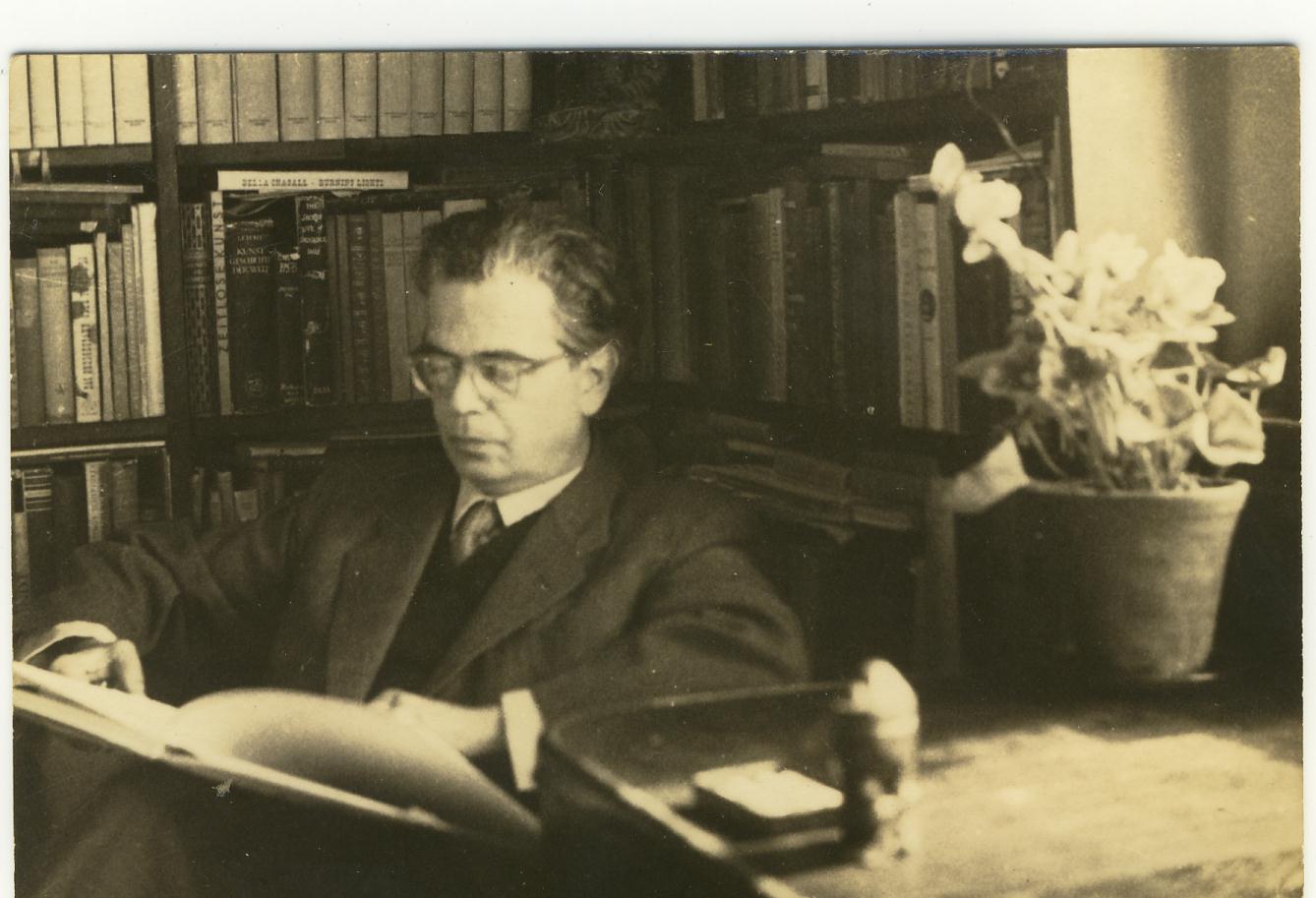

Who was Erich Neumann?

Erich Neumann (1905-1960) was a prominent German psychologist, philosopher, and scholar who made seminal contributions to the field of analytical psychology. A close collaborator and protégé of Carl Jung, Neumann played a key role in expanding and systematizing Jungian theory, particularly in the areas of feminine psychology, the origins of consciousness, and the archetypal stages of human development.

