Guy Debord: Exploring the Situationist Critique of Modern Society

I. Who was Guy Debord

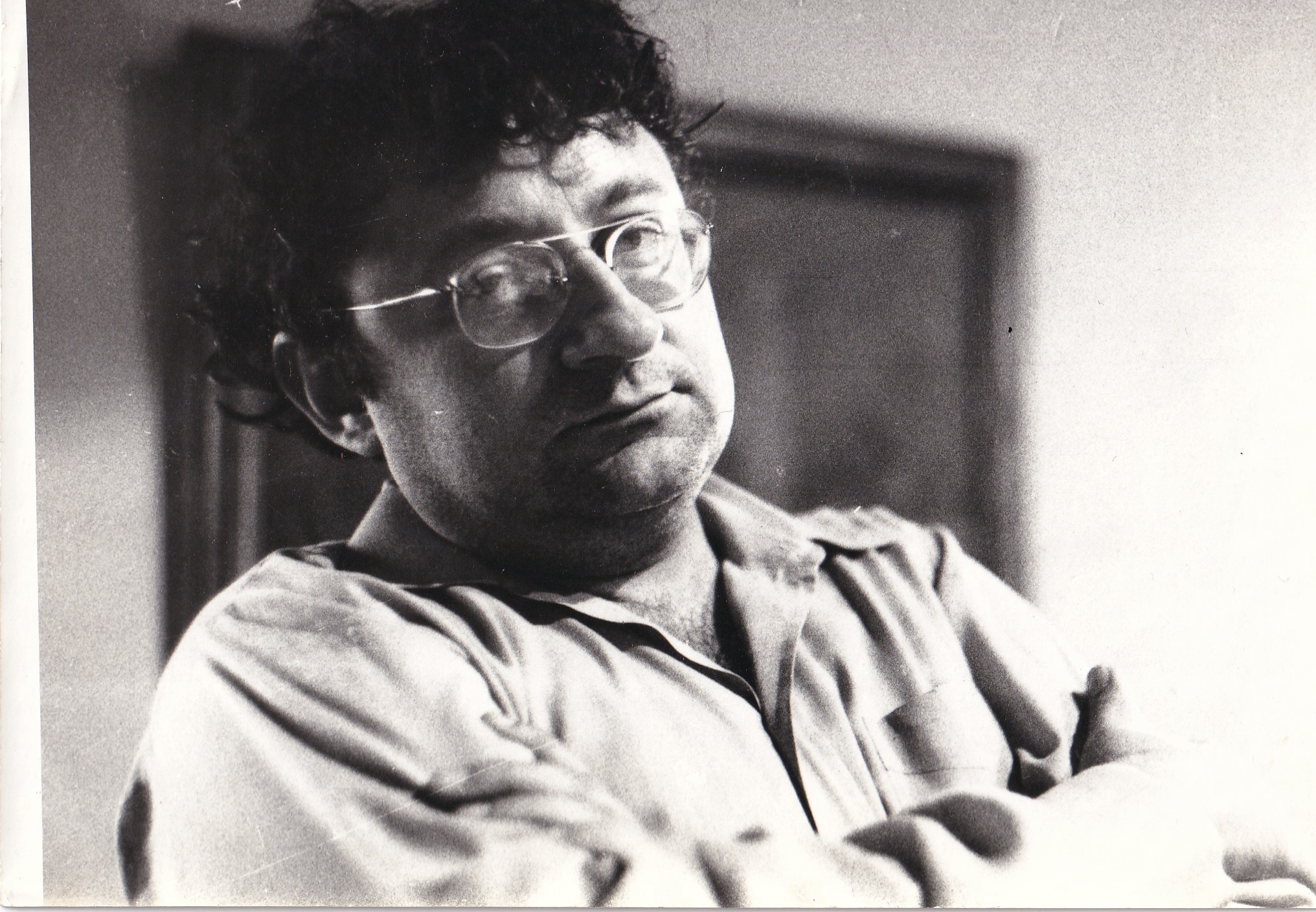

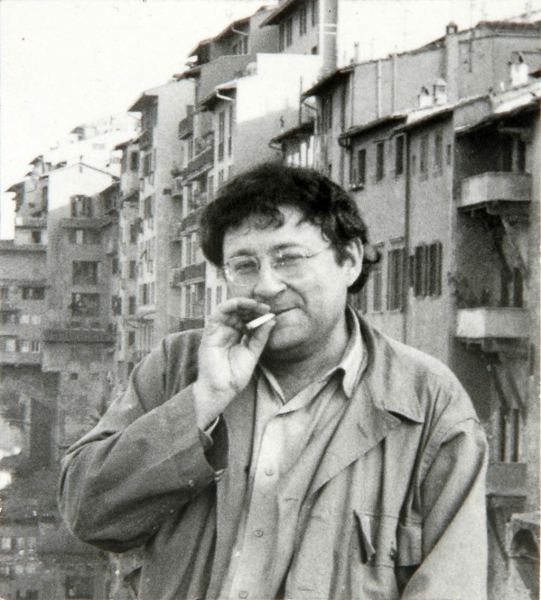

Guy Debord (1931-1994) was a French Marxist theorist, philosopher, filmmaker, and founding member of the Situationist International, a radical avant-garde movement that sought to transform everyday life through the fusion of art and politics. Debord’s groundbreaking book “The Society of the Spectacle” (1967) presented a scathing critique of modern capitalist society, arguing that authentic social life had been replaced with its superficial representation – the “spectacle.” Debord’s ideas, while rooted in Marxism, also drew from a wide range of fields including psychology, anthropology, and comparative religion, making his work relevant to psychologists, Jungian analysts, anthropologists, and religious studies scholars interested in the psychosocial impacts of modern society.

This paper explores the life and ideas of Guy Debord, situating his thought within the historical and intellectual context of the mid-20th century and tracing its enduring influence on contemporary debates in psychology, anthropology, and related fields. By examining Debord’s key concepts, such as the spectacle, alienation, and détournement, and by considering their implications for therapeutic practice and social analysis, this paper seeks to illuminate the ongoing relevance of Situationist theory for understanding and transforming the conditions of modern life.

II. Biography of Guy Debord

Guy Debord was born in Paris in 1931 to a family of wine merchants. He studied at the University of Paris, focusing on law and philosophy, but became disillusioned with academia and dropped out to pursue a more radical path. In the early 1950s, Debord became involved with the Letterist International, an avant-garde artistic and political movement that sought to revolutionize language and communication. Through his participation in the Letterist International, Debord developed many of the key concepts and strategies that would later inform the Situationist International, including the notion of détournement, the subversive appropriation and recontextualization of existing cultural materials.

