In the landscape of Western philosophy, few figures cast as long a shadow over the practice of psychotherapy as Søren Kierkegaard. Writing from his native Copenhagen in the mid-nineteenth century, this Danish philosopher articulated a vision of human existence so penetrating, so attuned to the agonies and ecstasies of individual subjectivity, that his influence would eventually permeate the consulting rooms of therapists more than a century after his death. To understand contemporary existential psychotherapy is to grapple with Kierkegaard’s profound insights into anxiety, despair, authenticity, and the terrible freedom that defines human consciousness.

Kierkegaard stands as the acknowledged father of existentialism, though he died decades before the movement would receive its name. His radical focus on the individual’s subjective experience, his unflinching examination of human suffering, and his insistence that truth is found not in abstract systems but in passionate, committed engagement with one’s own existence established the philosophical foundation upon which later existentialists would build. Where his philosophical predecessors constructed grand systematic edifices, Kierkegaard turned inward, asking what it means to be a self, how one becomes who one truly is, and why this process involves such profound anguish.

The Birth of Existential Thought

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy identifies Kierkegaard as existentialism’s originating voice because he placed the existing individual at the center of philosophical inquiry in a way that was revolutionary for his time. The Hegelian system that dominated European philosophy in Kierkegaard’s era sought to comprehend all reality within a totalizing rational framework, but Kierkegaard rebelled against this abstraction with fierce conviction. He insisted that existence precedes essence, that we do not discover our nature through contemplation of universal categories but through the choices we make in the concrete particularity of our lives.

This emphasis on individual existence, on the irreducible subjectivity of lived experience, resonates throughout Kierkegaard’s vast corpus. In works like “The Concept of Anxiety” and “The Sickness Unto Death,” he conducted what might be called a phenomenological investigation of human consciousness before phenomenology existed as a formal discipline. He examined the structures of human existence from the inside, describing with exquisite precision the various modes of despair, the vertiginous experience of freedom, and the anxiety that accompanies authentic self-becoming.

What makes Kierkegaard’s thought particularly relevant to psychotherapy is his recognition that human suffering is not primarily a problem to be solved through rational analysis but an existential condition to be understood, confronted, and transformed through how we relate to it. He understood that anxiety and despair are not aberrations but fundamental aspects of human existence that reveal something essential about our nature as self-conscious beings capable of reflection and choice.

The Architecture of Anxiety

Kierkegaard’s analysis of anxiety in “The Concept of Anxiety” remains one of the most profound contributions to understanding this ubiquitous human experience. Unlike fear, which has a specific object, anxiety arises from our confrontation with possibility itself. We experience anxiety, Kierkegaard argued, because we are free, because the future remains undetermined, because we must choose who we will become without any guarantee that our choices are correct. This “dizziness of freedom,” as he called it, is the price we pay for being the kind of creatures who can imagine alternative futures and bear responsibility for bringing one of those futures into being.

The therapeutic implications of this insight are profound. Rather than viewing anxiety as a disorder to be eliminated, Kierkegaard invites us to recognize it as a signal of our freedom and our responsibility for self-creation. Contemporary therapists working from existential frameworks understand that attempting to eliminate anxiety entirely would be tantamount to denying our fundamental nature as free beings. Instead, therapy becomes a process of helping clients develop a different relationship with their anxiety, recognizing it as an indicator that they stand before significant choices about how to live.

The American Psychological Association’s resources on existential therapy acknowledge this Kierkegaardian insight, noting that existential approaches help clients confront the anxiety inherent in authentic existence rather than defending against it through various forms of bad faith. This perspective has influenced countless therapeutic modalities, from existential-humanistic therapy to contemporary approaches that integrate existential themes with other frameworks.

Despair and the Dialectic of Self-Becoming

In “The Sickness Unto Death,” Kierkegaard presented an even more intricate analysis of human suffering through his examination of despair. He understood despair not as simple sadness but as a fundamental misrelation in the structure of selfhood itself. The self, for Kierkegaard, is not a stable substance but a relation that relates itself to itself, a dynamic synthesis of finite and infinite, temporal and eternal, necessity and possibility. Despair occurs when this synthesis becomes unbalanced, when we over-identify with one pole at the expense of the other.

