What is a Labyrinth?

“The labyrinth is an ancient symbol that relates to wholeness. It combines the imagery of the circle and the spiral into a meandering but purposeful path.”

– Dr. Sandra Wasko-Flood

Read This Article as a Pdf: What is a Labyrinth

Main Points and Key Ideas:

The labyrinth as an archetypal symbol in human culture and psychology

Jungian interpretations of the labyrinth as a representation of the individuation process

The labyrinth’s relevance in contemporary therapeutic and spiritual practices

The labyrinth as a metaphor for navigating complex global challenges

Various approaches to working with the labyrinth symbol in personal and collective contexts

The labyrinth as a tool for accessing deeper layers of the psyche and collective unconscious

The connection between the labyrinth and other archetypal symbols in Jungian psychology

The labyrinth’s role in literature, art, and creative expression

The relationship between the labyrinth symbol and concepts of wholeness, integration, and transformation

Practical applications of labyrinth work in Jungian analysis and self-exploration

Outline:

Introduction to the Labyrinth

1.1. The Ubiquity of the Labyrinth Motif

1.2. The Labyrinth in Myth, Literature, and Art

1.3. Jung’s Engagement with the Labyrinth Symbol

The Structure and Symbolism of the Labyrinth

2.1. The Centerward Path: Pilgrimage and Transformation

2.2. Daedalus and the Maze: Encountering the Shadow

2.3. Ariadne’s Thread: The Guiding Function of the Self

Jungian Interpretations of the Labyrinth

3.1. The Labyrinth as Mandala: Wholeness and Integration

3.2. Navigating the Labyrinth of Dreams and Active Imagination

3.3. The Labyrinth and the Alchemical Opus

Labyrinth Work in Jungian Practice

4.1. Finger Labyrinths and Portable Designs

4.2. Guided Labyrinth Meditations and Active Imagination

4.3. Collaborative Labyrinth Drawings and Sandplay

Jungian Thinkers and the Labyrinth

5.1. Marie-Louise von Franz: The Labyrinth as Individuation Symbol

5.2. Lauren Artress: Walking the Sacred Path

5.3. Margaret Atwood: The Labyrinth as Literary Motif

Threading the Labyrinth of Meaning

6.1. The Labyrinth as a Symbol for Our Time

6.2. Navigating the Global Labyrinth: Individuation and Collective Renewal

6.3. The Labyrinth and the Mystery of Wholeness

The Labyrinth as Archetypal Symbol

1.1. The Ubiquity of the Labyrinth Motif

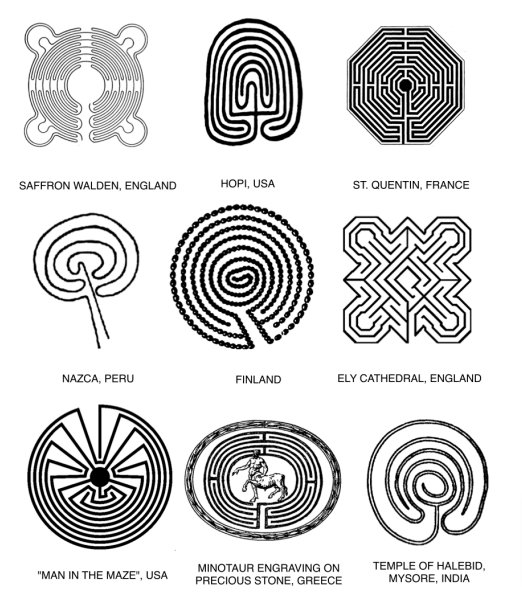

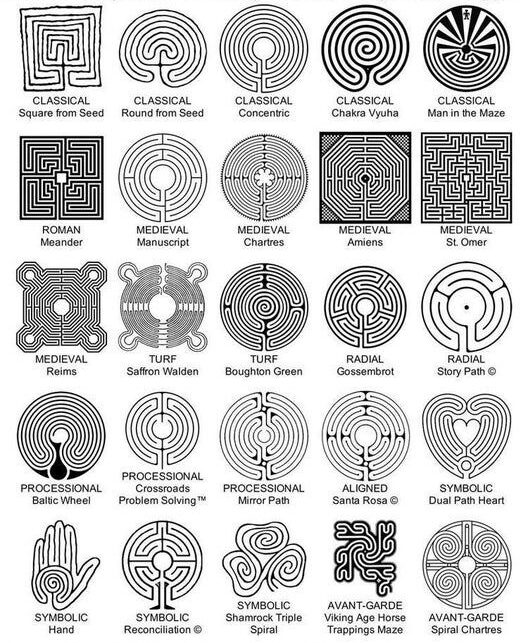

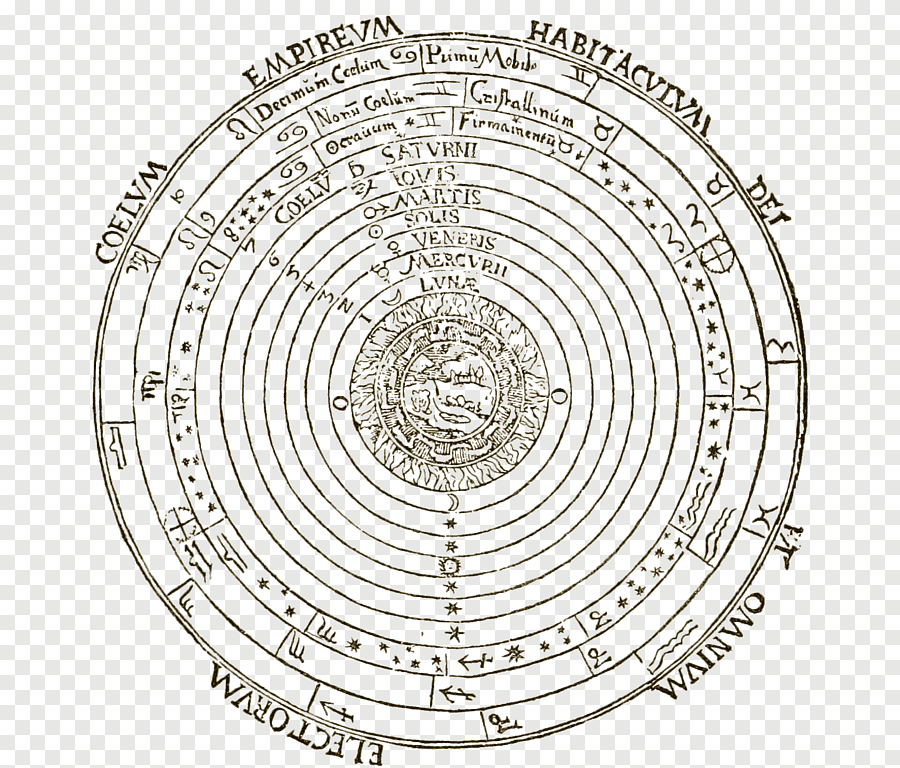

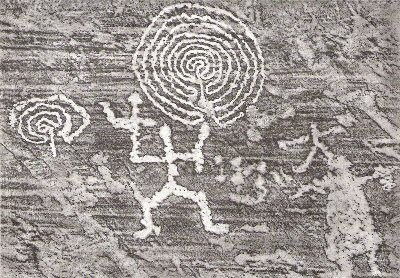