In 1957, Debord co-founded the Situationist International with a group of radical artists and theorists, including Asger Jorn, Michèle Bernstein, and Raoul Vaneigem. As a central theorist and organizer of the group, Debord played a pivotal role in the development of Situationist theory and practice, which sought to unite avant-garde aesthetics with revolutionary politics. The Situationists were deeply involved in the student and worker uprisings of May 1968 in France, which brought the country to the brink of revolution and cemented Debord’s status as a major intellectual figure of the 20th century.

In the later years of his life, Debord continued to develop Situationist theory through his writings and films, such as “The Society of the Spectacle” (1973) and “In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni” (1978). He also wrote extensively about his own life and ideas in works such as “Panegyric” (1989) and “This Bad Reputation” (1993). Debord struggled with alcoholism and depression throughout his life, and died by suicide in 1994 at the age of 62.

III. Overview of Key Ideas

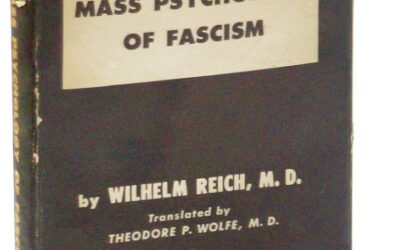

At the heart of Debord’s thought is the concept of the spectacle, which he defined as the system of images, commodities, and ideologies that mediates social relations in modern capitalist society. In his seminal work “The Society of the Spectacle” (1967), Debord argued that the spectacle had come to dominate all aspects of social life, replacing authentic experience with its superficial representation. “Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation,” he wrote, “The spectacle is not a collection of images; it is a social relation between people that is mediated by images.”

