Who were Sidra and Hal Stone?

1.1. The Stones’ Journey from Traditional Analysis to Voice Dialogue

Hal and Sidra Stone, the creators of the innovative therapeutic modality known as Voice Dialogue, began their careers as traditional Jungian analysts. However, over time they grew discontent with what they perceived as the dryness and authoritarian aspects of classical analysis. They felt that the traditional model placed too much power in the hands of the analyst, fostering a hierarchical dynamic that could hinder the patient’s autonomy and self-discovery.

Inspired by the work of other post-Jungian pioneers like Arnold Mindell, who emphasized the importance of somatic and experiential approaches, the Stones set out to develop a new modality that would be more collaborative, embodied, and empowering for the patient. They wanted to create a therapeutic process that would honor the multiplicity of the psyche and provide a direct, visceral way of engaging with its various parts or selves.

1.1.1 More Resources on the Stones and Voice Dialogue

Official Website: Voice Dialogue International

- Books: Embracing Our Selves Amazon

- YouTube Lecture: Voice Dialogue with Sidra and Hal Stone

- Interview: In Conversation with the Stones

- Podcast: Voice Dialogue Explained

- Article: Voice Dialogue and Psychotherapy

- Institute: Voice Dialogue Training

- Research: Publications on Voice Dialogue

- Quotes: Sidra Stone Quotes

- Lecture Series: The Stones’ Voice Dialogue Series

1.2. The Birth of Voice Dialogue

Out of this intention, Voice Dialogue was born. At its core, Voice Dialogue is a method for contacting, learning about, and developing a relationship with the many sub-personalities or selves that make up the psyche. These selves, the Stones believed, are not mere abstractions but vital, semi-autonomous entities with their own unique perspectives, feelings, and agendas.

In a Voice Dialogue session, the therapist guides the patient in giving voice to these various selves, allowing each to speak and express itself fully. The patient is invited to physically move between different chair positions as they embody each self, fostering a tangible sense of shifting identities. Through this process, the patient gains insight into the inner dynamics and conflicts between their selves, and begins to develop a more conscious, choiceful relationship with them.

The Stones saw Voice Dialogue not as a replacement for traditional analysis but as a powerful adjunct to it – a way of experientially enlivening the exploration of the psyche. They found that by directly engaging the selves in this way, patients could quickly access deep layers of material that might otherwise remain hidden or intellectualized. The work was often intense, cathartic, and transformative, leading to significant breakthroughs and shifts in self-understanding.

1.3. The Influence of Post-Jungian Thought

While the Stones drew heavily from Jung’s concept of the fragmented psyche, they also incorporated ideas from other depth psychologies and spiritual traditions. They were particularly influenced by the work of transpersonal theorists like Ken Wilber and Stanislav Grof, who emphasized the importance of integrating the full spectrum of human experience – from the personal to the archetypal to the mystical.

The Stones saw Voice Dialogue as a way of facilitating this kind of integration. By giving space for all of the selves to be heard and honored, even the most shadowy or marginalized ones, the work could help the patient to reclaim disowned aspects of their being and move towards greater wholeness. At the same time, by fostering a witnessing consciousness that could hold the multiplicity of selves with compassion and clarity, Voice Dialogue could also serve as a pathway to spiritual awakening and the realization of the transpersonal Self.

In this sense, the Stones’ work represents an important bridge between classical Jungian analysis and the more expansive, integrative visions of contemporary transpersonal psychology. It offers a powerful set of tools for navigating the complex, multidimensional landscape of the psyche, while also pointing towards the ultimate unity and transcendence at the heart of the human experience.

