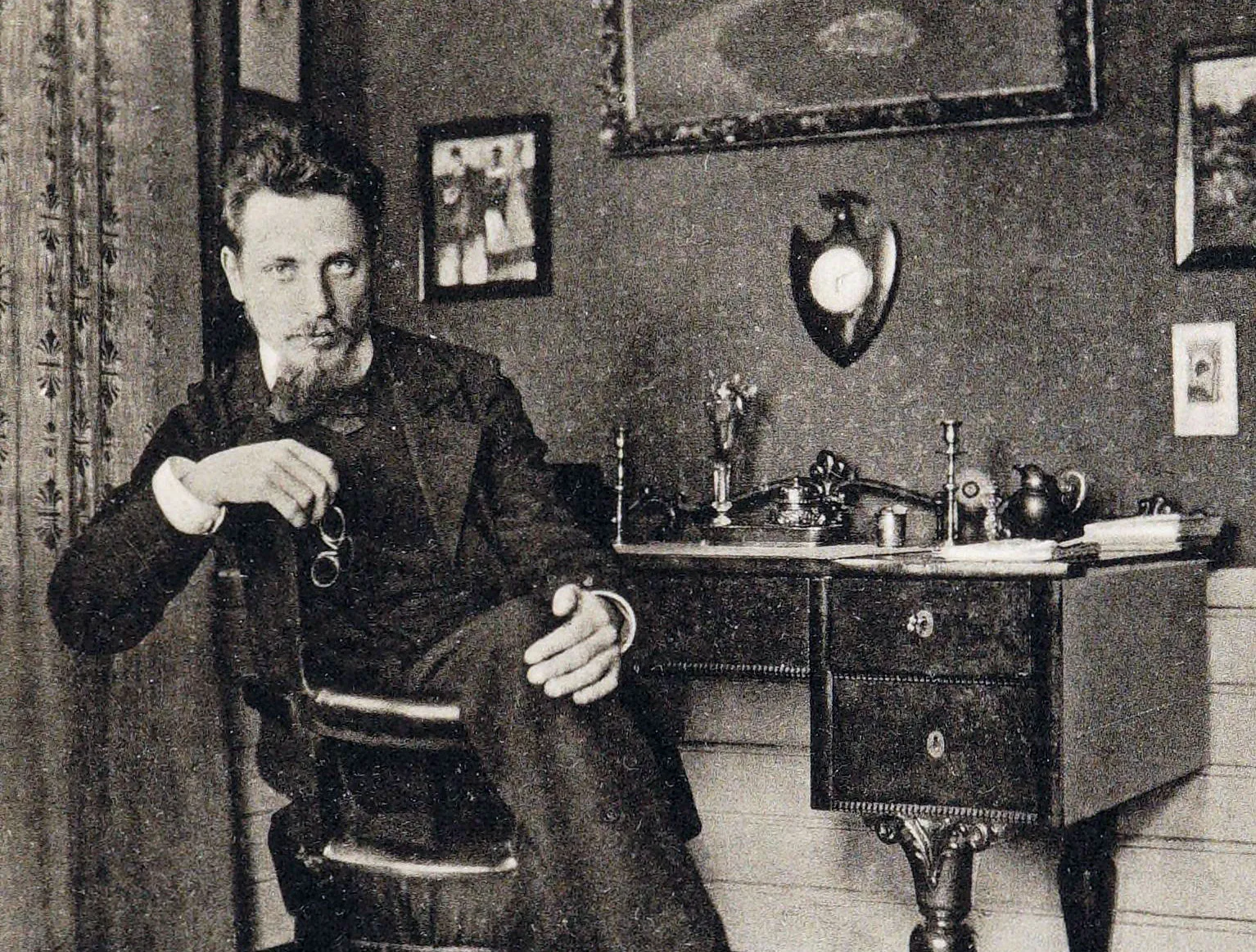

Who was Rainer Maria Rilke?

“Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depth of your heart; confess to yourself you would have to die if you were forbidden to write.” ― Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

Rainer Maria Rilke, an Austrian poet and novelist who lived from 1875 to 1926, is widely recognized as one of the most lyrically intense and spiritually profound poets in the German language. His work explores themes of solitude, the inner life, the beauty of the natural world, and the search for meaning in an uncertain reality. Rilke’s poetic vision invites readers to venture into the depths of their own souls and discover the transformative power of art and imagination.

