All experience is past by definition. Tradition is transmission of past experience which has become knowledge and know-how. Thus, we can with reason conclude that without tradition, there can be no language, no philosophy, no science, no technique, art, or industry. Why should architecture be an exception?

– Leon Krier form Howard Roark: Defended Against His Admirers

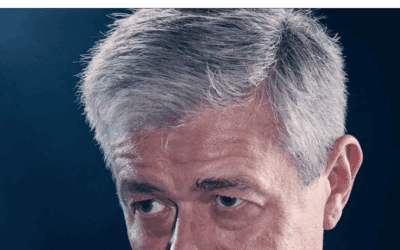

The Traditionalist Architect Who Built for the Future

Leon Krier 7 April 1946 – 17 June 2025

Leon Krier passed away this week, leaving behind a legacy that fundamentally challenged how we think about cities, communities, and the spaces we inhabit. As a depth psychotherapist, I’ve spent years exploring the depth psychological forces that shape our world. Krier was one of the first thinkers who helped me understand that architecture isn’t just about buildings. It’s about consciousness, politics, and the human condition itself.

Leon Krier’s philosophy uses architecture as a vehicle for cultural and political critique, particularly of modernism, suburban sprawl, and the industrialization of cities. His work became central to the New Urbanism movement and Traditionalist Architecture. The core tenets of his philosophy, often expressed provocatively, centered on a radical idea: architecture is political.

For Krier, architecture was inseparable from political and moral decisions. He believed that the built environment reflects a society’s values and power structures. The centralization and alienation of modernist city planning mirrors technocratic, often authoritarian systems. This wasn’t just academic theory. It was a lived conviction that informed every sketch, every design, every passionate argument he made throughout his career.

His critique of Modernism and functional zoning was particularly fierce. Krier denounced the principles of Modernist architecture, especially those promoted by Le Corbusier and CIAM with their separation of functions: work, life, leisure. He believed this led to soulless cities, loss of community, and environmental degradation. The “towers in the park” and isolated zoning, to him, reflected inhumane utopian ideologies. They treated humans as abstract units rather than embodied beings with deep needs for connection and place.

What particularly angered Krier about modernity was how it had stripped the common man of the ability to be an artist through common labor. His style was inherently empowering to labor. He was somebody who celebrated the blue collar workers who were supposed to build our spaces. He hated that this labor had been offshored, specialized, stripped of meaning and relationship to built environment. He hated that it had created a brain drain where people couldn’t have pride in their work and future potential trade artists were forced into advertising and email jobs. He the diminishing opportunities for the modern man to do something that was technical, skilled and creative for a middle class salary.

He thought the best places to build were places where this collective wisdom had not been lost. These were places where workers still had the ability to create craftsmen-like spaces. The architect could leave places in the specs for the tradesmen to riff and bring in their own creativity to the job. This was the older European tradesman ideal. When building castles, tradesmen weren’t just laborers but Master Craftsmen who had studied for years. They were allowed to elaborate and create their own patterns. They inserted timeless wisdom through creative solutions and added their own personality to the gargoyles they carved. Krier saw that modernity was making us stupid. It was making us reliant on systems that outsourced all of our labor. It also stripped us of our pride, our creativity, and our belief in our ability to be generative. We lost the ability to create new spaces and envision new worlds. We also lost the ability to take pride in simple labors and simple lives.

