The Generational Cycles of Trauma: A Parts-Based Perspective

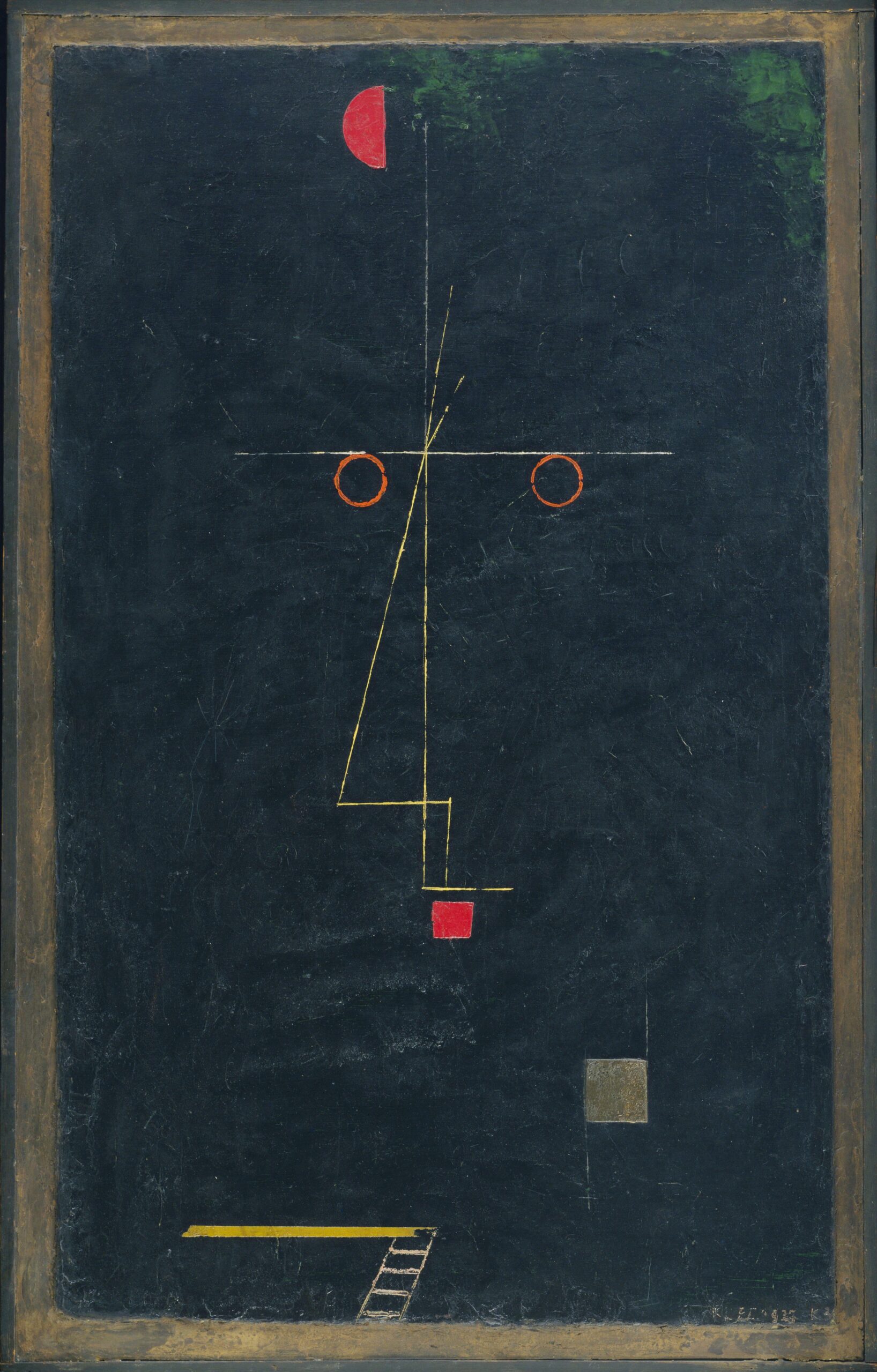

It has long been pointed out be different schools of therapy that the patterns that repeat in the individual psyche on a micro level also mirror the family system at a mezzo and the society at a macro level. Parts-based therapy, a post-jungian modality rooted in the recognition of distinct internalized aspects of the self, offers a valuable lens through which to understand these generational cycles.