Main Ideas:

- Rilke was an Austrian poet acclaimed for his lyrically intense and spiritually profound poetry that explores themes of solitude, imagination, beauty and meaning.

- He introduced the concept of “inwardness” as an essential quality and task for the artist.

- Rilke believed poetic creation arises from an inner necessity of the soul and requires solitude, patience and receptivity to the beauty of the world.

- He emphasized the transformative power of art to shape and deepen human experience.

- Rilke’s famous poetic alter-ego is the “Angel” which embodies an ideal of wholeness, beauty and more-than-human consciousness.

- His “Letters to a Young Poet” contain enduring wisdom on the creative process, solitude, love, and how to live the questions of one’s inner being.

- Rilke drew inspiration from visual art, especially the sculpture of Rodin, visiting Russia, and the landscape of Duino castle.

- Major works include “New Poems”, “The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge”, “Duino Elegies” and “Sonnets to Orpheus.”

- His poetry influenced many 20th century writers and continues to have a devoted international readership.

- Despite personal challenges, Rilke maintained an extraordinary discipline and dedication to his art throughout his life.

The Artist’s Inner World

Central to Rilke’s understanding of the artist is the cultivation of a rich interior life – what he called “inwardness.” For Rilke, the artist’s fundamental task is to venture into his own soul, confront its dark and light dimensions, and transmute lived experience into art. This requires solitude, patience, and a radical receptivity to both beauty and suffering.

In his famous “Letters to a Young Poet”, Rilke advises an aspiring writer: “There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write.” Poetry, for Rilke, is not a matter of choice or ambition, but of inner necessity. The artist is one who cannot help but create, for whom art is as essential as breathing.

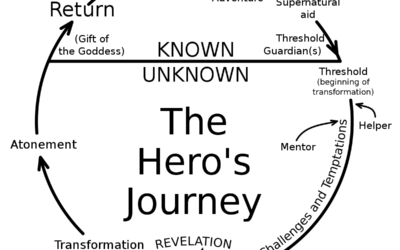

This understanding of art as arising from the soul’s depths resonates with the psychological concept of individuation developed by Carl Jung. For Jung, individuation is the lifelong journey of becoming more fully oneself – a process that requires courageous encounter with the unconscious and its symbols. The artist, attuned to this inner world, plays a crucial role in giving form to the soul’s truth.

Art, Beauty and Transformation

Rilke saw art not as an escape from reality, but as a way of more deeply inhabiting and transforming it. In his poems, the visible world shimmers with an almost sacred radiance, inviting the reader to perceive anew the marvels of existence. A rose, a panther, an archaic torso – through Rilke’s eyes, these ordinary things become thresholds to an experience of intense aliveness and meaning.

This revelatory power of art is embodied in Rilke’s famous poetic alter-ego: the Angel. Neither a conventionally religious figure nor a decorative motif, the Rilkean Angel is an ideal of wholeness, beauty, and more-than-human consciousness. “Every Angel is terror”, Rilke wrote, evoking the awe-inducing strangeness of a being who “effortlessly moves through the uncharted depths of human feeling that we can only experience in dreams”.

Rilke’s “Duino Elegies,” a profound meditation on the beauty and suffering of existence, begins with an invocation of the angelic. Throughout the cycle, the poet wrestles with the Angel as a personification of the immense richness of being to which humans only have partial access. Yet in striving to see with the Angel’s eyes, Rilke suggests, we may be transfigured by a new attentiveness to the world in all its terror and splendor.