For Debord, the spectacle was not merely a distortion of reality, but a totalizing force that shaped individual consciousness, desire, and behavior. In a society dominated by the spectacle, individuals become passive spectators, consuming pre-packaged experiences and identities rather than actively creating their own. This leads to widespread alienation, as people become estranged from their own desires, creativity, and capacity for self-determination. “The spectacle’s function in society is the concrete manufacture of alienation,” Debord wrote, “The spectacle is the technical realization of the exile of human powers into a beyond; it is separation perfected within the interior of man.”

The spectacle also fragments social life into a series of isolated, commodified experiences, replacing genuine community with atomized individuals pursuing private interests. This fragmentation makes it difficult for individuals to develop a coherent sense of self or to engage in meaningful social change. “Spectators are linked solely by a one-way relationship to the very center that maintains their isolation from each other,” Debord wrote, “The spectacle thus reunites the separate, but it reunites it as separate.”

To resist the spectacle, the Situationists developed a range of strategies and tactics, including détournement, the subversive appropriation and recontextualization of existing cultural materials, and the construction of situations, moments of authentic, unmediated experience that could puncture the veil of the spectacle and reveal the possibility of a different way of life. “The construction of situations begins beyond the ruins of the modern spectacle,” Debord wrote, “It is easy to see how much the very principle of the spectacle – nonintervention – is linked to the alienation of the old world. Conversely, the most pertinent revolutionary experiments in culture have sought to break the spectators’ psychological identification with the hero so as to draw them into activity.”

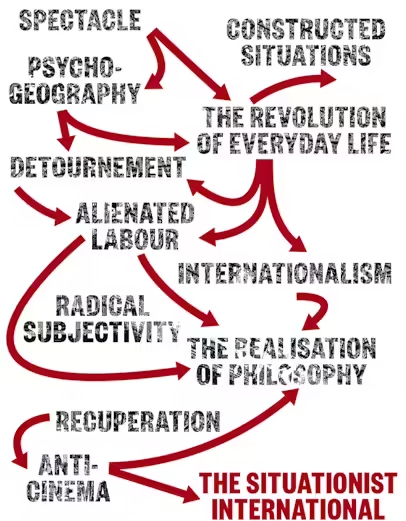

Glossary of Guy Deboard and Situationalists International Concepts:

Détournement –

Subversive misappropriation of media, images and ideas to undermine their original meaning

Dérive –

An unplanned journey through an urban landscape to study its psychogeography

Unitary urbanism –

Rethinking architecture and city planning to create spaces conducive to play and authentic living

Constructed situation –

Orchestrated events aimed at provoking critical awareness and desire for social revolution

Psychogeography –

The study of the specific effects of the geographical environment on the emotions and behavior of individuals. The Situationists used psychogeography to explore and challenge the organization of urban spaces under capitalism.

Détournement –

he reuse or hijacking of elements of media, art, or culture in ways that subvert their original meaning. The Situationists employed détournement as a revolutionary tactic to undermine capitalist spectacle.

Alienated labour –

The condition of workers under capitalism, divorced from their humanity and creative potential. The Situationists aimed to overcome alienated labor through the revolution of everyday life.

Radical subjectivity –

Emphasis on subjective lived experience and desire as a basis for revolutionary consciousness. The Situationists sought to awaken radical subjectivity suppressed by spectacular society.

Recuperation –

The neutralizing of subversive ideas/practices by absorbing them back into dominant society. The Situationists warned of recuperation as a constant threat to oppositional movements.