-

Key Concepts and Principles

-

2.1. The Multiplicity of the Psyche

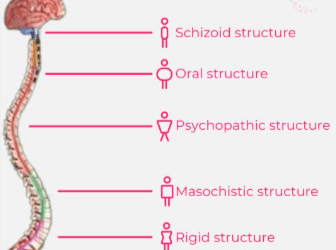

Central to the Stones’ work is the idea that the psyche is not a unitary entity but a multiplicity of selves or sub-personalities. These selves are seen as discrete centers of thought, feeling, and behavior that have evolved over the course of a person’s life in response to various biological, familial, and cultural factors.

Some of these selves may be dominant, well-developed, and consciously embraced by the ego, while others may be subordinate, underdeveloped, or disowned. Some may work harmoniously together, while others may be in conflict or competition with each other. The overall landscape of the psyche, in the Stones’ view, is one of dynamic diversity, with different selves coming to the fore in different contexts and stages of life.

This multiplicity, while potentially confusing or overwhelming at times, is not seen as inherently pathological. Rather, it is viewed as a natural and even necessary aspect of the psyche’s functioning. Each self has its own unique gifts, skills, and role to play in the overall ecology of the personality. The goal of Voice Dialogue is not to eliminate or merge the selves but to help them to differentiate, communicate, and collaborate more effectively.

2.2. The Aware Ego

A key aim of Voice Dialogue is the development of what the Stones call the Aware Ego – a centered, witnessing consciousness that can observe and engage the various selves without being identified with any one of them. The Aware Ego is not another self but a space of clarity and choice that emerges through the process of self-exploration and integration.

As the patient learns to separate from and dialogue with their different selves, they begin to dis-embed from their habitual identifications and reactions. They start to experience themselves as the one who is aware of the selves, rather than as any particular self. This shift in perspective can be profoundly liberating, allowing for greater flexibility, spontaneity, and responsiveness in one’s interactions with the world.

The Aware Ego, as it matures, takes on the role of an inner facilitator or conductor, orchestrating the various selves and helping them to work together harmoniously. It does not seek to control or dominate the selves but to create a space of open, respectful dialogue between them. It is the part of the psyche that can hold the tension of opposites, embrace paradox, and navigate complexity with grace and wisdom.

2.3. The Dance of Selves

The Stones use the metaphor of the dance to describe the fluid, dynamic interplay of selves in the psyche. Just as in a dance, the different selves must learn to move together in a coordinated way, alternately leading and following, asserting and yielding, expressing and listening.

In any given moment, one or more selves may take the lead, coming to the foreground of consciousness and directing the flow of energy and attention. Other selves may recede into the background, serving as support or counterpoint to the dominant ones. As the dance unfolds, the selves may switch roles, with previously subordinate ones coming forward and previously dominant ones stepping back.

The goal of Voice Dialogue is to bring more consciousness and skill to this dance of selves. By getting to know the different selves and their preferred steps, the patient can learn to move between them with greater ease and intentionality. They can become a more versatile and responsive dancer, able to adapt to changing circumstances and to express the full range of their being.

At the same time, the practice of Voice Dialogue can also help to identify and transform patterns of self-interaction that may be limiting or destructive. Selves that have been chronically suppressed or exiled can be invited back into the dance, while selves that have been overused or misused can be gently encouraged to step back and find a new role. Through this process of re-choreographing the inner dance, old wounds can be healed, new potentials can be realized, and a greater sense of wholeness and vitality can emerge.

-

The Practice of Voice Dialogue

-

3.1. Setting the Stage

A Voice Dialogue session typically begins with the therapist and patient sitting facing each other, with one or more empty chairs placed to the side. These chairs serve as “homes” for the different selves that will be invited to speak during the session.

The therapist may start by explaining the basic principles and process of Voice Dialogue, emphasizing that the work is a collaborative exploration and that the patient is always in charge of how far and deep they want to go. The patient is encouraged to approach the work with curiosity, openness, and self-compassion, and to let go of any judgments or expectations they may have about what is supposed to happen.

3.2. Identifying the Selves

The first step in a Voice Dialogue session is to identify the different selves that are present and active in the patient’s psyche. This can be done in a variety of ways, depending on the patient’s presenting issues and the flow of the session.