The labyrinth is one of the most ancient and widespread symbols found across human cultures. Appearing as early as the Neolithic period, labyrinth designs have been discovered in various parts of the world, from prehistoric rock carvings and cave paintings to intricate patterns on floors of medieval cathedrals. This universality suggests that the labyrinth is an archetypal motif – a manifestation of what Carl Jung called the “collective unconscious,” the shared psychic heritage of humanity.

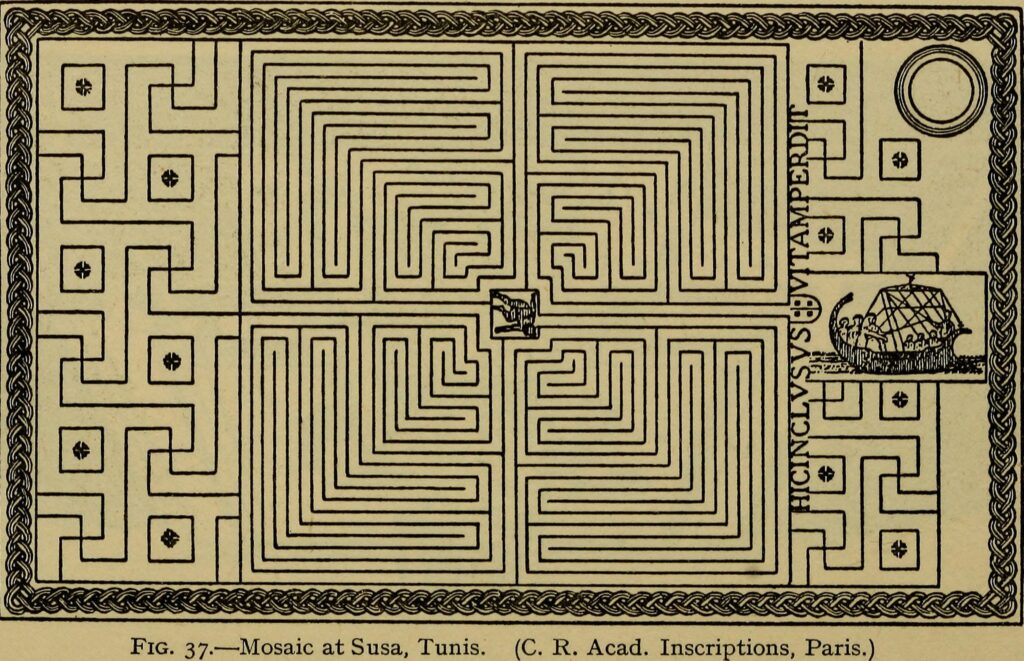

Labyrinth patterns have been found in a astonishing variety of contexts and media throughout history. In ancient Greece, the labyrinth was famously associated with the myth of the Minotaur, the half-man, half-bull monster who dwelt at the center of a labyrinthine structure built by the legendary craftsman Daedalus. This myth was commemorated in labyrinth designs on Cretan coins and in elaborate mosaic floors, such as the famous labyrinth mosaic at the Palace of Knossos.

In ancient Rome, labyrinth mosaics were common decorative features in homes and public buildings, often serving as a protective symbol against evil spirits. The Romans also created turf labyrinths – large-scale labyrinth patterns cut into the grass, which may have been used for walking meditation or ritual dance.

Labyrinth designs also appear in numerous indigenous cultures worldwide, from the Tohono O’odham people of the American Southwest to the Shipibo-Conibo tribes of the Amazon rainforest. In these contexts, the labyrinth often serves as a symbol of the spiritual journey, a metaphorical map of the path to wisdom and transformation.

In medieval Christian Europe, the labyrinth took on new layers of religious significance. Many gothic cathedrals incorporated labyrinth designs into their stone floors, most famously the great labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral in France. These labyrinths were used as substitutes for pilgrimage – by walking the winding path of the labyrinth, the faithful could symbolically trace the arduous route to the holy city of Jerusalem.

The labyrinth also appears as a literary motif in works from diverse cultural traditions. In Dante’s Divine Comedy, the poet’s spiritual journey is figured as a labyrinthine descent into the underworld, with its nine concentric circles of hell. In the epic poems and tales of the British Isles, figures like Gawain, Merlin, and Tristan often encounter magical or perilous labyrinths in the course of their quests. And in the short stories of Jorge Luis Borges, the labyrinth serves as a central metaphor for the infinite complexities and paradoxes of the universe itself.