Neumann’s prolific body of work, though less well-known today than Jung’s, offers profound insights into the universal patterns that shape the psyche. Drawing on mythology, anthropology, art history, and clinical case studies, he traced the evolution of consciousness from its primitive beginnings to the emergence of the modern individual. In particular, his theory of the “Great Mother” archetype and his mapping of the “stages of consciousness” have had an enduring influence on Jungian thought and beyond.

This essay provides an in-depth exploration of Neumann’s key ideas and their significance for our understanding of the human psyche. It situates his work within the broader context of depth psychology and assesses its continuing relevance for contemporary theory and practice. Finally, it offers a retrospective on Neumann’s legacy, examining which of his ideas have stood the test of time, which have been modified or discarded, and how his work compares to that of later figures like James Hillman.

Resources on Erich Neumann

- Official Website: Erich Neumann Resources

- Books: The Origins and History of Consciousness Princeton University Press

- YouTube Lecture: Neumann and the Archetypes

- Biography: Neumann’s Life

- Lecture Series: Eranos Lectures

- Article: Neumann’s Contribution to Depth Psychology

- Institute: Jung-Neumann Letters

- Podcast: Neumann and Creativity

- Archive: Neumann Archives

- Quotes: Neumann Quotes

Main Ideas and Key Points:

- Neumann’s work expands and systematizes Jungian theory, particularly in the areas of feminine psychology, the origins of consciousness, and the archetypal stages of human development.

- Central to Neumann’s thought is the idea that the psyche unfolds through a series of universal, archetypal stages, from the “uroboric” fusion of infancy to the mature integration of the self.

- Neumann’s magnum opus, The Origins and History of Consciousness, traces this development through an analysis of mythological motifs, proposing that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny in the growth of the individual psyche.

- In his complementary work, The Great Mother, Neumann explores the fundamental role of the feminine archetype in this unfolding, as both a nurturing and terrifying presence that must be integrated for wholeness.

- Neumann’s understanding of the “ego-Self axis” and the “centroversion” of libido provides a dynamic model of individuation, in which the ego must separate from and then realign with the archetypal Self.

- Neumann also made significant contributions to the study of art and creativity, seeing the artist as a “seer” and “shaper” who mediates between the collective unconscious and the culture.

- In his analysis of the psyche’s evolution from “matriarchal” to “patriarchal” consciousness, Neumann anticipated later feminist critiques, while seeking to honor the necessity of both principles.

- However, some of Neumann’s ideas, such as the strict gendering of archetypes and the universality of the developmental stages, have been challenged by subsequent thinkers.

- Jungian successors like James Hillman built on Neumann’s archetypal insights while departing from his more linear, developmental approach in favor of a “polytheistic” vision of the psyche.

- Despite these critiques, Neumann’s work remains a rich and generative resource for depth psychology, offering a compelling vision of the archetypal foundations of human experience.

- The Origins and History of Consciousness

Neumann’s magnum opus, The Origins and History of Consciousness, is a sweeping exploration of the archetypal stages of human development, both in the individual and the collective. Drawing on mythology, religion, and cultural history, Neumann traces the evolution of consciousness from its primitive beginnings to the emergence of the modern self.

At the heart of Neumann’s theory is the idea that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny – that is, that the development of the individual psyche mirrors the evolution of human consciousness as a whole. Just as humanity has passed through certain universal stages in its collective history – from the “uroboric” fusion of primitive society to the differentiated consciousness of modernity – so too does each individual recapitulate this journey in their own psychological growth.

Neumann identifies several key stages in this archetypal unfolding:

The Uroboros:

The primary, undifferentiated state of infancy, in which the child experiences no distinction between self and world, between inner and outer. This is the realm of the “Great Mother” archetype, the all-encompassing presence that both nurtures and devours.

The Great Mother:

The emergence of the “primal relationship” between mother and child, which sets the stage for all future development. Here the psyche begins to differentiate from the uroboric fusion, but remains embedded in the powerful field of the feminine archetype.

The Separation of the World Parents: The dawning awareness of the “World Parents” – the great masculine and feminine principles that underlie all of reality. In myth, this is often represented as the separation of Sky Father and Earth Mother, the polarization of spirit and matter.

The Birth of the Hero:

The emergence of the heroic ego, which struggles to free itself from the grip of the Great Mother and assert its own agency in the world. This is the stage of the “dragon fight,” the battle against the regressive pull of the unconscious.