The therapist may ask the patient to describe a recent situation or interaction that was particularly charged or challenging for them. As the patient speaks, the therapist listens for the different voices or perspectives that emerge, and may reflect these back to the patient: “It sounds like there’s a part of you that feels really angry about what happened, and another part that feels scared and wants to hide. Is that right?”

Alternatively, the therapist may invite the patient to do a “self-inventory,” listing out the various roles, identities, and sub-personalities they are aware of in themselves. These might include archetypal roles like the Caregiver, the Warrior, or the Rebel; emotional states like the Angry One or the Sad One; or inner figures like the Inner Child or the Inner Critic.

As the selves are identified, the therapist may ask the patient to give each one a name and to describe its key characteristics, feelings, and motivations. This helps to concretize and personify the selves, making them more tangible and relatable.

3.3. Separating from the Selves

Once the relevant selves have been identified, the therapist guides the patient in separating from them and inviting them to speak. This is typically done by having the patient physically move to one of the empty chairs, taking on the posture and energy of the self being addressed.

The therapist may say something like, “Okay, let’s have you move to the other chair and become the Angry One. Can you feel that energy in your body? How does the Angry One sit? What does its voice sound like?”

As the patient inhabits the self, the therapist encourages them to speak from its perspective, using the first person: “I am the Angry One. I feel so frustrated and powerless. I just want to lash out and make them pay attention to me!”

The therapist may ask questions to help draw out the self’s experience and perspective: “How long have you been feeling this way? What do you need that you’re not getting? What would you like to say to the other selves?”

3.4. Facilitating Dialogue

As the session unfolds, the therapist facilitates a dialogue between the different selves that have been identified. This may involve having the patient move back and forth between chairs, giving voice to each self in turn and allowing them to respond to each other.

For example, if the Angry One has had a chance to speak, the therapist may then invite the patient to move to another chair and become the Scared One: “Let’s check in with the part of you that feels scared. Can you give it a voice? What does it want to say to the Angry One?”

As the selves speak and listen to each other, the therapist helps to create a space of open, non-judgmental curiosity and respect. The goal is not to have one self “win” over the others but to allow each to express its truth and to be heard and understood by the others.

Through this process of dialogue, the selves may begin to reveal their deeper needs, fears, and desires. They may also start to negotiate and collaborate with each other, finding new ways of relating and cooperating. The therapist supports this process by reflecting back key insights, facilitating communication, and encouraging the selves to experiment with new behaviors and interactions.

3.5. Integrating the Work

As the session draws to a close, the therapist helps the patient to integrate the insights and experiences they have had. This may involve summarizing key themes or breakthroughs, identifying areas for further exploration, or suggesting homework exercises to continue the work between sessions.

The therapist may also guide the patient in practicing the Voice Dialogue process on their own, using inner imagery or journaling to connect with their selves and facilitate inner conversations. Over time, as the patient becomes more skilled in this inner work, they may find that the selves naturally begin to communicate and collaborate more fluidly, even outside of formal therapy sessions.

Ultimately, the goal of Voice Dialogue is not just to have interesting conversations with one’s selves but to translate the insights and awarenesses gained into real changes in one’s life. As the patient becomes more adept at recognizing and working with their different selves, they may find that they have more choice and flexibility in how they respond to challenges and opportunities. They may feel more whole, more alive, and more authentically themselves, even as they embrace the diversity within.

-

Case Studies and Applications

-

4.1. Working with Inner Conflict: Sarah’s Story

Sarah came to therapy feeling torn between her desire to pursue her dream of becoming an artist and her sense of obligation to her family and their expectations of her. She felt like she was constantly at war with herself, with one part of her yearning for freedom and creative expression, and another part fearing disapproval and insecurity if she were to break away from the established path.