Parts-based therapies represent an evolution of Jungian therapy, emerging in the 1980s and 1990s as Jungian analysts sought to fuse Jung’s analytical approach with experiential and somatic components. Modalities like Voice Dialogue and Process-Oriented Therapy moved away from endless intellectualization, instead emphasizing direct engagement with the embodied experience of different parts of the psyche.

More recently, Internal Family Systems (IFS), currently the fastest-growing and most popular parts-based approach, has integrated Jung’s map of the soul with cutting-edge research on somatic trauma and the experiential techniques of post-Gestalt therapy. Developed by Richard Schwartz, IFS drew upon Schwartz’s background in family therapy, recognizing the parallels between the compensatory mechanisms of the individual psyche and the patterns of guilt, shame, and triangulation often seen in family systems.

This essay will explore how the microcosmic insights of parts-based therapy can illuminate the macrocosmic dynamics of generational trauma and identity formation. By examining the ways in which different generations react to the perceived failures of their predecessors, we can see how collective identity mirrors the struggles of the individual psyche, with each new generation often overcorrecting for the excesses or deficits of the one before.

A key theme in this analysis is the role of trauma, which tends to manifest as either enmeshment with, avoidance of, or ambivalence towards different emotional states. These trauma responses operate on both individual and societal levels, shaping the unique challenges and blind spots of each generation.

While the broad strokes of this analysis paint generations in large categories, it’s important to recognize the fluidity of these boundaries – younger Gen Xers, for example, may share significant overlaps with older Millennials. Similarly, Gen Z overlaps with the emerging Gen Alpha. Millenials raised Gen Alpha primarily while Gen X raised Gen Z but not completely, etc. Individual variations also exist within each cohort.

“What is called the culture industry is no longer the sum of its individual branches but is rather the result of their fusion.” — Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947)

The Greatest Generation and the Primacy of the “Pusher”

The Greatest Generation, shaped by the hardships of the Great Depression and World War II, became profoundly over-identified with their inner “Pusher” part. Facing economic devastation and global conflict during their formative years, they developed a worldview that prioritized work, resilience, and self-sacrifice to an almost religious degree. The prevailing ethos was that rest was for the weak and that labor itself was a moral virtue. In order to survive, this generation had to suppress their “Vulnerable Child” part, learning to push aside their own emotional needs.

This emotional suppression had profound consequences for their children, the Baby Boomers. Raised by parents who expressed love primarily through providing material comfort and security, yet who often struggled to offer consistent emotional support, Boomers developed a complex relationship with achievement and recognition. Many absorbed the implicit message that success and status were the primary measures of worth, while also internalizing a deep discomfort with vulnerability and emotional expression.

As Erich Fromm observed, this kind of conditional love can lead to a pervasive sense of alienation and anxiety, as individuals learn to prioritize external validation over authentic self-expression. Boomers, caught between the conflicting demands of their Inner Critic and Wounded Child, often struggled to find a stable sense of self-worth.

Boomers, Gen X, and the Latchkey Kid

As parents themselves, Boomers often repeated this pattern, showering their Gen X children with the material privileges and opportunities they had lacked, yet struggling to offer the kind of consistent emotional attunement and validation that kids need to develop secure attachments. Gen X became known as the “latchkey generation,” often left to fend for themselves as both parents worked long hours.

