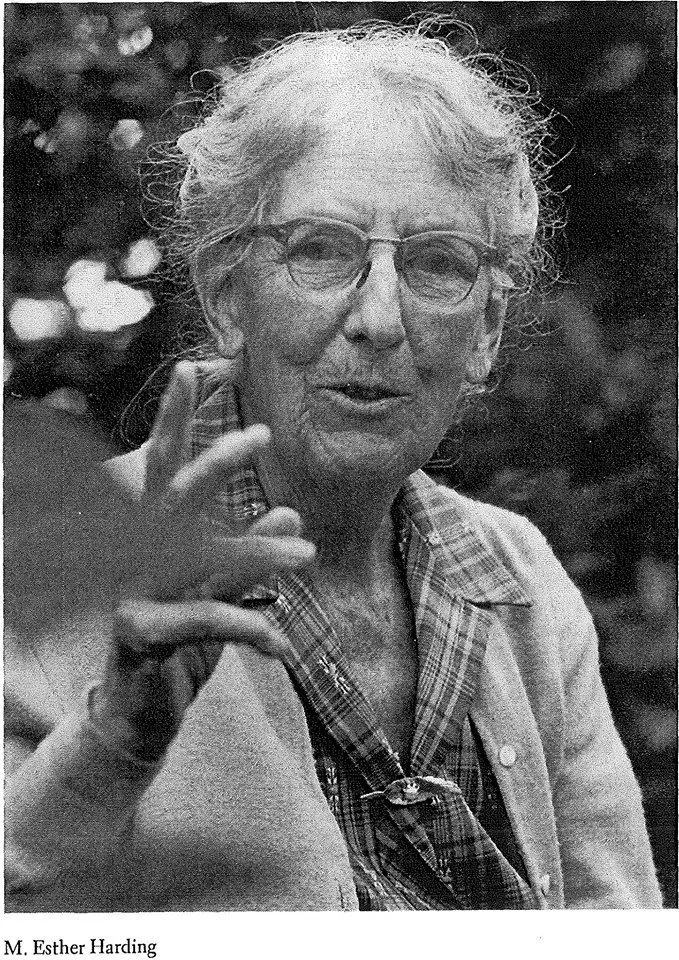

Who was Esther Harding?

“The recovery of the feminine, she suggests, is essential not only for women’s psychological and spiritual thriving but also for the healing of the world.”

Esther Harding (1888-1971) was a pioneering American Jungian analyst, author, and feminist known for her groundbreaking contributions to the understanding of feminine psychology and spirituality. As one of the first generation of Jungian thinkers, Harding played a crucial role in introducing Jung’s ideas to the English-speaking world and expanding their application to the lives of women.

Over her prolific career, Harding developed a distinctive approach to Jungian psychology that emphasized the centrality of the feminine principle and the importance of women’s psychological development. Drawing upon mythological, anthropological, and clinical material, she articulated a vision of feminine individuation that challenged prevailing patriarchal assumptions and affirmed the intrinsic value of women’s experience.

This essay provides an in-depth exploration of Harding’s thought and its significance for the fields of depth psychology, gender studies, and spirituality. It elucidates her key ideas regarding the nature of the feminine psyche, the archetypal patterns of women’s development, and the role of feminine spirituality in personal and cultural transformation. Additionally, it examines her pioneering work on the psychological interpretation of mythology and fairytales and her innovative use of Jungian concepts such as the anima/animus and the Self. Finally, it offers a retrospective on Harding’s scholarly legacy, assessing her enduring contributions to Jungian thought and her relevance for contemporary debates in psychology and feminism.

