As a practicing therapist, I find myself constantly grappling with the widening gulf between the realities of clinical work and the priorities of the academic and research establishment in psychology. We are living through a time of profound cultural and epistemological transition, and the assumptions that have long undergirded the mental health field are showing serious cracks. If psychotherapy is to remain relevant and vital in the coming decades, we will need to radically re-envision both the form and content of our work.

One of the central tensions I observe is the growing mismatch between the hyper-specialized, manualized approaches favored by much contemporary clinical research and the actual needs of patients as they present in my consulting room. The prevailing paradigm remains wedded to a reductionist view of the psyche, one that seeks to isolate and target discrete symptoms or syndromes while losing sight of the whole person. This is the legacy of the so-called “cognitive revolution” in psychology, which despite its promise of a more humanistic alternative to behaviorism, has in practice perpetuated many of the same mechanistic assumptions.

The result is a proliferation of three-and-four-letter acronyms masquerading as treatments: CBT, DBT, ACT, REBT and so on down the line. Each comes with its own set of worksheets and protocols and refereed journal articles attesting to its efficacy. But lost in this alphabet soup is any real reckoning with the lived experience of the suffering individual. The focus is on symptom reduction, not meaning-making; on skills acquisition, not self-discovery; on measurable outcomes, not existential grappling.

Meanwhile, the actual texture of my clinical work belies these neat categories. My patients come to me with a welter of contradictory impulses and fragmented self-concepts, their inner lives a palimpsest of family dynamics and cultural scripts and unarticulated yearnings. The presenting problem is often just the tip of the iceberg, a stand-in for deeper patterns of relating and being that defy any simplistic diagnosis. To meet them where they are, I must draw on a wide range of ideas and methods, from the psychodynamic to the humanistic to the transpersonal. No single theory or technique could possibly do justice to the mystery of a human soul in all its idiosyncratic unfolding.

This is why I believe the great schism in contemporary psychotherapy is not between this or that school of thought, but between those who recognize the irreducible complexity of the self and those who seek to tame it through ever-more-specialized compartmentalization. The latter mindset is a symptom of what the sociologist Max Weber called the “disenchantment of the world” – the progressive draining of wonder and subjective meaning from our experience in the face of rationalist reductionism.

In the realm of psychotherapy, this disenchantment manifests as a clinical culture that increasingly mimics the surface trappings of medical science – the white coats, the diagnostic checklists, the randomized controlled trials – while neglecting the art of healing. We forget that our role is not merely to manipulate behavior or cognition, but to midwife the soul’s journey towards wholeness. We forget that the self is not a problem to be solved, but a mystery to be lived.

Nowhere is this forgetting more evident than in the creeping medicalization of mental health treatment. With the rise of psychopharmacology and the insurance-driven push towards “evidence-based” practices, therapy is more and more seen as just another delivery system for standardized interventions. The result is a field that is simultaneously over-professionalized and under-professionalized – fixated on credentials and billing codes, yet often lacking in the kind of deep self-knowledge and existential grounding that true healing work requires.

As a corrective to this technicism, I believe we need to reconnect with the lineage of depth psychology stretching back to Freud and Jung – a tradition premised on the recognition that the psyche is fundamentally creative, symbolic, and transpersonal. This is not a matter of uncritically reviving century-old dogmas, but of learning to once again see therapy as an encounter with the numinous dimensions of experience. It means cultivating a sensibility that is phenomenological rather than abstractly intellectual, dialogical rather than diagnostic.

One particularly egregious example of this reductionist mindset is the rise of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) as the dominant paradigm for treating autism spectrum disorders. With its exclusive focus on observable behaviors and its reliance on rigid conditioning protocols, ABA epitomizes everything that is wrong with the medicalized approach to psychotherapy.

At its core, ABA is based on a fundamentally impoverished view of the self – one that reduces the rich inner life of the autistic person to a set of maladaptive behaviors to be eliminated through a regimen of rewards and punishments. The goal is not to foster autonomy or self-understanding, but to mold the individual into a more socially compliant and “normal” version of what others want them to be.

Each model and conception of psychotherapy as a self concept at its heart. Past models of therapy are sometimes overly complicated, philisophical, or intelectually abstract but most historic models of therapy had their place for some group of patients or some type of problem. Remember that all therapists engaging with the psyche honestly and non avoidantly are describing the same fundamental perrenial phenomenon but in own unique biases and around their own blindspots. We need to integrate, as a profession, multiple voiuces to avoid the inevitable blind spots of each. Recently cognitive and behavioral models like ABA have stripped everything out of the definitionof the self accept how clinicans can objectively measure a clients behavior. This idea of a psychotehrapy with no self, where we are only how a clinican interprets our behavior are horifying to me as a depth and somatic therapist.

In the process, the deep existential pain and alienation that often accompany the autistic experience are simply ignored or pathologized, rather than being seen as meaningful responses to a world that is often hostile and overwhelming to neurodivergent ways of being. The result is a kind of suffering that is all the more insidious for being invisible – patients are taught to scream on the inside instead of the outside. They are drive in to an inner world where the outter world does not have to listen to or look at the evidence of them suffereing.

This is the dark underbelly of the behaviorist worldview – the way it subtly dehumanizes those who fall outside the narrow bounds of what is considered productive or functional behavior. Instead of changing the world or advocating for the authentic self it changes the self to fit the conditions of modernity. By reducing the self to a bundle of conditioned responses, it denies the essential mystery and dignity of the human soul, in all its infinite variety and complexity.

As therapists, we must resist this kind of reductionism in all its forms, whether it takes the shape of ABA, CBT, or any other cognitive or beehavioral approach that promises to fix the psyche as if it were a malfunctioning machine. We must insist on the primacy of the self as a locus of meaning and value, rather than just a collection of symptoms to be managed or behaviors to be modified.

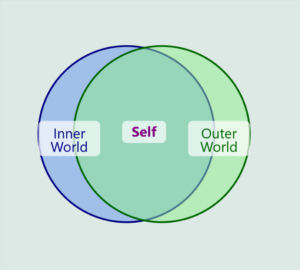

If we do want to keep the concept of self in therapy then we must continue to debate what the word means. But what exactly do we mean by “the self”? This is a question that has haunted Western philosophy and psychology for centuries, and there are no easy answers. At the very least, we can say that the self is not a static, monolithic entity, but rather a dynamic, multifaceted process that unfolds over time in interaction with the world.

Drawing on the insights of depth psychologists like Erich Neumann and Edward Edinger, we can see how this plays out in the tendency to become trapped in either the subjective realm of personal myths and fantasies, or the objective realm of literal facts and external achievements. In either case, we lose touch with the fullness of our being, which can only emerge in the dynamic interplay between these two poles.

Some become lost in the inner world of personal myths, fantasies, and emotions, losing touch with practical realities. Others identify solely with the literal facts and external achievements prized by our hyper-rational culture, severing connection with the symbolic and imaginative realms. In both cases, they forfeit the opportunity to embrace and integrate the full spectrum of human experience.

Yet as Neumann and Edinger point out, it is only in the dynamic interplay between these seemingly opposed poles – inner and outer, subjective and objective – that the true self can emerge. When we have the courage to hold the tension between them, resisting the temptation to collapse into either extreme, we access a deeper ground of wholeness. We discover, in Edinger’s words, “a consciousness that can contain the ego and the Self in a living paradox.”