In their Voice Dialogue work, Sarah and her therapist identified several key selves that were involved in this conflict. There was the “Dreamer,” who longed to immerse herself in her art and follow her passions; the “Responsible One,” who felt duty-bound to meet her family’s needs and uphold their values; and the “Fearful One,” who was terrified of the risks and uncertainties of the artist’s life.

As each of these selves had a chance to speak and be heard, Sarah began to gain a clearer understanding of their different perspectives and needs. The Dreamer helped her to connect with her deep love of art and her authentic desire for self-expression. The Responsible One reminded her of the importance of honoring her commitments and considering the impact of her choices on others. And the Fearful One revealed the underlying anxieties and insecurities that were holding her back from taking bold steps.

Through the dialogue process, these selves began to find new ways of relating to each other. The Dreamer and the Responsible One realized that they shared a common value of meaningful contribution, and began to explore how Sarah could pursue her art in a way that also allowed her to give back to her family and community. The Fearful One, as it felt seen and understood by the other selves, began to relax its grip and trust in Sarah’s ability to handle the challenges of the artist’s path.

As Sarah continued to work with these selves and integrate their insights, she found herself feeling more clear and confident in her decisions. She enrolled in an art program and began to build a portfolio, while also finding ways to stay connected and supportive of her family. While the old conflicts still arose at times, Sarah now had a way of engaging them with curiosity and compassion, rather than getting caught in their tug-of-war. She felt more whole and true to herself, even as she navigated the complexities of honoring her different needs and roles.

4.2. Embracing the Shadow: Mark’s Journey

Mark sought out therapy because of a pervasive sense of emptiness and disconnection in his life. Despite having a successful career and a stable family, he felt like he was just going through the motions, cut off from any real sense of vitality or purpose. He was also aware of a deep well of anger and resentment within himself that he didn’t know how to express or deal with.

In his Voice Dialogue work, Mark encountered a number of selves that had been exiled or disowned in his psyche. There was the “Wild One,” a part of him that yearned for adventure, spontaneity, and raw, unbridled expression; the “Vulnerable One,” a tender, sensitive part that felt deeply wounded by early experiences of rejection and criticism; and the “Rageful One,” a fierce, primal part that carried all of Mark’s unexpressed anger and aggression.

As these selves emerged and were given voice, Mark initially felt a great deal of fear and resistance. He had spent so long trying to keep these parts of himself hidden and under control, fearing that they would overwhelm or destroy him if they were let out. The Wild One felt dangerous in its impulsivity, the Vulnerable One felt weak and exposing, and the Rageful One felt toxic and unacceptable.

But as Mark continued to engage these selves with the support of his therapist, he began to see them in a new light. He realized that the Wild One carried a vital energy and passion that had been missing in his life, and that it could be channeled in healthy, creative ways. He discovered that the Vulnerable One held the key to his capacity for deep connection and empathy, and that by embracing it he could start to heal his old wounds. And he found that the Rageful One, when given a safe outlet, could be a powerful force for assertiveness and boundary-setting, rather than a destructive liability.

Integrating these shadow selves was a gradual and sometimes challenging process for Mark. It required him to confront long-buried fears and pains, and to take risks in expressing sides of himself that felt unfamiliar or exposing. But as he did so, he began to feel a new sense of wholeness and authenticity emerging. He found himself more able to be present and engaged in his life, more connected to his own depths and to others. While the journey was ongoing, Mark now felt like he had a map and a compass for navigating the full landscape of his being.

4.3. Navigating Life Transitions: Emily’s Transformation

Emily came to therapy in the midst of a major life transition – she had recently retired from a long career, her children had grown and left home, and she was struggling to find a new sense of identity and purpose. She felt lost and adrift, unsure of who she was or what she wanted outside of the roles and routines that had defined her for so long.

