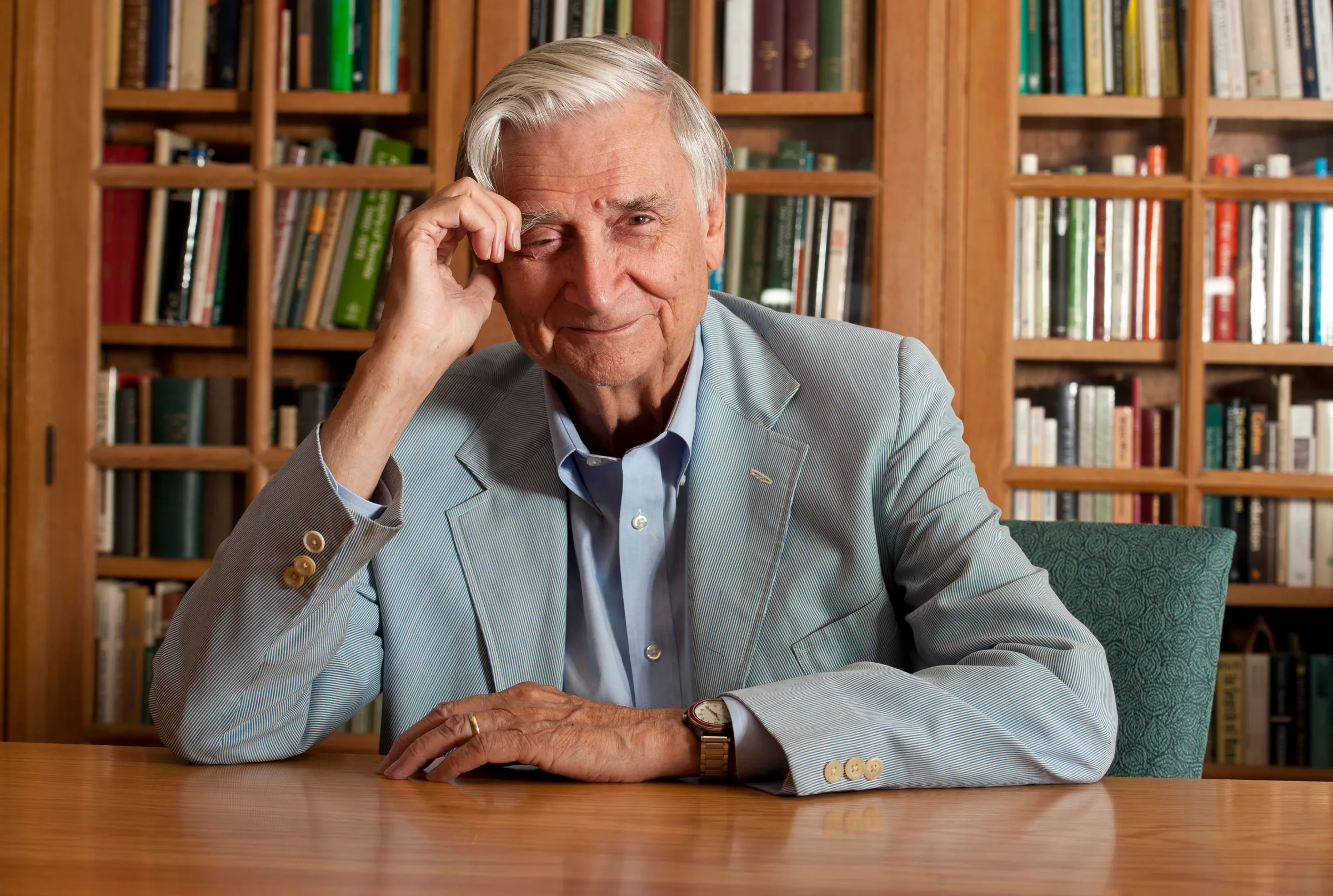

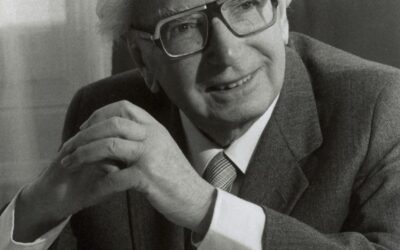

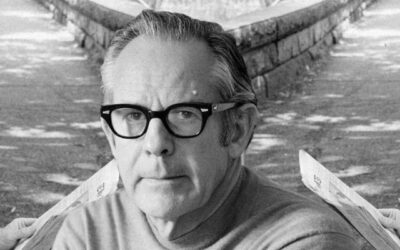

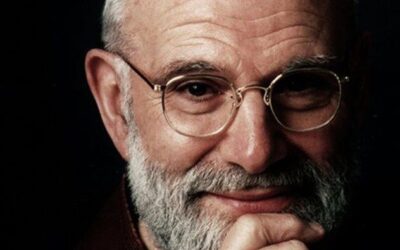

Who was Edward O Wilson?