Kierkegaard described multiple forms of despair with the precision of a clinician. There is the despair of infinitude, where we lose ourselves in fantastic possibilities and never commit to any concrete actuality. There is the despair of finitude, where we become so absorbed in worldly concerns that we forget the eternal dimension of selfhood. There is the despair of necessity, where we believe we have no freedom to change, and the despair of possibility, where everything seems possible but nothing becomes actual. Most insidious is what Kierkegaard called the despair of defiance, where we attempt to create ourselves entirely on our own terms, refusing to acknowledge the conditions and limitations that define human existence.

This phenomenology of despair has proven remarkably useful for psychotherapists attempting to understand the varied ways human beings suffer. Irvin Yalom, perhaps the most influential contemporary existential therapist, drew heavily on Kierkegaard’s insights in developing his approach to existential psychotherapy. Yalom’s identification of the “givens of existence” that humans must confront—death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness—echoes Kierkegaard’s concern with how we respond to the fundamental conditions of human life.

The Three Spheres of Existence

Kierkegaard’s description of three stages or spheres of existence provides another framework that has proven valuable for understanding psychological development and therapeutic process. The aesthetic stage is characterized by the pursuit of immediate pleasure and the avoidance of boredom. The aesthetic individual lives in the moment, seeking novelty and sensation, but ultimately finds this mode of existence empty because it lacks continuity and depth. The aesthetic life, for all its apparent freedom, becomes a form of bondage to external stimulation and the opinions of others.

The ethical stage represents a movement toward commitment, responsibility, and the development of character through sustained engagement with social roles and moral obligations. The ethical individual chooses to be bound by universal principles and finds meaning through fulfilling duties and maintaining relationships. Yet Kierkegaard recognized that the ethical life, too, has its limitations. It can become rule-bound, legalistic, and ultimately fail to address the deepest questions of individual existence and our relationship with the transcendent.

The religious stage, in Kierkegaard’s framework, represents the highest form of existence, where the individual stands in direct relation to the absolute through faith. This is not faith as intellectual assent to propositions but faith as passionate commitment in the face of uncertainty, what Kierkegaard called the “leap of faith.” The religious individual accepts the paradoxes of existence and finds meaning not through rational comprehension but through surrender to something beyond rational understanding.

While Kierkegaard’s religious framework may not translate directly into secular therapeutic contexts, the developmental trajectory he describes resonates with many therapeutic processes. Clients often enter therapy operating primarily in the aesthetic mode, seeking to avoid pain and maximize pleasure. Therapy may help them develop ethical commitments and the capacity for sustained relationships. For some, the therapeutic journey culminates in what might be called spiritual transformation, a fundamental reorientation of their relationship to existence itself.

Kierkegaard and the Emergence of Existential Psychotherapy

The influence of Kierkegaard on psychotherapy did not occur immediately. His work had to first percolate through the European intellectual tradition, influencing philosophers and theologians who would later inspire the development of existential thought in the twentieth century. Martin Heidegger, whose “Being and Time” stands as one of the monuments of existential philosophy, acknowledged his debt to Kierkegaard’s analysis of anxiety and temporality. Jean-Paul Sartre developed Kierkegaard’s insights about freedom and responsibility into a comprehensive existential philosophy, though Sartre’s atheistic conclusions diverged sharply from Kierkegaard’s Christian commitments.

The Swiss psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger pioneered the application of existential philosophy to psychiatric practice in the early twentieth century, drawing on both Kierkegaard and Heidegger to develop what he called Daseinsanalysis. Binswanger recognized that psychiatric symptoms could not be adequately understood through the mechanistic frameworks of biological psychiatry alone but required attention to the patient’s subjective experience and their way of being-in-the-world.

Viktor Frankl, a Holocaust survivor and founder of logotherapy, extended Kierkegaard’s insights about meaning and suffering into a therapeutic approach that emphasized the human capacity to find meaning even in the most horrific circumstances. Frankl’s assertion that meaning can be discovered through suffering echoes Kierkegaard’s view that anxiety and despair, properly confronted, can become transformative rather than simply destructive.

Irvin Yalom synthesized these various strands of existential thought in his influential work “Existential Psychotherapy,” published in 1980. Yalom’s approach makes Kierkegaard’s insights clinically accessible, showing how therapists can help clients confront the existential givens of human existence with greater awareness and authenticity. The Existential Therapy Institute continues to train therapists in these approaches, emphasizing the Kierkegaardian themes of anxiety, freedom, and authentic self-becoming.