In her Voice Dialogue work, Emily encountered a cast of selves that had played key roles in her life up until this point. There was the “Caregiver,” who had poured so much of herself into nurturing and supporting her family; the “Achiever,” who had driven her to succeed and excel in her career; and the “Responsible One,” who had kept everything running smoothly and held it all together. As Emily separated from these selves and let them speak, she realized how much of her sense of self had been tied up in these roles. Without them, she felt unmoored and unsure of who she was.

But as the work continued, other selves began to emerge from the shadows – selves that had been waiting in the wings, yearning for their time to shine. There was the “Explorer,” a curious, adventurous part that wanted to discover new places and try new things; the “Creative One,” a playful, imaginative part that longed to express itself freely; and the “Spiritual Seeker,” a contemplative, introspective part that yearned for deeper meaning and connection.

As Emily made space for these selves and started to engage them, she felt a new sense of excitement and possibility awakening within her. She realized that this transition, while disorienting, was also an opportunity – a chance to reconnect with neglected parts of herself and to craft a new chapter in her life. With the Explorer and the Creative One as her guides, she began to experiment with new hobbies and interests, from painting to travel to volunteering. And with the Spiritual Seeker as her companion, she delved into practices of meditation, reflection, and self-inquiry, seeking a deeper understanding of her place and purpose in the larger web of life.

Through this process, Emily began to develop a new, more expansive sense of identity – one that wasn’t dependent on any particular role or achievement, but that flowed from a deeper connection to her own essence and to the world around her. She still honored and appreciated the selves that had carried her through her earlier life, but she no longer felt defined or limited by them. She had discovered a new freedom and flexibility to be and become herself, in all her fullness and complexity.

The Evolution of Voice Dialogue

5.1. Hal and Sidra Stone’s Legacy

Over the course of their careers, Hal and Sidra Stone continued to develop and refine the practice of Voice Dialogue, both through their own clinical work and through training and collaborating with other therapists. They founded the Voice Dialogue Institute, which became a hub for teaching and research on the modality, and authored several influential books, including “Embracing Our Selves,” “Partnering,” and “The Shadow King.”

The Stones’ work had a significant impact on the field of psychotherapy, particularly within the Jungian and transpersonal communities. They helped to popularize the idea of the multiplicity of the psyche and the value of working directly with sub-personalities or parts. They also brought a new level of creativity, spontaneity, and embodiment to the therapeutic process, emphasizing the importance of experiential exploration and enactment.

At the same time, the Stones were committed to making their work accessible and applicable beyond the therapy room. They taught Voice Dialogue to couples, families, and groups, and developed applications for using the work in areas like education, business, and social change. They saw the modality not just as a tool for individual healing but as a way of fostering more conscious, compassionate relationships and communities.

5.2. Tamar Stone and the Evolution of Voice Dialogue

In the later years of their work, the Stones began to collaborate more closely with their daughter, Tamar Stone, who had grown up steeped in the world of Voice Dialogue and had become a skilled practitioner and teacher in her own right. Tamar brought a new generation’s perspective to the work, as well as a deep commitment to integrating somatic, emotional, and spiritual dimensions.

Under Tamar’s leadership, the Voice Dialogue Institute continued to evolve and expand its reach. She developed new applications of the work, such as using Voice Dialogue in executive coaching, leadership development, and social justice contexts. She also created programs and retreats that combined Voice Dialogue with other modalities like mindfulness, breathwork, and expressive arts, creating immersive experiences of self-discovery and transformation.

One of Tamar’s key contributions was to bring a more explicit focus on the body and the felt sense into the practice of Voice Dialogue. Drawing on her training in somatic therapies and mindfulness practices, she emphasized the importance of tuning into the physical sensations, impulses, and energies that arise when working with different selves. She saw the body as a direct pathway into the unconscious, and a powerful tool for integrating and transforming the insights gained through the dialogue process.