Many Boomers, having not fully processed their own childhood emotional wounds, unconsciously perpetuated a cycle of conditional love and unspoken expectations. Gen X children were over-provided for materially but under-provided for emotionally, leading to a deep sense of disconnection and disillusionment. As explored in the article “Why Parents Treat Children Differently,” such inconsistent treatment can breed resentment and insecurity among siblings.

At the same time, a widespread “People-Pleaser” tendency emerged among Boomers as a coping mechanism for their unmet emotional needs. This manifested on a cultural level as a pervasive “go along to get along” attitude – a conflict-avoidance strategy that allowed deeper tensions and resentments to fester unaddressed. Personal discontent was often sublimated into political and generational conflicts rather than dealt with directly in relationships.

“Every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.” — Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940)

Gen X and the Rejection of Boomer Values

Generation X bore the brunt of this emotional ambivalence as they came of age in the 1980s and early ’90s. On one hand, they enjoyed unprecedented material comfort and opportunities, benefiting from their Boomer parents’ hard-won economic successes. On the other hand, they grew up with a gnawing sense of emptiness and disconnection, intuitively feeling that the superficial trappings of success could not fill the void of authentic emotional connection.

Moreover, Gen X found that the values that had been instilled in them – authenticity, creativity, social responsibility – were increasingly out of step with a mainstream culture that prioritized materialism, competition, and corporate conformity. The earnest ideals of the ’60s and ’70s had given way to the glossy veneer of ’80s consumerism, leaving Gen X feeling disillusioned and adrift.

This sense of alienation was compounded by the rapid technological and economic shifts of the early ’90s. With the rise of the Internet and digital media, many of the skills and interests that Gen X had cultivated – analog artisanship, DIY “zine” publishing, grunge punk, and activism through decentralized localized networking – were suddenly rendered passé by the invention of the internet. Gen Xers often felt like the last of the analog generations, caught flat-footed by the pace of digital change.

Irionically it would be these types of artisinal, local, and “scene” culture and commerce that would come to define the millenial emo and hipster movements. However it was the corporate driven algorithms of the internet culture that allowed these values to spread to ubuiquitey and ultimately co-opted by the larger cultural sphere.

As Marshall McLuhan famously observed, new media technologies profoundly shape not only the content of culture, but the very ways in which we perceive and engage with the world. For Gen X, the transition from an analog to a digital media landscape wasn’t just a matter of learning new skills, but of fundamentally rewiring their brains and relational patterns.

Even the cultural touchstones that had once given Gen X a sense of generational identity began to feel hollow and co-opted. The “alternative” music, fashion, and art that had once been markers of authenticity and rebellion were swiftly commodified into marketing trends, leached of their countercultural power. Watching their sacred cows become corporate cash cows, many Gen Xers retreated into irony and apathy.

This dynamic of countercultural rebellion followed by commodification and disillusionment is a recurrent theme in the work of the Situationists, particularly Guy Debord. For Debord, the spectacle of consumer capitalism works precisely by absorbing all forms of authentic dissent and desire into its own logic, rendering rebellion itself just another commodity.

“The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.” —Guy Debord, Situationist Philosopher

The Solutions That Weren’t

“Totalitarianism has discovered a means of dominating and terrorizing human beings from within.” — Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951)

Paradoxically, the very cultural tendencies that Gen X rebelled against – consumerism, atomization, spectacle – were in some ways exacerbated by the digital revolution that Millennials would later harness. The DIY ethos, localism, and anti-consumerist stance of Gen X counterculture prefigured many of the solutions needed to address the alienation and ecological destruction wrought by late capitalism.

However, Gen X was ill-prepared for the “Californian Ideology” that would emerge from the convergence of the counterculture with the nascent tech industry – a fusion of New Left and New Right ideas that promised personal liberation through technological progress, while obscuring the consolidation of corporate power. While Gen Xers were adept at culture jamming and building alternative institutions, they often lacked the technical savvy to compete in an increasingly digitized economy.