The Slaying of the Mother:

The hero’s ultimate victory over the Great Mother, which liberates the ego from its primal dependence but also cuts it off from the nourishing roots of the unconscious. This is a necessary but dangerous stage, which risks inflating the ego and denying the feminine.

The Transformation of the Hero:

The reorientation of the hero’s energy from conquest to service, as he learns to put his powers in the service of the greater good. This often involves a “night sea journey,” a descent into the depths of the psyche to recover the lost feminine and reconnect with the Self.

For Neumann, these stages are not simply a linear progression, but a dialectical spiral in which each level is transcended and integrated into the next. The goal is not to reject or repress the earlier stages, but to consciously embrace and transform them, uniting the opposites of masculine and feminine, ego and unconscious, in a higher synthesis.

At each stage, Neumann shows, the psyche is shaped by certain archetypal “Ur-fantasies” – primal, mythic images that structure our experience of self and world. These include motifs like the world egg, the divine child, the tree of life, the sacred marriage, and the mandala. By studying these universal symbols, Neumann believed, we can gain insight into the deep grammar of the soul, the timeless patterns that underlie all human development.

-

The Great Mother

In a complementary work, The Great Mother, Neumann explores the fundamental significance of the feminine archetype in human history and psychology. Building on Jung’s concept of the “anima,” Neumann argues that the Great Mother is a universal, cross-cultural symbol that represents the origins and matrix of all life.

The Great Mother, Neumann shows, is a multifaceted and ambivalent figure, encompassing both positive and negative aspects. On the one hand, she is the nourishing, protective, life-giving source, the womb from which all things emerge and to which they return. She is associated with the earth, the waters, the moon, and the cyclical rhythms of nature. In this beneficent aspect, she is the Good Mother, the Madonna, the Goddess of Love.

But the Great Mother also has a dark, terrifying side. She is the devouring mother, the Terrible Mother, the Gorgon and the Medusa. In this aspect, she represents the destructive, engulfing power of the unconscious, the chaotic abyss that threatens to swallow up the fragile ego. She is the archetypal force behind the fear of castration, the dread of dissolution and death.

For Neumann, the task of human development is to integrate these two faces of the feminine, to embrace both the nurturing and the transformative powers of the Great Mother. This requires a descent into the depths of the unconscious, a confrontation with the shadow side of the psyche. Only by facing and assimilating the darkness within can the ego hope to achieve a mature, balanced relationship with the archetypal feminine.

Neumann traces this process through a wide range of mythological and cultural examples, from the Sumerian goddess Inanna to the medieval cult of the Virgin Mary. He shows how the evolution of human consciousness has been marked by a gradual differentiation from the primordial unity of the Great Mother, a separation of masculine and feminine principles that has been both liberating and traumatic.

In particular, Neumann argues, the rise of patriarchal culture has led to a repression and devaluation of the feminine, a one-sided emphasis on masculine values of individuation, rationality, and control. This has created a deep imbalance in the psyche, a split between conscious and unconscious that can only be healed through a new integration of opposites.

For Neumann, this integration is the key to psychological wholeness and spiritual realization. By embracing the Great Mother in all her aspects, by honoring the feminine within and without, we can transcend the dualistic divisions of the ego and awaken to our true nature as children of the divine. This is the goal of the individuation process, the ultimate aim of Jungian analysis and self-realization.

-

Art and the Creative Unconscious

In addition to his theoretical work, Neumann was also a keen student of art and creativity. He saw the artist as a kind of “seer” or “shaper,” a mediator between the collective unconscious and the cultural realm. In the artist’s work, Neumann believed, the archetypal forces of the psyche find symbolic expression, giving form to the deepest patterns of human experience.

Neumann developed these ideas in his book Art and the Creative Unconscious, a wide-ranging study of the psychological dimensions of art history. Drawing on examples from ancient cave paintings to modern abstract expressionism, Neumann explored the universal themes and motifs that recur across cultures and epochs.

At the heart of Neumann’s analysis is the concept of the “creative unconscious” – the primal source of artistic inspiration that lies beyond the individual ego. This unconscious, Neumann argued, is not a chaotic repository of repressed desires, but a purposive, autonomous force that seeks to manifest itself in the world. The artist’s task is to tap into this source, to open themselves up to its archetypal energies and give them concrete form.

