating how to apply Sensorimotor principles while maintaining sensitivity to how oppression and marginalization impact somatic presentations, attachment patterns, and capacity to trust therapeutic relationships. Someone whose trauma includes racialized violence, whose body has been objectified or violated in ways connected to their identity, requires different considerations than someone with interpersonal trauma unconnected to systemic oppression. The somatic imprints differ, as do the resources and barriers to healing.

Ogden is currently developing Sensorimotor Psychotherapy for children, adolescents, and families with Dr. Bonnie Goldstein. Adapting the approach for younger clients and family systems requires modifications that account for developmental differences and relational contexts. Children may not have verbal capacity to describe their experience but their bodies tell clear stories through play, movement, and interaction. Family applications recognize that trauma affects entire systems, with each member developing characteristic somatic patterns in response to family dynamics.

The Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute, which Ogden founded and directs, provides comprehensive training in the approach through Level 1, 2, and 3 trainings offered internationally. Thousands of therapists have completed these extensive programs, which combine didactic instruction with supervised practice and personal experiential work. The training emphasizes that effective Sensorimotor therapy requires therapists to develop their own somatic awareness and regulation capacities. They must be able to track their own body’s responses during sessions, noticing when they are regulated versus dysregulated, when they are present versus dissociated.

The institute also sponsors research investigating Sensorimotor Psychotherapy’s effectiveness. Preliminary studies show significant improvements in body awareness, anxiety reduction, and capacity for self-soothing when comparing treatment to control conditions. Research on the Trauma-Based Groups, which apply Sensorimotor principles in group format, provides evidence that the approach helps complex trauma survivors develop greater body awareness, increase capacity for self and relational soothing, and reduce anxiety symptoms.

Ogden’s current interests extend beyond trauma treatment to include what she calls Embedded Relational Mindfulness, the cultivation of present-moment awareness within therapeutic relationship itself. This involves both therapist and client developing capacity to track the implicit, nonverbal, somatic dimensions of their interaction. How do bodies orient toward each other or pull away? What happens in each person’s system when particular topics arise? How do arousal states synchronize or become dysynchronized?

This attention to the relational field draws from infant research, particularly the work of Ed Tronick, Daniel Stern, and Beatrice Beebe on how parent-infant dyads regulate each other through micro-level somatic synchrony. What these researchers discovered about early development applies equally to therapy. Healing happens through thousands of moments of attunement and misattunement and repair, therapist and client learning together how to stay connected across different arousal states.

Ogden also explores the relational nature of shame, recognizing that shame involves not just negative self-evaluation but somatic collapse, disconnection from self and others, and profound loneliness. Healing shame requires relational experiences that contradict shame’s core message that the self is defective and unworthy of connection. The therapist’s steady, nonjudgmental presence while client experiences shame provides crucial somatic-relational experience. The body learns it can feel shame without being abandoned, that shame is tolerable affect rather than catastrophic state requiring immediate defense.

Her interest in presence, consciousness, and philosophical-spiritual principles underlying Sensorimotor Psychotherapy reflects recognition that technique alone does not produce healing. The therapist’s quality of presence, their capacity to remain embodied, grounded, and open while meeting client’s pain, creates conditions for transformation. This cannot be taught mechanically but requires therapists to develop their own contemplative practices, their own relationship with presence.

Critics of Sensorimotor Psychotherapy note that empirical research base, while growing, remains limited compared to more established approaches like cognitive behavioral therapy or EMDR. Controlled studies demonstrating effectiveness across diverse populations and problems are needed. However, this limitation applies to most body-centered approaches, which have historically received less research funding than cognitive-behavioral methods despite widespread clinical use.

Some question whether somatic interventions work through proposed mechanisms or through other factors like therapeutic relationship, expectancy effects, or simple exposure to traumatic material. Distinguishing specific effects of somatic techniques from general therapy factors requires research designs that control for these variables. Such studies are underway but results remain preliminary.