Edward O. Wilson (1929-2021) was a pioneering American biologist, naturalist, and writer who made seminal contributions to the fields of ecology, evolution, and sociobiology. As one of the most influential scientists of the late 20th century, Wilson helped to transform our understanding of the natural world and the complex relationships between organisms and their environments. Over his long and prolific career, he authored over 30 books and hundreds of scientific papers, earning numerous accolades including two Pulitzer Prizes.

Wilson is best known for his groundbreaking work on the biology of ants and other social insects, which he used as a model for understanding the evolution of social behavior in animals and humans. His 1975 book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis argued that many aspects of animal and human behavior, including altruism, aggression, and social hierarchies, could be explained by evolutionary theory and the principles of natural selection. While controversial at the time, Wilson’s ideas helped to establish sociobiology as a major field of study and paved the way for the development of evolutionary psychology and behavioral ecology.

Beyond his scientific research, Wilson was a passionate advocate for conservation and biodiversity. In books like Biophilia (1984) and The Diversity of Life (1992), he argued that humans have an innate emotional connection to nature and a responsibility to protect the incredible variety of life on Earth. He warned of the accelerating rate of species extinction due to human activities and called for urgent action to preserve threatened ecosystems and habitats.

This essay provides an in-depth exploration of Wilson’s life, ideas, and legacy. It traces his intellectual journey from his early fascination with ants to his later role as a public intellectual and environmental activist. It examines his major scientific contributions, including his theories of island biogeography, sociobiology, and biophilia, and assesses their impact on contemporary biology and conservation. Additionally, it considers Wilson’s efforts to bridge the divide between science and the humanities and to promote a holistic, interdisciplinary approach to understanding the natural world. Finally, it reflects on Wilson’s enduring influence and the challenges and opportunities facing his vision of a sustainable, biodiverse future.

Main Ideas and Key Themes:

Wilson’s research on social insects, especially ants, provided a foundation for his later work on sociobiology and the evolution of social behavior. He saw insect colonies as complex adaptive systems that could shed light on the origins of cooperation, communication, and division of labor in nature.

In Sociobiology, Wilson argued that many social behaviors in animals and humans, from parental care to warfare, could be explained by the principles of natural selection and the maximization of genetic fitness. While acknowledging the role of culture and learning, he emphasized the evolutionary roots of human nature and the continuity between animal and human societies.

Wilson’s concept of biophilia suggests that humans have an innate affinity for nature and a psychological need to connect with other living things. He argued that this emotional bond with nature is the product of our evolutionary history and is essential for our mental and physical well-being.

As a conservationist, Wilson stressed the practical and ethical importance of preserving biodiversity. He warned that human activities, from habitat destruction to climate change, were causing a mass extinction of species and irreparable harm to the biosphere. He called for a global effort to protect endangered species, set aside large tracts of wilderness, and transition to a sustainable, ecologically-minded society.

Wilson sought to unite the sciences and humanities in the quest to understand the human condition and our place in nature. He believed that fields like biology, psychology, anthropology, and sociology could provide complementary insights into the complex interplay of genes, culture, and environment that shapes human behavior and social institutions.

Throughout his career, Wilson emphasized the role of scientific curiosity, creativity, and collaboration in pushing the boundaries of knowledge. He saw science not just as a method for understanding the world but as a source of wonder, beauty, and moral inspiration.

Sociobiology and Its Reception:

The publication of Sociobiology in 1975 marked a turning point in Wilson’s career and sparked a fierce debate about the role of biology in shaping human behavior and society. In the book, Wilson argued that many aspects of social behavior in animals, from cooperation and altruism to aggression and dominance hierarchies, could be explained by the principles of natural selection and the maximization of genetic fitness.

Wilson proposed that social behaviors evolve because they increase the reproductive success of individuals and their close relatives, even if they may be costly or risky in the short term. For example, he suggested that altruistic acts like sharing food or defending the group against predators could be favored by natural selection if they helped to ensure the survival and reproduction of one’s kin, who share many of the same genes.

While Wilson’s analysis focused primarily on non-human animals, he also extended his ideas to human behavior and society. He argued that traits like parental care, sexual jealousy, and xenophobia had deep evolutionary roots and could be understood as adaptations to the social and ecological challenges faced by our ancestors. He suggested that the principles of sociobiology could shed light on the origins of human culture, morality, and social institutions, from the family to the nation-state.

