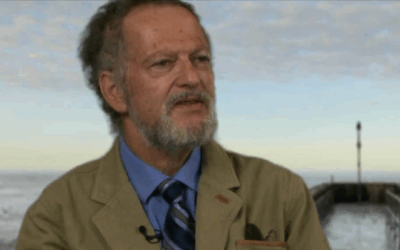

The Philosopher of the Animate Earth

For most of human history, the world was alive. Rivers spoke, mountains listened, and the wind carried messages. But in the modern West, we have silenced the world. We view nature as a collection of inert objects—resources to be used, not subjects to be met. David Abram (b. 1957) is the philosopher who is teaching us to listen again.

A cultural ecologist and geophilosopher, Abram is the author of the seminal book The Spell of the Sensuous. He merges the phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty with indigenous wisdom and sleight-of-hand magic. His work is essential for depth psychology because it relocates the “unconscious” from inside the human skull to the living landscape around us. He argues that we are not separate minds looking at the world, but bodies breathing with it.

Biography & Timeline: David Abram

Born in the suburbs of Long Island, Abram began his career as a professional sleight-of-hand magician. This trade took him to Indonesia, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, where he sought out indigenous shamans to trade magic tricks. What he found was that traditional magic was not about fooling people; it was about managing the relationship between the human village and the more-than-human world.

He returned to the U.S. to earn his Ph.D. in Philosophy at Stony Brook University. In 1996, he published The Spell of the Sensuous, which won the Lannan Literary Award and became a foundational text for the emerging field of Ecopsychology. He is the founder of the Alliance for Wild Ethics (AWE).

Key Milestones in the Life of David Abram

| Year | Event / Publication |

| 1957 | Born in Long Island, New York. |

| 1980s | Travels as an itinerant magician through Asia and the Americas. |

| 1993 | Receives Ph.D. from Stony Brook University. |

| 1996 | Publishes The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. |

| 2010 | Publishes Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. |

| Present | Directs the Alliance for Wild Ethics. |

Major Concepts: The Spell of Literacy

The More-Than-Human World

Abram coined the term “more-than-human world” to replace the word “nature” (which implies something separate from us). He argues that every aspect of the sensory world—birds, stones, weather—is expressive and animate. Perception is not a one-way street; when you touch a tree, the tree is also touching you.

The Alphabet and Disconnection

Why did we lose this animistic connection? Abram traces it to the invention of the phonetic alphabet. In oral cultures, language is tied to the breath and the land (e.g., a story about a mountain is told at the mountain). The alphabet severed language from the place. We began to speak to texts rather than to the terrain.

The Result: We became trapped in our own heads, viewing the world as a mute backdrop. Healing involves “re-animating” our language and senses.

The Conceptualization of Trauma: Ecological Grief

Abram’s work suggests that much of our modern anxiety and depression is actually ecological grief. We are animals who evolved to be in constant sensory reciprocity with a living environment. Living in concrete boxes, staring at screens, and breathing processed air is a form of sensory trauma.

Grounding as Therapy

Trauma disconnects us from the body and the present moment. Nature reconnects us.

Clinical Application: Therapy isn’t just about analyzing childhood; it’s about re-establishing a relationship with the ground. Practices like “forest bathing,” tracking, or simply sitting in silence with a landscape can bypass the cognitive defenses and soothe the nervous system. The earth is the ultimate “container” for our pain.

Legacy: The Ecology of Magic

David Abram is a bridge-builder. He connects the high philosophy of phenomenology with the dirt-under-the-fingernails reality of ecology. He reminds us that “psyche” originally meant “breath”—the air we share with the hawk and the oak tree.

His legacy is a call to a “wild ethics”—an ethics not based on abstract rules, but on a felt sense of kinship with the animate earth. As he writes, “We are only human in contact, and conviviality, with what is not human.”

Bibliography

- Abram, D. (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. Pantheon Books.

- Abram, D. (2010). Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. Pantheon Books.

0 Comments