Here the goal is not to eliminate or transcend the conflict between our inner experience and outer reality, but to develop the capacity to consciously bear it. In this crucible, where dreams and facts, feelings and reason, personal truth and collective necessity collide, the alchemy of individuation can unfold. We are challenged to weave a more encompassing worldview that honors both domains without becoming identified with either.

A truly integrative approach to psychotherapy must therefore begin by acknowledging this fundamental dialectic of human existence. It means cultivating the negative capability to dwell in the uncertainty and discomfort of this tension, rather than rushing to resolve it through reductionism or specialization. It means recognizing that the self is not to be found in either the inner or outer world alone, but in the crucible of their ongoing dialogue and confrontation.

A truly integrative approach to psychotherapy must therefore begin by acknowledging this fundamental dialectic of human existence. It means cultivating the negative capability to dwell in the uncertainty and discomfort of this tension, rather than rushing to resolve it through reductionism or specialization. It means recognizing that the self is not to be found in either the inner or outer world alone, but in the crucible of their ongoing dialogue and confrontation.

This has profound implications for both the theory and practice of the healing arts. It calls us to move beyond the limiting paradigms of symptom management and behavioral modification, and to engage the psyche in all its complexity, subtlety, and depth. It invites us to see therapy not as a technique to be mastered, but as a sacred space for the unfolding of soul – a crucible for the transformation of consciousness itself.

As we will explore, this vision demands much of us as therapists and as human beings. It requires us to confront our own shadows, to question our allegiances and assumptions, and to risk vulnerability and not-knowing in the service of something greater. But it also opens up new vistas of possibility and purpose, inviting us to participate more fully in the grand adventure of self-discovery and world-renewal. By learning to hold the tension of opposites within ourselves, we may just find the key to healing the rifts and contradictions that afflict our world.

In the therapeutic context, this means that we must be attentive to the ways in which our clients’ sense of self is shaped by the social, cultural, and historical contexts in which they are embedded. I have long argued that anthropology and philosophy are not things that can be removed from psychotherapy. We must recognize that the self is always in dialogue with the Other – that it emerges out of the matrix of relationships and experiences that make up a life, rather than existing in some kind of abstract, decontextualized vacuum.

At the same time, we must also honor the irreducible singularity of each individual self – the way it exceeds and transcends any simple categorization or diagnostic label. This is the paradox at the heart of the therapeutic encounter: that in order to truly see and understand the other, we must be willing to let go of our preconceptions and meet them in the raw, unfiltered reality of their being.

This is a daunting task, to be sure – one that requires a kind of radical openness and vulnerability on the part of the therapist. It means being willing to have our own sense of self challenged and transformed by the encounter with otherness, to let ourselves be drawn into the depths of another’s experience without losing our own grounding.

But it is precisely this kind of empathic attunement, this willingness to dance at the edge of the unknown, that distinguishes true healing from mere symptom management. For in the end, therapy is not about imposing our own agenda or expertise onto the client, but about creating a space in which they can discover and articulate their own deepest truths.

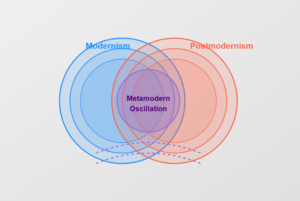

As we navigate the complexities of the current cultural moment, shaped by the breakdown of postmodernism and the emergence of a new “metamodern” sensibility, the work of therapy is undergoing a profound transformation. The metamodern age, as philosophers like Peter Sloterdijk have argued, is characterized by a constant oscillation between modernist faith and postmodern doubt, between the yearning for universal truth and the recognition of irreducible contingency.

In the political sphere, these oscillations manifest as a polarization between those who seek to reassert traditional values and boundaries, and those who embrace a more fluid, pluralistic vision of society. On one side, there is a nostalgia for the perceived stability and coherence of the past, a desire to resurrect clear lines of authority and identity. On the other side, there is a celebration of diversity, hybridity, and the transgression of fixed categories.

Yet both of these positions, in their extreme forms, can lead to a kind of brittleness and reactivity. The traditionalist stance can harden into a rigid fundamentalism that is unable to adapt to the complexities of the present. The progressive stance, meanwhile, can devolve into a relativistic “anything goes” attitude that lacks ethical and existential grounding.

In the cultural realm, the rapid cycling between irony and sincerity, deconstruction and reconstruction, can produce a kind of symbolic overload. The old myths and archetypes no longer hold sway, but a proliferation of new signs and images compete for our attention, often without any clear context or depth of meaning. This can result in a superficial, consumerist approach to culture, where styles and ideas are rapidly adopted and discarded in a perpetual search for novelty.

At the same time, the breakdown of cultural hierarchies and the democratization of media production have also led to a more participatory and diverse cultural landscape. Marginalized voices and perspectives have found new platforms for expression, challenging dominant narratives and representations. Yet this explosion of cultural production can also feel overwhelming, making it difficult to navigate and evaluate the flood of information and stimuli.

This oscillatory dynamic presents both challenges and opportunities for the therapeutic encounter. On one hand, the erosion of stable meaning structures and the crisis of hyperindividualism can leave patients feeling unmoored, alienated, and overwhelmed by the task of self-creation in a radically uncertain world. The ironic detachment and reflexivity of the postmodern mindset can make it difficult to access and articulate authentic emotional experience.

At the same time, the metamodern turn also opens up new possibilities for depth, connection, and transformation in the therapeutic process. By learning to sit with and even embrace the tension of opposites – between knowing and not-knowing, construction and revelation, irony and sincerity – therapist and patient can co-create a space of creative potential in which new meanings and forms of subjectivity can emerge.

In this sense, metamodern therapy is less about arriving at definitive answers or solutions than about cultivating the negative capability to dwell in uncertainty, paradox, and the unfolding mystery of being. It is a fundamentally poetic and improvisational endeavor, one that calls upon the full range of our human faculties – intellectual, emotional, intuitive, and somatic.

Modernism, with its emphasis on reason, progress, and universal truths, provided a sense of stability and direction but often at the cost of repressing or marginalizing other ways of knowing. It tended towards a kind of naive realism and epistemological certainty that failed to account for the constructed, contextual nature of knowledge.

Postmodernism arose as a necessary corrective, highlighting the ways in which all truth claims are shaped by language, power, and perspective. It embraced irony, relativism, and the deconstruction of grand narratives. While this brought a vital self-reflexivity and skepticism, taken to an extreme it could lead to a paralyzing nihilism, a sense that all meanings are equally arbitrary.

Metamodernism seeks a way forward that transcends this binary. It yearns for the depth and grounding of modernist meta-narratives while retaining the critical insights and destabilizing provocations of postmodernism. Metamodern sensibilities oscillate between poles of sincerity and irony, optimism and doubt, attempting to hold space for both rather than rejecting either.

In the therapeutic context, this means acknowledging the human need for coherent stories and a sense of existential direction while also holding these structures lightly, recognizing their ultimate contingency. It means embracing the transformative potential of authentic connection and communication even as we remain aware of the ways these are always mediated by culture, language, and power dynamics.

The postsecular turn, meanwhile, represents an attempt to recover the spiritual and transcendent dimensions of human experience without regressing to pre-modern religious dogmas. In an age where traditional religious structures and beliefs have lost credibility for many, there is nonetheless a persistent hunger for meaning, mystery, and experiences of the sacred.

Postsecularism posits that these yearnings need not be channeled into literalistic belief systems but can be cultivated through direct, embodied engagement with the numinous depths of the self and world. It sees the sacred not as something separate from or beyond the mundane, but as woven into the fabric of everyday life, accessible through altered modes of attention and presence.