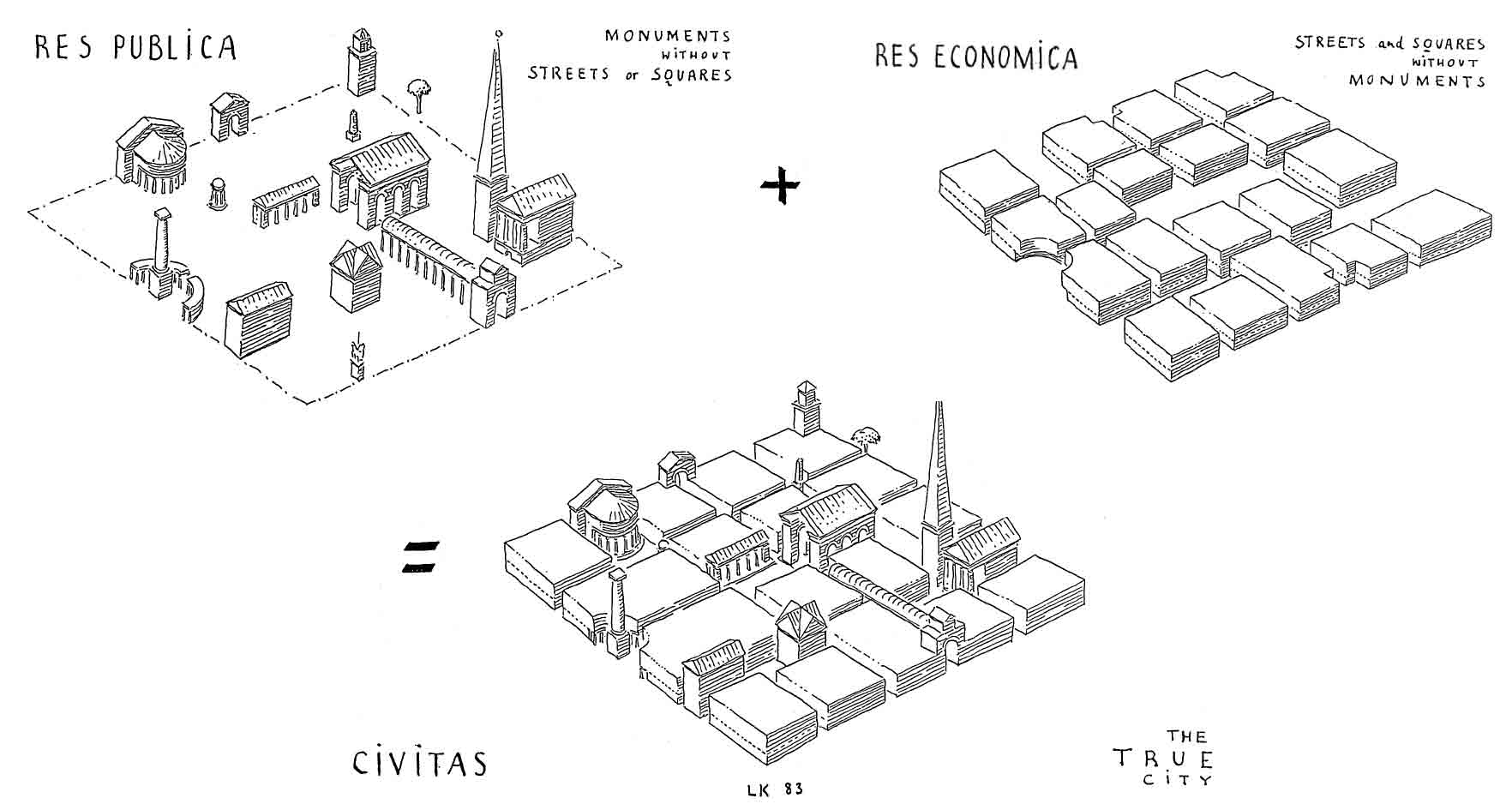

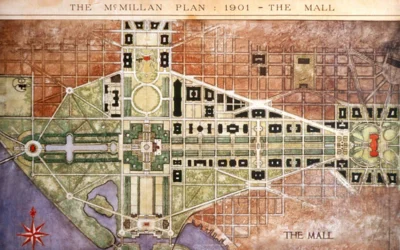

Instead of this alienating system, Krier advocated for human-scale urbanism with walkable, mixed-use, human-scaled towns with clearly defined public and private spaces. He supported compact cities, organized around a center and intuitively readable and navigable to their inhabitants. A city that required a GPS to navigate was a failure in Krier’s eye. Streets and squares, in his vision, should be designed for people, not cars. This wasn’t nostalgia. It was a recognition that certain forms of human settlement have endured because they work at a fundamental psychological and social level.