The persistence of the labyrinth motif across so many cultural contexts points to its deep resonance as an archetypal symbol. Like other universal patterns such as the mandala, the world tree, and the divine child, the labyrinth seems to express something fundamental about the structure of the human psyche and its relationship to the cosmos. Jungian psychology offers a framework for understanding this archetypal significance, and for applying the rich symbolism of the labyrinth to the process of psychic growth and transformation.

1.2. The Labyrinth in Myth, Literature, and Art

“A labyrinth is a symbolic journey . . . but it is a map we can really walk on, blurring the difference between map and world.”

– Rebecca Solnit

In myth, literature, and art, the labyrinth has long served as a rich metaphor for the complex journey of life, with its winding paths, its twists and turns, its movement toward a hidden center. The most famous labyrinth myth is undoubtedly that of Theseus and the Minotaur from ancient Greece. In this tale, the hero Theseus volunteers to be one of the seven young men and seven maidens sent as a sacrificial tribute to King Minos of Crete. These youths are destined to be devoured by the Minotaur, the monstrous half-man, half-bull that dwells in the center of the labyrinth built by Daedalus.

With the help of Ariadne, King Minos’ daughter, Theseus is able to navigate the labyrinth and slay the Minotaur. Ariadne gives him a ball of thread, which he unwinds as he moves through the labyrinth’s winding passages. After defeating the monster, he is able to retrace his steps by following the thread back out of the maze.

This myth is rich in symbolic significance from a Jungian perspective. The labyrinth can be seen as a representation of the psyche itself, with its complex twists and turns, its hidden depths and dark recesses. The Minotaur represents the shadow aspect of the psyche – those repressed, bestial energies that we fear and keep hidden away. Theseus’ journey into the labyrinth is thus a metaphor for the process of confronting and integrating the shadow, a necessary step on the path of individuation.

Ariadne’s thread, meanwhile, symbolizes the guiding function of the Self, the regulating center of the psyche. Just as the thread allows Theseus to find his way back out of the maze, so does the Self offer orientation and meaning amid the confusion of the individuation process. By staying connected to this inner wisdom, one can successfully navigate the labyrinth of the unconscious and emerge transformed.

The labyrinth also appears as a significant motif in medieval literature, particularly in the Arthurian romances. In the 13th-century poem “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” for instance, the hero Gawain must navigate a treacherous labyrinth en route to his confrontation with the mysterious Green Knight. Here, the labyrinth serves as a test of character, a symbolic ordeal that the hero must endure in order to prove his worth.

In Dante’s Divine Comedy, the labyrinth takes on cosmic proportions. The poet’s journey through the nine circles of hell is a kind of metaphysical labyrinth, a winding descent into the depths of sin and suffering. At the same time, this infernal labyrinth is mirrored by the celestial “labyrinth” of paradise, with its nine concentric spheres ascending to the Empyrean. The labyrinthine structure of Dante’s universe thus reflects the complex interplay of opposites – light and dark, good and evil, ascent and descent – that characterizes the journey of the soul.

In the 20th century, the labyrinth emerged as a powerful symbol in the works of modernist writers and artists. The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges was particularly fascinated by the labyrinth, using it as a central metaphor in stories like “The Garden of Forking Paths” and “The Library of Babel.” For Borges, the labyrinth represented the infinite complexity of reality, the dizzying multiplicity of possible paths and outcomes that the mind must navigate.

In the visual arts, the labyrinth has been a recurring motif from ancient times to the present. Labyrinth patterns appear in the intricate knot-work of Celtic art, in the elaborate tile mosaics of Islamic architecture, and in the abstract expressionist paintings of modern artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Tobey. In each case, the labyrinth seems to express something of the artist’s inner world, the complex web of thoughts, emotions, and intuitions that must be navigated in the creative process.

The labyrinth has also been used as a tool for performance and conceptual art. In the 1970s, the American artist Robert Morris created a series of large-scale labyrinth installations, inviting viewers to physically enter and explore these disorienting structures. More recently, the British artist Mark Wallinger created a massive labyrinth design on the floor of the London Underground, transforming the daily commute into a symbolic journey of self-discovery.

These varied artistic engagements with the labyrinth point to its enduring power as a symbol of the creative process itself. The winding path of the labyrinth mirrors the artist’s journey into the depths of the imagination, the twists and turns of the creative psyche. By tracing the labyrinth’s convoluted form, the artist enacts the mysterious process by which the inner world is given shape and meaning.

1.3. Jung’s Engagement with the Labyrinth Symbol

“In the labyrinth of life, we all travel our own unique path.”

– Anthon St. Maarten

Carl Jung himself was deeply fascinated by the labyrinth, recognizing its profound psychological significance. He saw in its convoluted form a powerful representation of the circuitous path of individuation – the lifelong process of psychic growth and self-realization. For Jung, navigating the labyrinth of the psyche, with its blind alleys and sudden turns, was an essential part of the quest for wholeness and meaning.

Jung’s interest in the labyrinth was in part inspired by his own visionary experiences. In his autobiographical work Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung recounts a pivotal dream in which he descends into a dark, twisting cave. At the bottom of this labyrinthine passage, he discovers a glowing crystal – a symbol of the radiant core of the Self. This dream had a profound impact on Jung, confirming his intuition of the psyche’s hidden depths and the transformative power of the unconscious.

Jung also encountered the labyrinth motif in his extensive study of alchemical texts and symbols. In the enigmatic diagrams of the alchemists, Jung discovered numerous labyrinth-like patterns, which he interpreted as symbolic representations of the winding process of psychic transformation. The alchemical opus, with its phases of dissolution, purification, and coagulation, was itself a kind of labyrinth – a tortuous path leading to the creation of the philosopher’s stone, the symbol of wholeness and enlightenment.