Tamar also brought a strong social and cultural consciousness to her work, exploring how issues of power, privilege, and oppression can shape the internal landscape of the psyche. She developed ways of using Voice Dialogue to help people identify and work with internalized voices of marginalization or dominance, and to cultivate more inclusive, liberatory forms of selfhood and relationship.

5.3. Voice Dialogue Today and Beyond

Today, Voice Dialogue continues to be a vital and evolving force in the world of psychotherapy and personal growth. Practitioners around the world are using the modality in a wide range of contexts, from individual and couples therapy to organizational consulting and social change work. The Voice Dialogue Institute, now under the leadership of a new generation of teachers and trainers, continues to be a source of innovation and learning in the field.

One of the key frontiers of exploration in contemporary Voice Dialogue is the integration of the work with insights from neuroscience, trauma studies, and interpersonal neurobiology. Practitioners are looking at how the dialogue process can help to rewire neural pathways, heal attachment wounds, and foster greater integration and resilience in the brain and nervous system. They are also exploring how Voice Dialogue can be used to work with collective and intergenerational trauma, helping to transform patterns of harm and disconnection that can be passed down through families and communities.

Another area of growth is the application of Voice Dialogue to larger systems and structures, from organizations and institutions to societies and cultures. By bringing awareness to the different voices and roles that shape these systems, and facilitating dialogue and collaboration between them, Voice Dialogue practitioners are helping to create more conscious, inclusive, and adaptive collectives. They are using the work to address issues like organizational change, social inequality, and environmental sustainability, and to foster more generative forms of leadership and citizenship.

At its core, Voice Dialogue remains a powerful tool for self-discovery, self-acceptance, and self-transformation. It invites us to embrace the full complexity and diversity of our being, to listen deeply to all the parts of ourselves, and to find new ways of living and relating that honor our wholeness. As the world continues to change and evolve, the need for this kind of inner work feels more urgent and necessary than ever. The legacy of Hal and Sidra Stone, carried forward by Tamar and so many others, offers a vital map and compass for navigating the landscape of the soul in these times of great transition and possibility.

Legacy of the Stones

6.1. The Stones’ Vision and Impact

The work of Hal and Sidra Stone represents a significant evolution in the field of depth psychology, one that has had far-reaching impacts on the theory and practice of psychotherapy. By developing the modality of Voice Dialogue, they offered a powerful new tool for exploring and integrating the multiple dimensions of the psyche, one that honored the complexity and creativity of the inner world.

The Stones’ vision was rooted in a deep respect for the wisdom and autonomy of each individual self or sub-personality. Rather than seeking to eliminate or control these selves, they invited a process of inner democracy, in which all voices could be heard and valued. They saw the goal of therapy not as the achievement of a static state of wholeness, but as the development of a dynamic, fluid relationship between the different parts of the psyche.

This vision had profound implications for the therapeutic relationship itself. Rather than positioning the therapist as an expert or authority figure, the Stones saw therapy as a collaborative partnership, in which both therapist and client were engaged in a mutual process of exploration and discovery. They emphasized the importance of the therapist’s own inner work and self-awareness, and the need for a stance of openness, curiosity, and compassion in working with the client’s selves.

Beyond the therapy room, the Stones’ work had a significant impact on the larger culture, helping to popularize the idea of the multiplicity of the self and the value of embracing diverse inner experiences. Their books and teachings reached a wide audience, and their ideas have been taken up and applied in fields ranging from education and business to politics and social change.

6.2. The Continuing Relevance of Voice Dialogue

As the world continues to face complex challenges and transformations, the wisdom and tools of Voice Dialogue feel more relevant and necessary than ever. In a time of increasing polarization and fragmentation, both within and between individuals and groups, Voice Dialogue offers a way of fostering greater understanding, empathy, and collaboration across differences.

By learning to recognize and engage the different selves within us, we can develop a more flexible and adaptive sense of identity, one that is not rigidly attached to any particular role or perspective. We can learn to hold the tension of opposites, to embrace paradox and uncertainty, and to find creative solutions that honor the needs and gifts of all our parts.