Early in my career, I was just a writer trying to connect all of the forces that are beneath our culture that manifest through different visual and sociological elements. I did a series on architecture and wrote about Leon Krier. I had no idea why a Luxembourg architect would be emailing me. But Krier saw the piece and reached out because he liked it so much and wanted to talk to me. The recording of that conversation was one of the first times I realized something important. It was easier to connect with the people who saw the same forces under the world that I did than I had ever imagined.

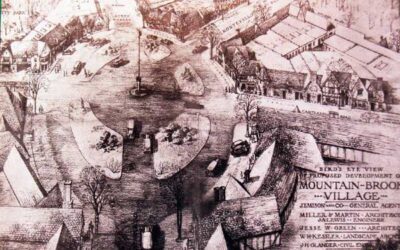

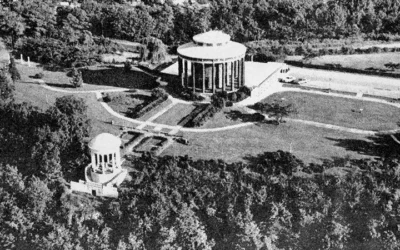

I grew up going to Seaside, Florida. I always felt so empowered as a kid because the community was not designed for cars. It was designed for people and bikes. I felt like I was finally in an element that allowed me to have the same autonomy of an adult. In Seaside while you were always stumbling upon secret pathways and shortcuts because it was designed for people as pedestrians. It was so creative and so intuitive to navigate. As a kid who didn’t have a good sense of direction and would get lost, I could always orient myself. I knew where I was. I didn’t know until years later that this was by design.

During the 1970s Oil Embargo, when it wasn’t known if oil and energy prices would ever come back down, Seaside was a forward-thinking community that was designed like older communities. It was based on the pre-existing architecture and the setting and place of Florida. landmarks and readable street systems told you where you were in relationship to the town. Old funky Florida fish houses with rusted tin roofs based on early European and American town planning principles was the original vision. Shopkeepers would live above or nearby their stores. The city would be navigable by car but designed for people to walk in a world with limited energy. It was designed along wind lines for a world, that may not have air conditioning, to open their windows for cross breeze and cross-conversation. It was designed to be incredibly effective and efficient. It was designed to last because it looked like the past and what had already lasted. I tell my patients in therapy that “the best indicator of future behavior is past behavior”. Certain elements of the past will always resurface inevitably in the future. Krier made a career finding those inevitable elements in architecture that could not be discarded. No matter how much modernists and the modern architecture moments tried to discard them and revision from scratch.

Seaside would be an integral testing ground for the New Urbanism movement being practicalized and replicated. This is a design philosophy that prioritizes walkable neighborhoods containing a diverse range of housing and job types. It sought to bring democratic ideals back to design. New Urbanism promotes increased density, traditional neighborhood structure, and sustainable development. There are many other places like Seaside now. But there weren’t in the early 1990s when I was a kid. It was one of the only liminal places I had ever been. I felt such an intuitive connection walking around and being able to just navigate it. This was a place built for me, a person. We forget how new, and frankly historically anomalous, all of these things that we have done to the modern world are. All these algorithmic, technocratic, consumerist, disposable, terrible, inhuman things really are not that old. To make a better future Krier wanted to take us back to the past.

New Urbanism is about building for people. Not for cars, not for profit, not for oil, not for corporations, not for real estate private equity, and definitely not for authoritarian control. It’s about building a place to re-empower the individual as the center of the universe. You know, like a community. Those things we used to have. I felt that as a kid in Seaside. All of Krier’s designs have something that you feel. They connect you to something bigger and older than yourself. They connect you to what all of architecture and the greater Art was supposed to point us back to. When I grew up, I wanted to understand these movements and the people responsible for them. This is what led me to learning about Leon Krier.

Krier’s rejection of industrial building typologies was absolute. He opposed the standardization and mechanization of building design and construction. Prefabrication and international styles, he argued, alienate people from place and history. Instead, Krier supported vernacular, craft-based traditions that reflect local climates and cultures.

This commitment to tradition and continuity wasn’t about nostalgia. Krier championed traditional architecture as a timeless language. He argued that classical and vernacular forms contain centuries of wisdom about proportion, symbolism, and function. Modern architecture, in contrast, often imposes newness for its own sake. It disregards continuity and memory.