Main Ideas and Key Themes:

Harding articulates a theory of feminine psychology based on the centrality of the “feminine principle,” which she associates with receptivity, relatedness, and the capacity for transformation. She argues that traditional Jungian theory, while valuable, is often biased towards masculine patterns of development and neglects the unique features of women’s psychological experience. Harding identifies distinctive archetypal patterns and stages in feminine individuation, such as the “maiden,” “mother,” “queen,” and “wise woman,” which she sees as universal features of women’s psychospiritual development. She emphasizes the importance of women’s relationships, both personal and archetypal, in the individuation process, challenging the masculine ideal of heroic autonomy. Harding highlights the psychological significance of women’s biological experiences, such as menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause, as occasions for deepening self-knowledge and spiritual awakening. She advocates for a revaluation of feminine qualities and attributes, both in the individual psyche and in culture at large, as essential for psychic wholeness and societal balance. Harding explores the role of the “feminine divine” in women’s psychology, drawing upon mythological figures such as Demeter, Persephone, and the Virgin Mary as archetypal expressions of feminine sacrality. She argues for the importance of women’s spirituality as a path of direct experience of the numinous, one which has often been marginalized or suppressed by patriarchal religious traditions.

The Way of All Women:

The heart of Harding’s scholarly project is her elucidation of the distinctive features and developmental patterns of feminine psychology. Across a series of influential books — including The Way of All Women (1933), Women’s Mysteries (1935), and Psychic Energy (1947) — she articulates a comprehensive theory of women’s psychospiritual development and its archetypal underpinnings.

For Harding, the central dynamic of feminine psychology is the interplay between what she calls the “feminine principle” and the “masculine principle.” The feminine principle, which she associates with the archetype of the Great Mother, is characterized by qualities of receptivity, relatedness, embodiment, and the capacity for inner-directed transformation. In contrast, the masculine principle, associated with the archetype of the Great Father, is characterized by qualities of activity, autonomy, abstraction, and outer-directed striving.

Harding argues that while both principles are present in all individuals, women’s psychological development is fundamentally shaped by the feminine principle. She suggests that women’s sense of self is typically more fluid, relational, and contextual than men’s, and that women’s path of individuation often involves a deepening into the feminine qualities of receptivity, nurturance, and embodied wisdom.

At the same time, Harding emphasizes that feminine development is not a matter of simply identifying with traditional feminine roles or stereotypes. Rather, it involves a complex negotiation between archetypal energies and personal experience, a dialectic of inner and outer worlds. Drawing upon mythological motifs and clinical case studies, she traces the archetypal stages of women’s individuation from the “maiden” to the “mother” to the “queen” to the “wise woman,” each with its own characteristic tasks, challenges, and opportunities for growth.

Central to this process, for Harding, is the cultivation of what she calls “feminine Eros” — the relational, receptive, and transformative power of love. She argues that women’s psychological and spiritual development is intimately bound up with the capacity for deep, authentic connection — with oneself, with others, and with the larger mysteries of life. This feminine Eros, she suggests, is not merely personal but also transpersonal, a gateway to the archetypal and numinous dimensions of the psyche.

Harding is careful to note that this valorization of the feminine does not imply a denigration of the masculine. On the contrary, she sees both principles as essential for psychic wholeness and emphasizes the importance of their integration and balance within the individual. However, she argues that in a patriarchal society, the feminine principle has been systematically devalued and repressed, both in culture and in the psyche. As such, the task of feminine individuation necessarily involves a reclamation and revaluation of the feminine, a healing of the “wounded feminine” that has been exiled to the margins of collective life.

This reclamation, for Harding, is not just a personal matter but also a cultural and even planetary imperative. She argues that the one-sided development of the masculine principle in Western civilization has led to a dangerous imbalance, evident in the domination of nature, the oppression of women, and the proliferation of violence and war. The recovery of the feminine, she suggests, is essential not only for women’s psychological and spiritual thriving but also for the healing of the world.

Women’s Mysteries and the Feminine Divine:

A central theme in Harding’s work is the exploration of women’s unique spiritual experiences and their relationship to archetypal patterns of feminine divinity. In books like Women’s Mysteries and The Way of the Goddess, she examines the psychological significance of women’s biological and embodied experiences, such as menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause, and their connections to ancient mythological motifs.

For Harding, these experiences are not merely biological events but also spiritual initiations, gateways to the mysteries of the feminine divine. She argues that in ancient cultures, women’s bodily cycles were often seen as sacred occasions, linked to the rhythms of the earth and the cycles of death and rebirth. Women’s capacity to bleed without dying, to give birth, and to undergo the transformations of menopause were viewed as signs of their inherent spiritual power and wisdom.