The Poetic Vocation

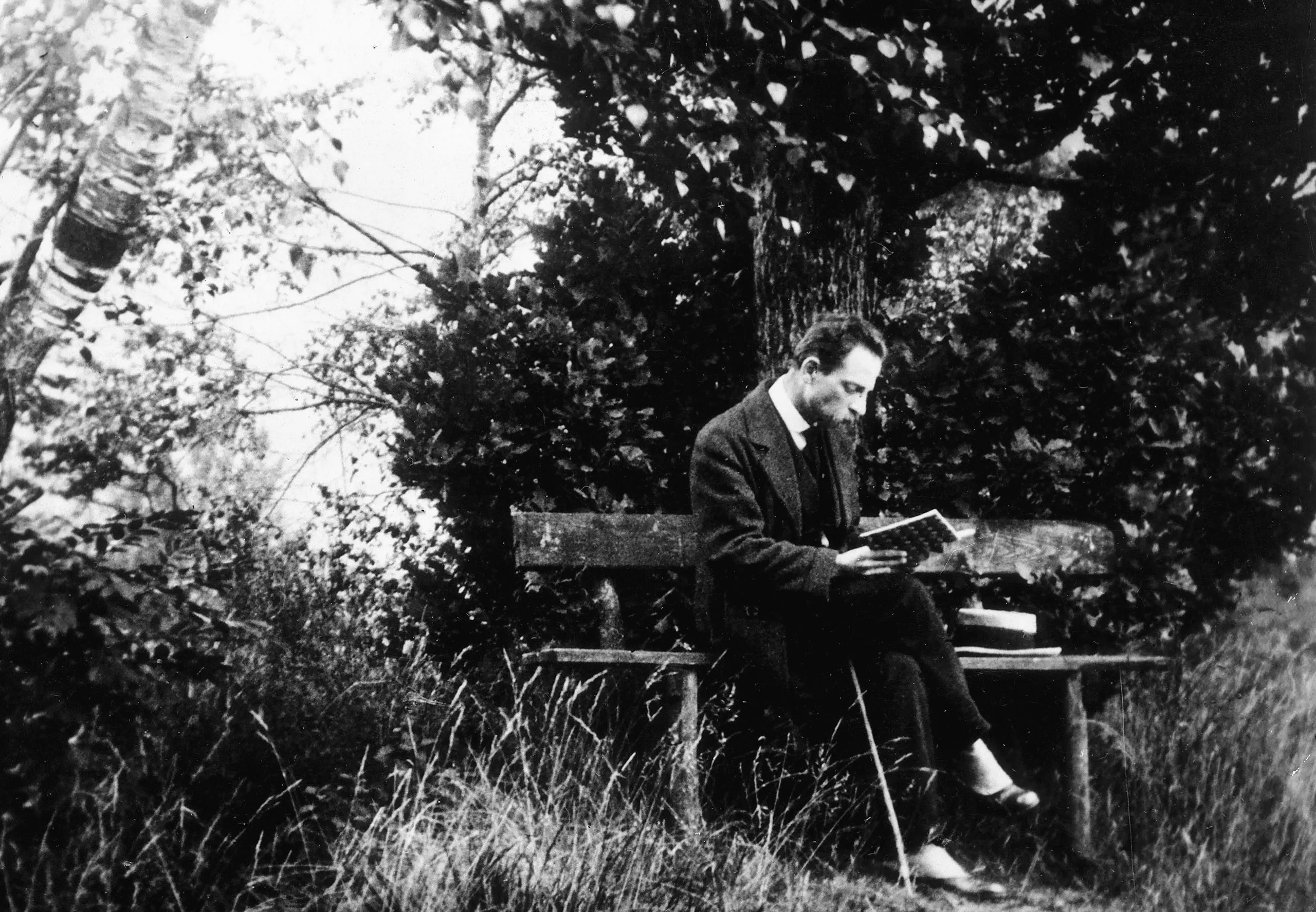

For Rilke, the poet’s vocation is a sacred calling that requires unwavering dedication in the face of life’s vicissitudes. In his own life, Rilke faced many challenges – financial insecurity, tumultuous relationships, and debilitating illnesses. Yet he maintained an extraordinary discipline and devotion to his art, spending hours each day in solitary reading, reflection, and composition.

Rilke’s commitment to the poetic life was nourished by his travels and encounters with art and nature. His sojourns in Paris, where he worked briefly as secretary to the sculptor Auguste Rodin, attuned him to the expressive power of visual forms. His visits to Russia immersed him in the spirituality of icon painting and folk creativity. And his long stays at Duino castle on the Adriatic Sea provided the solitude and elemental landscapes that inspired his greatest works.

Throughout his correspondence and poetry, Rilke offered a vision of the artist as one whose ultimate task is to praise and affirm life in all its mystery. “The purpose of life is to be defeated by greater and greater things”, he wrote. For Rilke, the act of poetic creation was a way of rising to this challenge – not an escape from the world’s darkness, but a heroic encounter with its unfathomable depths.

Rainer Maria Rilke’s Life and Work

Early Life and Education

Rainer Maria Rilke was born on December 4, 1875, in Prague, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His childhood was marked by a strained relationship with his militaristic father and an emotionally distant mother. Rilke was educated first at a military academy, then at universities in Prague and Munich, where he studied literature, art history, and philosophy.