In his theoretical writings, Jung often used the labyrinth as a metaphor for the complexities of the psyche. In his essay “The Structure of the Psyche,” for instance, Jung compares the psyche to a labyrinthine structure with many layers and chambers. He writes:

“The psyche is a self-regulating system that maintains its equilibrium just as the body does. Every process that goes too far immediately and inevitably calls forth compensations, and without these there would be neither a normal metabolism nor a normal psyche. In this sense the psyche is a labyrinth, for the labyrinth is a paradoxical structure in which the way in is simultaneously the way out. Whoever travels the labyrinth must therefore constantly turn back and retrace his steps as though returning to the beginning.”

This passage beautifully encapsulates Jung’s understanding of the labyrinth as a symbol of the psyche’s inherent complexity and paradoxical nature. The path of individuation is not a straight line but a winding, recursive process, full of detours and reversals. Just as the labyrinth walker must continually double back and retrace their steps, so must the individual pursuing wholeness continually return to the beginning, confronting the same challenges and mysteries at ever-deeper levels.

Jung also saw the labyrinth as a symbol of the collective unconscious – the universal psychic substrate that underlies all individual psyches. In his view, the labyrinth represented the common spiritual heritage of humanity, the shared patterns and motifs that emerge spontaneously in the myths, dreams, and visions of people across cultures and throughout history. By engaging with the labyrinth symbol, Jung believed, the individual could tap into this collective wisdom and gain insight into the deeper structures of the psyche.

For Jung, the ultimate goal of the labyrinth journey was the discovery of the Self – the regulating center of the psyche that guides the process of individuation. This Self is often symbolized by a hidden treasure or a divine child, something infinitely precious yet difficult to attain. In the myth of the Minotaur, this is represented by the sword that Theseus finds at the labyrinth’s center, which he uses to slay the beast. In alchemical symbolism, it is the philosopher’s stone, the miraculous substance that transforms base matter into gold.

Attaining the Self requires a willingness to confront the shadows and dead ends within one’s own psyche – to face the Minotaur in the labyrinth of the unconscious. This is a daunting and often terrifying task, but one that Jung saw as essential to the individuation process. Only by descending into the depths and facing the darkness can one hope to emerge into the light of wholeness.

At the same time, Jung emphasized that the labyrinth journey is not a solitary one. Just as Theseus had Ariadne’s thread to guide him, so does the individual on the path of individuation have the support of the collective unconscious and the wisdom of the Self. By staying connected to this inner guidance, one can find one’s way through even the most bewildering twists and turns of the psyche.

Jung’s engagement with the labyrinth symbol thus offers a rich framework for understanding the complexities of the individuation process. It reminds us that the path to wholeness is rarely straightforward, that we must be willing to confront the shadows and paradoxes within ourselves. At the same time, it offers the reassurance that we are not alone on this journey – that there is a greater wisdom guiding us, if only we have the courage to trust it.

2. The Structure and Symbolism of the Labyrinth

“The point of a maze is to find its center. The point of a labyrinth is to find your center.”

2.1. The Centerward Path: Pilgrimage and Transformation

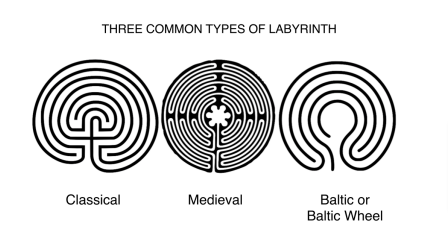

In its classical form, the labyrinth is a single, meandering path that leads inevitably to a central point, despite its many twists and turns. This unicursal design differentiates the labyrinth from the maze, which has branching passages and dead ends. The labyrinth’s centerward motion evokes the idea of pilgrimage – a sacred journey inward to the core of one’s being. Walking the labyrinth becomes a metaphor for the process of transformation, a meditative practice that mirrors the soul’s winding path to self-discovery.

The idea of the labyrinth as a pilgrimage path has deep roots in Western spiritual tradition. In medieval Christianity, labyrinths were often constructed in churches and cathedrals as a symbolic substitute for the pilgrimage to Jerusalem. The most famous of these is the great labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral in France, which measures over 40 feet in diameter and is laid into the stone floor of the nave.

For the medieval pilgrim, walking the labyrinth was a way of enacting the spiritual journey in microcosm. The winding path symbolized the challenges and setbacks of the spiritual life, the twists and turns that the soul must navigate on its way to union with the divine. At the same time, the labyrinth’s unicursal design offered the assurance that the path, however convoluted, would ultimately lead to the center – to the presence of God symbolized by the altar at the heart of the cathedral.

This idea of the labyrinth as a container for the spiritual journey has been taken up by contemporary writers and practitioners. Lauren Artress, an Episcopal priest and psychotherapist, has been a leading figure in the modern labyrinth revival. In her book Walking a Sacred Path: Rediscovering the Labyrinth as a Spiritual Practice, Artress describes the labyrinth as a “divine imprint,” a universal pattern that reflects the structure of the soul’s journey to wholeness.

For Artress, walking the labyrinth is a form of “body prayer,” a way of engaging the whole self in the act of meditation. By following the winding path with focused attention, the walker can quiet the mind and open to a deeper level of awareness. The physical movement of the body through the labyrinth’s turns and counter-turns mirrors the psyche’s journey through the complexities of the inner world.

At the same time, Artress emphasizes that the labyrinth walk is not a solitary practice but a communal one. When we walk the labyrinth, we join a long lineage of pilgrims who have trodden the same path before us. We tap into the collective wisdom of the human spirit, the shared longing for meaning and connection that has driven seekers throughout the ages.

This sense of the labyrinth as a communal pilgrimage is beautifully expressed by the writer and Episcopal priest Alan Jones, in his book Soul Making: The Desert Way of Spirituality:

“The labyrinth is a spiritual teaching tool, a crucible for transformation, as well as a training ground for psycho-spiritual growth and development. Each person’s walk becomes a metaphor for his or her spiritual journey. In surrendering to the winding path, the soul finds healing and wholeness.”

Jones’ vision of the labyrinth as a crucible for transformation points to its alchemical significance. In the enigmatic symbolism of the alchemists, the labyrinth often represented the vessel in which the great work of spiritual transmutation took place. By entering the labyrinth of the soul, the alchemist submitted himself to a process of dissolution and reconstitution, dying to his old self in order to be reborn in a new form.

