The concept of the daimon—an inner guiding force representing both our authentic self and the source of creative and healing potential—has appeared throughout the history of psychotherapy under various names and conceptualizations. From Socrates’ divine sign to contemporary neuroscientific understandings of intuition and trauma, major figures in psychology and psychotherapy have understood this vulnerable center of selfhood that lies paradoxically close to both our greatest gifts and deepest wounds. Through examining the work of Socrates, Jung, Hillman, Miller, and others, we explore how the daimon serves as both a source of authentic self-discovery and a gateway to understanding the wounded healer archetype. Recent neuroscience research revealing the neurobiological overlap between intuition and trauma responses offers new insights into why accessing the daimonic requires careful discernment in therapeutic practice.

The concept of the daimon—an inner guiding force representing both our authentic self and the source of creative and healing potential—has appeared throughout the history of psychotherapy under various names and conceptualizations. From Socrates’ divine sign to contemporary neuroscientific understandings of intuition and trauma, major figures in psychology and psychotherapy have understood this vulnerable center of selfhood that lies paradoxically close to both our greatest gifts and deepest wounds. Through examining the work of Socrates, Jung, Hillman, Miller, and others, we explore how the daimon serves as both a source of authentic self-discovery and a gateway to understanding the wounded healer archetype. Recent neuroscience research revealing the neurobiological overlap between intuition and trauma responses offers new insights into why accessing the daimonic requires careful discernment in therapeutic practice.

The Daimon as the Authentic Center

Throughout human history, individuals have reported experiencing an inner voice, presence, or force that seems to guide them toward their authentic path while simultaneously connecting them to their deepest vulnerabilities. This phenomenon, classically termed the “daimon” in Greek philosophy, represents a paradoxical aspect of human psychology: it is both our most authentic self and something that feels other; it is the source of our greatest creativity and healing potential while dwelling perilously close to our most profound traumas and wounds.

In the field of psychotherapy, this concept has emerged repeatedly, though often under different names: the Self, the inner voice, the authentic self, the soul, the creative unconscious, or simply intuition. What unites these various conceptualizations is the recognition that within each person exists a center of authenticity that, when accessed and honored, becomes a powerful force for healing and self-discovery. Yet this same center is often found wrapped around our earliest wounds, making the journey toward it both necessary and treacherous.

This paper examines how ten major figures in the history of psychology and psychotherapy have understood and worked with this daimonic dimension of human experience. We will explore how each thinker conceptualized this authentic center, how they understood its relationship to trauma and wounding, and what their work reveals about the nature of psychological healing. Finally, we will examine how contemporary neuroscience is beginning to map the biological substrates of these experiences, revealing why intuition and trauma responses share neural pathways and how modern somatic and parts-based therapies are learning to differentiate between them.

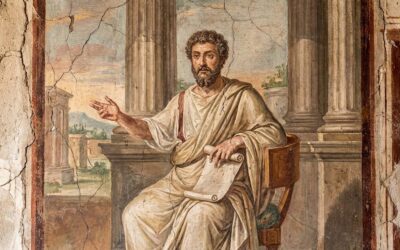

1. Socrates: The Original Daimonion

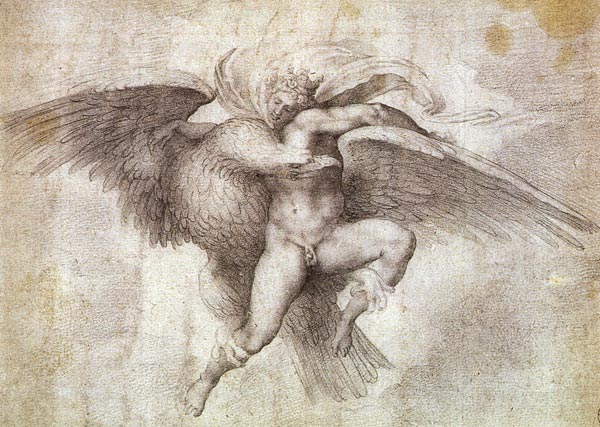

Socrates (470-399 BCE) provides our earliest and perhaps most influential account of the daimonic experience. He spoke frequently of his “daimonion”—a divine sign or inner voice that would warn him when he was about to make an error but never told him what to do positively. This distinction is crucial: Socrates’ daimon operated primarily through negation, creating space for authentic choice rather than dictating action.