At the same time, Voice Dialogue can help us to identify and transform patterns of power and oppression that may be operating within our own psyches and relationships. By bringing awareness to internalized voices of dominance or marginalization, and facilitating dialogue and reconciliation between them, we can begin to create more just and equitable ways of being and relating.

In a world facing ecological crisis and the need for profound systemic change, Voice Dialogue also offers a tool for cultivating the kind of leadership and citizenship that can rise to the challenge. By learning to access and integrate the diverse capacities and perspectives within us, we can develop the flexibility, resilience, and creativity needed to navigate complex challenges and forge new paths forward.

6.3. Honoring the Stones’ Legacy

As we look to the future of psychology and human development, the legacy of Hal and Sidra Stone serves as an enduring source of inspiration and guidance. Their lifework stands as a testament to the power and potential of the human spirit, and to the transformative possibilities that emerge when we have the courage to embrace our full, messy, complex humanity.

By carrying forward their vision and tools, and continuing to evolve and adapt them to meet the needs of our time, we can honor the profound gift that the Stones have given to the world. We can create a psychology that is truly in service to the wholeness and awakening of all beings, and that supports us in co-creating a future of greater connection, creativity, and compassionate understanding.

May the work of Hal and Sidra Stone continue to ripple out in the world, touching lives and communities in ways we can scarcely imagine. And may we each find the courage and curiosity to embark on our own journeys of self-discovery and transformation, trusting in the wisdom and resilience of the many selves that make us who we are.

Further Reading:

1. Assagioli, R. (1965). Psychosynthesis: A Manual of Principles and Techniques. Hobbs, Dorman & Company.

2. Berne, E. (1961). Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy. Grove Press.

3. Hermans, H. J. M., & Gieser, T. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of Dialogical Self Theory. Cambridge University Press.

4. Perls, F., Hefferline, R., & Goodman, P. (1951). Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality. Julian Press.

5. Rowan, J., & Cooper, M. (Eds.). (1998). The Plural Self: Multiplicity in Everyday Life. SAGE Publications.

6. Schwartz, R. C. (2001). Introduction to the Internal Family Systems Model. Trailheads Publications.

7. Watkins, H. H. (1993). Ego-State Therapy: An Overview. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 35(4), 232-240.

List of Publications by Hal and Sidra Stone:

1. Stone, H., & Stone, S. (1989). Embracing Our Selves: The Voice Dialogue Manual. New World Library.

2. Stone, H., & Stone, S. (1993). Embracing Your Inner Critic: Turning Self-Criticism into a Creative Asset. HarperOne.

3. Stone, H., & Stone, S. (1998). You Don’t Have to Write a Book!: An Easy-to-Follow Guide to Writing, Editing, Publishing and Promoting. Delos, Inc.

4. Stone, H., & Stone, S. (2000). Partnering: A New Kind of Relationship. New World Library.

5. Stone, S. (2005). The Shadow King: The Invisible Force That Holds Women Back. Backinprint.com.

6. Stone, S., & Stone, H. (2007). The Inner Critic Advantage: Making Peace With the Noise in Your Head. Delos, Inc.

Timeline of Hal and Sidra Stone’s Life and Work:

1. 1927: Hal Stone is born.

2. 1936: Sidra Stone (née Winkelman) is born.

3. 1948: Hal Stone graduates from UCLA with a bachelor’s degree in psychology.

4. 1953: Hal Stone receives his Ph.D. in clinical psychology from UCLA.

5. 1960s: Hal Stone begins his private practice as a clinical psychologist and Jungian analyst in Los Angeles.

6. 1970: Hal and Sidra Stone meet and begin their personal and professional relationship.

7. 1972: Hal and Sidra Stone marry.

8. 1970s: The Stones develop the Voice Dialogue process and begin teaching it to others.