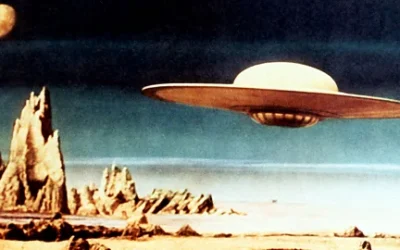

Anti-cinema –

Rejection of conventional film in favor of forms serving revolutionary ends. The Situationists experimented with anti-cinematic techniques to contest the passivity of spectatorship.

The realization of philosophy –

The Situationist goal of abolishing the gap between philosophical theory and lived practice. They saw the realization of philosophy as key to the revolution of everyday life.

IV. Implications for Psychotherapy

Debord’s critique of the spectacle has significant implications for psychotherapy, particularly in understanding the impact of trauma in modern society. The spectacle’s alienating and fragmenting effects can be seen as a form of collective trauma, disrupting individuals’ sense of self, agency, and connection to others.

As Debord wrote, “The spectacle is the nightmare of imprisoned modern society which ultimately expresses nothing more than its desire to sleep. The spectacle is the guardian of sleep.”

Moreover, the constant barrage of images and narratives produced by the spectacle can overwhelm individuals’ capacity to process and make meaning of traumatic experiences, leading to a sense of disconnection and inauthenticity. “The spectacle makes one see the world by means of various specialized mediations (it can no longer be grasped directly),”

Debord wrote, “It is a world vision which has become objectified.”

In this context, the therapeutic process can be understood as a means of helping individuals to deconstruct the influence of the spectacle on their self-understanding and to reconnect with their authentic desires and experiences. By fostering a sense of authorship and meaning-making in clients’ lives, and by emphasizing the value of experiential awareness, creative expression, and relational authenticity, therapists can help to build resilience against the spectacle’s alienating effects and to support the process of individual and collective empowerment.

This approach resonates with the work of humanistic and existential psychotherapists, who have long emphasized the importance of authenticity, agency, and self-actualization in the therapeutic process. It also connects with more recent developments in trauma-informed therapy, which recognize the ways in which trauma can disrupt individuals’ sense of self and agency, and which seek to support clients in developing new narratives and experiences of empowerment.

At the same time, a Situationist-informed approach to psychotherapy would also attend to the broader social and political context in which individual struggles take place. By helping clients to situate their experiences within the larger framework of the spectacle, therapists can support the development of a critical consciousness that recognizes the ways in which personal struggles are connected to systemic forms of oppression and alienation.

Ultimately, a psychotherapy informed by Debord’s ideas would seek not only to alleviate individual suffering, but also to contribute to the larger project of social transformation. By supporting clients in developing the skills and capacities necessary for authentic, unmediated experience and collective action, therapists can play a role in the creation of a world beyond the spectacle, in which human creativity, agency, and connection can flourish.

V. Relevance to Other Disciplines

Debord’s ideas have significant relevance to a range of other disciplines, including Jungian psychology, modern anthropology, and psychoanalysis. In each of these fields, Situationist theory offers a powerful framework for understanding the ways in which modern society shapes individual and collective experience, and for imagining alternative possibilities for social and psychological life.

A. Jungian Psychology

In Jungian psychology, there are striking parallels between Debord’s critique of the spectacle and Jung’s concern with the modern individual’s disconnection from the depths of the psyche. For Jung, the process of individuation, or psychological integration and self-realization, required a confrontation with the unconscious and a reconnection with the archetypal dimensions of human experience. In a society dominated by the spectacle, however, this process is increasingly difficult, as individuals are bombarded with superficial images and narratives that obscure the deeper layers of the psyche.

Debord’s emphasis on the importance of reclaiming agency and self-determination resonates with Jung’s vision of individuation as a process of inner liberation and self-discovery. Moreover, both thinkers emphasized the importance of collective meaning and shared symbolic experience in the development of authentic selfhood. For Jung, this took the form of the collective unconscious and the archetypes that structure human experience across cultures and historical periods. For Debord, it manifested in the Situationist vision of a society based on the free creation and exchange of meaningful situations and experiences.