Rollo May, another giant of existential psychology in America, brought Kierkegaard’s concepts into dialogue with depth psychology and psychoanalysis. May’s work on anxiety, creativity, and the courage to be draws deeply from Kierkegaardian sources while making these ideas relevant to mid-twentieth-century American culture. His book “The Meaning of Anxiety” directly engages with Kierkegaard’s analysis while exploring anxiety’s role in both psychopathology and creative self-expression.

Contemporary Applications and Therapeutic Modalities

The influence of Kierkegaard extends far beyond therapists who explicitly identify as existential. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a contemporary evidence-based approach, incorporates existential themes about values, commitment, and psychological flexibility that resonate with Kierkegaard’s emphasis on passionate engagement with life. The emphasis in ACT on accepting difficult emotions rather than struggling against them parallels Kierkegaard’s insight that anxiety and despair must be confronted rather than avoided.

Narrative therapy, developed by Michael White and David Epston, shares Kierkegaard’s concern with how we construct meaning through the stories we tell about our lives. The narrative therapy emphasis on re-authoring one’s life story to align with one’s values echoes Kierkegaard’s insistence that we become who we are through the choices we make and the commitments we sustain.

Even psychoanalysis, despite its different theoretical origins, has been enriched by existential insights. Existential psychoanalysts like Erich Fromm integrated Kierkegaard’s concerns with freedom and authenticity into psychoanalytic frameworks. More recently, relational psychoanalysis has explored themes of intersubjectivity and mutual recognition that resonate with Kierkegaard’s understanding of the self as fundamentally relational.

Contemporary existential therapists continue to draw on Kierkegaard’s work in diverse ways. Emmy van Deurzen, a leading British existential therapist, has developed approaches that help clients examine their assumptions about existence across different dimensions of human life. Kirk Schneider, president of the Existential-Humanistic Institute, integrates Kierkegaardian themes with humanistic psychology’s emphasis on growth and self-actualization.

The Mystical Dimension: Kierkegaard, Simone Weil, and the Apophatic Tradition

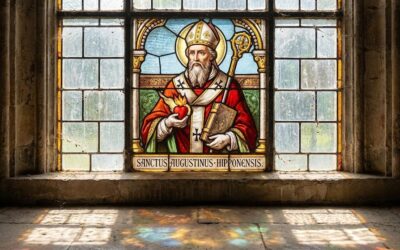

To fully appreciate Kierkegaard’s significance, we must recognize his place within the broader tradition of Christian mysticism and apophatic theology. While Kierkegaard was primarily a philosopher rather than a systematic theologian, his work shares profound affinities with the mystical tradition’s emphasis on direct experience of the divine, the limitations of rational comprehension, and the transformation of the self through suffering.

Simone Weil, the French philosopher and mystic who lived a century after Kierkegaard, developed themes remarkably parallel to his insights. Weil’s concept of “decreation”—the process of undoing the illusion of separate selfhood to allow reality to fill us—resonates with Kierkegaard’s understanding that the self must be surrendered in faith. Her notion of “affliction” as a particular kind of suffering that forces us to confront the truth of our condition parallels Kierkegaard’s analysis of despair as potentially transformative when properly understood.

Both Kierkegaard and Weil emphasized waiting and attention as spiritual practices. Weil wrote that “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity,” while Kierkegaard understood that authentic faith requires patient openness to transcendence rather than attempts to grasp or control it. Both recognized that the ego’s incessant demands must be quieted for genuine transformation to occur.

The desert fathers and mothers of early Christianity, mystics like Meister Eckhart, and later figures in the apophatic tradition all share Kierkegaard’s conviction that ultimate reality cannot be captured in concepts but must be approached through paradox, negation, and the surrender of our familiar ways of knowing. St. John of the Cross, with his concept of the dark night of the soul, described a process of spiritual transformation through suffering that prefigures Kierkegaard’s understanding of how despair can become the gateway to authentic selfhood.

These connections matter for psychotherapy because they remind us that Kierkegaard’s insights emerge from a profound spiritual tradition concerned with human transformation. While secular therapists may translate his religious language into psychological terms, something essential may be lost if we ignore the mystical dimension of his thought. Some of the most intractable forms of suffering may have spiritual dimensions that purely psychological frameworks cannot adequately address.