For therapists, this suggests the importance of creating space for spiritual and existential questions, for grappling with matters of ultimate concern. It means honoring the client’s search for deeper purpose and connection, even if this takes unconventional or idiosyncratic forms. At the same time, it means approaching spirituality not as a set of received truths but as an ongoing process of discovery, an improvisational dance between immanence and transcendence.

Postsecularism, as articulated by thinkers like David Tacey, recognizes the persistence and resurgence of spiritual yearnings and sacred experiences in the contemporary world. Rather than seeing spirituality as a regressive retreat from reason, Tacey argues that a postsecular perspective integrates the rational and the mystical, acknowledging the validity of both. He suggests that in a postsecular age, “the sacred is no longer exclusively identified with religious or metaphysical ideologies, but is found and experienced in the here-and-now of everyday life, in nature, in relationships, and in the depths of the self.” He calls for someeething similar to what Jung taught, that we should not take religion litterally but should pay “religious attention” to life itself.

Jürgen Habermas, in particular, has argued that the secularization thesis – the idea that religion would gradually fade away as societies modernize – has proven to be overly simplistic. Instead, he observes a “post-secular” condition in which religious and secular worldviews coexist and interact in complex ways. In this context, Habermas calls for a “complementary learning process” in which both secular and religious citizens engage in a mutual dialogue, translating their respective insights into a shared language.

This requires, on the one hand, that secular society recognize the persistent vitality and relevance of religious traditions as sources of meaning, values, and motivation for many individuals. On the other hand, it demands that religious communities open themselves to the insights of secular reason and the norms of democratic discourse. The goal is not a bland consensus, but a vibrant and contestatory public sphere enriched by a diversity of voices that help us understand and ineffable transcendent perspective that lies beyond the cognitve and language based part of our brains.

Both postsecularism and metamodernism, I believe, offer important correctives to the avoidance and repression that enables evil to flourish in individuals and societies. By recognizing the spiritual and mythic dimensions of reality, they challenge the flattening reductionism of purely materialist worldviews. And by embracing the tension of opposites, they resist the temptation to collapse into either dogmatic certainty or nihilistic despair.

Core to this approach is the recognition that the self is not a fixed, unitary entity, but a fluid, multidimensional process that is always in dialogue with the social and symbolic fields in which it is embedded. The goal of therapy is thus not to excavate some hidden, “true” self, but to expand our capacity to flexibly enact different modalities of selfhood in response to the shifting demands of internal and external reality.

Postmodernism arose as a reaction against the naive realism and epistemological certainty of modernism. Where modernism emphasized reason, progress, and the pursuit of universal truths, postmodernism highlighted the ways in which all truth claims are inevitably shaped by the subjective factors of language, power, culture and individual perspective.

This led to a kind of pendulum swing from an over-emphasis on objectivity to a sometimes extreme relativism or subjectivism. Postmodernism’s focus on irony, the deconstruction of meta-narratives, and the arbitrariness of meaning tended to problematize notions of objective truth.

The metamodern sensibility, in contrast, seeks to transcend this binary, to find a way of honoring both objective and subjective realities. It recognizes the human need for coherent meanings and narratives, for some stable ground, while also acknowledging the contingency and contextuality of all knowledge.

Metamodernism thus involves a constant oscillation or balancing act between the objective and subjective poles. It strives for authenticity, depth and “felt meaning” while remaining skeptical of absolute truth claims. It embraces the transformative potential of resonant myths and meta-narratives, but holds them lightly, prepared to deconstruct or revise them as needed.

In the therapeutic context, this translates into an approach that values both the irreducible subjectivity of the patient’s lived experience and the objectifying knowledge provided by psychological theory and research. The therapist aims to empathically enter and validate the patient’s inner world, while also maintaining an orienting “third position” grounded in clinical understanding.

The goal is to co-create a transitional space in which the patient’s subjectivity can be held, explored and gradually transformed in dialogue with a more expansive view. This requires the therapist to gracefully oscillate between immersion and reflection, between attuning to the patient’s immediate experience and interpreting it through theoretical lenses.

Ultimately, metamodern therapy seeks to cultivate a kind of “negative capability,” a capacity to tolerate uncertainty and ambiguity, to dwell in the liminal space between objective and subjective realities without collapsing into either. It is in this fluid, dialectical space that new meanings, insights and forms of subjectivity can emerge.

This requires a kind of bifocal vision, an ability to oscillate between immersion in the patient’s lived experience and a more distanced, reflective stance grounded in theoretical understanding. The therapist must be able to empathically attune to the nuances of the patient’s emotional world, while also holding this experience within a larger interpretive frame informed by psychological knowledge and clinical wisdom.

At the heart of this process is the cultivation of what Carl Jung called the transcendent function – the capacity to hold the tension of opposites until a novel, integrative perspective emerges from the unconscious. In the metamodern context, this means learning to inhabit the gap between irony and sincerity, deconstruction and reconstruction, without collapsing into either pole prematurely.

At the heart of the self lies a fundamental duality – the division between the part of our psyche that deals with objective, empirical reality and the part that inhabits the subjective, personal sphere of emotions, fantasies, and meanings. This bifurcation is rooted in our evolutionary history, as the cognitive mechanisms for navigating the outer world developed alongside, but distinct from, the affective systems for regulating our inner experience.

Object relations theory offers a powerful framework for understanding this duality. It posits that our sense of self emerges out of the matrix of early relationships, as we internalize both the soothing and the frustrating aspects of our primary caregivers. These “objects” form the building blocks of our inner world, shaping our patterns of relating, our emotional responses, and our self-image.

The realm of internal objects is the domain of subjectivity – the space where we can engage in the imaginative play of art-making, immerse ourselves in the symbolic resonances of myth and metaphor, and grapple with the existential questions of meaning and purpose. It is the seat of our most authentic and spontaneous self-expression, unencumbered by the demands of external reality.

However, this inner world is not entirely divorced from the outer. The two realms are inextricably linked, influencing and interpenetrating each other in complex ways. Our emotional realities, shaped by our early experiences and unconscious fantasies, color our perceptions and reactions to the objective world. At the same time, our adaption to the challenges and opportunities of our environment continuously reshapes our internal landscape.

The key insight here is that while these two spheres are intimately connected, they operate according to different rules and logic. The external world is governed by the principles of cause-and-effect, the constraints of physical and social reality. The internal world, in contrast, is the realm of psychic reality, where memories, emotions, and symbols interact in fluid, non-linear ways.

Psychotherapy, then, must work at the interface of these two realities. It must help the individual to navigate the objective world more effectively, to reality-test their assumptions and perceptions, to develop practical skills and knowledge. But it must also plumb the depths of the inner world, to illuminate the unconscious patterns and motivations that drive our behavior, to enrich our self-understanding through the exploration of dreams, fantasies, and creative self-expression.

Here the insights of phenomenology and post-Cartesian philosophy become essential. Thinkers like Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Sloterdijk have argued persuasively that the self is not a disembodied mind, but a being-in-the-world whose very existence is fundamentally intertwined with the physical and social environments it inhabits. Authentic selfhood thus involves not an escape from the world, but a deeper, more intentional engagement with it.

This conjunction of the inner and outer sphere of human experience is evidenced by almost all the types of art and culture that we create and also is key to interpreting and understanding them. I have written in the past about this phenomenon in countless types of culture and media. Just to select on example that I have written about before, consider architecture.

We started our podcast reflecting on how architecture is a form of depth psychology in that it externalizes inborn archytypes. The more timeless forms of architecture tap into our latent potentialities, while the worst forms try to cut off from our inner experience to reinforce negative cultural heirarchies.