In contrast, Harding suggests, patriarchal cultures have tended to denigrate or demonize women’s embodied experiences, seeing them as sources of pollution or irrationality. This devaluation, she argues, has cut women off from a vital source of spiritual nourishment and self-knowledge, alienating them from the deep feminine wisdom of the body.

Harding seeks to recover this wisdom by exploring the mythological and archetypal dimensions of women’s experiences. Drawing upon figures such as the Greek goddesses Demeter and Persephone, the Egyptian goddess Isis, and the Virgin Mary, she articulates a vision of the sacred feminine that affirms the spiritual significance of women’s embodiment and relationality.

For example, Harding interprets the myth of Demeter and Persephone as a powerful expression of the mother-daughter bond and its centrality in women’s psychological development. She suggests that the story of Persephone’s abduction and return reflects the archetypal pattern of feminine initiation, in which the young woman must descend into the underworld of the unconscious in order to emerge transformed and empowered.

Similarly, Harding sees the figure of the Virgin Mary as a profound symbol of feminine sacrality and the importance of women’s spiritual autonomy. She argues that Mary represents the feminine capacity for direct relationship with the divine, unmediated by masculine authority or control. By identifying with Mary, women can reclaim their own spiritual sovereignty and give birth to the divine within themselves.

Harding emphasizes that these mythological and archetypal patterns are not merely historical curiosities but living realities that continue to shape women’s experiences in the present day. By engaging with these motifs, she suggests, women can tap into the deep feminine wisdom of the psyche and connect with the transformative power of the feminine divine.

At the same time, Harding is careful to distinguish her approach from a simplistic goddess worship or a romanticization of ancient matriarchies. She recognizes the complexity and ambivalence of the archetypal feminine, which encompasses both light and dark, creation and destruction, nurture and ferocity. The task, she suggests, is not to idealize the feminine but to recognize its full spectrum and to integrate its many faces into a balanced and holistic psychospiritual vision.

Throughout her work, Harding emphasizes the importance of women’s direct experience of the sacred as the foundation of feminine spirituality. Rather than relying on external authorities or dogmas, she encourages women to trust their own inner knowing and to cultivate a personal relationship with the numinous. This may take many forms, from solitary contemplation to participation in women’s circles and ritual groups.

Ultimately, for Harding, the recovery of feminine spirituality is essential not only for women’s individual thriving but also for the transformation of culture and society. By reclaiming the sacred feminine, women can help to heal the wounds of patriarchy and to create a more balanced, compassionate, and life-affirming world.

The Psychological Interpretation of Mythology:

Another significant contribution of Harding’s work is her innovative use of Jungian concepts to interpret mythological and fairytale motifs. Like Jung, Harding sees these stories as profound expressions of archetypal patterns and psychospiritual truths. However, she brings a distinctly feminist perspective to her analysis, highlighting the ways in which these motifs illuminate the unique features of women’s psychological experience.

In books like Journey into Self and The I and the Not-I, Harding applies Jungian concepts such as the archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the process of individuation to a wide range of mythological and literary texts. She is particularly interested in stories that feature heroic female protagonists, such as the Greek myths of Psyche and Ariadne, the Celtic tales of the Arthurian women, and the fairytales of the Brothers Grimm.

For Harding, these stories are not simply entertaining fictions but powerful psychic maps that chart the terrain of women’s inner lives. By identifying the archetypal patterns and themes in these narratives, she suggests, women can gain insight into their own psychological struggles and potentials, and find guidance for their personal journeys of transformation.

For example, in her analysis of the Psyche myth, Harding interprets the heroine’s trials and adventures as a symbolic representation of the feminine individuation process. She suggests that Psyche’s journey reflects the archetypal pattern of feminine descent and rebirth, in which the heroine must confront the dark, unconscious aspects of her own psyche in order to emerge transformed and empowered.

Similarly, in her discussion of the Grimms’ fairytale “Allerleirauh,” Harding sees the story of the young woman who flees her incestuous father as a profound expression of the feminine quest for autonomy and self-definition. She suggests that the heroine’s disguise as a lowly kitchen maid reflects the ways in which women’s true selves are often hidden or devalued in patriarchal culture, and that her eventual recognition by the prince represents the validation of feminine identity and worth.