What makes Socrates’ account particularly relevant to psychotherapy is his insistence that this inner voice was both deeply personal and somehow transpersonal. It belonged to him uniquely, yet it connected him to something greater than his individual ego. This paradox—that our most authentic self is simultaneously most intimately ours and yet beyond us—would echo through centuries of psychological thought.

Socrates also demonstrated the vulnerability inherent in following the daimonic path. His commitment to his inner voice ultimately led to his execution, illustrating how authenticity often requires confronting societal norms and expectations. For Socrates, the daimon was not a comfortable guide to happiness but a demanding presence that insisted on truth regardless of consequences.

2. Carl Jung: The Suppressed Voice and the Self

Carl Jung’s (1875-1961) relationship with his own daimonic experiences provides one of the most dramatic examples of how these phenomena intersect with both creativity and psychological crisis. Following his break with Freud, Jung underwent what he called his “confrontation with the unconscious,” a period of intense inner experiences that included visions, voices, and active imagination dialogues with inner figures.

Most notably, Jung’s original manuscript of “Memories, Dreams, Reflections” contained extensive discussions of his experiences with an inner voice that guided much of his theoretical development. These passages were largely removed by editors who feared they would damage Jung’s scientific credibility. This editorial suppression itself speaks to the cultural discomfort with daimonic experiences, even within psychology.

Jung conceptualized the daimon through his notion of the Self—the archetype of wholeness and the regulating center of the psyche. Unlike the ego, which represents our conscious identity, the Self encompasses both conscious and unconscious elements and serves as an inner guide toward individuation. Jung recognized that approaching the Self often meant encountering what he called the shadow—those rejected and wounded parts of ourselves that we have split off from consciousness.

The relationship between the Self and trauma in Jung’s work is complex. He understood that the path to wholeness necessarily involves integrating painful and rejected experiences. The daimon, in Jung’s view, often speaks through symptoms, dreams, and synchronicities, using the language of the unconscious to guide us toward what needs healing.

3. James Hillman: The Acorn and the Daimon

James Hillman (1926-2011) perhaps more than any other psychologist, placed the daimon at the center of his theoretical framework. In “The Soul’s Code,” Hillman developed his “acorn theory,” proposing that each person comes into the world with a unique daimon or calling that shapes their character and destiny.

Hillman’s daimon is not merely an inner guide but an active force that arranges our lives, including our pathologies and troubles, in service of our calling. He argued that many psychological symptoms are actually the daimon’s attempt to redirect us toward our authentic path. This perspective radically reframes psychological suffering: rather than simply pathology to be eliminated, our symptoms become potential communications from our deepest self.

Crucially, Hillman recognized that the daimon is amoral and demanding. It cares nothing for our comfort or conventional success, only for the fulfillment of our unique calling. This understanding helps explain why the daimonic path often leads through difficulty and why those who most fully embody their authentic selves often report both profound fulfillment and significant struggle.

4. Alice Miller: The Drama of the Gifted Child and the True Self

Alice Miller (1923-2010) approached the concept of the authentic self through her groundbreaking work on childhood trauma and narcissistic wounding. In “The Drama of the Gifted Child,” Miller described how sensitive children often develop a “false self” to meet their parents’ narcissistic needs, burying their “ttrue self”—their authentic feelings, needs, and expressions—deep within.

Miller’s “true self” bears striking resemblance to the classical daimon: it is our authentic center, the source of genuine vitality and creativity, yet it is often surrounded by layers of trauma and defense. She observed that many therapists are drawn to the profession precisely because they were such “gifted children”—highly sensitive individuals who learned early to attune to others’ needs at the expense of their own authenticity.

This connects directly to the concept of the wounded healer. Miller argued that therapists’ effectiveness often stems from their intimate knowledge of wounding and the journey back to authenticity. However, she warned that therapists who have not done their own deep work risk perpetuating cycles of narcissistic wounding with their clients.

Miller’s work illuminates why accessing the daimonic self is so challenging: it requires confronting not just our wounds but the defensive structures we’ve built around them. The false self, while limiting, has served a protective function, and dismantling it can feel threatening to our very existence.

5. D.W. Winnicott: The True Self and Creative Living

D.W. Winnicott (1896-1971) developed a sophisticated understanding of authentic selfhood through his concepts of the “true self” and “false self.” Like Miller, Winnicott saw the true self as arising from the infant’s spontaneous gestures and creative impulses. When these are received and mirrored by a “good enough” mother, the child develops a robust sense of authentic selfhood.

