The Depth Psychology o Kabbalistic Concept of Ein Sof

What is Kabbalah?

Kabbalah is a mystical tradition within Judaism that seeks to understand the nature of divinity, the structure of the universe, and the purpose of human existence. The term “Kabbalah” comes from the Hebrew root “k-b-l,” which means “to receive” or “to accept,” referring to the reception of divine wisdom and the acceptance of spiritual practices.

Kabbalah emerged in 12th century Provence and Spain, drawing on earlier forms of Jewish mysticism such as Merkavah mysticism and the Bahir. It developed and flourished in the medieval period, particularly with the publication of the Zohar in the 13th century. The Zohar, a mystical commentary on the Torah, remains one of the most influential and widely studied Kabbalistic texts.

At the heart of Kabbalah is the idea that the divine realm is both transcendent and immanent—that God is both the source of all creation and intimately interwoven with it. Kabbalists seek to understand the relationship between the infinite (Ein Sof) and the finite, between the unity of God and the multiplicity of creation.

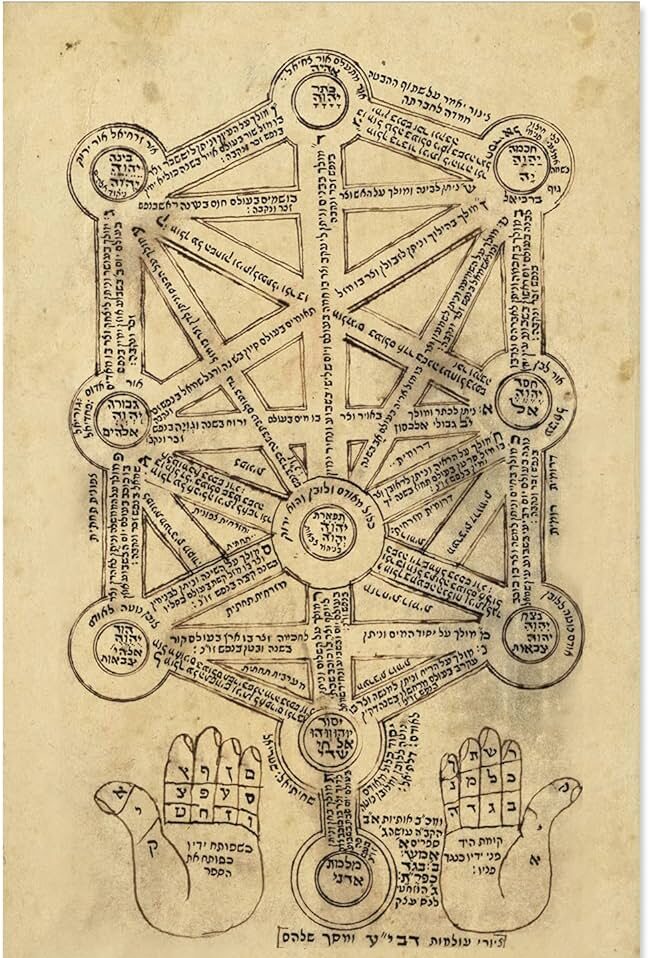

One of the central symbols of Kabbalah is the Tree of Life, a diagram representing the ten Sefirot or emanations of divine energy. The Sefirot are the archetypal qualities or attributes through which the infinite expresses itself in the finite world. They are often depicted as interconnected spheres, forming a kind of cosmic map of creation.

Kabbalists believe that by meditating on the Sefirot and aligning oneself with their energies, one can awaken to the divine presence within and participate more fully in the unfolding of creation. Kabbalah thus offers not only a theoretical framework for understanding the cosmos but a practical path of spiritual transformation.

Another key concept in Kabbalah is that of Tikkun Olam, the repair or healing of the world. According to Lurianic Kabbalah, the process of creation involved a cosmic shattering (Shevirat HaKelim) in which the divine light was too powerful for the vessels of the Sefirot to contain. The shards of these broken vessels fell into the material world, trapping sparks of divine light. The task of humanity, then, is to engage in acts of love and kindness to free these trapped sparks and restore the world to its original wholeness.

Kabbalah has had a profound influence on Jewish thought and practice, shaping ideas about prayer, ritual, and the interpretation of scripture. It has also had a significant impact on Western esotericism, inspiring movements such as Hermeticism, Rosicrucianism, and the Golden Dawn.

In the 20th century, Kabbalah gained renewed interest among scholars and spiritual seekers, both within and beyond the Jewish community. The works of Gershom Scholem, a pioneering scholar of Jewish mysticism, helped to bring Kabbalah into the mainstream of academic study. More recently, the Kabbalah Centre, founded by Philip Berg, has popularized a contemporary form of Kabbalah that draws on traditional sources but adapts them for a modern audience.