Harding emphasizes that these mythological and fairytale motifs are not simply relics of the past but continue to resonate with women’s experiences in the present day. By engaging with these stories, she suggests, women can tap into the collective wisdom of the feminine psyche and find inspiration and guidance for their own lives.

At the same time, Harding is careful to acknowledge the limitations and biases of traditional mythological and literary representations of women. She recognizes that many of these stories were written by men and reflect patriarchal assumptions and values. As such, she emphasizes the importance of a critical, feminist reinterpretation of these texts, one which uncovers their submerged feminine meanings and reclaims their liberatory potential.

Harding also stresses the importance of women creating their own myths and stories, ones which reflect the fullness and complexity of feminine experience. She suggests that by giving voice to their own narratives, women can help to reshape the collective imagination and create new templates for feminine identity and empowerment.

Ultimately, for Harding, the psychological interpretation of mythology is not simply an academic exercise but a vital tool for women’s self-understanding and transformation. By excavating the archetypal dimensions of these ancient tales, she suggests, women can reconnect with the deep feminine wisdom of the psyche and find new ways to embody their own unique paths of individuation.

Harding’s Legacy and Relevance:

Esther Harding’s pioneering work in feminine psychology and spirituality had a profound impact on the development of Jungian thought and the wider fields of depth psychology and women’s studies. Her articulation of a distinctly feminine path of individuation, her exploration of women’s archetypal experiences and patterns of development, and her emphasis on the psychological significance of women’s embodiment and relationality all helped to expand and enrich the Jungian tradition.

Harding’s influence can be seen in the work of subsequent generations of Jungian analysts and scholars, many of whom have built upon her insights and applied them to new areas of inquiry. For example, analysts such as Marion Woodman and Clarissa Pinkola Estés have further developed Harding’s ideas about the importance of the body and the archetypal feminine in women’s psychological and spiritual development. Similarly, scholars such as Christine Downing and Naomi Goldenberg have drawn upon Harding’s work to articulate feminist approaches to mythology, religion, and spirituality.

At the same time, Harding’s work has also been subject to critique and revision by later generations of feminists and depth psychologists. Some have argued that her emphasis on archetypal patterns and universal experiences of femininity risks essentializing or romanticizing women’s lives, and fails to account for the diversity and complexity of women’s identities and experiences. Others have suggested that her valorization of traditional feminine roles and attributes, such as motherhood and nurturance, may reinforce limiting stereotypes and fail to challenge the underlying structures of patriarchal oppression.

Despite these critiques, however, Harding’s work remains a vital resource for contemporary scholars and practitioners in the fields of psychology, spirituality, and feminism. Her emphasis on the centrality of the feminine principle, her exploration of women’s archetypal experiences and patterns of development, and her vision of a spirituality grounded in women’s direct experience of the sacred all continue to inspire and inform new generations of thinkers and seekers.

In particular, Harding’s insights into the psychological and spiritual significance of women’s embodiment and relationality seem especially relevant in an age of increasing ecological crisis and social fragmentation. Her call for a revaluation of feminine qualities and attributes, both in the individual psyche and in culture at large, resonates with contemporary movements for gender equality, environmental sustainability, and social justice.

Moreover, Harding’s emphasis on the importance of mythology and storytelling as tools for psychological and spiritual growth seems particularly apt in a time of cultural upheaval and transformation. Her recognition of the power of narrative to shape individual and collective identities, and her insistence on the need for women to create their own liberatory myths and stories, offer valuable resources for the project of cultural healing and renewal.

Ultimately, Esther Harding’s legacy lies not only in her specific contributions to Jungian thought and feminist psychology but also in her larger vision of a world in which the feminine principle is fully valued and integrated. Her work challenges us to reclaim the deep feminine wisdom of the psyche, to honor the sacredness of women’s embodied and relational experiences, and to work towards a more balanced, compassionate, and life-affirming culture. As we navigate the challenges and opportunities of our own time, her insights and example continue to light the way.