The work of Will Selman, an urban planner who has written on the intersection of depth psychology and urbanism, offers a compelling lens for re-envisioning the city as a space of psychological growth and wholeness. Drawing on the Jungian concept of temenos, the sacred precinct, Selman argues that we need to approach the entire urban fabric with the same care, intentionality and respect for soul that was traditionally reserved for temples and holy sites.

Selman traces the current crisis of urbanism to the disenchanted, hyper-rationalizedworldview that has prevailed in the West since the Scientific Revolution of the 16th-17th centuries. By reducing the city to a utilitarian assemblage of functions, modern planning has stripped it of its potential to serve as a vessel for the human spirit, a stage for the unfolding of individual and collective destinies.

To recover this deeper dimension, Selman advocates for a new urban paradigm infused with the insights of depth psychology. This would mean designing cities not just as efficient machines for living, but as symbolic landscapes that reflect and support the full spectrum of human experience – from the mundane to the mythic, the personal to the archetypal.

One infinitnently relevant historical exemple of this approach that Seelman highlights is Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s original 1791 plan for Washington, D.C. Steeped in the symbolic language of sacred geometry, L’Enfant envisioned the capital as an esoteric diagram of the new republic’s highest ideals and aspirations – a trellis for the flowering of democracy and enlightened governance.

At the heart of this vision was the creative tension between the White House as the seat of executive power and the Capitol as the voice of the people, mediated by radiating avenues that suggest an open, dynamic equilibrium. Though largely unrealized in its metaphysical dimensions, L’Enfant’s plan points the way toward an urbanism that gives physical expression to the depths of the psyche.

For Selman, this kind of “ensouled” urbanism is not a matter of imposing a singular vision, but of creating a flexible framework for the emergence of meaning. He imagines the city as a network of “stations” – points of heightened intentionality akin to the Stations of the Cross in a cathedral – that individual citizens can link together into their own narrative journeys.

We choose the built environment as one example here, but this is evident in all other expresions of human culture. Much of human culture is using the reflective lenses of signifiers in the inner and outer world to create reference pooints for the other, in each, that remind us of our greater humanity.

Every act is either an engagement with the real self or a deflection from it. This fundamental choice underlies all forms of art, design, styles of therapy, modes of communication, and ways of being in life. It is the primary decision we make unconsciously before all others. It frames our experience against the backdrop of our inner and outer worlds.

When we deflect, we don’t call these deflections what they are. Instead, we label them as our self, our values, our identity, or things we must do. But they are not us, and they are not real. We deflect in myriad ways: “I didn’t do it,” “I did it, but you did something worse,” “You didn’t do something worse, but you don’t understand how hard I have it,” “I am the ultimate victim, which excuses anything I do; no one can understand me.” We also see deflection in abuses of power that are framed as actually good, with claims that anyone who is hurt simply has a victim complex, implying that abuse doesn’t exist.

We engage in these deflections politically, religiously, therapeutically, and aesthetically all the time. Many movies, shows, and forms of design indulge this tendency. The self is not found solely in the inner world; it is found in the outer world too. We must accept the self paradoxically through the acceptance of the reality of our inner experience and the external world that we cannot control. The self is especially found in the paradox of where these two realities conflict.

In my work as a therapist, I often find myself redirecting subjectivity and objectivity back to their respective domains where they are most effective. Politics and healthcare, for instance, are material realities best approached through an objective lens. Yoga and magic, on the other hand, are subjective practices aimed at generating inner meaning. Both spheres are undeniably real, but one cannot directly influence the other, much as we might sometimes wish otherwise.

Our objective and subjective brains, it seems, evolved to serve different functions. The objective mind maps the external world through empirical cause and effect reasoning. The subjective mind clarifies inner experiences, regulates psychic energy and somatic states, and helps us compensate for the limitations and double binds of an external reality beyond our individual control.

The work of neuroscientist Paul Maclean and Jungian analyst Edward Edinger is particularly illuminating in this regard. Though approaching the issue from the distinct angles of evolutionary psychology and phenomenology respectively, both describe a similar dynamic. They observe that people often resist reckoning with both the objective and subjective aspects of the psyche, instead seeking refuge in one mode of cognition while pretending it can control the other. This tendency, they suggest, is especially pronounced in those with significant trauma histories.

Trauma and intuition, after all, arise from the same subcortical regions of the brain. Much of the political and religous neurosis that has taken root in certain New Age circles can be understood as a misattribution of trauma responses to some form of higher intuitive knowing. Rather than acknowledging the reality of their own wounding, adherents reframe it in a way that lends it an aura of spiritual significance.

This points to the paradoxical nature of spirituality and religious practice, both organized and personal. These pursuits can be profoundly beautiful and transformative. They can also be vehicles for terrible harm and delusion. At the same time, they seem to be an eternal and inevitable feature of the human condition. This is due in large part to the way we intentionally or semi-consciously “cross the wires” between objective and subjective realities through ritual, altered states of consciousness, neurodivergence, and other boundary-dissolving practices.

Ritual, in particular, involves taking symbols from our inner world and enacting them in the outer world, creating a feedback loop of objective and subjective reference points. The goal is to generate a “spicier” cognition that better integrates cognition with the non cognitive parts of human experience. In this state of heightened cognitive arousal, disparate parts of the brain enter into conversation with each other via the reflective and refractive properties of symbolic language. Ritual does this, psychadelics do this, somatic and parts based therapy does this. There is a reason that psychopharmacologically or culturally we create these perrienial experiences that play kalidescope with our cognition in order to heal, leave our own ego limited perspective, and create new ways of growth and being.

This liminal state of consciousness, I believe, is what many mystics and spiritual traditions are gesturing towards when they speak of union, oneness, or non-duality. Its why I think specifying between non duality or dualness in philosophtyy or spirituality is kind of a wate of time. As a therapist I see them as parts of the same phenomenology that feel seperate but are experrienced individually. Therapy worked and still works if we create a novel and emergent mode of cognition made possible by the creative interplay of objective and subjective ways of knowing. It is a neuro-paradox, a psychic achievement rather than a regression. Newer qEEG research shows that event related potentials in the brain crossing the streams of these neuropathways might mean that the neuro paradox is a medical phenomenon.

Cultivating access to this holistic state is the essential ingredient in practices like somatic therapy, parts work, and psychedelic-assisted healing. By temporarily softening the boundaries between mind and body, self and other, these approaches help us metabolize and integrate traumatic experience. But there is always the risk of losing sight of the “as if” quality of the process – of forgetting that we are engaging in a ritual game and mistaking the symbol for the symbolized.

This is the danger of literalizing metaphors, of reifying the products of the imagination. When we forget that our myths and models of the psyche are provisional and perspectival, we become vulnerable to illusions and projections. This is as true for Jung’s own elaborate metapsychology as it is for any other system. The important thing is to hold our theories lightly, to wear them like garments rather than mistaking them for our skin.

The failure to maintain this “negative capability,” to tolerate the ambiguity and uncertainty inherent in any symbolic representation of the psyche, can lead to a kind of logical narcissism – a grandiose belief in the omnipotence of our own subjectivity. Alternatively, it can result in the repression of emotion, the denial of the very real and raw feelings that fuel the drive towards meaning-making in the first place.

These twin pitfalls of subjectivism and objectivism find their political expression in the various “conspirituality” currents mentioned earlier. Those with heightened intuitive capacities due to buut still affected by trauma are especially susceptible to this kind of thinking. Because they have not learned to differentiate between genuine noetic insight and the hypervigilance of the wounded ego, they construct elaborate narratives that validate their own unresolved pain as renactments of abuse as either victim or abuser.