Additionally, questions arise about training requirements and quality control. As Sensorimotor Psychotherapy gains popularity, concerns emerge about inadequately trained practitioners using techniques without sufficient understanding of trauma dynamics, contraindications, or ethical boundaries. The institute has developed comprehensive training standards but cannot prevent poorly trained individuals from claiming to practice the approach.

Despite these concerns, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy has proven enormously influential in expanding trauma treatment beyond purely verbal approaches. Ogden’s insistence that the body must be engaged directly rather than as afterthought or adjunct to talk therapy has been vindicated by accumulating neuroscience research showing how trauma affects subcortical systems inaccessible to language. Her emphasis on present-moment somatic awareness rather than narrative reconstruction addresses criticism that traditional trauma therapy risks retraumatization through excessive focus on traumatic content.

The approach has helped shift the broader field toward bottom-up interventions that work with the body’s innate capacity for regulation and healing rather than imposing top-down cognitive control. This represents significant evolution from mid-twentieth century psychotherapy that treated the body as problem to be overcome through mental discipline or object to be analyzed through interpretation.

For Jung-influenced practitioners, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy provides concrete methods for working with material that depth psychology recognizes but often addresses primarily through verbal-symbolic means. Shadow work, complex integration, active imagination, and individuation all benefit from somatic grounding. The unconscious speaks not just through dreams and symbols but through chronic tension, arrested movements, and autonomic patterns. Attending to these somatic expressions provides additional channel for engaging unconscious material.

Ogden’s legacy extends through thousands of therapists trained in Sensorimotor approaches, through her influential textbooks that have shaped trauma treatment internationally, and through her leadership in establishing somatic psychology as legitimate specialization within mainstream clinical practice. Her work demonstrates that the body is not peripheral to psychological healing but central, that trauma recovery requires engaging the nervous system directly, and that mindfulness-based somatic interventions can access and transform material that remains untouched by talk therapy alone.

Her partnership with Janina Fisher has been particularly generative, with Fisher’s expertise in structural dissociation and parts work complementing Ogden’s somatic focus. Together they have shown how recognizing different self-states or parts, each with characteristic somatic presentations, provides framework for working with the fragmentation trauma produces. Rather than seeking unified coherent self, they help clients develop relationships among parts, allowing different aspects of experience to communicate and cooperate.

Ogden’s emphasis on therapist self-awareness and personal practice challenges the medical model that treats therapist as neutral technical expert. Effective somatic therapy requires therapists to know their own bodies, to track their own activation, to notice when their defensive patterns emerge. This ongoing self-work is not preliminary training that eventually completes but career-long practice. The therapist’s body is instrument through which they sense client’s implicit communications and provide attuned responses.

This recognition connects to broader movement in psychotherapy toward emphasizing therapist presence, authenticity, and relational engagement over technique and protocol. While Sensorimotor Psychotherapy includes specific interventions and structured phases, Ogden insists these must be applied within context of genuine therapeutic relationship characterized by mindful awareness and compassion. The technique serves relationship rather than replacing it.

What Ogden has accomplished fundamentally is demonstrating that trauma treatment cannot rely on talking alone, that the body holds wisdom and pain beyond verbal articulation, and that healing requires meeting clients in the somatic realm where trauma actually lives. This insight, obvious in retrospect but revolutionary when first proposed, has transformed how thousands of therapists understand and practice trauma treatment.