Selected Bibliography:

The Way of All Women (1933)

Women’s Mysteries: Ancient and Modern (1935)

Psychic Energy: Its Source and Its Transformation (1947)

The I and the Not-I: A Study in the Development of Consciousness (1965)

The Parental Image: Its Injury and Reconstruction (1965)

The Value and Meaning of Depression (1970)

Woman’s Mysteries: Ancient and Modern (1971, revised edition)

The Way of the Goddess (1976, published posthumously)

Journey into Self (1956)

Life Timeline:

1888: Born in Shropshire, England

1912: Graduated from Newnham College, Cambridge with a degree in mathematics

1919: Moved to the United States and began working as a teacher and social worker

1922: Began analysis with Eleanor Bertine, a student of Jung, and became involved in the Jungian community in New York

1932: Met Jung for the first time when he visited the US; began a long correspondence and collaboration with him

1933: Published her first book, The Way of All Women, which established her as a leading voice in feminine psychology

1935: Published Women’s Mysteries, a groundbreaking study of the archetypal dimensions of women’s experiences

1941: Co-founded the Analytical Psychology Club of New York, which became a center for Jungian thought and practice in the US

1947: Published Psychic Energy, a major theoretical work on the nature and transformation of psychological energy

1948: Became a founding member and first secretary of the Jung Institute of New York

1950s-60s: Continued to publish influential works on feminine psychology, mythology, and spirituality, including The I and the Not-I (1965) and The Parental Image (1965)

1971: Published a revised and expanded edition of Women’s Mysteries, incorporating new insights and material

1971: Died in Monterey, California at the age of 83

Harding’s approach to the study of Jung’s work was marked by a deep respect for the transformative power of the psyche and a commitment to exploring the archetypal dimensions of human experience. Like Jung, she emphasized the importance of engaging with the symbolic and mythological layers of the unconscious, and she saw the task of individuation as a lifelong journey of self-discovery and spiritual growth.

At the same time, Harding brought a distinctly feminist perspective to her interpretation of Jungian ideas. She was attentive to the ways in which Jung’s theories often privileged masculine experience and imagery, and she worked to articulate a vision of psychological development that honored the unique qualities and challenges of the feminine psyche.

In her writings and lectures, Harding often drew upon her own experiences as a woman and a therapist to illustrate her ideas. She was known for her vivid and poetic style, as well as her ability to translate complex psychological concepts into accessible and engaging language. Her work was infused with a deep sense of the numinous and the sacred, and she saw the task of individuation as ultimately a spiritual one.

Harding was also notable for her emphasis on the embodied and relational dimensions of psychological experience. Unlike some Jungian thinkers who tended to focus on intrapsychic processes, Harding recognized the profound influence of the body and of interpersonal relationships on the shape of the psyche. Her writings often explored the ways in which women’s physical and emotional experiences, such as menstruation, childbirth, and the mother-daughter bond, could serve as gateways to deeper self-understanding and spiritual awakening.

Throughout her career, Harding worked to bridge the gap between Jungian psychology and other fields such as anthropology, mythology, and religious studies. She was deeply influenced by the work of scholars such as Erich Neumann and Karl Kerényi, and she saw the study of archetypal patterns across cultures as essential to the project of understanding the human psyche.

Harding’s approach to Jungian thought was not without its critics, however. Some have argued that her emphasis on universal feminine archetypes risks essentializing women’s experiences and ignoring the ways in which gender is shaped by culture and society. Others have suggested that her valorization of traditional feminine roles and attributes, such as motherhood and intuition, may reinforce limiting stereotypes and fail to challenge patriarchal norms.

Despite these critiques, Harding’s work remains an important touchstone for many contemporary Jungian thinkers and practitioners. Her insights into the nature of the feminine psyche, her attention to the embodied and relational dimensions of experience, and her vision of individuation as a spiritual journey continue to inspire and inform new generations of scholars and seekers.

As the field of Jungian psychology continues to evolve and expand, Harding’s legacy serves as a reminder of the enduring power and relevance of depth psychology for understanding the complexities of the human experience. Her work invites us to engage with the mythological and archetypal layers of the psyche, to honor the wisdom of the body and the feminine, and to approach the task of self-discovery with curiosity, compassion, and a sense of the sacred.