This alchemical understanding of the labyrinth journey is echoed in the work of Jungian analyst Sylvia Brinton Perera. In her book Descent to the Goddess: A Way of Initiation for Women, Perera describes the labyrinth as a feminine symbol of transformation, a container for the descent into the underworld of the psyche. By surrendering to the labyrinth’s winding path, the seeker undergoes a process of dissolution and regeneration, shedding the false self in order to be reborn into a new wholeness.

For Perera, this labyrinthine descent is a necessary part of the individuation process, particularly for women. In a patriarchal society that values linear progress and goal-oriented action, the labyrinth offers a different model of growth –

one that honors the cyclical, recursive nature of the soul’s journey. By embracing the labyrinth’s winding path, women can reclaim the transformative power of the feminine, the wisdom of the dark and the deep.

The labyrinth’s centerward path thus serves as a powerful symbol of the transformative journey of the soul. By walking its winding course with intention and openness, we can tap into a deeper wisdom, a more authentic sense of self. We can shed the layers of conditioning and false identity that keep us trapped in old patterns, and emerge renewed, reborn into a greater wholeness.

At the same time, the labyrinth reminds us that transformation is not a straightforward process. It requires a willingness to surrender control, to trust the winding path even when it seems to be leading us astray. It invites us to embrace the mystery at the heart of the journey, the sense that our destination is always just out of sight, around the next bend.

In this way, the labyrinth serves as a powerful tool for cultivating what the Zen tradition calls “beginner’s mind” – a state of openness and curiosity, a willingness to be surprised by what we encounter on the path. By approaching the labyrinth with this sense of freshness and possibility, we can open ourselves to the transformative power of the journey, the way in which even the most familiar terrain can become new again when seen with eyes of wonder.

2.2. Daedalus and the Maze: Encountering the Shadow

“A labyrinth has only one path and you cannot get lost. The way in is the way out. They are a great way to relax and meditate.” – Pearl Howie

At the same time, the labyrinth’s complex windings also suggest a confrontation with the shadow – those dark, repressed aspects of the psyche that must be integrated for wholeness to emerge. In Greek mythology, the labyrinth is the domain of the Minotaur, the monstrous half-man, half-bull that Theseus must slay. This fearsome creature can be seen as a symbol of the unacknowledged beast within, the primitive impulses and traumatic wounds that lurk in the labyrinthine depths of the unconscious.

The figure of Daedalus, the legendary craftsman who designed the labyrinth, adds another layer of shadow symbolism to the myth. Daedalus is a complex and ambiguous character, a brilliant inventor who is also capable of great hubris and cruelty. It is Daedalus who builds the wooden cow that allows Queen Pasiphae to mate with the white bull of Poseidon, thus giving birth to the Minotaur. And it is Daedalus who devises the labyrinth as a prison for the monstrous offspring, a way of containing the shame and guilt of the royal family.

In this sense, Daedalus can be seen as a shadow figure, a representation of the ego’s capacity for deception and self-deception. Like the ego, Daedalus is skilled at constructing elaborate defenses to keep the shadow at bay, at hiding the unacceptable aspects of the self behind a façade of cleverness and control. But just as the labyrinth ultimately fails to contain the Minotaur, so too do the ego’s defenses inevitably break down, forcing a confrontation with the repressed material of the unconscious.

This confrontation with the shadow is a central theme in the work of Jungian analyst Robert Johnson. In his book Owning Your Own Shadow: Understanding the Dark Side of the Psyche, Johnson describes the shadow as the “disowned self,” the aspects of the personality that we reject or deny because they don’t fit with our conscious self-image. These shadow qualities are often primitive, irrational, and destructive – the rage, fear, and shame that we keep hidden away in the labyrinth of the psyche.

For Johnson, encountering the shadow is an essential part of the individuation process. By facing the Minotaur within, we can begin to integrate the disowned parts of ourselves, to reclaim the energy and vitality that we have repressed. This is a frightening and often painful process, but it is necessary if we are to move towards wholeness and authenticity.

Johnson emphasizes that the shadow is not simply a repository of negative qualities, but also a source of creativity and renewal. The shadow contains not only our darkest impulses, but also our untapped potential, the parts of ourselves that we have neglected or denied. By engaging with the shadow, we can tap into this hidden wellspring of vitality, and bring new dimensions of the self into being.

This idea of the shadow as a source of renewal is echoed in the work of Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz. In her book Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales, von Franz explores the ways in which folktales and myths often depict the hero’s encounter with the shadow as a necessary prelude to transformation. The hero must face the dark powers within himself before he can claim his true identity and fulfill his destiny.

Von Franz points out that this encounter with the shadow often takes place in a labyrinthine setting – a dark forest, a winding cave, a treacherous underworld. These labyrinthine spaces symbolize the twisting paths of the unconscious, the hidden recesses of the psyche where the shadow dwells. By entering these shadowy realms, the hero sets in motion the process of his own transformation, the death and rebirth that will lead to a new wholeness.

In many tales, the hero’s encounter with the shadow takes the form of a battle with a monstrous beast – a dragon, a giant, a fearsome creature that guards the treasure of the Self. This battle can be seen as a metaphor for the ego’s struggle with the shadow, the way in which the conscious mind must confront and overcome the dark powers of the unconscious in order to claim its true nature.

But von Franz emphasizes that this battle is not a simple matter of conquest or domination. The hero must not only defeat the monster, but also learn from it, integrate its wisdom and power into his own being. This is the paradox of the shadow encounter: the very qualities that we most fear and reject in ourselves are often the key to our own transformation, the hidden treasure that we must claim if we are to become whole.

This idea is beautifully expressed in the Grimms’ fairy tale “The Spirit in the Bottle,” which von Franz analyzes in her book. In this story, a young woodcutter discovers a bottle containing an imprisoned spirit. When the woodcutter releases the spirit, it threatens to kill him – but the clever youth tricks the spirit back into the bottle, and refuses to release it again until it promises to reward him.