Today, Kabbalah continues to attract individuals seeking a deeper understanding of the mysteries of existence and a path of personal and collective transformation. Its rich symbolism, profound insights, and practical teachings offer a powerful framework for exploring the nature of self, God, and cosmos in an age of rapid change and uncertainty.

Whether approached as a scholarly discipline, a spiritual practice, or a source of wisdom for daily life, Kabbalah remains a vital and dynamic tradition—one that invites us to engage with the deepest questions of meaning and purpose and to participate in the ongoing unfolding of creation.

What is Ein Sof?

The concept of Ein Sof is a central tenet in the mystical tradition of Kabbalah. Ein Sof, which literally means “without end” or “the infinite,” refers to the unknowable and boundless aspect of God that exists beyond all forms and distinctions. It points to the ultimate ground of being from which all of creation emerges and to which it ultimately returns.

For Kabbalists, Ein Sof is not a static entity but a dynamic process—the ever-unfolding creative power that sustains the universe. It is the source of all life, the wellspring of divine energy that flows through the intricate web of existence. To speak of Ein Sof, then, is to speak of the sacred mystery at the heart of reality—the ineffable oneness that underlies the multiplicity of forms.

Ein Sof is the infinite, boundless, and unknowable aspect of God that exists beyond all limitations and distinctions. It is the source and ground of all being, the ultimate reality from which all of creation emerges.

For Kabbalists, Ein Sof is not a static entity or a distant, transcendent God, but rather a dynamic and ever-unfolding process. It is the constant flow of divine energy that sustains the universe and gives life to all things. Ein Sof is not separate from the world but intimately interwoven with it, permeating every aspect of existence.

One of the key ideas associated with Ein Sof is that it is beyond all names, descriptions, or attributes. It is the nameless and formless ground of being that cannot be grasped by the human mind or expressed in language. Any attempt to define or limit Ein Sof is seen as a form of idolatry, a reduction of the infinite to the finite.

At the same time, Kabbalists believe that Ein Sof is not entirely inaccessible or unknowable. While the essence of Ein Sof remains hidden, its presence can be experienced and known through its manifestations in the world. The Kabbalists use the term “Ohr Ein Sof,” or the “Light of the Infinite,” to describe the divine energy that flows from Ein Sof and gives life to all things.

According to Kabbalistic thought, the process of creation involves a series of emanations or “Sephirot” that channel the light of Ein Sof into the world. These Sephirot are the divine attributes or archetypes that structure the universe and give it meaning. They are often depicted as a tree of life, with each Sephirah representing a different aspect of God’s creative power.

The Kabbalists believe that the purpose of human life is to ascend the tree of life and unite with the divine source. This involves a process of spiritual growth and transformation, as one learns to align oneself with the divine attributes and channel the light of Ein Sof into the world. By doing so, one can participate in the ongoing process of creation and help to repair the world (tikkun olam).

One of the central paradoxes of Ein Sof is that it is both transcendent and immanent, both beyond the world and within it. This idea is expressed in the Kabbalistic concept of “tzimtzum,” or contraction. According to this idea, Ein Sof contracted or withdrew itself in order to make space for the world to exist. This self-limitation of the infinite is seen as an act of love and generosity, a willingness to make room for otherness and multiplicity.

At the same time, the Kabbalists believe that Ein Sof remains present within the world, animating it from within. The divine spark is hidden within every creature and every particle of matter, waiting to be revealed and reunited with its source. The task of the spiritual seeker is to uncover this hidden spark and reconnect with the infinite.

The concept of Ein Sof has profound implications for how we understand the nature of reality and our place within it. It suggests that the universe is not a static or mechanistic system, but a living and dynamic process of divine unfolding. It challenges us to see the world not as a collection of separate objects, but as a web of interconnected relationships, all part of a greater whole.

At the same time, the idea of Ein Sof reminds us of the ultimate mystery and unknowability of existence. It invites us to approach the world with humility and wonder, recognizing that our understanding is always partial and provisional. It calls us to live with a sense of openness and receptivity, attuned to the infinite possibilities of each moment.

Ultimately, the concept of Ein Sof points us towards a deep spiritual truth: that the ground of all being is a dynamic and creative process of love and generosity. It suggests that the universe is not indifferent or hostile to our existence, but is ultimately on our side, supporting our growth and transformation. By aligning ourselves with this divine unfolding, we can discover our true nature and purpose, and participate in the great work of healing and transformation.

God as Verb

One of the key insights of Kabbalah is that divinity is not a noun but a verb—not a static being but a dynamic becoming. Ein Sof points to this fluid, ever-emerging quality of the sacred. It suggests that God is not a distant, transcendent figure but the immanent aliveness that permeates all things.