Wilson’s ideas were met with both enthusiasm and fierce criticism from other scientists, philosophers, and social activists. Some praised sociobiology as a bold and rigorous attempt to integrate the biological and social sciences and to provide a unified theory of behavior. They saw it as a natural extension of Darwin’s theory of evolution and a powerful tool for understanding the complex web of interactions between genes, organisms, and environments.

However, many critics accused Wilson of genetic determinism, reductionism, and the justification of existing social inequalities. They argued that sociobiology downplayed the role of culture, learning, and individual agency in shaping human behavior and ignored the complex historical and political factors that influence social relations. Some charged that Wilson’s ideas could be used to justify racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination, by suggesting that social hierarchies and differences were the inevitable product of biology rather than the result of power and oppression.

The controversy surrounding sociobiology reached a boiling point in the late 1970s, with protests and personal attacks against Wilson at academic conferences and in the media. Some activists even dumped a pitcher of water on Wilson’s head during a scientific meeting, accusing him of being a fascist and a promoter of “racist pseudoscience.”

Despite the backlash, Wilson stood by his ideas and continued to develop and refine his arguments in subsequent books and articles. He emphasized that sociobiology was not a prescription for human behavior or social policy, but a scientific framework for understanding the complex interplay of genes, environment, and culture in shaping social systems. He also acknowledged the limitations of his theory and the need for further research and dialogue across disciplinary boundaries.

Over time, many of the core ideas of sociobiology were absorbed into mainstream biology and psychology, even as the term itself fell out of favor. Fields like evolutionary psychology, behavioral ecology, and gene-culture coevolution built on Wilson’s insights and methods, while also addressing some of the criticisms and limitations of his original formulation. Today, the study of the biological basis of social behavior is a thriving and diverse area of research, with applications ranging from animal conservation to human health and well-being.

Looking back, the sociobiology debate can be seen as a watershed moment in the history of science and a reflection of the deep tensions and uncertainties surrounding the role of biology in human affairs. While Wilson’s ideas were controversial and sometimes overstated, they helped to spark a productive dialogue about the complex interplay of nature and nurture, genes and culture, in shaping who we are and how we live together. As we continue to grapple with these questions in the 21st century, Wilson’s legacy reminds us of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, critical thinking, and the responsible use of scientific knowledge in the service of humanity and the planet.

Biophilia and Biodiversity Conservation:

One of the key themes that runs throughout Wilson’s work is the idea of biophilia, or the innate human affinity for nature and living things. First introduced in his 1984 book of the same name, the biophilia hypothesis suggests that humans have a deep-seated psychological need to connect with the natural world and that this connection is essential for our mental and physical well-being.

Wilson argued that biophilia is the product of our evolutionary history and the result of the close relationship between humans and nature over millions of years. For most of our existence as a species, we have depended on the diversity and richness of the natural environment for our survival and flourishing. From the food we eat to the air we breathe, from the materials we use to the landscapes we inhabit, nature has shaped every aspect of our lives and left a deep imprint on our minds and bodies.

According to Wilson, this evolutionary bond with nature is not just a matter of practical necessity but also a source of emotional and spiritual fulfillment. He suggested that humans have a natural curiosity and fascination with other living things, from the smallest microbe to the largest mammal, and that this curiosity is the basis for much of our scientific knowledge and artistic inspiration. He also argued that exposure to nature, whether through outdoor recreation, gardening, or simply looking at a beautiful landscape, can reduce stress, improve mood, and promote feelings of well-being and connectedness.

However, Wilson warned that the modern world is increasingly disconnected from nature, with dire consequences for both human health and the environment. He noted that the rapid pace of urbanization, industrialization, and technological change has left many people feeling alienated and cut off from the natural world. At the same time, human activities like deforestation, pollution, and climate change are causing unprecedented damage to ecosystems and driving countless species to extinction.

In response to this crisis, Wilson became a passionate advocate for biodiversity conservation and the protection of endangered species and habitats. In books like The Diversity of Life and Half-Earth, he argued that the incredible variety of life on Earth is not only a scientific marvel but also a vital resource for human survival and prosperity. He warned that the current rate of species loss, estimated at 100 to 1,000 times the natural background rate, is a threat to the stability and resilience of the biosphere and a moral tragedy of the highest order.

To address this crisis, Wilson called for a global effort to set aside large tracts of land and ocean as protected areas, with the ultimate goal of preserving half of the Earth’s surface for nature. He argued that this “Half-Earth” strategy was necessary to prevent the collapse of biodiversity and to ensure the long-term health and well-being of both humans and the planet. He also emphasized the importance of scientific research, public education, and international cooperation in achieving this goal, and he worked tirelessly to promote conservation efforts around the world.