Von Franz interprets this tale as a metaphor for the ego’s encounter with the shadow. The imprisoned spirit represents the repressed energy of the unconscious, the dark power that the ego has kept bottled up out of fear. By releasing this energy, the ego runs the risk of being overwhelmed – but by engaging with it creatively, it can harness the shadow’s power and use it for its own growth.

This creative engagement with the shadow is the key to navigating the labyrinth of the psyche. Rather than simply fleeing from the Minotaur within, or trying to slay it outright, we must learn to relate to it with curiosity and compassion. We must be willing to descend into the labyrinth of the unconscious, to explore its winding paths with an open heart and a courageous spirit.

This is the lesson of Theseus, the hero who ventures into the labyrinth to face the Minotaur. Theseus does not simply rely on brute strength to defeat the beast, but rather on the feminine wisdom of Ariadne, who gives him the thread that will guide him back out of the maze. This thread can be seen as a symbol of the ego’s connection to the Self, the inner guidance that allows us to navigate the twists and turns of the shadow realm without losing our way.

By following this thread of inner wisdom, we can begin to integrate the shadow, to reclaim the lost parts of ourselves that we have hidden away in the labyrinth of the unconscious. We can learn to face our darkest fears and desires, to embrace the full complexity of our being. And in doing so, we can tap into a deeper creativity, a more authentic sense of self.

This is the transformative power of the labyrinth, the way in which it can lead us through the shadow realm to a new wholeness. By embracing its winding path, we can begin to dissolve the rigid divisions between light and dark, good and evil, conscious and unconscious. We can learn to see the beauty in the beast, the wisdom in the wound.

2.3. Ariadne’s Thread: The Guiding Function of the Self

“Labyrinths represent the divine feminine womb, a place of rebirth.”

– Alana Fairchild

Yet the myth of the labyrinth also provides a key to navigating this perilous inner landscape: Ariadne’s thread, the lifeline that enables Theseus to find his way back out of the labyrinth after his ordeal. In Jungian terms, this guiding thread can be understood as the Self – the regulating center of the psyche that offers direction and meaning amid the confusion of the individuation process.

The Self is a complex and paradoxical concept in Jungian psychology. It is not the ego, the conscious “I” that we identify with, but rather the totality of the psyche, the greater whole that encompasses both conscious and unconscious elements. The Self is the archetype of wholeness, the organizing principle that gives coherence and direction to the individuation process.

At the same time, the Self is not a static or monolithic entity, but rather a dynamic, unfolding process. It is the “God within,” the divine spark that animates the psyche and guides it towards its fullest realization. The Self is both the goal of the individuation process and the guiding force that leads us there, the alpha and omega of the psyche’s journey to wholeness.

In the myth of the labyrinth, Ariadne’s thread can be seen as a symbol of the Self’s guiding function. Just as the thread allows Theseus to find his way back out of the maze, so does the Self offer orientation and direction amid the twists and turns of the individuation process. By staying connected to this inner wisdom, we can navigate the labyrinth of the psyche without losing our way.

This idea of the Self as a guiding thread is beautifully expressed by the Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz, in her book The Interpretation of Fairy Tales:

“The Self is the innermost nucleus of the psyche, the God-image, the archetype of orientation and meaning. It is the stable center which gives coherence and significance to the often chaotic and contradictory multiplicity of the psychic process. The realization of the Self is the goal of the individuation process, and this is symbolically represented in dreams and myths by the motif of the hidden treasure, the pearl of great price, the golden flower, or the elixir of life.”

For von Franz, the Self is the hidden treasure at the heart of the labyrinth, the precious gem that we seek through all the winding paths of the individuation process. It is the philosopher’s stone of the alchemists, the miraculous substance that transforms lead into gold, darkness into light, chaos into order.

But like any treasure, the Self must be sought after with diligence and devotion. It is not something that we can grasp easily or possess fully, but rather a mystery that unfolds gradually, as we deepen our relationship to the unconscious and learn to trust its wisdom. The path to the Self is a labyrinthine one, full of false starts and dead ends, detours and reversals.

This is where Ariadne’s thread comes in – the intuitive guidance that keeps us oriented towards the Self, even when the way seems obscure. Like Theseus, we must learn to trust this inner thread, to follow it faithfully even when it leads us into dark and unfamiliar territory. We must be willing to face the Minotaurs and shadows within, knowing that the thread will ultimately lead us back to the light.

This trust in the Self’s guiding wisdom is a central theme in the work of Jungian analyst Edward Edinger. In his book Ego and Archetype, Edinger describes the individuation process as a spiral path, a cyclical movement between the ego and the Self. The ego, in its quest for autonomy and mastery, inevitably separates itself from the Self, becoming lost in the labyrinth of its own illusions and defenses. But through the guidance of the Self, the ego can begin to reconnect with its divine ground, to spiral back towards the center of its being.

For Edinger, this spiral path is marked by a series of “ego-Self conjunctions,” moments of alignment and synchronicity in which the ego recognizes its deeper connection to the Self. These conjunctions often come in the form of dreams, visions, or synchronistic events that offer a glimpse of the Self’s guiding presence. By paying attention to these messages from the unconscious, the ego can begin to align itself with the Self’s will, to follow the thread of its own destiny.

But Edinger cautions that this alignment with the Self is not a one-time event, but rather an ongoing process of attunement and surrender. The ego must learn to let go of its attachment to control, to trust the wisdom of the unconscious even when it contradicts its own desires and expectations. This is the paradox of individuation: the more we seek to assert our own will, the more we become lost in the labyrinth of the psyche; but the more we surrender to the Self’s guidance, the more we find our true path.