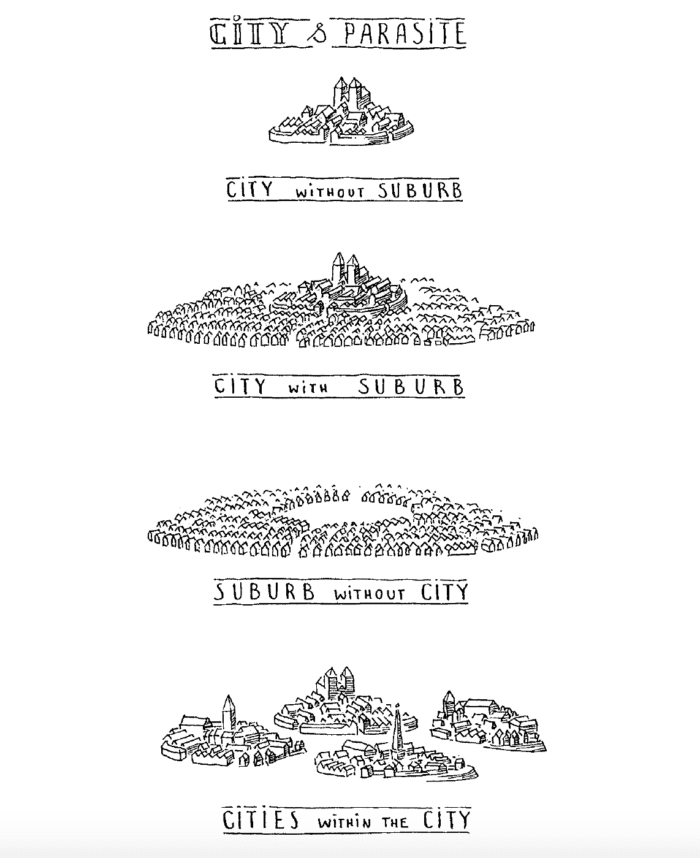

His city-town-village model proposed a hierarchical model of human settlements. From cities to towns to villages, each with appropriate density and civic life. This model promotes decentralization, autonomy, and subsidiarity in governance. It mirrors Aristotle’s idea of the polis as a moral and political unit.

For Krier, designing a building or city was a moral act. Urbanism should foster community, sustainability, and dignity. In this sense, the built environment is not neutral. It can liberate or oppress. He believed architects should serve the community, not corporations or abstract artistic ideals and myopic self expression through weird shapes. Architects’ work must be legible, beautiful, and enduring. The alienation caused by many modernist works was, for Krier, a betrayal of the architect’s social duty.

When Krier reached out I thought it was very odd that a Luxembourg architect who worked for the prince, now King, of England would be emailing a social worker in Alabama writing on a psychotherapy blog. I was really happy to have anybody pay attention to anything that I wrote. Let alone the person I was writing about who was famous. So I emailed Krier and he wanted to talk. The recordings of those were some of the beginnings of the podcast. They introduced this idea that I could do through conversation what I was trying to do through writing. I could connect \ psychology back to the study of consciousness and all of the human forms of expression it creates. The study of archetypes, the study of the primal forces that we’re communing with when we make art.

Krier’s design philosophy was incredibly political. He saw architecture as a kind of politics. That’s why he was so angry about it. He was kind of a difficult guy. He was irascible. He was frustrating. He was also deeply wounded and sensitive, having seen a world he grew up in be stripped of its humanity durring his lifetime.

I would trade authors with him often. He would give me book reviews and criticisms if he felt like I was reading something that was too modern. But modern to him was sometimes 100 years old. He got mad at me for sending him a book that included something that Martin Heidegger had written. One time when I emailed him poetry, I got this back as a response:

“I don’t read poetry at all now. Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine, Bourget, Cros, Hoelderlin, Pushkin, were my preferred authors when adolescent and when for 16 happy years I accompanied on the piano my french singer friend. When she didn’t move with me to the house I had built for her, poetry left my life. Just reading or replaying those pieces opens floods of tears.”