These themes have been taken up by post-Jungian thinkers such as James Hillman, who has offered a trenchant critique of the psychological impact of consumer culture. Hillman argues that the spectacle reduces the complexity and depth of the psyche to a series of marketable images and personalities, leading to a flattening of human experience and a loss of connection to the soul. In response, he calls for a “re-visioning” of psychology that would attend to the poetic and imaginative dimensions of the psyche, and that would resist the colonization of the inner world by the forces of the spectacle.

Comparisons to Jungian Analysts

While Debord’s Marxist framework differs significantly from Jungian psychology, there are intriguing parallels between his ideas and those of certain Jungian analysts:

James Hillman

Like Debord, post-Jungian theorist James Hillman offered a critique of modern consumer culture’s impact on the psyche. Both thinkers emphasized the importance of imagination and creativity in resisting the flattening effects of commodification.

Wolfgang Giegerich

Giegerich’s concept of the “soul’s logical life” and his critique of literalized thinking bear some resemblance to Debord’s analysis of how the spectacle reifies social relations.

Erich Neumann

Neumann’s work on the psychological stages of cultural development can be seen as complementary to Debord’s historical analysis of the evolution of the spectacle.

Marie-Louise von Franz

Von Franz’s studies of projection and the shadow have some resonance with Debord’s ideas about how the spectacle shapes desire and identity.

B. Modern Anthropology

In modern anthropology, Debord’s ideas have been influential in the study of media and visual culture, as well as in the analysis of everyday life and urban space. The spectacle can be understood as a cultural system that shapes both individual and collective experience, making it a key object of anthropological inquiry.

Anthropologists such as Marc Augé have drawn on Situationist concepts in their analyses of the “non-places” of supermodernity, the anonymous, interchangeable spaces of airports, shopping malls, and highways that characterize the contemporary landscape. For Augé, these spaces are defined by their lack of historical and cultural specificity, and by the solitary contractuality of the individuals who pass through them. In this sense, they can be seen as emblematic of the spectacle’s erosion of authentic social bonds and meaningful places.

Other anthropologists have explored the ways in which the spectacle shapes the construction of cultural identities and the circulation of cultural meanings. In his study of the Kayapo people of the Brazilian Amazon, for example, Terence Turner has shown how the introduction of video technology and mass media has transformed Kayapo culture and politics, leading to the emergence of new forms of self-representation and cultural activism. Turner argues that the Kayapo have used the tools of the spectacle to create a “counter-spectacle” that challenges dominant representations of indigenous peoples and asserts the value of traditional ways of life.

C. Psychology and Psychoanalysis

In the field of psychology and psychoanalysis, Debord’s critique of the spectacle resonates with the work of thinkers such as Erich Fromm, who analyzed the psychological impact of the “marketing character” in modern consumer society. For Fromm, the market economy creates a personality type that is characterized by a lack of authentic individuality, a dependence on external validation, and a constant need to adapt to the changing demands of the market. This leads to a sense of alienation and insecurity, as individuals are unable to develop a stable sense of self or to find meaning and purpose in their lives.

Fromm’s analysis echoes Debord’s critique of the spectacle’s reduction of human beings to passive consumers of prefabricated experiences and identities. Both thinkers emphasize the need for individuals to reclaim their agency and creativity in the face of the market’s colonization of everyday life. For Fromm, this takes the form of the “productive orientation,” a way of being in the world that is characterized by a sense of inner directedness, a capacity for love and reason, and a commitment to the realization of human potential.

Psychoanalytic thinkers have also drawn on Situationist ideas in their critiques of the psychological normalization of oppression and domination. In his work on the psychopathology of colonialism, for example, Frantz Fanon used the concept of the spectacle to analyze the ways in which colonial power operates through the creation of a world of appearances that masks the reality of violence and exploitation. For Fanon, the colonized subject is forced to internalize the colonizer’s image of them as inferior and subhuman, leading to a profound sense of alienation and self-doubt.