Timeline of Pat Ogden’s Career and Major Contributions

Early 1970s: Works as technician and yoga/dance instructor at short-term psychiatric hospital, begins observing mind-body connections

Early 1970s: Begins apprenticing with Ron Kurtz, becomes certified in Hakomi before formal trainings exist

Late 1970s: Designs original Hakomi Institute curriculum as Educational Director

Late 1970s: Co-teaches first Hakomi training with Kurtz, becomes first person certified in Hakomi

1981: Co-founds Hakomi Institute with Ron Kurtz and core group

1981: Founds own school, initially Hakomi Bodywork, later Hakomi Integrative Somatics

1985-2005: Faculty member at Naropa University

1980s-1990s: Develops Sensorimotor Psychotherapy through clinical work with trauma and sexual abuse survivors

2000s: Hakomi Integrative Somatics becomes Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute

2002: First published paper on Sensorimotor Psychotherapy approach

2006: Published Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy (with Kekuni Minton and Clare Pain) in Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology

2015: Published Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment (with Janina Fisher) in Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology

2016: Research study published on Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Group Therapy effectiveness for complex PTSD

2021: Published The Pocket Guide to Sensorimotor Psychotherapy in Context in Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology

Present: Developing Sensorimotor Psychotherapy for children, adolescents, and families with Dr. Bonnie Goldstein

Present: Founder and Education Director of Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute

Present: International lecturer, trainer, consultant, and clinician

Present: Named Legacy Holder for Hakomi Education Network by Ron Kurtz

Complete Bibliography of Major Works by Pat Ogden

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Ogden, P. (2021). The Pocket Guide to Sensorimotor Psychotherapy in Context. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Ogden, P., Pain, C., & Fisher, J. (2006). A sensorimotor approach to the treatment of trauma and dissociation. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(1), 263-279.

Gene-Cos, N., Fisher, J., Ogden, P., & Cantrel, A. (2016). Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Group Therapy in the Treatment of Complex PTSD. Annals of Psychiatry and Mental Health, 4(1).

Influences and Legacy

Ogden’s work builds on Ron Kurtz’s Hakomi Method, which pioneered mindfulness-based body-centered psychotherapy integrating Buddhism, Taoism, and systems theory. From Kurtz she learned that “clients are not problems to be solved, they’re experiences waiting to happen,” emphasizing process over content, being over doing.

The Rolf Method of Structural Integration influenced understanding of how habitual postures and movement patterns reflect and perpetuate psychological patterns. Gestalt therapy contributed emphasis on present-moment awareness and completing unfinished business. Neuroscience research by Allan Schore, Bessel van der Kolk, Stephen Porges, and Ruth Lanius provided empirical foundations for somatic approaches.

Attachment research, particularly work by Edward Tronick on mutual regulation and Beatrice Beebe on microanalysis of mother-infant interaction, informed understanding of how therapeutic relationship facilitates regulation. Research on dissociation and structural dissociation by Onno van der Hart, Ellert Nijenhuis, and Janina Fisher contributed frameworks for understanding trauma’s fragmenting effects.

Ogden has profoundly influenced contemporary trauma treatment. Bessel van der Kolk integrates Sensorimotor principles into the Trauma Center at JRI and references Ogden’s work extensively. Janina Fisher co-authored major texts and applies Sensorimotor approaches to treatment of structural dissociation. Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing shares emphasis on completing defensive responses and tracking somatic experience.

David Grand’s brainspotting similarly recognizes trauma’s subcortical encoding and uses somatic tracking. Richard Schwartz’s Internal Family Systems shares understanding of parts with distinct somatic presentations. These approaches, while technically different, share philosophical commitment to engaging body directly in trauma treatment.

Thousands of therapists worldwide have trained in Sensorimotor Psychotherapy through the institute’s comprehensive programs. The approach has been adopted in diverse settings including VA hospitals, community mental health centers, private practices, and residential treatment facilities. Its influence extends to related fields including dance therapy, somatic coaching, and contemplative practices.

For depth psychology, Ogden’s greatest contribution involves providing concrete somatic methods for working with unconscious material. Rather than relying solely on verbal interpretation of symbols and associations, therapists can track how unconscious content manifests in posture, gesture, movement, and sensation. Shadow work, complex integration, and active imagination all become more accessible through somatic engagement.

0 Comments