Wilson’s ideas about biophilia and biodiversity have had a profound influence on the fields of ecology, conservation biology, and environmental ethics. His writings have inspired countless individuals to reconnect with nature and to take action to protect the planet’s threatened species and ecosystems. At the same time, his vision of a world in which humans and nature can thrive together has challenged us to rethink our relationship with the natural world and to imagine a more sustainable and equitable future.

As we face the daunting challenges of the 21st century, from climate change to the loss of biodiversity, Wilson’s legacy reminds us of the urgent need to embrace our connection with nature and to work towards a world in which all forms of life can flourish. Whether through individual actions like planting a garden or supporting conservation organizations, or through collective efforts like creating protected areas and transitioning to a green economy, each of us has a role to play in realizing Wilson’s vision of a biophilic future. As he wrote in Biophilia, “We must learn to love, admire, and join with life in all its endless forms if we are to extend our stay on this planet with dignity.”

Bridging Science and the Humanities:

Throughout his career, Wilson sought to bridge the gap between the natural sciences and the humanities, arguing that a more integrated and holistic approach to knowledge was necessary to address the complex challenges facing humanity and the planet. He believed that the traditional division between the “two cultures” of science and the humanities was artificial and counterproductive, and that a deeper understanding of the human condition required insights from both realms.

In books like Consilience and The Meaning of Human Existence, Wilson argued that the principles and methods of science, particularly evolutionary biology, could shed light on a wide range of human phenomena, from language and culture to ethics and religion. He suggested that fields like psychology, anthropology, and sociology could benefit from a more rigorous and empirical approach, grounded in the study of the biological and evolutionary basis of human behavior.

At the same time, Wilson emphasized that science alone could not provide a complete understanding of the human experience or a satisfactory guide for moral and social action. He acknowledged the importance of the humanities, including literature, art, and philosophy, in exploring the subjective and existential dimensions of human life and in shaping our values and aspirations. He also recognized the role of culture and history in shaping human societies and the need for a more contextualized and nuanced approach to social and political issues.

Wilson’s vision of consilience, or the unity of knowledge, called for a more interdisciplinary and collaborative approach to research and education. He argued that the most pressing problems facing humanity, from poverty and inequality to environmental degradation and climate change, required insights and solutions from multiple fields and perspectives. He also suggested that a more integrated understanding of the natural world could inspire a sense of wonder, humility, and responsibility towards the planet and its inhabitants.

One of the key areas in which Wilson sought to bridge science and the humanities was in the study of human nature and the origins of morality. In books like On Human Nature and The Social Conquest of Earth, he argued that the capacity for ethical behavior and social cooperation was a product of human evolution and the result of the interplay between genetic and cultural factors. He suggested that the principles of evolutionary biology, particularly the concepts of kin selection and group selection, could help to explain the origins of altruism, empathy, and moral sentiments in human societies.

However, Wilson also recognized the limitations of a purely biological approach to ethics and the need for a more nuanced and context-dependent understanding of moral reasoning. He acknowledged the role of culture, history, and individual experience in shaping moral beliefs and practices, and he emphasized the importance of dialogue and debate in resolving ethical dilemmas and promoting social progress. He also warned against the dangers of moral absolutism and the need for a more pragmatic and flexible approach to ethical decision-making.

Throughout his writings, Wilson sought to promote a sense of wonder and appreciation for the natural world and the incredible diversity of life on Earth. He argued that the study of biology, particularly the evolution and ecology of organisms, could provide a rich source of aesthetic and spiritual inspiration, as well as a foundation for a more sustainable and harmonious relationship with nature. He also suggested that the humanities, particularly literature and art, could help to cultivate a sense of empathy and connection with other living beings and to imagine alternative ways of living and being in the world.

In his later years, Wilson became increasingly concerned about the threat of climate change and the need for urgent action to address the environmental crisis. He argued that the challenge of sustainability required a fundamental shift in human values and priorities, as well as a more integrated and holistic approach to science, technology, and policy. He called for a new era of “Enlightenment environmentalism,” grounded in reason, evidence, and a commitment to social justice and the well-being of all species.

Wilson’s legacy as a bridger of science and the humanities continues to inspire scholars, activists, and citizens around the world. His vision of consilience, his passion for the natural world, and his commitment to the responsible use of knowledge for the betterment of humanity and the planet remain as relevant and urgent today as ever. As we face the daunting challenges of the 21st century, Wilson’s example reminds us of the power of curiosity, creativity, and collaboration to transform our understanding of ourselves and our place in the universe.