Winnicott’s daimon manifests as the capacity for creative living—the ability to feel real and to experience life as worth living. He understood that this creative capacity could be damaged by early environmental failures but never entirely destroyed. The true self, like the classical daimon, remains present even when hidden, waiting for conditions safe enough for its emergence.

What makes Winnicott’s contribution unique is his emphasis on the relational nature of authentic selfhood. The daimon, in his view, requires relationship for its full expression. This insight has profound implications for psychotherapy: the therapeutic relationship itself becomes the crucible within which the authentic self can emerge.

6. Marion Woodman: The Embodied Daimon

Marion Woodman (1928-2018) brought a uniquely somatic understanding to the concept of the daimon. Working at the intersection of Jungian psychology and body-centered therapy, Woodman recognized that the authentic self is not merely a psychological concept but a lived, embodied reality.

Woodman observed that trauma often causes a split between psyche and soma, leaving many people disconnected from their bodily wisdom. She saw the daimon as speaking through the body’s symptoms, dreams, and creative expressions. For Woodman, healing meant not just psychological insight but a literal re-embodiment of the soul.

Her work with eating disorders and addiction revealed how these conditions often represent misguided attempts to connect with the daimonic. The compulsive behaviors serve as distorted expressions of the soul’s legitimate hunger for meaning, beauty, and transcendence. This understanding transforms our approach to such conditions: rather than simply eliminating symptoms, we must help individuals find authentic ways to meet their daimonic needs.

7. R.D. Laing: The Divided Self and Authentic Experience

R.D. Laing (1927-1989) approached the daimon through his radical reimagining of madness and sanity. In “The Divided Self,” Laing argued that what we call schizophrenia often represents a desperate attempt to preserve some kernel of authentic selfhood in the face of an invalidating environment.

Laing’s daimon appears as the “inner self” that retreats from an unbearable false self system. While this retreat may manifest as psychosis, Laing saw it as potentially meaningful—a journey toward authentic being, however distorted. He famously declared that “madness need not be all breakdown. It may also be breakthrough.”

This perspective radically reframes severe mental illness. Rather than simply brain disease, psychosis becomes a potential daimonic crisis—a desperate attempt by the authentic self to break free from false adaptations. While Laing’s romanticization of madness has been rightly criticized, his recognition that even the most extreme states may contain daimonic meaning remains influential.

8. Wilhelm Reich: The Somatic Armor and Life Force

Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957) understood the daimon through the lens of bioenergy and what he called “orgone energy.” While his later work became increasingly eccentric, Reich’s early insights about character armor and the life force remain profoundly relevant to understanding the embodied nature of authenticity.

Reich observed that trauma and repression create chronic muscular tensions—”character armor“—that block the natural flow of life energy. This armor serves a defensive function but ultimately imprisons the authentic self. Reich’s daimon is thus the free-flowing life force that seeks expression through the body.

His work prefigures contemporary somatic therapies’ understanding of how trauma is held in the body and how accessing authenticity requires not just psychological work but literal, physical release. The daimonic, for Reich, is fundamentally an energetic phenomenon that can be blocked or freed through bodywork.

9. Fritz Perls: Contact and the Authentic Moment

Fritz Perls (1893-1970), founder of Gestalt therapy, approached the daimon through his emphasis on present-moment awareness and authentic contact. For Perls, the authentic self emerges not through analysis of the past but through full engagement with the here and now.

Perls’ daimon manifests as organismic self-regulation—the body-mind’s inherent wisdom about what it needs for health and growth. He believed that neurosis results from interrupting this natural regulatory process through various “contact boundary disturbances.”

The Gestalt approach recognizes that authenticity is not a fixed state but an ongoing process of contact and withdrawal, expression and integration. The daimonic appears in moments of full contact—when we drop our masks and meet life directly. This understanding emphasizes the dynamic, processual nature of authentic selfhood.

10. Peter Levine: Trauma, Instinct, and the Felt Sense

Peter Levine (1942-), developer of Somatic Experiencing, offers a contemporary understanding of how trauma and authenticity intertwine at the neurobiological level. Levine’s work reveals how unresolved trauma creates dysregulation in the nervous system that can muffle our connection to instinctual wisdom.

Levine’s daimon appears as the “felt sense”—a form of embodied knowing that transcends cognitive understanding. This felt sense can guide us toward healing, but trauma can make it difficult to distinguish between genuine intuition and trauma-based activation. His work provides practical tools for differentiating between these states.

This contribution is particularly valuable as it grounds the ancient concept of the daimon in contemporary neuroscience while maintaining respect for its phenomenological reality. Levine shows how accessing authentic guidance requires first establishing nervous system regulation.