The Concrete Universal: Kierkegaard’s Method and Style

Understanding Kierkegaard requires attention not only to what he said but how he said it. Unlike philosophers who write systematic treatises under their own names, Kierkegaard employed a dizzying array of pseudonyms, each representing a different perspective on existence. Johannes de Silentio, Constantine Constantius, Johannes Climacus, Anti-Climacus—these pseudonymous authors allowed Kierkegaard to explore various positions without claiming final authority, enacting in his very method the recognition that truth is subjective and must be appropriated by each individual through their own passionate engagement.

This literary strategy reflects Kierkegaard’s conviction that indirect communication is necessary for communicating existential truth. One cannot simply transfer knowledge about how to exist authentically the way one might convey empirical information. Instead, the reader must be provoked, challenged, and invited to undertake their own process of self-examination. Kierkegaard’s use of irony, paradox, and deliberately provocative statements serves this maieutic purpose, functioning like the Socratic method to midwife the birth of authentic selfhood in the reader.

This aspect of Kierkegaard’s work has implications for therapeutic practice. Existential therapists recognize that healing cannot be imposed from outside but must arise from the client’s own engagement with their existence. The therapist’s role becomes not that of expert who fixes the client but of companion who facilitates the client’s own process of self-discovery. This collaborative, exploratory stance owes much to Kierkegaard’s recognition that existential truth cannot be directly taught but only awakened.

The Dialectic of Freedom and Anxiety

Returning to Kierkegaard’s analysis of anxiety, we find therapeutic wisdom that becomes more relevant as our culture accelerates into ever-expanding possibilities. In an age of nearly infinite choices—career paths, relationship options, lifestyle possibilities, identity configurations—many people experience precisely the vertigo of freedom that Kierkegaard described. The abundance of options, rather than liberating us, can become paralyzing. We suffer from what contemporary psychologists call “choice overload” or “analysis paralysis,” modern versions of the despair of possibility that Kierkegaard identified.

Kierkegaard understood that freedom is not the absence of constraints but the capacity to commit to particular choices despite uncertainty. The anxious individual who keeps all options open, who refuses to choose definitively, actually loses their freedom in the very attempt to preserve it. They become enslaved to possibility itself, unable to actualize any particular way of being because they cannot relinquish alternative possibilities.

Therapy informed by these insights helps clients develop what we might call existential tolerance—the capacity to bear the anxiety of commitment, to choose a path forward while acknowledging that other paths must be forsaken, to accept the limitations inherent in being a finite creature with finite time. This differs from merely managing anxiety symptoms through techniques like cognitive restructuring or relaxation training. Instead, it involves a fundamental shift in how clients understand and relate to the anxiety that accompanies meaningful choice.

The Question of Authenticity

The concept of authenticity, so central to existential thought and practice, finds one of its earliest and most profound articulations in Kierkegaard’s work. To be authentic, in the Kierkegaardian sense, is not to express some pre-existing inner self but to take responsibility for who we are becoming through our choices. Authenticity involves recognizing ourselves as authors of our existence rather than merely products of external forces.

This emphasis on authenticity has become, if anything, more urgent in our contemporary context. Social media, consumer culture, and the proliferation of prescribed identities all pressure individuals toward conformity and inauthenticity. We are tempted to understand ourselves primarily through external validation, to construct selves designed for public consumption, to live in what Kierkegaard called the aesthetic mode where we are constantly responsive to immediate stimuli and others’ judgments.

Kierkegaard’s critique of “the public” and “the crowd” in works like “The Present Age” prefigures contemporary concerns about social media’s effects on selfhood. He warned that losing oneself in collective opinion, in what “they” think or what “everyone” is doing, represents a fundamental abdication of individual responsibility. The authentic self emerges not through conformity but through the courageous assertion of individual existence in the face of social pressure toward uniformity.

For therapists, this means attending to how clients have internalized social expectations, cultural narratives, and familial pressures that may obstruct authentic self-expression. It means helping clients distinguish between the self they have been told they should be and the self they might become through genuine choice. This therapeutic work requires what Martin Buber called an “I-Thou” relationship, where the therapist encounters the client as a unique individual rather than as an instance of a diagnostic category or therapeutic technique.