Krier was a very interesting man. I enjoyed having him as a pen-pal for a long time. I found in the Ghostbusters special features that the actor who plays Egon Spengler, Harold Ramis, had modeled his performance and appearance off of Leon Krier’s talks and I let him Krier know. “Makes sense” was all he said.

He told me about private conversations with Margaret Thatcher, debating what the aesthetic of the future should be. He also told me about his deep respect for all cultures that was apolitical. He saw design as a way to prevent and heal fascism and authoritarianism. He saw all forms of design that were authentic and beautiful as being an expression of that culture’s way of being. They were expressions of their need for structures to reflect their modes of existence.

He told me I reminded him of a Jungian analyst that he had met at Zurich once, James Hillman. Even though quite a compliment. I have long been afraid that many of James Hillman’s own worst angels are some of my own. I use Hillman’s hubris in many places to check myself. Krier told me that James Hillman had told him that European architecture draws the eye upward to seek heaven. All the lines in European architecture draw the eye towards the ceiling to aspire to God. But, Hillman had told Krier, American architecture puts in a drop ceiling and fluorescent lighting because it wants workers to stare downward into hell.

Krier worked in many styles. Something like Poundbury in England or work in Guatemala are very different. But they are in communion with a place. They mirror the history and the styles of the geography and setting. They try to recenter design on what makes place unique and what makes the people there special. In this way, I think that Krier was similar to some of the architects that he hated. More similar than he would like to know. Even though his results were very different, a lot of his working process and the axes that he sought to grind were similar to someone like Frank Lloyd Wright, even though Krier hated Wright.

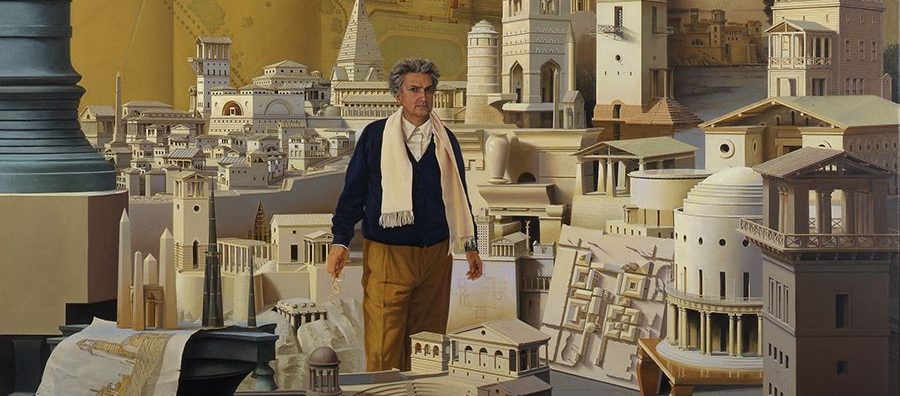

He showed me the diagrams that he had made of a house that Frank Lloyd Wright had drawn as a concept for Ayn Rand’s proposed studio. Krier corrected the Wright sketch and drew his own design of what the “right” version would have been of Wright’s drawing. It was these kind of quirks that I always found so endearing.

Seaside Florida was designed in the style of postmodern classicism. But Krier worked and handled many styles of architecture. What was essential to him was the archetype. The inborn form of how society had evolved space to reflect its needs and modes of being. Most of his designs echo more ornate styles with their detail stripped down to the archetypal functions of the structure.

I would send him pictures of my kids enjoying Seaside at the same age that I was when I found it. He would send me pictures from his hometown that inspired his designs. Things like recolored digitized grainy film footage of a man feeding a horse a sugar cube while it pulled a cart.

Krier hated oil. He hated modernism. He hated cheap consumption-driven culture that went along with it, like cars. Things designed not to be permanent. He saw the best architecture as something that sprung from a natural need that was timeless. Those needs would always be there wether or not architecture reflected and expressed them. He saw the changes that had happened to the world in his lifetime as something that was very bad. I would probably agree with him there, although I don’t agree with him on everything.