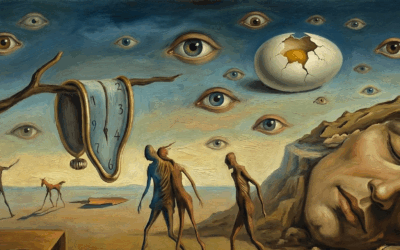

The Neuroscience of Intuition and Trauma: Shared Pathways

Recent neuroscientific research has revealed fascinating connections between intuitive knowing and trauma responses, helping explain why the daimon dwells so close to our wounds. Both intuition and trauma responses involve subcortical brain structures, particularly the amygdala, hippocampus, and brain stem, as well as the insula and anterior cingulate cortex.

Studies using fMRI technology show that intuitive insights often arise from the integration of subtle bodily signals processed by the insula—the same brain region hyperactivated in trauma responses. The vagus nerve, crucial for both social engagement and trauma responses, plays a key role in what we experience as “gut feelings” or intuitive knowing.

This neurobiological overlap explains why accessing authentic inner guidance can trigger trauma responses and why trauma survivors often struggle to trust their intuition. The same neural pathways that once detected danger now carry information about subtle environmental cues, creative insights, and authentic needs.

The right hemisphere of the brain, dominant for processing emotional, somatic, and holistic information, plays a crucial role in both traumatic memory encoding and intuitive perception. This explains why talk therapy alone often fails to resolve trauma or access deeper authenticity—these experiences are encoded in non-verbal, right-brain formats.

Differentiating Intuition from Trauma: Clinical Implications

Understanding the neurobiological overlap between intuition and trauma has profound implications for therapy. Somatic and experiential therapies are developing sophisticated methods for helping clients differentiate between authentic inner guidance and trauma-based activation:

- Nervous System Regulation: Intuition typically arises from a regulated nervous system state, while trauma responses involve dysregulation. Teaching clients to recognize their window of tolerance helps them identify when they’re accessing genuine wisdom versus trauma.

- Quality of Sensation: Intuitive knowing often has a quality of expansion, clarity, or settling, while trauma responses typically involve contraction, confusion, or activation. Learning to discern these subtle differences is crucial.

- Temporal Orientation: Trauma pulls us into past or future, while authentic guidance tends to be grounded in present-moment awareness.

- Relational Resonance: In the therapeutic relationship, therapists can serve as a tuning fork, helping clients recognize when they’re in touch with authentic truth versus trauma-based patterns.

- Somatic Markers: Different body sensations accompany intuition versus trauma activation. Developing somatic literacy helps clients navigate this terrain.

The Wounded Healer and the Therapist’s Daimon

The concept of the wounded healer, traced back to the Greek myth of Chiron, recognizes that many drawn to healing professions have intimate knowledge of wounding. This is not merely coincidence but reflects a daimonic calling—the transformation of personal suffering into compassionate service.

Alice Miller’s insights about gifted children becoming therapists illuminate this phenomenon. The sensitivity that made someone vulnerable to early wounding also equips them with extraordinary capacity for attunement and empathy. The therapist’s daimon often manifests as an intuitive understanding of others’ pain and the pathways toward healing.

However, this gift carries dangers. Therapists who haven’t adequately addressed their own wounds risk unconscious enactment, projection, and burnout. The daimonic calling to heal others must be balanced with ongoing attention to one’s own healing journey.

Integration: Parts-Based Therapies and the Multiplicity of Self

Contemporary parts-based therapies like Internal Family Systems (IFS) offer sophisticated frameworks for working with the daimonic dimension. These approaches recognize that what we call “self” contains multiple sub-personalities or parts, each with its own perspective and agenda.

In IFS terms, the “Self” (with a capital S) resembles the classical daimon—it is the core of compassionate, curious, confident presence that can heal and harmonize the various parts. Trauma creates exiled parts (carrying pain and vulnerability) and protective parts (managing and defending against that pain). The daimonic journey involves helping protective parts relax so exiled parts can be witnessed and healed, allowing the authentic Self to lead.

This multiplicity model helps explain why accessing the daimon is complex—we must navigate internal resistance, protection, and fear. It also offers hope: no matter how wounded or defended, the authentic Self remains intact and accessible.

Honoring the Daimonic Journey

The concept of the daimon, traced through these ten figures and contemporary neuroscience, reveals a consistent truth: within each person exists an authentic center that serves as both guide and goal of psychological healing. This center is paradoxical—simultaneously our most intimate self and something that transcends ego, the source of both our greatest gifts and our connection to primal wounds.