Initially, these narratives can be quite compelling, resonating as they do with the archetypal motifs of the collective unconscious. But over time, they tend to drift in an increasingly rigid and reactionary direction. This is because, at their core, they are driven by a denial of either objective or subjective reality – a refusal to grapple with the complex, messy, and often paradoxical nature of the human condition.

In the therapeutic context, this calls for a kind of holistic, multidimensional approach that addresses the whole person – body, mind, and spirit – and situates individual healing within a larger project of cultural and cosmic transformation. It means recognizing that the metamodern crisis of meaning is not just a personal challenge, but a collective oscillation internaly and externally. When we experience the inner or the outter we are more likley to point at the oppposite and absolve ourselves of guilt. That conceptualization implicates us all in the work of weaving a new mythology.

As we venture into this liminal space between worlds, let us remember the words of the poet Rilke: “The purpose of life is to be defeated by greater and greater things.” May we have the strength to embrace the defeats and the revelations of the therapeutic journey, trusting that in the crucible of the healing relationship, something new and luminous is always waiting to be born.

This is the loosley defined but uncompromising vision of therapy that I believe we must uphold, even in the face of the relentless pressure to standardize and medicalize our work. It is a vision that is rooted in a deep respect for the infinite complexity and indefinable potentiality of the human soul, and in a recognition of the transformative power of authentic conjoined relationship.

Of course, this is easier said than done. In a world that increasingly values quick fixes and measurable outcomes over the slow, messy work of self-discovery, it can be tempting to retreat into the safety of our theories and techniques, to hide behind the armor of professional detachment.

But if we are to be true to our calling as therapists, we must be willing to take the harder path – to step out from behind the mask of expertise and meet our clients in the vulnerable, uncharted territory of the soul. We must be willing to bear witness to their pain and their joy, their despair and their resilience, without judgment or agenda.

This is the essence of what the psychoanalyst Nancy McWilliams calls “the therapeutic attitude” – a stance of deep respect and empathy, grounded in a recognition of our shared humanity. It is an attitude that sees the client not as a problem to be solved, but as a fellow traveler on the path of self-discovery, worthy of our full presence and attention.

Cultivating this attitude requires a kind of ongoing self-reflection and self-care on the part of the therapist. We must be willing to do our own inner work, to confront our own shadows and blind spots, if we are to be fully present to the other. We must learn to listen not only with our minds, but with our hearts and our bodies, attuning ourselves to the subtlest nuances of the therapeutic relationship.

This is a lifelong journey, one that requires a deep commitment to our own growth and healing. But it is also a journey that promises profound rewards – the satisfaction of participating in the unfolding of another’s potential, the joy of witnessing the human spirit in all its resilient beauty.

As the existential psychotherapist Irvin Yalom puts it:

“The therapist’s task is to create a relationship in which the patient feels safe enough to let down his or her defensive armor, examine the feared inner world, and attempt new interpersonal behaviors. In such a relationship the patient can begin to acknowledge the hidden and disowned parts of the self, the split-off affects and impulses that have been repressed because they are too threatening or painful. The patient can come to accept these parts and reintegrate them into a more whole sense of self.”

This, ultimately, is the goal of therapy as I understand it – not to eliminate symptoms or conform to some arbitrary standard of normality, but to help the individual become more fully and authentically themselves. To support them in the lifelong process of integrating the disparate parts of their psyche, of finding meaning and purpose in the face of life’s inevitable challenges and tragedies.

For in the end, therapy is not just a set of skills or techniques, but a way of being in the world – a way of meeting the other in the fullness of their humanity, and allowing ourselves to be transformed by the encounter. It is a way of honoring the ineffable mystery at the heart of the self, and of bearing witness to the unfolding of that mystery over time.

The task of engaging with our inner world, as crucial as it is, remains fraught with difficulty and resistance. For to venture into the depths of the psyche inevitably means confronting those aspects of ourselves that we would prefer to deny, avoid, or project onto others. This is the realm of the shadow – all that we have repressed, rejected, or disowned in ourselves, the “dark side” of our nature that Jung saw as the doorway to the unconscious.

The shadow is not, as popular conception would have it, simply the sum of our worst qualities and impulses. Rather, it is all that we have failed to integrate into our conscious self-image, the parts of ourselves that we deem unacceptable or incompatible with our ideal persona. In trauma therapy I conceptulaize this as emotional arcs, emotions that we are either enmeshed with or avouiidant of. We must develop a comfort with all of our emotions to function as adults. As such, the shadow contains not only our aggressive, selfish, or “negative” aspects, but also our unrealized potentials, our untapped creativity, our hidden strengths.

The work of therapy, from this perspective, is not to eliminate or suppress the shadow, but to bring it into a constructive dialogue with the conscious self. This is a gradual, often painful process of self-examination, as we confront the ways in which we have denied or projected our own darkness onto others. But it is also a profoundly liberating process, as we reclaim the lost or neglected parts of ourselves and move towards a more complete and authentic self-acceptance.

This work takes on a particular urgency in the second half of life, as the psyche naturally turns inward in a bid for wholeness and integration. As Jung observed, the first half of life is typically devoted to the development and strengthening of the ego, as we learn to navigate the challenges of the external world and build our place in society. But at midlife, this outward-focused agenda often falters, as we confront the limitations of our youthful ambitions and the existential questions of meaning and mortality.

Here the shadow emerges as a powerful catalyst for growth, forcing us to reevaluate our priorities, values, and self-image. If we can summon the courage to engage with this material, to “walk through our fear,” we open ourselves to a profound transformation. We discover new dimensions of our being, new sources of vitality and purpose. We develop the negative capability to hold the tension of opposites, to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty. We become, in short, more fully human.

Conversely, if we fail to undertake this shadow work, we risk becoming mired in bitterness, stagnation, and projection. We become increasingly rigid and reactive, clinging to outdated attitudes and persona while unconsciously enacting our shadow through passive aggression, self-sabotage, or scapegoating others. We see this pattern writ large in the political and cultural sphere, where the unacknowledged shadows of individuals coalesce into the toxic miasma of racism, sexism, xenophobia, and environmental destruction.

In this sense, the task of individual shadow work is not separate from the larger project of social and planetary healing. As we learn to take responsibility for our own darkness, to withdraw our projections and bear the tension of our inner conflicts, we contribute to the evolution of human consciousness as a whole. We become agents of creative transformation, midwifing the emergence of new, more integrated ways of being and relating.

This is the promise and potential of depth-oriented therapy in our time – to facilitate this crucial work of self-examination and self-transformation, not as a solipsistic retreat from the world, but as a radical act of engagement with it. For in the end, as Jung understood, the individual and the collective are inextricably intertwined. The path to wholeness is not a private salvation, but a participatory unfolding in which we are all implicated.

At the same time, we cannot simply retreat into a romanticized mysticism that ignores the genuine advances of modern psychology. The challenge is to find a way of working that respects the scientific method without being constrained by scientism – that remains open to the full spectrum of human possibility without lapsing into New Age pablum. This is the dialectical dance that characterizes any mature psychotherapy: between the rational and the intuitive, the objective and the subjective, the psychological and the somatic.