Neumann identified several key stages in the creative process, paralleling the archetypal development of consciousness:

The Urge to Create: The initial impulse to make art, arising from the unconscious tension between inner and outer worlds. This is often experienced as a kind of “divine discontent,” a restless yearning to express something beyond words.

Inspiration: The sudden influx of archetypal images and ideas from the depths of the psyche. This is the “Aha!” moment of creative insight, the breakthrough that opens up new possibilities of expression.

Elaboration: The hard work of giving form to the inspired vision, of translating the archetypal into the particular. This requires both technical skill and emotional attunement, a delicate balance of conscious and unconscious.

Contemplation: The detached, reflective attitude that allows the artist to assess and refine their work. This “witnessing” perspective is crucial for integrating the creative experience and communicating it to others.

Release: The final letting go of the work, the offering of it to the world. This is a kind of sacrifice or “creative death,” a surrender of the ego’s attachment to the creation.

For Neumann, the artistic process is not just a personal quest, but a cultural necessity. In giving form to the archetypal forces of the collective unconscious, the artist helps to shape and transform the values of their society. Art is a kind of “dream of the culture,” a symbolic expression of its deepest hopes and fears, its myths and visions.

At the same time, Neumann recognized, the artist’s role is often a lonely and precarious one. To be a conduit for the creative unconscious is to risk being overwhelmed by its energies, to be alienated from the norms and conventions of one’s time. The artist must have a strong ego, a secure sense of self, to withstand the pressures of the unconscious and the misunderstandings of the world.

Ultimately, for Neumann, the artist’s journey is a spiritual one – a quest for meaning, wholeness, and transcendence. In embracing the creative unconscious, the artist opens themselves up to the numinous dimensions of reality, to the sacred that lies hidden within the ordinary. Art becomes a way of connecting with the divine, of participating in the ongoing creation of the world.

-

The Archetypal Stages of Development

One of Neumann’s most enduring contributions to depth psychology is his mapping of the archetypal stages of human development. Building on the work of Jung, Neumann proposed a universal sequence of psychological growth, from the primitive fusion of infancy to the mature integration of the self.

Neumann’s model is laid out in detail in The Origins and History of Consciousness and further elaborated in The Child. It posits a series of stages that unfold in a dialectical progression, with each new level transcending and including the previous ones. These stages are not rigid or linear, but represent general patterns of development that can overlap and recur throughout the lifespan.

The Uroboric Stage:

The primary, undifferentiated state of infancy, characterized by a fusion of self and world, subject and object. The psyche is dominated by the “central point,” the all-encompassing Great Mother archetype.

The Matriarchal Stage:

The emergence of the “primal relationship” between mother and child, which sets the stage for all future development. The ego begins to differentiate from the uroboric fusion, but remains embedded in the powerful field of the feminine archetype.

The Patriarchal Stage:

The rise of the masculine principle, as the ego asserts its independence and agency in the world. This stage is characterized by the “hero myth,” the struggle to free oneself from the grip of the unconscious and establish a sense of self.

The Filial Stage:

The reconciliation of masculine and feminine principles, as the ego learns to relate to the unconscious in a more balanced and integrated way. This stage involves a “return to the mother,” a reconnection with the archetypal feminine that was lost in the patriarchal stage.

The Centroversion Stage:

The reorientation of the ego towards the Self, the transpersonal center of the psyche. This stage marks the beginning of the individuation process proper, as the ego surrenders its centrality and aligns itself with the larger purposes of the Self.

The Universal Stage:

The culmination of the individuation process, in which the opposites are transcended and the self becomes a vessel for the transpersonal. This stage represents the realization of the “God within,” the fulfillment of human potential in a life of service and compassion.

For Neumann, these stages are not just a matter of individual development, but reflect the collective evolution of human consciousness. Each stage represents a new level of differentiation and integration, a new way of relating to self, world, and the divine. And each stage is shaped by the archetypal forces of the collective unconscious, the universal patterns that structure human experience.

At the same time, Neumann recognized, the process of development is rarely smooth or straightforward. Each stage brings with it new challenges and potential pitfalls, new opportunities for growth and regression. The transition from one stage to another can be marked by crisis and conflict, as old identities are shattered and new ones are forged.

Neumann placed particular emphasis on the pivotal role of the feminine archetype in this process. For him, the Great Mother was the primal matrix out of which all development arises, the nurturing ground of being that must be both embraced and transcended. The task of individuation, he argued, is not to reject the feminine, but to integrate it with the masculine in a higher synthesis.