Krier worked under the assumption that form and structure are inseparable from function. But his style wasn’t purely functional. He developed an aesthetic around the interplay of how people used space and how you built the space. He didn’t like modern building techniques. He didn’t really like anything derived from oil at all. Which is almost everything we use to build now. He thought that cursed cheap energy source and the finance capital states it created were one of the biggest problems facing our world. It had driven it to ego and empire.

He was a kind man and interesting. We can learn a lot from the things that he thought. He was a huge fan of Hannah Arendt, (who funnily enough once had an extramarital affair with Heidegger). I think that was because Hannah Arendt saw echoes and reflections between politics and the cultural and aesthetic expressions around it.

What specifically appealed to Krier about Arendt’s “The Human Condition” was her threefold distinction between labor, work, and action. Krier saw “work” and “action” as the domains of architecture and urbanism. He believed Modernism had reduced architecture to mere “labor” or technical problem-solving. It ignored architecture’s role in facilitating meaningful public action and enduring civic life.

Arendt idealized the Greek polis as a structured, bounded public space where free individuals could appear before one another in speech and deed. Krier viewed the traditional city as a modern analogue to the polis. The square, the street, and the civic building were arenas for action. They were spaces for public life, dialogue, and shared identity. Modern urban planning, in his view, destroyed these spaces. It replaced them with highways, parking lots, strip malls and anonymous zoning.

Arendt warned of the rise of systems that reduce humans to cogs, governed not by politics but by “the social” and administration. Krier saw modern architecture as complicit in this trend. It served centralized bureaucracies, not communities. He felt that large-scale housing blocks, sterile planning, and the international style were the spatial expressions of totalitarian or technocratic ideologies. This view parallels Arendt’s critique of 20th-century politics.

Arendt saw how people feel designs that they don’t necessarily understand consciously. Leon Krier was a sort of a “depth” architect. He was working in communion with history and a depth psychology of using visual archetype, to anticipate the future. This is why his buildings are so future-forward. He was so angry at anyone who was building just for today, just for a dollar. He believed that spaces should be able to be disassembled, moved, renovated, and maintained. A building demolished 10 years later for a new style was a failure. Buildings should be a part of us. We should be in conversation with them.

The depth of Krier’s influence on contemporary urbanism cannot be overstated. Andrés Duany, another New Urbanist urban planner and architect, was another person that we interviewed on our podcast. Like all of the people in this movement, he spoke of how Krier inspired many people to look beyond a world where energy was free. Where labor was something that was a cheap commodity that could be offshored.

Krier’s unseen influence ripples through countless contemporary projects and movements. His students and followers have gone on to design communities across the world that prioritize human scale and traditional craft. Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, co-founder of DPZ with Duany, credits Krier with opening her eyes to the political dimensions of design. Stefanos Polyzoides, another leading New Urbanist, describes Krier as the philosophical backbone of the movement. He was the one who gave them the language to articulate what was wrong with modernist planning.

But his influence extends far beyond the New Urbanist circle. Architects like Robert A.M. Stern, though working in different contexts, have acknowledged Krier’s impact on their thinking about tradition and continuity. Even architects who disagreed with him found themselves having to grapple with his critiques. The Charter for the New Urbanism, adopted in 1996, reads like a practical application of Krier’s theoretical work.

His influence on the peak oil movement went beyond theory. He showed that traditional urbanism wasn’t just nostalgic but anticipatory. The old ways of building would become the new ways once the oil age ended. For the peak oil community, Krier provided both a critique of the present and a workable vision of the future. He demonstrated that the end of cheap oil didn’t have to mean the end of civilization. It could instead mean a return to more humane, sustainable ways of living together.

What’s remarkable is how many young architects, theorists, futurists, and planners discovered Krier’s work and found in it a vocabulary for their own dissatisfaction with the status quo. They saw in his drawings not just beautiful buildings but a comprehensive critique of how we’ve organized our society in opposition to our unchanging human psychology. His influence can be seen in the growing movement toward traditional building techniques. It’s in the revival of classical architecture education. It’s in the increasing skepticism toward top-down, technocratic planning.