Navigating this tension requires a kind of “negative capability,” in Keats’ famous phrase – a willingness to dwell in uncertainty and ambiguity without rushing to impose premature explanations. It means learning to see the therapeutic encounter not as a procedure but as a poetic co-creation, an improvisational duet between two subjectivities. In this space, the therapist must be less a medical expert than a fellow traveler, a guide intimately acquainted with the terrain of the soul yet humble in the face of its ultimate unknowability.

This perspective is articulated by the existential psychiatrist Irvin Yalom in his book “The Gift of Therapy”:

“Though we therapists traffic in techniques, theories, and methodologies, we are at heart craftsmen of the psyche, not engineers or scientists. Our work is closer to that of the artist, the philosopher, the navigator, or the explorer. The therapist, like the artist, must possess the courage to encounter and engage the world without knowing in advance where that engagement will lead.”

Heidegger’s concept of “Dasein,” or being-in-the-world, emphasizes the importance of authentic engagement with the world around us. He argues that we often fall into the trap of seeing the world through the lens of predetermined categories and concepts, which obscure the true nature of being. In the context of therapeutic work, this means having the courage to let go of our preconceived notions and diagnostic labels, recognizing that they are, at best, provisional sketches of an infinitely complex reality.

Heidegger’s philosophy echoes this sentiment, suggesting that our tendency to confuse our representations of reality with reality itself is a fundamental weakness of the human condition. He argues that we must strive to transcend these limitations and engage with the world in a more authentic, unmediated way.

The poem “The Memory Palace” by Cyberpunk author William Gibson illustrates this idea beautifully. Gibson suggests that throughout human history, we have always been driven to represent phenomenological reality through various objective means, such as stone circles, water clocks, and maps. However, he also acknowledges that these representations can never fully capture the “true weather of days” – the raw, unfiltered experience of being in the world.

However, both Gibson and Heidegger recognize that representation is an unavoidable part of the human experience. We are, as Gibson puts it, “the animal that represents, the sole and only maker of maps.” While our representations may be imperfect, they are nonetheless real and meaningful. They allow us to create “pavilions and palaces, cities and states, arts and sciences” – the endless elaborations of evidence of being.

When we were only several hundred-thousand years old, we built stone circles, water clocks.

Later, someone forged an iron spring.

Set clockwork running.

Imagined grid-lines on a globe.

Cathedrals are like machines to finding the soul; bells of clock towers stitch the sleeper’s dreams together.

You see; so we’ve always been on our way to this new place—that is no place, really—but it is real.

It’s our nature to represent: we’re the animal that represents, the sole and only maker of maps.

And if our weakness has been to confuse the bright and bloody colors of our calendars with the true weather of days, and the parchment’s territory of our maps with the land spread out before us—never mind.

We have always been on our way to this new place—that is no place, really—but it is real.-William Gibson, Memory Palace

We’ve always been on our way to this new place that is no place really but it is real. We represent these things to ourselves and to each other, and out of those feeble representations come pavilions and palaces, cities and states, arts and sciences, and all the endless elaborations of evidence of being. Even though being can never arrive at itself, it can see itself through representation in story and art.

But this alchemical process is always fraught with risk and uncertainty. To engage in it honestly, we must be willing to relinquish our epistemic privilege as experts and authorities. We must learn to listen not only with our theories and techniques, but with the “third ear” of intuition. We must cultivate what the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard called “intimate immensity” – a familiarity with the farther reaches of the psyche that comes not from detached analysis but from a kind of phenomenological indwelling.

In mythological terms, we are called to be both Daedalus and Ariadne – the craftsman of the labyrinth and the holder of the thread. On the one hand, we must be architects of meaning, helping our clients to construct coherent narratives from the welter of their experience. On the other hand, we must also be willing to enter the maze ourselves, to risk getting lost in the twists and turns of the psyche without any preconceived map or agenda.

This is the paradox at the heart of depth-oriented therapy: that in order to midwife the birth of the self, we must first surrender our own egoic certainties. We must learn to inhabit what Keats called “negative capability” – the ability to dwell in “uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Only by relinquishing our Procrustean preconceptions can we create a space for something genuinely new to emerge.

In his book “The Ever-Present Origin,” Jean Gebser outlines a model of the evolution of human consciousness, which he sees as unfolding through a series of distinct “structures” or “mutations.”

Gebser identifies four main structures of consciousness: the archaic, the magical, the mythical, and the mental. Each of these structures represents a different mode of experiencing and interpreting reality, with its own unique characteristics and limitations.

The archaic structure is the most primal and undifferentiated, corresponding to a state of deep oceanic oneness with the world. In the magical structure, the individual begins to differentiate themselves from their environment, but still experiences a strong sense of participation and resonance with the forces of nature. The mythical structure brings a greater sense of separation between self and world, but also a rich imaginative capacity that expresses itself through symbol, metaphor, and narrative.

It is with the emergence of the mental structure, however, that we see the rise of abstract rational thought, the capacity for logical analysis and causal reasoning. This is the structure that has dominated Western consciousness for the past few millennia, reaching its peak in the hyper-rationality of the modern era.

For Gebser, however, the mental structure is not the end point of human evolution. He envisions the emergence of a new, integral structure of consciousness, one that would transcend and include all the previous structures in a higher synthesis. This integral consciousness would not simply reject or suppress the mythical and magical dimensions of experience, but would integrate them with the clarity and discernment of the rational mind.

In the context of psychotherapy, Gebser’s model suggests that true healing and wholeness require more than just a change in cognitive patterns or behavioral habits. It calls for a transformation of consciousness itself, a shift towards a more integrative and multidimensional way of being in the world.

This means working not only with the client’s explicit beliefs and assumptions, but also with the deeper structures of their experience – the imaginal, somatic, and transpersonal dimensions that are often marginalized or pathologized by the mental-rational perspective. It means honoring the wisdom and intelligence inherent in these other modes of knowing, while also bringing the clarity and discernment of the reflective mind to bear on them.

Such an approach requires a willingness on the part of the therapist to move beyond the confines of any single theoretical framework or methodology. It calls for a kind of epistemological humility (honesty) , a recognition that no one perspective can capture the full complexity of the psyche. At the same time, it demands a rigorous and disciplined engagement with the various maps and models that can help us navigate the territory of consciousness.

In this sense, the integral therapist is one who can hold multiple perspectives simultaneously, who can move fluidly between different modes of understanding and intervention as the situation requires. They are attuned not only to the presenting symptoms and problems, but to the deeper developmental potentials and evolutionary currents that are seeking to emerge in the client’s life.

This is not a matter of imposing some preconceived notion of growth or enlightenment, but of listening deeply to the client’s own unique unfolding, to the seeds of wholeness and integration that are already present, even if obscured by layers of conditioning and defense. It is a collaborative and co-creative process, one in which therapist and client together explore the frontiers of consciousness, discovering new possibilities for healing and transformation.

In the consulting room, this means learning to listen not only to the literal content of our clients’ words, but to the music between the lines – the hesitations, the digressions, the metaphors and dreams and flashes of unexpected affect. It means attending to what the psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas called the “unthought known” – the implicit patterns of relating and being that shape our experience without ever being fully articulated.

The self, then, is not a fixed essence or a static set of traits, but a dynamic process of becoming that is always unfolding in relationship to the world. It is a web of stories and memories, desires and fears, that we are constantly weaving and re-weaving throughout our lives.

To work with the self in therapy is to enter into this web, to trace its threads and patterns, to discover the hidden meanings and possibilities that lie within. It is to create a space where the self can be explored and expressed, challenged and affirmed, in all its messy, contradictory glory.