This integration is symbolized by the archetype of the “sacred marriage,” the union of opposites that gives birth to the Self. In this marriage, the ego is not annihilated but transformed, purified of its attachments and opened to the transpersonal dimension. The result is a new kind of consciousness, a way of being in the world that is both fully human and divinely inspired.

-

Critique and Retrospective

Despite his seminal contributions to depth psychology, Neumann’s work has not been without its critics and detractors. Some have questioned the universality of his developmental model, arguing that it reflects a particular cultural and historical context rather than a timeless pattern. Others have challenged his tendency to gender the archetypes, seeing this as a reification of social stereotypes.

Feminist scholars, in particular, have taken issue with Neumann’s valorization of the “patriarchal” stage of development, arguing that it perpetuates a one-sided, masculine-dominated view of the psyche. They point out that Neumann’s model implicitly devalues the feminine, casting it as a regressive force to be overcome rather than an equal partner in the process of individuation.

Jungian thinkers like James Hillman have also pushed back against Neumann’s developmental approach, seeing it as too linear and teleological. For Hillman, the psyche is not a unitary entity that progresses through set stages, but a multiplicity of archetypal forces that co-exist in dynamic tension. The goal of analysis, in this view, is not to integrate the personality but to differentiate it, to give voice to the many “gods” within.

Hillman’s “polytheistic psychology” represents a significant departure from Neumann’s more hierarchical, developmental model. Where Neumann saw the psyche as a unified whole progressing towards a singular goal, Hillman emphasized the irreducible diversity of the archetypes, the need to honor the unique “calling” of each individual soul. For Hillman, the Self is not a fixed endpoint but an ongoing process of creative unfolding, a “making of soul” that embraces multiplicity and paradox.

Despite these critiques, however, Neumann’s work remains a rich and generative resource for depth psychology. His insights into the archetypal foundations of human experience, the dialectical nature of psychological growth, and the transformative power of the feminine continue to inspire and inform contemporary theory and practice.

In particular, Neumann’s emphasis on the importance of the “ego-Self axis” has had a lasting impact on Jungian thought. For Neumann, the key to individuation is not the dissolution of the ego but its alignment with the Self, the transpersonal center of the psyche. This alignment requires a delicate balance of agency and surrender, a willingness to actively engage the challenges of life while remaining open to the guidance of the unconscious.

Neumann’s understanding of the “centroversion” of libido, the gradual shift from ego-centeredness to Self-centeredness, also remains a powerful model for psychological growth. In contrast to Freud’s more reductive view of libido as a blind, instinctual force, Neumann saw it as a purposive, creative energy that seeks to manifest the deepest potentials of the individual and the collective.

Neumann’s work on the Great Mother archetype, while controversial, has also had a significant influence on feminist thought and practice. By highlighting the power and centrality of the feminine in human development, Neumann opened up new avenues for the exploration of women’s experience and the critique of patriarchal culture. His recognition of the dark, transformative aspect of the feminine, in particular, has resonated with many women seeking to reclaim the “wild woman” within.

Finally, Neumann’s vision of the artist as a mediator between the collective unconscious and the culture has continued to inspire depth psychological approaches to creativity and the arts. His understanding of art as a symbolic expression of archetypal forces, a way of giving form to the deepest patterns of human experience, remains a vital framework for the study of the creative process.

At the same time, the limitations and biases of Neumann’s work must also be acknowledged. His tendency to universalize a particular developmental model, his reliance on gendered archetypes, and his implicit privileging of the masculine all reflect the cultural and historical context in which he wrote. As depth psychology continues to evolve and diversify, it will be important to critically engage these aspects of Neumann’s thought while still honoring the depth and power of his insights.

In the end, perhaps the greatest legacy of Neumann’s work is the way it opens up the psyche to the transpersonal dimensions of human experience. By situating the individual within the larger context of the collective unconscious, the archetypal world, and the evolution of consciousness, Neumann helps us to see our personal struggles and triumphs as part of a greater unfolding. He reminds us that we are not alone on this journey of individuation, but are supported and guided by the deep structures of the psyche itself.