Fanon’s analysis suggests that the spectacle is not only a feature of advanced capitalist societies, but also a key mechanism of colonial and neo-colonial domination. In this sense, the Situationist critique of the spectacle can be seen as part of a larger project of decolonization and liberation, one that seeks to challenge the psychological and cultural foundations of oppression and to create new forms of subjectivity and social relations.

VI. Philosophical Influences on the Situationist International:

The Situationist International drew upon a wide range of philosophical and theoretical influences, integrating them into their unique critique of modern capitalist society. Some key influences include:

Psychoanalysis and Jacques Lacan: The Situationists were influenced by psychoanalytic theories, particularly the work of Jacques Lacan. They explored the role of desire and the unconscious in shaping social relations and the potential for liberating desire from the repressive structures of capitalism.

The Frankfurt School:

The critical theory of the Frankfurt School, especially the work of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, informed the Situationist critique of mass culture and the commodification of everyday life. The Situationists shared the Frankfurt School’s concern with the ways in which capitalism infiltrates and manipulates subjectivity.

Marxism:

The Situationists were deeply influenced by Marxist thought, particularly the concepts of alienation, commodification, and the revolutionary potential of the proletariat. They sought to update and extend Marxist analysis to account for the new conditions of postwar consumer society.

Henri Lefebvre:

French Marxist philosopher Henri Lefebvre was a significant influence on the Situationists, especially his concepts of the critique of everyday life and the social production of space. Lefebvre’s work helped to shape the Situationist understanding of the political and revolutionary significance of daily lived experience.

Media theory:

The Situationists were attentive to the growing power and influence of media in modern society. They drew upon emerging media theories to analyze the role of spectacle and representation in maintaining capitalist social relations. This concern with media and spectacle prefigured later developments in digital and global media theory.

Dada and Surrealism:

The Situationists were inspired by the avant-garde movements of Dada and Surrealism, which sought to rupture the boundaries between art and everyday life. The Situationists adapted avant-garde techniques like collage and automatic writing for their own subversive purposes.

Legacy and Implications

The life and ideas of Guy Debord remain as relevant today as they were in the 1960s, as we continue to grapple with the challenges of living in a society dominated by the spectacle. Debord’s uncompromising critique of the alienation, fragmentation, and passivity induced by the spectacle continues to inspire new generations of thinkers and activists, who seek to resist the colonization of everyday life by the forces of capitalism and to create spaces of authentic, unmediated experience.

By engaging critically with Debord’s thought and exploring its implications for psychology, anthropology, religious studies, and other fields, we can deepen our understanding of the complex interplay between individual experience and social structure, and work towards the creation of a world beyond the spectacle. This requires an integrative approach that draws on the insights of multiple disciplines, recognizing the ways in which the psychological, the cultural, and the political are inextricably intertwined.

For psychologists and psychotherapists, Debord’s ideas offer a powerful framework for understanding the impact of trauma and alienation in modern society, and for developing therapeutic approaches that support individuals in reclaiming their agency and creativity. By attending to the broader social and political context in which individual struggles take place, therapists can contribute to the larger project of social transformation and help to create a world in which human potential can be fully realized.

At the same time, Debord’s critique of the spectacle challenges us to confront the ways in which we are all implicated in the reproduction of alienated social relations, and to take responsibility for our own participation in the spectacle. This requires a willingness to question the taken-for-granted assumptions of our culture, to experiment with new forms of social and psychological life, and to create spaces of resistance and alternative possibility.

Ultimately, the enduring significance of Guy Debord’s work lies in its challenge to the complacency and conformism of modern society, and in its insistence on the possibility of a different way of life. In an era of deepening social fragmentation and ecological crisis, Debord’s call to reclaim human agency, creativity, and connectedness takes on renewed urgency. As we struggle to imagine and create a world beyond the spectacle, we can draw inspiration from Debord’s unwavering commitment to the revolutionary transformation of everyday life.

VII. Timeline of Guy Debord’s Life

1931:

Born in Paris, France.

1951:

Joins the Letterist International, a radical art and political group.

1952:

Begins experimenting with psychogeography and the theory of the dérive.

1957:

Founds the Situationist International (SI) with other avant-garde artists and activists.