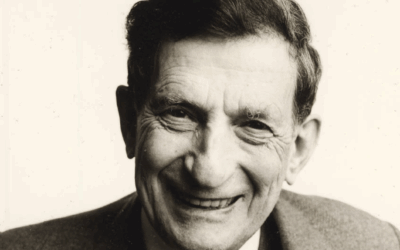

Kierkegaard’s Life: The Crucible of His Philosophy

To understand Kierkegaard’s philosophy fully requires attention to his biographical circumstances, for his thought emerged directly from his lived experience of anxiety, melancholy, and profound personal struggle. Born in Copenhagen in 1813, Søren Aabye Kierkegaard was the youngest of seven children in a prosperous but troubled household. His father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, was a wealthy merchant who had risen from poverty through his wool trade but who was haunted by a sense of guilt stemming from having cursed God as a young shepherd boy. This paternal melancholy cast a shadow over the household, and Søren inherited both his father’s intellectual gifts and his propensity toward depression.

The most formative event in Kierkegaard’s life was his relationship with Regine Olsen, whom he met in 1837 when she was fourteen. After a courtship of several years, they became engaged in 1840, but Kierkegaard broke off the engagement the following year, a decision that would torment him for the rest of his life. His reasons for the break remained somewhat obscure even to Regine, though scholars have speculated that Kierkegaard felt himself unsuited for marriage due to his melancholy temperament, his sense of divine calling, and perhaps some “thorn in the flesh” that he never fully revealed.

This broken engagement became the existential wound from which much of Kierkegaard’s greatest work flowed. Many of his pseudonymous works can be read as attempts to communicate with Regine, to explain the inexplicable, to justify a decision that could never be adequately justified. “Either/Or,” published shortly after the break, explores the aesthetic and ethical modes of existence partly through the lens of romantic love and marriage. “Repetition” and “Fear and Trembling,” both published on the same day in 1843, wrestle with whether what has been lost can be regained, whether the sacrifices demanded by faith can ever be reconciled with human happiness.

Kierkegaard lived his entire life in Copenhagen, rarely traveling far from the city where he was known and often mocked as an eccentric. He inherited his father’s wealth and was able to devote himself to writing without financial concerns, though he eventually exhausted his inheritance through his prodigious literary output. In his later years, he became embroiled in a bitter public conflict with “The Corsair,” a satirical newspaper that subjected him to relentless ridicule, portraying him as a hunchback dandy wandering Copenhagen’s streets in mismatched trousers.

This public mockery intensified Kierkegaard’s sense of isolation and his critique of mass society. He saw himself as a solitary individual swimming against the currents of his age, attempting to reintroduce Christianity into Christendom at a time when Christianity had become so culturally domesticated that it had lost its radical, transformative power. His final years were marked by an increasingly vitriolic attack on the Danish State Church, which he saw as betraying authentic Christianity through its comfortable accommodation with bourgeois society.

Kierkegaard collapsed on the street in Copenhagen in October 1855 and died in November of the same year at the age of forty-two, possibly from complications of a spinal disease. He had accomplished an astonishing literary output in his brief life, producing works that would influence philosophy, theology, literature, and eventually psychotherapy for generations to come. At his funeral, his nephew protested the church’s involvement in the service, claiming that Kierkegaard himself would have rejected it—a final irony for a man who spent his life wrestling with the relationship between individual faith and institutional religion.

Legacy and Ongoing Relevance

The influence of Kierkegaard on psychotherapy continues to evolve as new generations of therapists discover his insights. In an age characterized by increasing anxiety, meaninglessness, and identity confusion, his work speaks with particular urgency. The existential questions he raised—How shall I live? What does it mean to be authentic? How can I bear the anxiety of freedom?—are precisely the questions that bring many clients into therapy.

Moreover, Kierkegaard’s insights complement rather than contradict other therapeutic approaches. Therapists working from cognitive-behavioral, psychodynamic, or systems perspectives can enrich their practice by attending to the existential dimensions of their clients’ struggles. A depressive episode may involve distorted cognitions that can be challenged through CBT, but it may also reflect what Kierkegaard would recognize as a crisis of meaning, a despair rooted in how the person relates to themselves and their existence.