And so, as therapists, our task is not to impose some preconceived notion of health or happiness onto our clients, but to support them in the process of crafting their own unique path through life. We are not the experts on their experience, but rather the companions and guides on their journey of self-discovery.

This is a sacred trust, a profound responsibility. And it is one that requires us to bring the full depth and breadth of our own humanity to the work – to meet our clients not just as professionals, but as fellow travelers on the path of life. Because of deluded self evidenced spiritualists and abusive medical establishments this means that therapists in this cammp probably take critiscsm from both halves of our culture that misunderstand them. They misunderstand them only because the people who misunderstand them misunderstand half of their internal world.Both the purely objective scientific materialists and those that literalize spirituality and believe in magic through projected and unconcious intuition are avoiding a part of self and over identifying with another.

This is the great challenge and the great promise of our work as therapists – to shepherds of the unfolding self within the unfolding society. May we rise to meet it with courage, compassion, and an unwavering commitment to the transformative power of human connection.

As Yalom reminds us:

“Psychotherapy is a unique and profound relational adventure. It brings two people together to engage in an intimate and meaningful exchange. It has the promise of growth, self-discovery, and healing. It is a journey into the depths of the soul, a shared exploration of the most fundamental aspects of human existence. And in that sense it transcends any particular modality or school of thought. In the end, it is a profoundly creative, deeply personal, and uniquely human endeavor.”

This means recognizing that the real work of therapy happens not in the realm of conscious insight or behavioral change, but in the subtle reorganization of the psyche’s implicit structures. In this sense, therapy is less a matter of acquiring new knowledge than of learning to inhabit our existing knowledge differently – of developing what the philosopher Eugene Gendlin called a “felt sense” of our experience, a pre-conceptual awareness that is more than the sum of our explicit beliefs and perceptions.

The late James Hillman, one of the most visionary, but often misguided, thinkers in the depth psychology tradition, put it this way:

“The whole issue of treatment in therapy is not what is done to the patient, what the therapist does, what method is followed, what drugs are prescribed. The real treatment is what happens to the soul-spark, what happens to the vital, creative, generative process within the person. And that can only happen through attention, through witnessing, through reflection, through mirroring back in many ways to the patient the living process that is going on within.”

This “soul-spark,” this “vital, creative, generative process,” is the true subject of therapy – and it is a subject that demands a poetic sensibility as much as a scientific one. To nurture it, we must learn to see our work not merely as a set of techniques and interventions, but as a kind of co-creative, improvisational dance – a “mysterium coniunctionis,” in Jung’s evocative phrase, between the conscious and the unconscious, the known and the unknown.

Cultivating this sensibility requires a willingness to tolerate ambiguity and paradox – to hold the tension between seemingly conflicting perspectives without rushing to resolve them. It means learning to see the therapeutic encounter not as a problem to be solved, but as a koan to be lived. In the words of the Zen master Shunryu Suzuki:

“When you do something, you should burn yourself completely, like a good bonfire, leaving no trace of yourself.”

As a therapist, I try to provoke patients in this way. I push them into their most repressed experiences so they can know that that alienated part of themselves. Please do not come to therapy with me if you do not want change. Ready yourself to be different after therapy or do not come at all. This is the kind of presence that I believe therapy at its best demands – a presence that is fully engaged yet utterly transparent, that brings all of itself to the encounter without imposing any preconceived agenda. It is a quality of attention that is at once deeply personal and radically impersonal, attuned to the unique contours of the individual psyche yet grounded in a transpersonal awareness.

Seen in this light, the future of psychotherapy lies not in the proliferation of new theories or techniques, but in the cultivation of a certain attitude or stance towards the mystery of being. An attitude of radical openness and radical humility, willing to be transformed by the encounter with otherness in all its forms. An attitude that sees therapy not as a way of fixing broken machines, but as a way of awakening to the sheer miracle and tragedy of consciousness itself.

Riddle in the Garden, by Robert Penn Warren is a beautifl and simple explication of this concept. I have used it multiple times to confuse audiences when I give talks on these ideas. Penn Warrren’s history and guilt as a refoormed racist put him in touch with these ideas on a psychic level. These insights are not mine. These truths are part of the perrenial experience of all of those that listen these forces older than humanity and articulate them in their own voice. As therapist we merely become the vessel for a timeless process if wwe can empty ourselves of ourselves enough to hold the true self.

This is the vision of creation and knowledge that the Penn Warren gestures towards in his haunting poem:

My mind is intact, but the shapes

of the world change, the peach

has released the bough and at last

makes full confession, its pudeur

had departed like peach-fuzz wiped off, andWe now know how the hot sweet-

ness of flesh and the juice-dark hug

the rough peach-pit, we know its most

suicidal yearnings, it wants

to suffer extremely, itLoves God, and I warn you, do not

touch that plum, it will burn you, a blister

will be on your finger, and you will

put the finger to your lips for relief—oh, do

be careful not to break that softGray bulge of blister like fruit-skin, for

exposing that inwardness will

increase your pain, for you

are part of this world. You think

I am speaking in riddles. But I am not, forThe world means only itself.

-Robert Penn Warren, Riddle in the Garden

Warren’s uncompromising verse is a fitting epigraph for the kind of therapy I am advocating here – a therapy that dares to dwell in the shadows of truth, in the liminal space between knowing and unknowing, self and world, language and silence. A therapy that recognizes the ultimate inadequacy of all our words and concepts to capture the lived reality of the psyche, yet nonetheless keeps reaching for the true reason for speech.

The Garden is the self here. To not touch the fruit leaves us living like animals but to touch the fruit reveals the true horror. The fruit itself is a painful blister that exposes a bloody inner world not yet ready to be seen or felt. Breaking a blister and breaking a fruit skin are juxtaposed as the same action in the poem. To understand our own inwardness is to bite it before it is ready and peel away the skin that new skin has not yet replaced underneath. We are meant to follow the labyrinth of ourselves inward to a acceptance and a knowing and Penn Warren tells us this is painful.

The truth is the pain until we temporarily feel until we are ready to acknowledge the actual real. There are harsh realities we have to endure when our inner worlds confronts an external reality that it does not have much power over. This lack of relevance or synthesisis between how we feel the outer world “should” work or how the outer world tells the inner world that it “should” be is under all of psychological dysfunction. We “should” nothing. Reality is merely to accept both parts, inner and outer world as they are unflinchingly. In accepting them only we can learn the messy way that they might be fit paradoxically together.

Penn Warren reminds us he does not speak in riddles. Instead he is simple telling us the way the world works. The reader already knows and has accepted this; or they cannot understand this truth yet and think it is a riddle that can be mastered with reasoning and intellect.

It is not however. Notice that there is no serpent in this image of the garden of Eden. Or rather there is a serpent but it is in the ambivalent mind of the speaker, not the in the grass by the tree. The deciet of the serpent is that the poem is a riddle. The serpent is in the belief that it can be mastered or solved “figuring it out”.

Life itself is a swelling. You cannot have one part of the process without accepting all of it. The swelling in the growth of the fruit is also the swelling in the growth of a blister of pain. The peach only exists to be eaten to die. We eat the peach to grow the next one. The peach that has made full confession and rid itself of “pudeur” or shame.

Not to touch the “suicidal” peach is not to touch the awareness of self. For to live is to be hurt and to grow. This process only has the meaning that we allow ourselves to give it. To touch the peach is to become part of the world like Adam and Eve found out. It hurts us, it blisters us, but it turns us into fruit.

“I am the lord your God” is what god tells us in the bible, but here Penn Warren tells us “I am not”. It is only our deflections and intelectualizations that make us pretend to be false Gods instead of accepting the inwardness that can make us divine.