This surrender to the Self is beautifully symbolized by the figure of Ariadne herself. In the myth, Ariadne falls in love with Theseus and helps him to navigate the labyrinth, but she is ultimately abandoned by him on the island of Naxos. This abandonment can be seen as a metaphor for the ego’s necessary separation from the Self, the way in which it must ultimately let go of its attachment to the divine in order to become fully individuated.

But the myth also tells us that Ariadne is eventually rescued by the god Dionysus, who marries her and places her wedding crown in the heavens as the constellation Corona Borealis. This suggests that even in the depths of abandonment and despair, the Self is still guiding us, still offering its divine love and protection. By surrendering to this greater wisdom, we can find our way back to the center of the labyrinth, back to the wholeness and meaning that we seek.

This idea of surrender to the Self is a central theme in the work of Jungian analyst Helen Luke. In her book Old Age, Luke describes the process of aging as a labyrinthine journey, a descent into the depths of the psyche in search of the Self’s guidance. For Luke, the key to navigating this journey is a willingness to let go of the ego’s attachments and illusions, to embrace the darkness and uncertainty of the unknown.

Luke writes:

“The labyrinth of old age leads us inexorably towards the center where the secret of life is hidden. The nearer we come to the center, the more we have to give up. First we have to give up the illusion that we are in control of our lives. Then we have to give up the illusion that we are separate from the world around us. Finally, we have to give up the illusion that we are separate from God.”

For Luke, the labyrinth of aging is a spiritual path, a journey of surrender and transformation. By letting go of our attachment to the ego and its illusions, we can begin to align ourselves with the Self’s greater wisdom, to find the hidden treasure at the heart of the psyche.

This treasure is not something that we can possess or control, but rather a mystery that we must learn to trust and serve. It is the pearl of great price that we must be willing to sell everything for, the kingdom of heaven that we must become as children to enter. By following the thread of the Self’s guidance, we can begin to embody this mystery, to live from the center of our being.

3. Jungian Interpretations of the Labyrinth

“Like a labyrinth, reality had its ambushes, its dead ends, its quicksand pits, and its ultimate clarity.”

– Avijeet Das

3.1. The Labyrinth as Mandala: Wholeness and Integration

Jung himself drew extensively on labyrinth symbolism in his writings and personal reflections. He saw the labyrinth as a type of mandala – a circular, geometric pattern that represents the Self’s striving for unity and integration. Just as the disparate paths of the labyrinth converge at the center, so too do the fragmented aspects of the psyche find their way to wholeness through the individuation process.

The mandala is one of Jung’s most important and enduring symbols, a cross-cultural motif that he saw as a universal expression of the Self’s healing and integrating power. In his essay “Concerning Mandala Symbolism,” Jung describes the mandala as a “psychological expression of the totality of the self,” a symbol of the psyche’s inherent tendency towards wholeness and balance.

For Jung, the mandala is not just a static image, but a dynamic, living process – a blueprint for the psyche’s growth and transformation. By engaging with mandala symbolism, either through art-making, active imagination, or dream analysis, the individual can begin to align themselves with the Self’s natural movement towards integration, to bring the disparate elements of the psyche into a harmonious whole.

This idea of the mandala as a transformative process is beautifully expressed by Jungian analyst Judith Harris, in her book Jung and Yoga: The Psyche-Body Connection. Harris describes the mandala as a “cosmic diagram,” a sacred pattern that reflects the order and harmony of the universe. By aligning ourselves with this cosmic order, we can begin to heal the splits and divisions within our own psyche, to find our place in the greater whole.

Harris writes:

“The mandala is a symbol of the Self, the totality of the personality, which includes both the conscious and the unconscious. It is a symbol of wholeness, of the union of opposites, and of the integration of the personality. The mandala is a cosmic diagram, a pattern of the universe, which is reflected in the individual psyche. It is a symbol of the path to the center, to the Self, and to the divine.”

For Harris, the mandala and the labyrinth are closely related symbols, both representing the Self’s movement towards wholeness and integration. Just as the mandala is a cosmic diagram of the universe’s order, so too is the labyrinth a sacred map of the psyche’s journey to the center. By walking the labyrinth with an attitude of openness and surrender, we can begin to align ourselves with the Self’s natural wisdom, to find the hidden order within the chaos of the unconscious.

This idea of the labyrinth as a mandala of the Self is echoed in the work of Jungian analyst Lauren Artress. In her book Walking a Sacred Path: Rediscovering the Labyrinth as a Spiritual Tool, Artress describes the labyrinth as a “divine imprint,” a universal pattern that reflects the structure of the psyche. By walking the labyrinth with intention and mindfulness, we can begin to access the deeper layers of the unconscious, to bring the shadow elements of the psyche into the light of awareness.

Artress writes:

“The labyrinth is a mandala that meets our longing to find our way and connect with the Sacred. It is an archetype of wholeness that helps us rediscover the depths of our souls. Walking the labyrinth is a spiritual practice that integrates body and soul, drawing us ever closer to our authentic selves.”

For Artress, the labyrinth is not just a symbol of the Self, but a practical tool for Self-realization – a way of embodying the individuation process through the physical act of walking. By surrendering to the labyrinth’s winding path, we can begin to let go of the ego’s need for control and mastery, to trust in the greater wisdom of the Self. We can learn to embrace the twists and turns of the journey, knowing that each step brings us closer to the center of our being.

This embodied approach to labyrinth work is a key aspect of Artress’ teaching. She emphasizes the importance of walking the labyrinth with the body, not just the mind – of allowing the physical movement to guide and inform the inner journey. By paying attention to the sensations and rhythms of the body as we walk, we can begin to access a deeper level of intuitive guidance, to connect with the Self’s nonverbal wisdom.

Artress also stresses the communal dimension of labyrinth walking, the way in which it can foster a sense of connection and solidarity among seekers. When we walk the labyrinth together, we create a shared field of intention and presence, a collective mandala of the Self. We recognize that we are not alone on the journey, but part of a greater whole – a community of souls all seeking the same center.