While still a student, Rilke published his first poetry collections, “Life and Songs” (1894) and “Sacrifice to the Lares” (1895). Though derivative of his German Neo-Romantic predecessors, these early works already exhibit Rilke’s preoccupation with themes of solitude, spiritual crisis and metamorphosis through art.

Major Published Works

Rilke’s creative output – spanning lyric and narrative poetry, essays, fiction and over 1,000 published letters – is indelibly marked by his encounter with various European landscapes and cultural currents. His major works include:

“New Poems” (1907-1908): This two-volume collection cemented Rilke’s reputation as a major lyric poet. In these intensely visual, musical works, Rilke showcased his talent for transforming precise observations into symbolic language, evoking both the splendor and the transience of the world.

“The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge” (1910): Rilke’s only novel, presented as the fictional journals of a young Danish artist, is a haunting meditation on the challenges of poetic creation in the modern metropolis. Often cited as a pioneering work of literary modernism.

“Duino Elegies” (1923): An anguished yet affirming monologue on human existence and our search for connection with the invisible world, composed over a decade marked by war and personal crises. Rilke conceived the first lines during a stay at Duino Castle near Trieste.

“Sonnets to Orpheus” (1923): This virtuosic 55-poem cycle, written in a creative burst alongside the final Elegies, mythologizes the power of poetry and celebrates the cycles of death and rebirth. The Sonnets are at once a memorial to a deceased young dancer and a self-reflexive ars poetica.

“Letters to a Young Poet” (1929): Published after Rilke’s death, this collection of ten letters, written to a young military cadet, contains some of Rilke’s most quoted guidance on surviving solitude, remaining patient in artistic development, and learning to love.

Influence and Legacy

Rilke’s poetry had a profound impact on many 20th century writers, from W.H. Auden and Marina Tsvetaeva to Yannis Ritsos and Nina Cassian. His work has been translated into over 50 languages and continues to find devoted readers around the world.

Philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and Hans-Georg Gadamer have drawn on Rilke’s metaphysical lyricism, while psychologists like Robert Romanyshyn see him as a profound explorer of the phenomenology of imagination. Rilke has been a fertile source of inspiration for other arts as well, including modern dance, classical music and visual art.

More than any esoteric doctrine, however, Rilke imparts to his readers an attitude of patient questioning, cultural erudition, and faith in language as mankind’s supreme aid in confronting the mystery of existence. In the spirit of his iconic line from the Archaic Torso of Apollo – “You must change your life” – Rilke’s poetic legacy is above all an invitation to venture beyond the familiar habits of perception into the labyrinth of the self and its creative capacities.

Bibliography

Rilke, R.M., and Herter Norton, M. (1992). Letters to a Young Poet. San Jose City: BN Publishing. Rilke, R.M., & Snow, E. (2009). New Poems: A Bilingual Edition. New York: North Point Press. Rilke, R.M., Seamus Heaney (Introduction) & Stephen Cohn (Translator). (2011). Duino Elegies and The Sonnets to Orpheus: A Dual-Language Edition With Parallel Text. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Rilke, Rainer M., & Bancroft, A. (2016). The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. London: Hesperus Press. Further Reading: Baer, Ulrich. Rilke and The Poetics of Experience. Columbia University Press, 1997. Finck, M. (2009). A Phenomenology of Poetry: Rainer Maria Rilke. In N. Liska & L. Kronick (Eds.), Literature and Phenomenology. Fordham University Press. Romanyshyn, Robert. The Wounded Researcher: Research with Soul in Mind. New Orleans: Spring Journal Books, 2007. Tavis, Anna A. and Breon Mitchell. Rainer Maria Rilke: Inventions of Reading. Peter Lang, 2003. Gadamer, Hans-Georg. “Are the Poets Falling Silent,” Gadamer on Celan: “Who Am I and Who Are You?” and Other Essays. Translated and Edited by Richard Heinemann and Bruce Krajewski. Albany: State University of New York, 1997. Komar, Kathleen L. “The Issue of Transcendence in Rilke’s ‘Duineser Elegien’.” Orbis Litterarum 41 (1986): 39-54. Slochower, Harry. “Rainer Maria Rilke: The Alchemy of Alienation.” Rainer Maria Rilke: Masks and the Man. By H. F. Peters. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1966.

Philosophy

0 Comments