The principles Krier championed have found their way into zoning reforms across the country. They’re in the form-based codes that are slowly replacing the segregated use zoning he so despised. When city planners today talk about “missing middle” housing or “gentle density,” they’re using concepts that Krier helped articulate decades ago. When developers build walkable mixed-use neighborhoods, whether they know it or not, they’re following patterns that Krier spent his life remembering, re-visioning, creating, and promoting.

Perhaps most importantly, Krier inspired a generation to think about architecture as more than aesthetics or function. He taught them to see it as fundamentally about human dignity and political freedom. This perspective has influenced not just how buildings are designed but how we think about public space, community engagement, and the right to the city.

Krier worked closely with developer Robert Davis to conceive and build Seaside during a particularly tenuous piece of history. The 1970s oil crisis had thrown the future of car-dependent development into question. Energy prices soared. The American dream of endless suburban sprawl suddenly seemed unsustainable. It was in this fraught moment that Davis and Krier saw an opportunity. Not for despair, but for re-imagining what American towns could be.

We are at a fraught piece of history again. Climate change, social isolation, political polarization, and economic uncertainty define our moment. There will be many more such moments in the future. Krier saw these not as bad points but as inevitable points in time. They were opportunities for creativity where we could revision what our world could be. We could stop accepting as normal all the destructive and inhuman elements that we have started to take for granted in the world we live in. We could demand better. But as Howard Beale yells in the 1976 film The Network, first we would have to get angry.

He wanted us to see how our choices in something as disconnected from psychology as architecture send reverberations through humanity’s collective soul and the future of our species. Every street we design, every building we construct, every community we plan is a statement about who we are and who we want to become. These choices echo through generations. They shape the consciousness of children who grow up in these spaces. They determine whether we live in isolation or community. Whether we move through the world as machines or as humans.

I felt these things at Seaside in the 90s. I know the name of the man whose influence I felt. But many do not and never will. They will feel him all the same. In every walkable street, in every human-scaled plaza, in every building that speaks to permanence rather than profitm motive and manipulative forms of control, Krier’s vision lives on. His influence permeates spaces where people gather, where children play safely, where neighbors know each other’s names. These are the quiet revolutions we need that change the world.

As we face climate change, social isolation, and the continued dominance of car-centric planning, Krier’s ideas feel more relevant than ever. His vision of walkable communities, local materials, and human-scaled development offers a path forward that addresses both environmental and psychological needs.

The pandemic showed us how crucial our immediate environments are to our well being. Krier understood this decades ago. The spaces we inhabit shape our consciousness, our relationships, and our possibilities for meaningful action in the world.

Leon Krier once summarized his ethos: “Architecture is a political act. It either serves the community or the bureaucracy and its bean counters. Neutrality is a myth.” This understanding that our built environment is never neutral is his greatest gift to us. It always embodies values and shapes behavior.

As psychotherapists, we understand that environment shapes psyche. As citizens, we must understand that architecture shapes politics. Krier showed us that these are not separate realms but interconnected aspects of the human condition.

His passing marks the end of an era. But his ideas live on in every walkable neighborhood. In every human-scaled development. In every architect who chooses community over profit. In remembering Leon Krier, we remember that another world is possible. One built for humans, not machines. For community, not isolation. For permanence, not profit.

The conversations I had with him became part of the foundation for our podcast. They taught me that the people shaping our world are often more accessible than we think. More importantly, they taught me that the intersection of psychology, politics, and place is where the real work of building a more human world begins.

In Krier’s view both structure and function could not be separated. The beauty of form grew from that fusion, not the other way around. Krier’s politics were not mine. But he points us back at something universal beneath politics. His politics was the extension of the apolitical nature of archetype. We could fight with them or embrace them but they spoke to us always. He speaks to us through the life and work he left behind still.

Krier’s vision wasn’t perfect. He could be difficult, semantically antagonistic, dogmatic even. But he was also deeply human. He was wounded by the destruction he saw around him and passionate about the possibility of repair. In that, he offers us not just an architectural philosophy but a way of being in the world. Attentive to beauty. Committed to community. Uncompromising in the belief that we deserve spaces that honor our full humanity.

The answer, as Krier knew, is always political. And it starts with the next building, the next street, the next choice we make about how we want to live together.

0 Comments