As we navigate the challenges and opportunities of our own time, Neumann’s vision of psychological growth and transformation remains a vital resource. His call to embrace the creative, generative power of the unconscious, to align ourselves with the Self and its larger purposes, is as relevant today as it was in his own time. By engaging his work critically and imaginatively, we can continue to deepen our understanding of the archetypal foundations of human experience and to chart new pathways for the unfolding of the soul.

-

Legacy

The work of Erich Neumann represents a profound and far-reaching exploration of the archetypal dimensions of the human psyche. Building on the pioneering insights of Jung, Neumann mapped the deep structures and dynamics of psychological development, from the primitive fusion of the uroboros to the mature integration of the Self.

At the heart of Neumann’s vision is a recognition of the transpersonal forces that shape and guide human life. For Neumann, the psyche is not a isolated entity but a microcosm of the larger universe, a reflection of the archetypal patterns that underlie all of existence. By aligning ourselves with these patterns, by embracing the creative power of the unconscious, we can tap into a source of meaning and purpose that transcends the individual ego.

Neumann’s understanding of the Great Mother archetype, in particular, remains a powerful and provocative contribution to depth psychology. By exploring the role of the feminine in human development, Neumann opened up new avenues for the study of women’s experience and the critique of patriarchal culture. His recognition of the transformative, regenerative power of the feminine principle continues to inspire feminist thought and practice today.

At the same time, Neumann’s work is not without its limitations and blind spots. His reliance on gendered archetypes, his tendency to universalize a particular developmental model, and his implicit privileging of the masculine all reflect the cultural and historical context in which he wrote. As depth psychology continues to evolve and diversify, it will be important to critically engage these aspects of Neumann’s thought while still honoring the richness and complexity of his insights.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of Neumann’s work is the way it situates the individual within the larger context of the collective unconscious and the evolution of human consciousness. For Neumann, the journey of individuation is not just a personal quest but a participation in a cosmic unfolding, a creative process that encompasses all of life. By aligning ourselves with this process, by embracing the archetypal forces that guide and shape us, we can discover a sense of meaning and purpose that transcends the narrow confines of the ego.

As we navigate the challenges and opportunities of our own time, Neumann’s vision of psychological growth and transformation remains a vital resource. His call to honor the creative power of the unconscious, to embrace the feminine principle, and to align ourselves with the Self and its larger purposes is as relevant today as it was in his own time. By engaging his work critically and imaginatively, we can continue to deepen our understanding of the archetypal foundations of human experience and to chart new pathways for the unfolding of the soul.

In the end, the work of Erich Neumann stands as a testament to the enduring power and mystery of the human psyche. By illuminating the deep structures and dynamics that shape our inner lives, Neumann helps us to see ourselves as part of a larger whole, a cosmic web of meaning and purpose. His insights continue to inspire and challenge us, inviting us to embrace the full complexity and potential of the soul. As we move forward into an uncertain future, may we draw on the wisdom and vision of this great pioneer of depth psychology, and may we find the courage and creativity to chart our own paths of individuation and transformation.

In retrospect, while Neumann’s work has been highly influential in the field of depth psychology, it is important to recognize that some of his ideas have been challenged, modified, or discarded over time. This is particularly true in light of the later work of James Hillman, who developed his own unique approach to archetypal psychology that departed in significant ways from Neumann’s theories.

One of the key areas where Hillman differed from Neumann was in his understanding of the nature of archetypes. While Neumann tended to view archetypes as universal, predetermined structures that shape human development in a linear fashion, Hillman saw them as fluid, dynamic, and multivalent. For Hillman, archetypes were not fixed entities but living presences that could manifest in a wide variety of ways depending on the individual and the cultural context.

Hillman also challenged Neumann’s tendency to gender the archetypes, arguing that this approach was too simplistic and reductive. Instead, Hillman emphasized the importance of recognizing the complex, multifaceted nature of archetypal energies, which could not be easily categorized as masculine or feminine. He argued that the goal of individuation was not to integrate these opposites but to cultivate a more fluid, flexible relationship to the various aspects of the psyche.

Another area where Hillman departed from Neumann was in his understanding of the role of the ego in psychological development. While Neumann emphasized the importance of strengthening and integrating the ego in order to navigate the challenges of individuation, Hillman saw the ego as just one of many “voices” within the psyche. For Hillman, the goal was not to build a strong, unified ego but to cultivate a more dialogical, imaginative relationship to the various parts of the self.