Penn Warren is reminding the readers that people who believe in the intellectual origins of being are still children afraid to pop the blister. The inner world is never ready for the outter world. Our own and other’s psyches must take the leap or get out of the way. Intelectualization is just a deflection from the real work and there is no means of logical preperation.

In the end, this is perhaps the deepest riddle of the therapeutic encounter – the fact that healing happens not through the dispensation of clever interpretations or scientifically empirical foolproof techniques, but through the simple yet profound act of acceptance of the inner and outter world for what they are.

In the end, the task of therapy – and indeed, the task of living – is to cultivate the courage to engage with the real self, in all its complexity and contradiction. This means learning to recognize and resist the countless ways we deflect from this authentic encounter, both individually and collectively.

Every act, every form of expression, every modality of being is either an engagement with the real self or a deflection from it. This is as true in the therapy room as it is in the artist’s studio, the designer’s workshop, or the philosopher’s study. It is the fundamental choice that underlies all others, the riddle at the heart of the human condition.

Too often, we mistake these deflections for the self itself. We call them our values, our identity, our obligations. But they are not us, and they are not real. They are the stories we tell ourselves to avoid the discomfort of confronting our own depths, the masks we wear to navigate a world that feels overwhelming or alien.

The real self is not to be found solely in the inner world of subjective experience, nor solely in the outer world of objective reality. Rather, it emerges in the dynamic interplay between the two, in the paradoxical space where our deepest truths collide with the unyielding facts of existence. It is here, in the crucible of this conflict, that we are called to forge an authentic and integrated selfhood.

This is the great challenge and invitation of a depth-oriented approach to therapy and to life. It demands that we relinquish our illusions of control, that we learn to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty, that we risk vulnerability and disillusionment in the service of a higher truth. It requires us to accept the reality of our inner experience, in all its darkness and light, while also accepting the reality of an external world that we cannot ultimately control.

In practical terms, this means cultivating a new relationship to our own suffering – not seeking to avoid or eliminate it at all costs, but learning to listen to its deeper message and meaning. It means developing the discernment to know when our pain is guiding us towards necessary growth, and when it is merely a siren song luring us towards self-destruction. It means daring to love, to create, to believe, even in the face of loss, rejection, and doubt.

Above all, it means learning to see ourselves and each other with fierce honesty and radical compassion, recognizing that we are all struggling to find our way in a world that often feels like a hall of mirrors. In this recognition lies the possibility of true meeting, true healing, true transformation – not into some perfect or idealized version of ourselves, but into a more fully human, fully alive expression of who we already are.

This is the sacred task to which we are called, as therapists and as human beings – to keep faithfully engaging with the real, even and especially when it shatters our cherished illusions. For it is only in this courageous encounter that we can ever hope to discover the deepest truth of our being, the hidden wholeness that lies beneath the fragments of our lives.

As Rilke so eloquently reminds us:

“Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.”

In the end, this is the only journey worth taking – the journey into the heart of the real, the journey home to ourselves. May we all find the strength and the grace to keep walking, step by uncertain step, into the unknown and unknowable mystery of who we are.

The evil and suffering in the world stems from our failure to acknowledge and integrate our own shadow material – the dark, repressed aspects of our psyche that we deny or project onto others. This avoidance and repression, both on an individual and societal level, creates the conditions for evil to flourish.

In his book “Why Good People Do Bad Things,” Jungian analyst James Hollis explores this theme in depth. He argues that the recognition of our own capacity for evil is the necessary prerequisite for taking responsibility for our choices. Only by facing our own darkness can we begin to make more conscious and ethical decisions. This confrontation with evil, both within and without, is an essential part of the individuation process – the lifelong journey towards wholeness and self-realization.

However, this process of shadow integration is often hindered by the incentive structures and systems we have built into our societies. Bureaucracy, proceduralism, and hierarchies are some of the biggest culprits in this regard. These systems often prioritize conformity, tradition, and the maintenance of the status quo over individual growth and the pursuit of what is good and right in the here and now.

It has been said that all the evil in the world is projected trauma, but this is an oversimplification. While trauma certainly plays a significant role in perpetuating harmful behaviors and belief systems, the root cause lies deeper, in our inability to fully accept and integrate both our inner subjective experiences and the objective realities of the outer world.

This inability is fundamentally caused by our avoidance of or enmeshment with emotional arcs. Emotional arcs are the natural progression of emotions that arise in response to various life experiences. When we have a healthy relationship with our emotions, we allow them to rise, crest, and dissipate, learning from them and integrating their wisdom into our conscious understanding.

However, when we become stuck in an emotional arc, either through avoidance or enmeshment, we create a breeding ground for trauma and dysfunction. Avoidance occurs when we refuse to acknowledge or engage with certain emotions, often because they feel too threatening or overwhelming. Enmeshment, on the other hand, happens when we become so identified with an emotion that we cannot separate ourselves from it, reliving it over and over without resolution.

Both avoidance and enmeshment prevent us from fully processing and completing the emotional arc, leaving us with unresolved wounds that color our perceptions and reactions. These wounds then manifest as an inability to accept certain aspects of our inner world, such as our vulnerability, powerlessness, or anger, as well as aspects of the outer world that trigger these unresolved emotions.

Trauma arises when these unprocessed emotions are repeatedly activated without the opportunity for integration and completion. The traumatized individual becomes stuck in a loop of emotional reactivity, unable to distinguish between past and present, inner and outer reality. This creates a distorted lens through which they view themselves, others, and the world at large.

Evil, in this context, can be understood as the acting out of these traumatic distortions in ways that harm oneself or others. When we are cut off from our own emotional truth, we become more susceptible to inflicting our pain onto others, often in an unconscious attempt to rid ourselves of it. We may also be drawn to ideologies or belief systems that reinforce our emotional avoidance or enmeshment, further perpetuating the cycle of trauma.

However, it is crucial to recognize that not all harmful actions are the direct result of personal trauma. Systemic and institutional factors, such as oppression, inequality, and societal conditioning, also play a significant role in shaping individual and collective behavior. These factors can create environments that foster emotional disconnection and hinder the healthy processing of emotional arcs.

Ultimately, the path to healing and transformation, both on an individual and societal level, lies in cultivating a greater capacity to accept and integrate the full spectrum of our emotional experiences. This requires a willingness to face our own shadows, to feel our way through the difficult and often painful terrain of unresolved emotions, and to develop a more flexible and adaptive relationship with our inner and outer realities.

By learning to complete our emotional arcs, we can begin to dissolve the barriers that keep us isolated and fragmented, both within ourselves and in relation to others. We can develop a more authentic and embodied sense of self, one that is grounded in the wisdom of our emotions rather than the reactivity of our traumas. And we can work towards creating a world that supports and nurtures this emotional intelligence, fostering greater empathy, compassion, and understanding across all divides.

Bureaucracies, in particular, can become breeding grounds for evil, as they allow individuals to diffuse responsibility and avoid personal accountability. As Hannah Arendt argued in her analysis of the Eichmann trial, the greatest evils are often committed not by fanatics or sociopaths, but by ordinary people who simply follow orders and adhere to the rules of the system.

In academia we see a similar dynamic at play. The research-driven establishment, with its emphasis on evidence-based practices and standardized protocols to empericalize the self, can sometimes serve to stifle innovation and creative approaches to healing. It can prioritize procedures, aesthetics, and rituals over human connection, and treat individuals as data points rather than unique, complex beings.