Understanding the daimon has profound implications for psychotherapy. It suggests that symptoms and suffering often contain daimonic significance—they may be distorted expressions of our authentic self seeking recognition. It reveals why the journey toward healing necessarily involves encountering our wounds—the daimon dwells in the same deep waters as our trauma.

The neuroscientific understanding of shared pathways between intuition and trauma offers both explanation and hope. It explains why accessing authenticity can be so challenging and triggering. But it also suggests that with careful attention, support, and practice, we can learn to differentiate between trauma responses and genuine inner guidance.

For therapists, recognizing the daimonic dimension transforms our work from symptom reduction to soul-making. We become midwives to authenticity, helping clients navigate the treacherous but ultimately liberating journey toward their true selves. This requires us to maintain our own daimonic connection, continuing our healing journey while serving others on theirs.

The daimon calls us beyond comfortable adaptation toward authentic expression, beyond mere healing toward wholeness, beyond survival toward creative living. In a world that often demands conformity and offers countless distractions from inner truth, honoring the daimonic dimension becomes both a personal imperative and a cultural necessity.

As we face collective challenges that require unprecedented creativity and authenticity, understanding and accessing our daimonic nature becomes ever more crucial. The wounded healer archetype suggests that our individual healing journeys are not merely personal but contribute to collective healing. By embracing our own daimonic path, we create space for others to do the same.

The journey toward the daimon is not for the faint of heart. It requires courage to face our wounds, discernment to differentiate truth from trauma, and persistence to keep following the thread of authenticity through life’s labyrinth. Yet as these ten figures demonstrate, this journey offers the possibility of not just healing but transformation—not just recovery but discovery of who we most deeply are and what we’re called to contribute.

In the end, the daimon represents both our most human and most divine aspect—the unique note we’re here to sound in the world’s symphony. Learning to hear and honor this inner voice, while navigating the wounds and defenses that obscure it, remains the central challenge and opportunity of human existence. Modern psychotherapy, informed by ancient wisdom and contemporary neuroscience, offers unprecedented tools for this essential journey. The question is not whether we have a daimon, but whether we have the courage to listen.

Bibliography

Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from Experience. London: Heinemann.

Bromberg, P. M. (2011). The Shadow of the Tsunami: And the Growth of the Relational Mind. New York: Routledge.

Corbett, L. (2011). The Sacred Cauldron: Psychotherapy as a Spiritual Practice. Wilmette, IL: Chiron Publications.

Damasio, A. (1999). The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and Archetype. Boston: Shambhala.

Eigen, M. (1998). The Psychoanalytic Mystic. London: Free Association Books.

Gendlin, E. T. (1978). Focusing. New York: Everest House.

Hillman, J. (1996). The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. New York: Random House.

Hollis, J. (2005). Finding Meaning in the Second Half of Life. New York: Gotham Books.

Jung, C. G. (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Vintage Books.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kalsched, D. (1996). The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit. London: Routledge.

Laing, R. D. (1960). The Divided Self. London: Tavistock Publications.

Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Levine, P. A. (2010). In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

McGilchrist, I. (2009). The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Miller, A. (1981). The Drama of the Gifted Child. New York: Basic Books.

Moore, T. (1992). Care of the Soul. New York: HarperCollins.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: Norton.

Perls, F., Hefferline, R., & Goodman, P. (1951). Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality. New York: Julian Press.

Plato. (2002). Apology. Trans. G.M.A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. New York: Norton.

Reich, W. (1945). The Function of the Orgasm. New York: Orgone Institute Press.

Renn, P. (2012). The Silent Past and the Invisible Present: Memory, Trauma, and Representation in Psychotherapy. New York: Routledge.

Romanyshyn, R. (2007). The Wounded Researcher: Research with Soul in Mind. New Orleans: Spring Journal Books.

Rumi, J. (1995). The Essential Rumi. Trans. Coleman Barks. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

Schore, A. N. (2003). Affect Regulation and the Repair of the Self. New York: Norton.

Schwartz, R. C. (1995). Internal Family Systems Therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Siegel, D. J. (2007). The Mindful Brain: Reflection and Attunement in the Cultivation of Well-Being. New York: Norton.

Stern, D. N. (2004). The Present Moment in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life. New York: Norton.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking.

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment. London: Hogarth Press.

Woodman, M. (1982). Addiction to Perfection: The Still Unravished Bride. Toronto: Inner City Books.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

0 Comments