The integration of existential and mindfulness-based approaches represents another frontier where Kierkegaardian insights remain relevant. While mindfulness has roots in Buddhist philosophy, the emphasis on present-moment awareness and acceptance of difficult emotions aligns with Kierkegaard’s recognition that we must confront rather than flee from the anxiety and despair inherent in existence. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and similar approaches help clients develop the kind of presence and acceptance that Kierkegaard understood as necessary for authentic existence.

As psychotherapy continues to grapple with questions of meaning, values, and human flourishing in an increasingly secular age, Kierkegaard’s work provides resources that are simultaneously deeply rooted in Christian faith and remarkably translatable into secular therapeutic contexts. His insistence that each individual must find their own path, his refusal to offer easy answers, and his profound respect for human freedom and dignity make him an invaluable guide for therapists seeking to help clients navigate the complexities of contemporary existence.

Timeline of Søren Kierkegaard’s Life

1813 – Born May 5 in Copenhagen, Denmark, the youngest of seven children to Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard and Ane Sørensdatter Lund Kierkegaard.

1819 – Begins formal schooling at the School of Civic Virtue in Copenhagen.

1830 – Enrolls at the University of Copenhagen to study theology.

1834 – Mother dies March 31. Later the same year, his sister Nicoline Christiane dies.

1837 – Meets Regine Olsen for the first time at a party hosted by the Rørdam family.

1838 – Father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, dies August 9. This death profoundly affects Søren and resolves him to complete his theological studies. Experiences a religious awakening, noted in his journals as a “great earthquake.”

1840 – Completes his master’s thesis “On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates.” Becomes engaged to Regine Olsen on September 10.

1841 – Breaks off his engagement to Regine Olsen on October 11. Defends his dissertation on irony and receives his degree. Travels to Berlin where he attends lectures by Friedrich Schelling.

1843 – Publishes “Either/Or” under the pseudonym Victor Eremita on February 20. Publishes “Fear and Trembling” and “Repetition” on the same day, October 16, under the pseudonyms Johannes de Silentio and Constantine Constantius respectively. Also publishes “Three Upbuilding Discourses” under his own name.

1844 – Publishes “Philosophical Fragments” under the pseudonym Johannes Climacus and “The Concept of Anxiety” under Vigilius Haufniensis. Also publishes additional upbuilding discourses.

1845 – Publishes “Stages on Life’s Way” under multiple pseudonyms. Continues publishing upbuilding discourses under his own name.

1846 – Publishes “Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments” under the pseudonym Johannes Climacus, a massive work that he intends as the conclusion of his authorship. Becomes embroiled in conflict with “The Corsair,” a satirical newspaper that subjects him to public ridicule.

1847 – Publishes “Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits” and “Works of Love” under his own name, marking a shift toward more explicitly religious writing.

1848 – Publishes “Christian Discourses.” Experiences what he describes as a second conversion or spiritual awakening. Regine Olsen marries Johan Frederik Schlegel, an event that deeply affects Kierkegaard.

1849 – Publishes “The Sickness Unto Death” under the pseudonym Anti-Climacus and “The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air” under his own name. Also publishes several other shorter works.

1850 – Publishes “Training in Christianity” under the pseudonym Anti-Climacus, a work that intensifies his critique of established Christianity.

1851 – Publishes “For Self-Examination” and “Judge for Yourself!” under his own name, continuing his examination of authentic Christian existence.

1854 – Death of Bishop Jakob Peter Mynster in January, whom Kierkegaard had refrained from publicly attacking during his lifetime out of respect for his father’s admiration for the bishop. Begins publishing articles in “The Fatherland” newspaper attacking the Danish State Church.

1855 – Publishes his own periodical, “The Instant,” containing increasingly vitriolic attacks on established Christianity. Collapses on the street in Copenhagen on October 2. Refuses communion from a priest on his deathbed, insisting that only a layman can administer it to him. Dies November 11 at Frederiks Hospital at the age of forty-two.

1859 – Regine and Johan Frederik Schlegel depart for the Danish West Indies, where Johan serves as governor. Regine reportedly never recovered fully from her relationship with Kierkegaard.

Post-1855 – Kierkegaard’s works gradually gain recognition internationally, particularly in Germany and France. By the early twentieth century, his influence on existentialism becomes widely acknowledged.

0 Comments