It was the Millennials who would fully adapt to and innovate within this new techno-economic landscape, for better and for worse. Having come of age alongside the Internet, Millennials intuitively grasped its potential for both resistance and recuperation, connection and commodification. The political energies that had once flowed through underground zines and pirate radio now found expression through social media and online activism.

However, in learning to navigate the affordances and algorithms of digital platforms, Millennials also became enmeshed in their hidden logics of surveillance and behavioral modification. The same tools that enabled new forms of self-expression and social movement building could also be wielded for data extraction and political manipulation. In the end, the “revolutionary” potential of digital technology largely proved to be a mirage, more often reinforcing rather than challenging existing power structures.

“Science and technology revolutionize our lives, but memory, tradition and myth frame our response.” —Arthur M. Schlesinger, American Historian

Millennials and the Rise of Digital Natives

Millennials came of age as “digital natives,” inherently grasping how to navigate the new technological and cultural landscapes. Less burdened by nostalgic attachments to the old ways of doing things, they intuitively understood the new rules of the game – the power of personal branding, the fluidity of identity, the importance of adaptability in the face of constant change.

In many ways, Millennials absorbed the lessons of Gen X’s disillusionment and turned them into a kind of pragmatic utopianism. Rather than retreat from the mainstream in pursuit of an unattainable authenticity, Millennials learned to work within the system, using the tools of digital connectivity and self-curation to create new forms of meaning and community.

Importantly, Millennials were able to participate more actively in shaping the cultural narrative, defining the aesthetic and values of the digital age in a way that Gen X had been denied. While Gen X signifiers like grunge, Daria, and Clarissa Explains It All have largely faded from the cultural consciousness, Millennial touchstones continue to be celebrated and rebooted.

However, just as Gen X watched their cultural rebellion turn into a corporate farce, so too did Millennials eventually see their most cherished aesthetics and values co-opted by the mainstream. The artisanal, sustainable, community-oriented ethos that had once felt like a meaningful alternative to soulless consumerism became just another marketing trend, the stuff of cupcake shops and kombucha bars. Cultural critique became tongue-in-cheek commercial kitsch, rebellion just another latte flavor.

As the scholars Timotheus Vermeulen and Seth Abramson have argued, this dynamic reflects the broader cultural logic of “metamodernism” – a sensibility that oscillates between the earnest utopianism of modernism and the ironic detachment of postmodernism, never quite landing on either. For Millennials, caught between the siren song of authenticity and the inescapable reality of mediation, life itself became an endless exercise in “meta” self-reflexivity.

“The meta-modern generation understands that we can be both ironic and sincere in the same moment; that one does not necessarily diminish the other.” —Luke Turner, Metamodern Manifesto

Gen Z and the Crisis of Meaning

“The ‘communicative capitalism’ of the internet is precisely that: communication for its own sake, producing engagement that is endlessly valorized but rarely translated into material gains or real change.” — Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life (2014)

Generation Z, the children of Millennials, have grown up with a deep attunement to their own emotions but an often fraught relationship to the challenges and ambiguities of the wider world. As the first true digital natives, Gen Zers have never known a world without the Internet and social media. On one hand, this has allowed them to connect with like-minded others across all boundaries of space and time, fostering the development of radically inclusive, intersectional identities and communities. On the other hand, it has also bred a deep sense of alienation from their physical environments and local communities, a kind of virtual homesickness.

Moreover, Gen Z has come of age in a time of unprecedented ecological, economic, and political instability. They are the inheritors of a world ravaged by climate change, riven by inequality, and seemingly abandoned by the institutions meant to support them. This existential uncertainty, combined with the always-on pressures of social media, has unsurprisingly bred a pervasive sense of anxiety, depression, and even nihilism among many Gen Zers.

As the psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion observed, when the mind is overwhelmed by unprocessed sense impressions and emotions, it can fall into a state of “nameless dread” – a free-floating anxiety untethered from any specific object or cause. For many Gen Zers, raised in a world of informational overload and environmental collapse, this nameless dread has become a defining feature of their emotional landscape.