In this view, the divine is not separate from the world but intimately interwoven with it. As the Kabbalists put it, “There is no place empty of God.” The world is not a lifeless mechanism but a living expression of divine creativity, a constant unfolding of Ein Sof into myriad forms.

This notion of God as verb resonates with process theology and other contemporary spiritual philosophies that emphasize the evolving, relational nature of reality. It challenges the traditional Western view of a static, unchanging God and invites us to see the sacred as a dynamic presence that is always in motion, always creating anew.

The Tree of Life

Central to Kabbalistic thought is the symbol of the Tree of Life—a diagram representing the ten Sefirot, or emanations of Ein Sof. The Sefirot are the archetypal qualities or powers through which the infinite expresses itself in the finite world. They are often depicted as interconnected spheres arranged in three columns, forming a sort of cosmic map of creation.

The Tree of Life is not a literal description of the universe but a symbolic framework for understanding the unfolding of divine energy. Each Sefirah represents a different facet of God’s creative power, from the crown of pure consciousness (Keter) to the foundation of the physical world (Malkhut). Together, they form a holographic matrix in which each part contains the whole.

For Kabbalists, the Tree of Life is not just a theoretical construct but a living reality to be experienced and embodied. By meditating on the Sefirot and aligning oneself with their energies, one can awaken to the divine presence within and participate more fully in the unfolding of creation. The Tree becomes a map for the journey of the soul, a guidemap for actualizing one’s highest potential.

Tzimtzum and the Breaking of the Vessels

A key concept in Lurianic Kabbalah is that of Tzimtzum—the notion that Ein Sof withdrew itself in order to make room for creation. According to this idea, the infinite contracted itself, creating a void in which the finite world could emerge. This primal act of self-limitation is seen as an expression of divine love, a willingness to make space for otherness.

Related to Tzimtzum is the idea of Shevirat HaKelim, the “breaking of the vessels.” As Ein Sof emanated into the Sefirot, the light was too powerful for the vessels to contain, causing them to shatter. The shards of these broken vessels fell into the material world, trapping sparks of divine light.

For the Kabbalists, this cosmic shattering is the origin of evil and suffering in the world. The task of humanity, then, is to engage in Tikkun Olam, the repair of the world, by freeing the trapped sparks and reuniting them with their divine source. This is done through ethical living, spiritual practice, and acts of loving-kindness.

These mythopoetic images of Tzimtzum and the Breaking of the Vessels speak to the paradox of existence—the play of light and shadow, wholeness and brokenness, that characterizes the human condition. They suggest that the world is not a finished product but a work in progress, an evolving tapestry in which we all have a threads to weave.

Connections to Depth Psychology and Jungian Thought

The Kabbalistic understanding of Ein Sof and the unfolding of creation has fascinating parallels with depth psychology and Jungian thought. Like the Kabbalists, Jung saw the psyche as a dynamic, self-organizing system that is constantly evolving towards greater wholeness. He understood the unconscious not just as a repository of repressed contents but as a creative matrix from which new forms of consciousness emerge.

Jung’s concept of the Self—the integrating center of the psyche that transcends the ego—resonates with the Kabbalistic notion of Ein Sof as the ultimate ground of being. Both point to a transpersonal dimension of the psyche that is the source of wisdom, healing, and transformation.

The Kabbalistic idea of the Sefirot also has intriguing connections to Jung’s theory of archetypes. Just as the Sefirot are the archetypal qualities through which Ein Sof expresses itself, Jung saw the archetypes as universal patterns that structure the psyche and give rise to symbolic images. Both suggest a deep underlying order to the cosmos, a network of meaning that we can tap into for guidance and growth.

Moreover, the Kabbalistic understanding of evil as the result of a cosmic shattering has parallels with Jung’s notion of the shadow. For Jung, the shadow represents the disowned and unintegrated aspects of the psyche that we project onto others. By recognizing and reclaiming these split-off parts of ourselves, we can engage in the work of psychological repair—a process not unlike the Kabbalistic Tikkun.

Finally, the Kabbalistic emphasis on the transformative power of language and symbol resonates with Jung’s approach to dream work and active imagination. For both, engaging with symbolic images is a way of bridging conscious and unconscious, accessing deeper layers of meaning and potential. By meditating on the Sefirot or dialoguing with dream figures, we can align ourselves with the creative energies of the psyche and participate in the unfolding of our own individuation.

Lessons from the Kabbalah

The Kabbalistic concept of Ein Sof offers a rich and evocative framework for understanding the nature of divinity, the structure of the cosmos, and the journey of the soul. It invites us to see God not as a static being but as a dynamic becoming—the ever-flowing source of life that sustains the world.

By contemplating the Tree of Life and engaging with the Sefirot, we can awaken to the divine presence within and align ourselves with the creative energies of the universe. We can recognize our own brokenness as part of a larger cosmic story, and participate in the work of Tikkun—the healing and repair of the world.