In a world that is increasingly marked by ecological crisis, social fragmentation, and a longing for meaning and connection, Harding’s vision of a psychology that is grounded in the living wisdom of the psyche feels more relevant than ever. Her call to reclaim the feminine principle, to cultivate a more embodied and relational way of being, and to work towards a more balanced and integrated world continues to resonate with the challenges and opportunities of our time.

As we navigate the uncertainties of the present and the possibilities of the future, Esther Harding’s life and work offer a powerful example of what it means to live a life in service of the soul. Her legacy inspires us to trust in the transformative power of the psyche, to embrace the fullness of our humanity, and to work towards a world in which the feminine and the masculine, the personal and the collective, the psychological and the spiritual, are all honored and integrated. In this way, her contributions continue to light the way forward, guiding us towards a more whole and authentic way of being in the world.

Publications of Esther Harding:

- The Way of All Women (1933)

- Description: This seminal work establishes Harding as a pioneer in feminine psychology, exploring the distinctive features and developmental stages of women’s psychospiritual growth.

- Women’s Mysteries: Ancient and Modern (1935)

- Description: Harding delves into the archetypal dimensions of women’s experiences, connecting women’s biological and psychological cycles with mythological motifs.

- Psychic Energy: Its Source and Its Transformation (1947)

- Description: Harding examines the nature and transformation of psychological energy, drawing upon Jungian concepts to explore psychic dynamics.

- The I and the Not-I: A Study in the Development of Consciousness (1965)

- Description: This work explores the development of consciousness, emphasizing the interplay between inner and outer worlds in psychological growth.

- The Parental Image: Its Injury and Reconstruction (1965)

- Description: Harding addresses the psychological impact of parental influences, focusing on the formation and transformation of the parental image in individuals.

- The Value and Meaning of Depression (1970)

- Description: Harding discusses depression from a Jungian perspective, exploring its psychic origins, meanings, and transformative potential.

- Woman’s Mysteries: Ancient and Modern (1971, revised edition)

- Description: A revised edition expanding on her earlier work, integrating new insights into women’s psychospiritual development and mythological interpretations.

- The Way of the Goddess (1976, published posthumously)

- Description: Posthumously published, this book explores the archetype of the goddess and its significance for women’s spirituality and personal transformation.

- Journey into Self (1956)

- Description: Harding provides a personal and theoretical exploration of individuation and self-discovery, drawing on Jungian principles and mythological narratives.

Further Reading List:

Books:

- “The Pregnant Virgin: A Process of Psychological Transformation” by Marion Woodman

- Explores feminine psychology and spirituality through the lens of Jungian analysis.

- “Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype” by Clarissa Pinkola Estés

- Offers interpretations of myths and fairy tales from a Jungian perspective, focusing on the wild woman archetype.

- “Goddesses in Everywoman: Thirteen Powerful Archetypes in Women’s Lives” by Jean Shinoda Bolen

- Examines archetypal patterns in women’s personalities and relationships, integrating psychology and mythology.

Web Resources:

- The Jung Page

- Provides articles and resources on Jungian psychology, including applications to gender studies and spirituality.

- Esther Harding: A Tribute

- Offers a comprehensive overview of Harding’s life and contributions to Jungian psychology and feminist thought.

Bibliography of Sources Used:

- Harding, Esther. The Way of All Women. 1933.

- Harding, Esther. Women’s Mysteries: Ancient and Modern. 1935.

- Harding, Esther. Psychic Energy: Its Source and Its Transformation. 1947.

- Harding, Esther. The I and the Not-I: A Study in the Development of Consciousness. 1965.

- Harding, Esther. The Parental Image: Its Injury and Reconstruction. 1965.

- Harding, Esther. The Value and Meaning of Depression. 1970.

- Harding, Esther. Woman’s Mysteries: Ancient and Modern. 1971, revised edition.

- Harding, Esther. The Way of the Goddess. 1976, published posthumously.

- Harding, Esther. Journey into Self. 1956.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

The Symbolism of the Bollingen Stone

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

The Symbolism of Color in Dreams

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jung to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

The Origins and History of Consciousness

Jung’s Empirical Phenomenological Method

The Future of Jungian Thought

Jungian Analysts

0 Comments