In response, some Gen Zers have sought refuge in ever-more granular and arcane forms of identity politics, using obscure labels and ideological shibboleths as a way to assert some sense of control over a chaotic world. Others have rejected labels altogether, embracing a kind of radical fluidity and individualism. But both responses, in their own ways, can sometimes represent a retreat from the messy work of building real-world solidarity and effecting systemic change.

As thinkers like Fredric Jameson and Gianni Vattimo have argued, the postmodern condition is characterized by a kind of “depthlessness” – a flattening of history, affect, and meaning into a ceaseless play of surfaces and simulations. In such a world, the very notion of a coherent self, rooted in a stable set of values and commitments, begins to feel increasingly untenable.

“The problem of the twenty-first century is the problem of the image-world… the various materialities in which the social world is inscribed.” —Baudrillard, Philosopher of Hyperreality

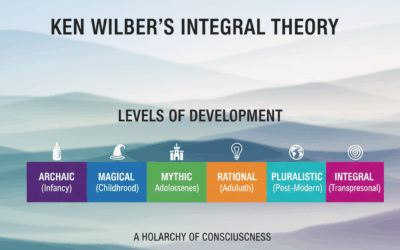

Towards a Post-Secular Spirituality of Integration From a parts-based therapy perspective, we can understand each generation’s signature struggles and blind spots as an overidentification with certain parts of the self and a disavowal of others. The Greatest Generation’s “Pusher” became the Boomers’ Inner Critic, which then split into Gen X’s disillusioned “Rebel” and Millennials’ idealistic “Dreamer.” Gen Z, in turn, has a highly developed “Vulnerable Child” but often a neglected “Competent Adult.”

The key to breaking these cycles of overreaction and counterreaction is not for any one generation to finally “get it right,” but for all of us to cultivate a greater capacity to hold and integrate all of our parts. We must learn to honor our “Pusher’s” drive and resilience while also making space for our “Vulnerable Child’s” need for rest and emotional connection. We must celebrate our “Rebel’s” quest for authenticity while also recognizing the value of our “Dreamer’s” aspirational visions. And we must nurture our “Competent Adult’s” ability to show up imperfectly to the hard work of building a world that works for everyone.

As the philosopher John Caputo suggests, this kind of integrative, “post-secular” spirituality is not about transcending the world, but about learning to love and affirm it in all its wounded, imperfect glory. It is about cultivating a radical openness to the other, a willingness to be transformed by the encounter with difference, a commitment to building solidarity across all lines of trauma and oppression.

Ultimately, the invitation of both parts-based therapy and generational healing is to move from a mindset of “either/or” to one of “both/and” – to resist the temptation to disavow any part of our individual or collective experience, but to instead embrace the wholeness of who we are. It is only by honoring all of our stories, struggles, and aspirations that we can hope to weave a future big enough for all of us. The work of integration is never done, but it is the only way forward.

Ultimately, the path forward lies not in the triumph of any one worldview or identity, but in our willingness to hold the tension of opposites, to embrace paradox, and to find meaning in the midst of complexity. By drawing on the deepest wisdom of our ancestral past and the most visionary aspirations of our collective future, we can begin to weave a new story – one that honors the full spectrum of human experience and potential.

In the end, the goal is not to arrive at some final, utopian resolution, but to find beauty and purpose in the eternal dance of integration and differentiation, stability and change, self and other. It is to recognize that, in the words of Walt Whitman, we “contain multitudes,” and that therein lies our strength, our resilience, and our hope for a more just and compassionate world.

“Do I contradict myself? Very well, then, I contradict myself; I am large — I contain multitudes.” —Walt Whitman, American Poet

Further Reading

Tensions of Culture and Psychotherapy

Lessons from the STAR*D Scandal

Incentivizing Evidence-Based Practice

A World of Broken Images: Healing the Modern Soul

The Corporatization of Healthcare

0 Comments