9. 1978: The Stones co-found the Center for the Healing Arts in Los Angeles, where they teach Voice Dialogue and other transformational tools.

10. 1985: The Stones publish their first book, “Embracing Our Selves: Voice Dialogue Manual,” under the name Hal Stone and Sidra Winkelman.

11. 1989: The Stones publish “Embracing Our Selves: The Voice Dialogue Manual,” a revised and expanded edition of their first book.

12. 1993: The Stones publish “Embracing Your Inner Critic: Turning Self-Criticism into a Creative Asset.”

13. 2000: The Stones publish “Partnering: A New Kind of Relationship.”

14. 2007: The Stones publish “The Inner Critic Advantage: Making Peace With the Noise in Your Head.”

15. 2009: Sidra Stone publishes “The Shadow King: The Invisible Force That Holds Women Back.”

16. 2020: Hal Stone passes away at the age of 93.

17. Present: Sidra Stone continues to teach and promote Voice Dialogue through workshops, trainings, and publications. Tamar Stone, their daughter, also continues to advance the work of Voice Dialogue.

Bibliography:

Bly, R., & Woodman, M. (1998). The Maiden King: The Reunion of Masculine and Feminine. Henry Holt and Company.

Dyak, M. (2012). The Voice Dialogue Facilitator’s Handbook, Part 1: A Step-by-Step Guide to Working with the Aware Ego, Selves, and the Voice Dialogue Process. L.I.F.E. Energy Press.

Dyak, M. (2013). The Voice Dialogue Facilitator’s Handbook, Part 2: Advanced Tools for Professionals. L.I.F.E. Energy Press.

Firman, J., & Gila, A. (2002). Psychosynthesis: A Psychology of the Spirit. SUNY Press.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1971). Psychological Types (H. G. Baynes, Trans.). Princeton University Press.

Mindell, A. (2000). Dreaming While Awake: Techniques for 24-Hour Lucid Dreaming. Hampton Roads Publishing.

Mindell, A. (2010). ProcessMind: A User’s Guide to Connecting with the Mind of God. Quest Books.

Rowan, J. (1993). Discover Your Subpersonalities: Our Inner World and the People in It. Routledge.

Rowan, J. (2005). The Transpersonal: Spirituality in Psychotherapy and Counselling (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Schwartz, R. C. (1997). Internal Family Systems Therapy. Guilford Press.

Stone, H., & Stone, S. (1989). Embracing Our Selves: The Voice Dialogue Manual. New World Library.

Stone, H., & Stone, S. (1993). Embracing Your Inner Critic: Turning Self-Criticism into a Creative Asset. HarperOne.

Stone, H., & Stone, S. (2000). Partnering: A New Kind of Relationship. New World Library.

Stone, H., & Winkelman, S. (1985). Embracing Our Selves: Voice Dialogue Manual. Nataraj Publishing.

Stone, S. (2005). The Shadow King: The Invisible Force That Holds Women Back. Backinprint.com.

Stone, S., & Stone, H. (2007). The Inner Critic Advantage: Making Peace With the Noise in Your Head. Delos, Inc.

Stone, T. (2012). Embracing Our Selves: The Voice Dialogue Manual for Facilitators. Voice Dialogue International.

Watkins, J. G., & Watkins, H. H. (1997). Ego States: Theory and Therapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Whitmont, E. C., & Kaufmann, T. (2017). Psyche and Substance: Essays on Homeopathy in the Light of Jungian Psychology. North Atlantic Books.

Wilber, K. (2000). Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy. Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2007). The Integral Vision: A Very Short Introduction to the Revolutionary Integral Approach to Life, God, the Universe, and Everything. Shambhala.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

The Symbolism of the Bollingen Stone

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

The Symbolism of Color in Dreams

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jung to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

The Origins and History of Consciousness

Jung’s Empirical Phenomenological Method

The Future of Jungian Thought

Jungian Analysts

0 Comments