Hillman’s approach also placed greater emphasis on the importance of creativity, imagination, and aesthetic experience in the process of individuation. While Neumann recognized the significance of art and creativity, Hillman made them central to his understanding of psychological growth. For Hillman, engaging with images, stories, and symbols was not just a means of expressing archetypal energies but a way of actively shaping and transforming them.

Despite these differences, however, it is important to recognize the enduring influence of Neumann’s work on the field of depth psychology. His insights into the archetypal foundations of human experience, the role of the feminine in psychological development, and the importance of integrating the personal and collective dimensions of the psyche continue to inspire and inform contemporary theory and practice.

Moreover, while some of Neumann’s specific ideas may have been challenged or modified over time, his larger vision of the psyche as a living, dynamic reality that is shaped by transpersonal forces remains a vital contribution to depth psychology. By situating the individual within the larger context of the collective unconscious and the evolution of human consciousness, Neumann helped to open up new avenues for understanding the mysteries of the soul.

As we continue to grapple with the challenges and opportunities of our own time, the work of Erich Neumann remains a rich and generative resource for depth psychology. By engaging with his ideas critically and imaginatively, we can continue to deepen our understanding of the archetypal dimensions of human experience and to chart new pathways for psychological growth and transformation. At the same time, we must also be willing to question and revise his theories in light of new insights and perspectives, recognizing that the field of depth psychology is always evolving and expanding.

In the end, perhaps the greatest legacy of Neumann’s work is the way it invites us to engage with the living, dynamic reality of the psyche. By illuminating the deep structures and patterns that shape our inner lives, Neumann challenges us to become more aware of the archetypal forces that guide and shape us. He encourages us to cultivate a more conscious, creative relationship to the unconscious, recognizing that it is not just a source of conflict and struggle but also a wellspring of meaning, purpose, and transformation.

If you liked this read the articles on other Jungian topics:

Bibliography:

- Neumann, Erich. The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press, 1954.

- Neumann, Erich. The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype. Princeton University Press, 1955.

- Neumann, Erich. Art and the Creative Unconscious: Four Essays. Princeton University Press, 1959.

- Neumann, Erich. The Child: Structure and Dynamics of the Nascent Personality. Putnam, 1973.

- Jung, Carl. Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Princeton University Press, 1953-1979.

- Hillman, James. Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row, 1975.

- Hillman, James. The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. Random House, 1996.

- Hillman, James. The Force of Character and the Lasting Life. Ballantine Books, 1999.

- Roszak, Theodore, Mary E. Gomes, and Allen D. Kanner, editors. Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind. Sierra

- Club Books, 1995.

- Kalsched, Donald. The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit. Routledge, 1996.

- Stein, Murray, editor. Jungian Analysis. Open Court, 1982.

- Edinger, Edward. Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Shambhala, 1992.

- Samuels, Andrew. Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge, 1985.

- Bly, Robert. Iron John: A Book About Men. Addison-Wesley, 1990.

- Zweig, Connie, and Abrams, Jeremiah, editors. Meeting the Shadow: The Hidden Power of the Dark Side of Human Nature.

- Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1991.

Further Reading:

- Neumann, Erich. The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press, 1954.

- Neumann, Erich. The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype. Princeton University Press, 1955.

- Neumann, Erich. Art and the Creative Unconscious: Four Essays. Princeton University Press, 1959.

- Neumann, Erich. The Child: Structure and Dynamics of the Nascent Personality. Putnam, 1973.

- Hillman, James. Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row, 1975.

- Hillman, James. The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. Random House, 1996.

- Hillman, James. The Force of Character and the Lasting Life. Ballantine Books, 1999.

- Hillman, James. Archetypal Psychology. Spring Publications, 1983.

- Roszak, Theodore, Mary E. Gomes, and Allen D. Kanner, editors. Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind. Sierra

- Club Books, 1995.

- Kalsched, Donald. The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit. Routledge, 1996.

- Stein, Murray, editor. Jungian Analysis. Open Court, 1982.

- Edinger, Edward. Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Shambhala, 1992.

- Samuels, Andrew. Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge, 1985.

- Bly, Robert. Iron John: A Book About Men. Addison-Wesley, 1990.

- Zweig, Connie, and Abrams, Jeremiah, editors. Meeting the Shadow: The Hidden Power of the Dark Side of Human Nature.

- Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1991.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

0 Comments