1958:

Publishes “Theses on Cultural Revolution,” outlining the SI’s program.

1961:

Expelled from the SI for allegedly prioritizing theoretical over practical activity.

1967:

Publishes “The Society of the Spectacle,” his most influential work.

1968:

Participates in the May 1968 uprisings in France, which are heavily influenced by Situationist ideas.

1971:

Publishes “The Veritable Split in the International,” reflecting on the SI’s dissolution.

1972:

The SI officially dissolves.

1973:

Releases the film version of “The Society of the Spectacle.”

1978:

Publishes “In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni,” a cinematic memoir.

1988:

Publishes “Comments on the Society of the Spectacle,” updating his analysis for the late 20th century.

1989:

Publishes “Panegyric,” the first volume of his autobiographical writings.

1991:

Publishes “Panegyric, Volume 2.”

1994:

Dies by suicide in Bellevue-la-Montagne, Auvergne, France.

VIII. Major Works and Publications

“Mémoires” (1959) – A collaboratively produced “anti-book” featuring poetry, collage, and detourned comic strips, co-authored with the Danish artist Asger Jorn.

“The Society of the Spectacle” (1967) – Debord’s most famous work, a theoretical critique of modern capitalist society and the alienating effects of the spectacle.

“On the Poverty of Student Life” (1966) – A Situationist pamphlet that criticized the capitalist university system and called for the revolutionary self-organization of students.

“The Decline and Fall of the Spectacle-Commodity Economy” (1966) – An analysis of the Watts riots in Los Angeles, which Debord saw as a rebellion against the spectacle-commodity economy.

“The Situationists and the New Forms of Action in Politics and Art” (1963) – An essay outlining the Situationist strategy of creating new forms of revolutionary action and organization.

“In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni” (1978) – A film and accompanying book that reflects on Debord’s life and the history of the Situationist International.

“Comments on the Society of the Spectacle” (1988) – An update to Debord’s 1967 book, analyzing the development of the spectacle in the late 20th century.

“Panegyric” (1989) and “Panegyric, Volume 2” (1997) – A two-volume autobiographical work in which Debord reflects on his life, ideas, and the history of the Situationist International.

IX. Historical and Intellectual Context

To fully understand the significance of Guy Debord’s ideas, it is necessary to situate them within the broader historical and intellectual context of the mid-20th century. Debord’s thought emerged in the aftermath of World War II, as Europe was grappling with the legacy of fascism and the rise of new forms of consumer capitalism. In France, the postwar period was marked by rapid economic growth, urbanization, and the expansion of the mass media, which transformed everyday life and gave rise to new forms of social and cultural experience.

At the same time, the postwar period saw the emergence of new forms of radical political thought and action, as young people and intellectuals sought to challenge the dominant values and institutions of capitalist society. In the 1950s and 1960s, a new generation of avant-garde artists and activists, inspired by Marxism, anarchism, and other radical philosophies, began to experiment with new forms of cultural and political intervention, from the Letterist International’s poetic provocations to the Situationist International’s critique of the spectacle.

Debord’s ideas were deeply influenced by the work of Karl Marx, particularly his critique of alienation and commodity fetishism. For Marx, the capitalist mode of production alienated workers from the products of their labor, from each other, and from their own creative potential, reducing them to mere appendages of the machine. Debord extended this analysis to the realm of everyday life, arguing that the spectacle alienated individuals from their own experiences and desires, transforming them into passive consumers of prefabricated images and commodities.

At the same time, Debord was also influenced by the avant-garde artistic movements of the early 20th century, particularly Dada and Surrealism. These movements sought to challenge the boundaries between art and life, and to create new forms of poetic and revolutionary experience. The Situationists drew on these traditions in their own practice, using techniques like détournement and the dérive to subvert the spectacle and create new situations of authentic, unmediated experience.