At the same time, the Kabbalistic worldview has profound resonances with depth psychology and Jungian thought. Both recognize the psyche as a living, evolving system that is constantly unfolding towards greater wholeness. Both see the individual as a microcosm of the cosmos, a holographic expression of deeper archetypal patterns.

By bringing these two streams of wisdom together, we can access a more integrative understanding of the human condition—one that honors the mysteries of the soul and the sacredness of the world. We can engage in the work of transformation not as a solitary quest but as part of a larger cosmic drama, a grand adventure of awakening and return.

Ultimately, the Ein Sof points us back to the ineffable oneness at the heart of existence—the nameless mystery from which we come and to which we shall return. By opening ourselves to this mystery, we can touch the infinite within the finite, the eternal within the everyday. We can awaken to the divine spark that animates all things, and know ourselves as part of a greater Whole.

In this time of global crisis and transformation, such an integral vision is more needed than ever. May the wisdom of Kabbalah and depth psychology guide us on the path of healing and wholeness, as we work to co-create a world that reflects the love and light of the Ein Sof.

Bibliography:

Drob, S. L. (2000). Kabbalistic Metaphors: Jewish Mystical Themes in Ancient and Modern Thought. Jason Aronson.

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Putnam.

Gikatilla, J. (1994). Gates of Light: Sha’are Orah. HarperOne.

Green, A. (2004). A Guide to the Zohar. Stanford University Press.

Halevi, Z. (1979). Kabbalah: Tradition of Hidden Knowledge. Thames & Hudson.

Scholem, G. (1974). Kabbalah. Meridian.

Jung, C. G. (1968). Psychology and Alchemy. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1976). The Symbolic Life: Miscellaneous Writings. Princeton University Press.

Luria, I. (2005). The Tree of Life: Chayyim Vital’s Introduction to the Kabbalah of Isaac Luria. The Kabbalah Centre.

Matt, D. C. (1996). The Essential Kabbalah: The Heart of Jewish Mysticism. HarperOne.

Mopsik, C. (1993). Les grands textes de la cabale: les rites qui font Dieu. Verdier.

Scholem, G. (1965). On the Kabbalah and its Symbolism. Schocken Books.

Schwartz, H. (2000). Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford University Press.

Sperling, H., & Simon, M. (1931). The Zohar. The Soncino Press.

Winkler, G. (1997). Magic of the Ordinary: Recovering the Shamanic in Judaism. North Atlantic Books.

Further Reading:

Abrams, D. (1994). The Book Bahir: An Edition Based on the Earliest Manuscripts. Cherub Press.

Bonder, N. (1999). The Kabbalah of Envy: Transforming Hatred, Anger, and Other Negative Emotions. Shambhala.

Buber, M. (1991). Tales of the Hasidim. Schocken Books.

Corbin, H. (1998). Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabi. Princeton University Press.

Dan, J. (2006). Kabbalah: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Elior, R. (2007). Jewish Mysticism: The Infinite Expression of Freedom. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization.

Fine, L. (2003). Physician of the Soul, Healer of the Cosmos: Isaac Luria and His Kabbalistic Fellowship. Stanford University Press.

Fortune, D. (2000). The Mystical Qabalah. Weiser Books.

Frankiel, T. (1993). The Gift of Kabbalah: Discovering the Secrets of Heaven, Renewing Your Life on Earth. Jewish Lights Publishing.

Green, A. (1992). Seek My Face, Speak My Name: A Contemporary Jewish Theology. Jason Aronson.

Hoffman, E. (1996). The Way of Splendor: Jewish Mysticism and Modern Psychology. Rowman & Littlefield.

Idel, M. (1988). Kabbalah: New Perspectives. Yale University Press.

Jacobs, L. (1999). A Jewish Theology. Behrman House.

Kaplan, A. (1990). Inner Space: Introduction to Kabbalah, Meditation and Prophecy. Moznaim Publishing Corporation.

McGlynn, P. (1999). The Essentials of Jewish Mysticism. Oneworld Publications.

Schachter-Shalomi, Z., & Miles-Yepez, N. (2009). A Heart Afire: Stories and Teachings of the Early Hasidic Masters. Jewish Publication Society.

Scholem, G. (1970). Origins of the Kabbalah. Jewish Publication Society.

Scholem, G. (1991). On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead: Basic Concepts in the Kabbalah. Schocken Books.

Unterman, A. (2008). The Kabbalistic Tradition: An Anthology of Jewish Mysticism. Penguin Classics.

Wolfson, E. R. (1995). Circle in the Square: Studies in the Use of Gender in Kabbalistic Symbolism. State University of New York Press.

Wolinsky, S. (1999). Quantum Consciousness: The Guide to Experiencing Quantum Psychology. Bramble Books.

Influences on Jung

0 Comments