Legacy and Influence:

Edward O. Wilson’s impact on science, conservation, and public discourse can hardly be overstated. His groundbreaking research on social insects, his bold theorizing about the evolutionary basis of social behavior, and his passionate advocacy for biodiversity and environmental protection have left an indelible mark on the intellectual and cultural landscape of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

In the field of biology, Wilson’s work on island biogeography, sociobiology, and the theory of kin selection helped to transform our understanding of the complex web of interactions between genes, organisms, and environments. His research on the behavior and ecology of ants and other social insects provided a model for studying the evolution of cooperation, communication, and division of labor in nature, and his insights continue to inspire new generations of scientists and students.

Beyond his scientific contributions, Wilson’s writings and public engagement have had a profound influence on the environmental movement and the wider culture. His books, including Sociobiology, Biophilia, and The Diversity of Life, have reached millions of readers and helped to raise awareness about the importance of conservation and the value of biodiversity. His advocacy for the protection of endangered species and habitats, particularly through the Half-Earth Project, has galvanized efforts to set aside large tracts of land and ocean for nature and inspired a new generation of conservation leaders.

Wilson’s vision of consilience, or the unity of knowledge, has also had a lasting impact on the way we think about the relationship between science and the humanities. His call for a more integrated and interdisciplinary approach to research and education has influenced the development of fields like cognitive science, environmental studies, and the digital humanities, and his ideas continue to shape debates about the role of science in society and the future of higher education.

However, Wilson’s legacy is not without controversy or criticism. His sociobiological theories, particularly his extension of evolutionary principles to human behavior and society, have been the subject of intense debate and scrutiny, with some accusing him of genetic determinism, reductionism, and the justification of social inequalities. While Wilson himself rejected these charges and emphasized the complex interplay of biological and cultural factors in shaping human nature, the sociobiology debate remains a cautionary tale about the potential misuse of scientific ideas and the need for responsible and nuanced communication of research findings.

Moreover, some critics have argued that Wilson’s focus on individual organisms and genetic explanations of behavior has overlooked the importance of ecological and systemic factors in shaping the natural world. They suggest that a more holistic and dynamic understanding of nature, one that recognizes the complex interactions between species and their environments, is necessary to address the pressing challenges of the Anthropocene, from climate change to the loss of biodiversity.

Despite these criticisms, Wilson’s influence and legacy continue to grow, both within the scientific community and beyond. His ideas have inspired countless researchers, conservationists, and activists to pursue a deeper understanding of the natural world and to work towards a more sustainable and equitable future. His vision of a world in which humans and nature can thrive together, grounded in a sense of wonder, curiosity, and responsibility, remains a powerful and compelling call to action.

As we face the daunting challenges of the 21st century, Wilson’s legacy reminds us of the urgency and importance of bridging the divide between science and society, between knowledge and values, and between the human and the natural world. His example of intellectual courage, creativity, and compassion serves as a model for a new generation of scientists, scholars, and citizens, who must work together to address the complex and interconnected problems of our time.

In the end, perhaps Wilson’s greatest contribution was his unwavering belief in the power of science and reason to illuminate the mysteries of the universe and to guide us towards a better future. As he wrote in Consilience, “We are the offspring of history, and must establish our own paths in this most diverse and interesting of conceivable universes – one indifferent to our suffering, and therefore offering us maximum freedom to thrive, or to fail, in our own chosen way.”

As we continue to grapple with the profound questions of our existence and our place in the world, Wilson’s legacy will continue to inspire and challenge us to embrace the beauty and complexity of life in all its forms, and to work towards a future in which all species can flourish and thrive.

References:

Wilson, E. O. (1975). Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Harvard University Press.

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Harvard University Press.

Wilson, E. O. (1992). The Diversity of Life. Harvard University Press.

Wilson, E. O. (1998). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. Knopf.

Wilson, E. O. (2012). The Social Conquest of Earth. Liveright.

Wilson, E. O. (2014). The Meaning of Human Existence. Liveright.

Wilson, E. O. (2016). Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. Liveright.

Novacek, M. J. (2001). The Biodiversity Crisis: Losing What Counts. The New Press.

Pinker, S. (2002). The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Viking.

Segerstrale, U. (2000). Defenders of the Truth: The Battle for Science in the Sociobiology Debate and Beyond. Oxford University Press.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

The Symbolism of the Bollingen Stone

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

The Symbolism of Color in Dreams

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jung to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

The Origins and History of Consciousness

Jung’s Empirical Phenomenological Method

The Future of Jungian Thought

Jungian Analysts

0 Comments