The Situationist International was also deeply involved in the political upheavals of the 1960s, particularly the May 1968 uprisings in France. The events of May ’68, which brought together students, workers, and intellectuals in a mass revolt against the authoritarian Gaullist regime, were heavily influenced by Situationist ideas and tactics. The SI’s critique of the university system, their call for the revolutionary self-organization of everyday life, and their emphasis on the creative and playful dimensions of political action all resonated with the spirit of the times.

In the aftermath of May ’68, however, the Situationist International began to fracture and dissolve, as internal conflicts and external pressures took their toll. Debord himself was expelled from the group in 1972, and spent the remainder of his life reflecting on the legacy of the SI and the continuing relevance of its ideas in a rapidly changing world.

Despite the dissolution of the SI, however, Debord’s ideas have continued to inspire new generations of radical thinkers and activists, from the punk and post-punk subcultures of the 1970s and 1980s to the anti-globalization and Occupy movements of the early 21st century. Debord’s critique of the spectacle, his emphasis on the revolutionary potential of everyday life, and his vision of a world beyond alienation and commodity fetishism continue to resonate with those seeking to challenge the dominant values and institutions of contemporary capitalism.

At the same time, Debord’s ideas have also been taken up by scholars and intellectuals across a range of disciplines, from philosophy and cultural studies to psychology and anthropology. The Situationist International’s emphasis on the constructed nature of social reality, their critique of the colonization of everyday life by the forces of the market, and their vision of a world beyond the spectacle have all been influential in shaping contemporary debates about the nature of subjectivity, power, and resistance in the modern world.

In engaging with Debord’s ideas today, it is important to recognize both their historical specificity and their enduring relevance. While the particular forms of the spectacle and the possibilities for resistance may have changed since Debord’s time, his fundamental insights into the alienating and fragmenting effects of modern capitalism continue to resonate with the experiences of individuals and communities around the world. By drawing on Debord’s ideas to develop new forms of critique and resistance, we can continue the Situationist project of transforming everyday life and creating a world beyond the spectacle.

Digital, Media, and Cultural Theorists and Philosophers

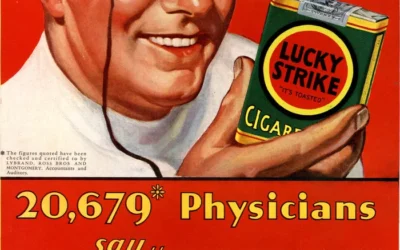

Bernays and The Psychology of Advertising

John B Calhoun and Universe 25

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

X. Bibliography

A. Primary Sources

Debord, Guy. “The Society of the Spectacle”. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. New York: Zone Books, 1994.

Debord, Guy. “Comments on the Society of the Spectacle”. Translated by Malcolm Imrie. London: Verso, 1998.

Debord, Guy. “Panegyric Volumes 1 & 2”. Translated by James Brook and John McHale. London: Verso, 2004.

Debord, Guy, and Asger Jorn. “Mémoires”. Paris: Situation, 1959.

Debord, Guy. “In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni”. Translated by Lucy Forsyth. London: Pelagian Press, 1991.

Knabb, Ken (ed). “Situationist International Anthology”. Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006.

Situationist International. “On the Poverty of Student Life”. 1966.

B. Secondary Sources

Jappe, Anselm. “Guy Debord”. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

McDonough, Tom. “Guy Debord and the Situationist International: Texts and Documents”. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004.

Merrifield, Andy. “Guy Debord”. London: Reaktion Books, 2005.

Plant, Sadie. “The Most Radical Gesture: The Situationist

International in a Postmodern Age”. London: Routledge, 1992.

Vaneigem, Raoul. “The Revolution of Everyday Life”. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. London: Rebel Press, 1994.

Wark, McKenzie. “The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and Glorious Times of the Situationist International”. London: Verso, 2011.

Wark, McKenzie. “The Spectacle of Disintegration: Situationist Passages out of the Twentieth Century”. London: Verso, 2013.

Apostolidès, Jean-Marie. “Debord: le naufrageur”. Paris: Flammarion, 2015. Co

Digital, Media, and Cultural Theorists and Philosophers

Bernays and The Psychology of Advertising

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

0 Comments