This idea of the labyrinth as a collective mandala is beautifully expressed by Jungian analyst Sylvia Brinton Perera, in her essay “The Labyrinth: A Walking Meditation.” Perera describes the labyrinth as a “container for the group psyche,” a sacred space where individuals can come together to share their stories and struggles, to support each other on the path to wholeness.

Perera writes:

“The labyrinth holds the group psyche, providing a safe container for the expression of what is unfolding within each individual and within the group as a whole. It allows for the emergence of a group wisdom that is greater than the sum of its parts. As individuals share their experiences and insights, a collective story begins to take shape – a living mandala of the group’s journey to the center.”

For Perera, the labyrinth is not just a personal tool for individuation, but a social and cultural one as well – a way of fostering connection and understanding across differences, of building bridges between the individual and the collective. By walking the labyrinth together, we can begin to heal the wounds of separation and alienation, to find our place in the greater web of life.

3.2. Navigating the Labyrinth of Dreams and Active Imagination

“Labyrinths are divine conduits for healing and enlightenment.”

– Alana Fairchild

In Jung’s own visionary experiences and dreamwork, labyrinthine imagery played a significant role. He recounts, for instance, a pivotal dream in which he descends into a dark, twisting cave, at the bottom of which he discovers a glowing crystal – a symbol of the radiant core of the Self. Such labyrinthine dreams, Jung believed, could serve as gateways to the unconscious, inviting the dreamer to embark on a transformative inner journey.

The idea of the dream as a labyrinth of the psyche is a central one in Jungian psychology. For Jung, dreams were not simply random neurological events, but meaningful messages from the unconscious – symbolic expressions of the psyche’s deeper wisdom and guidance. By engaging with the images and emotions of the dream, the individual could begin to navigate the labyrinthine depths of the unconscious, to uncover the hidden treasures of the Self.

This process of dream exploration is closely related to Jung’s technique of active imagination – a form of meditative dialogue with the unconscious that he developed as a way of bridging the gap between the ego and the Self. In active imagination, the individual enters into a waking dream state, allowing the images and figures of the unconscious to arise spontaneously in the mind’s eye. By engaging with these inner characters and landscapes, the individual can begin to integrate the split-off aspects of the psyche, to bring the shadow elements into conscious awareness.

The labyrinth is a potent symbol for this process of active imagination, as it represents the winding, recursive path of the psyche’s inner journey. By following the thread of the dream or vision, the individual can begin to navigate the twists and turns of the unconscious, to confront the obstacles and challenges that arise along the way. Just as Theseus had to face the Minotaur at the center of the labyrinth, so too must the individual confront the fearsome and overwhelming aspects of the psyche, the dark and primitive forces that threaten to overwhelm the ego.

But like Theseus, the individual on the path of active imagination is not alone in this confrontation. They have the guidance of the Self, the inner wisdom that is symbolized by Ariadne’s thread. By staying connected to this thread of intuitive guidance, the individual can begin to find their way through the labyrinth of the unconscious, to emerge transformed and renewed.

This idea of the dream as a labyrinth of transformation is beautifully expressed by Jungian analyst Clarissa Pinkola Estés, in her book Women Who Run With the Wolves. Estés describes the “enchanted forest” of the psyche, the wild and untamed landscape of the unconscious that women must learn to navigate in order to reclaim their instinctual wisdom and power.

Estés writes:

“The enchanted forest in the woman’s psyche is the place where all the lost and missing parts of herself reside. It is the place of intuition and instinct, of wild and natural impulses. It is the place where the shadows and the light coexist, where the cycles of birth and death, creation and destruction, are understood as part of the great mystery of life.”

For Estés, the enchanted forest is a labyrinth of the feminine unconscious, a realm of myths and fairy tales, dreams and visions. By entering into this labyrinth through the gateway of the dream, women can begin to reconnect with their wild and instinctual selves, to reclaim the parts of themselves that have been lost or suppressed by a culture that devalues the feminine.

Estés emphasizes the importance of storytelling and myth-making in this process of reclamation. By engaging with the archetypal stories and images of the collective unconscious, women can begin to map the labyrinth of their own psyches, to find the threads of meaning and purpose that guide them on their journey to wholeness.

This idea of the archetypal story as a map of the psyche is also central to the work of Jungian analyst Joseph Campbell. In his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell describes the “monomyth” of the hero’s journey – the universal pattern of separation, initiation, and return that underlies the myths and legends of cultures around the world.

For Campbell, the hero’s journey is a symbolic expression of the individuation process, the psyche’s quest for wholeness and self-realization. By following the labyrinthine path of the hero – descending into the underworld of the unconscious, confronting the shadows and monsters within, and emerging transformed with the treasure of the Self – the individual can begin to align themselves with the greater wisdom of the psyche, to find their place in the larger story of the cosmos.

Campbell writes:

“The labyrinth is thoroughly known; we have only to follow the thread of the hero path. And where we had thought to find an abomination, we shall find a god; where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves; where we had thought to travel outward, we shall come to the center of our own existence; where we had thought to be alone, we shall be with all the world.”

For Campbell, the labyrinth of the hero’s journey is not just an individual path, but a collective one as well – a way of connecting with the deeper mythopoetic structures of the human psyche, of finding our place in the greater web of stories and symbols that make up the collective unconscious. By engaging with these archetypal patterns through the gateway of dreams and active imagination, we can begin to navigate the labyrinth of the psyche with greater wisdom and clarity, to find the hidden treasures that await us at the center.

3.3. The Labyrinth and the Alchemical Opus

“Every life is complicated, every mind a kingdom of unmapped mysteries.”

– Dean Koontz

The labyrinth also figured prominently in Jung’s understanding of alchemy, the medieval precursor to depth psychology. In alchemical texts, the winding, recursive process of transmuting base metals into gold was often represented by labyrinthine patterns. Jung saw in these alchemical labyrinths an apt symbol for the psyche’s circuitous path to wholeness, with its cycles of dissolution and coagulation, its dances of opposites, its gradual refinement of the prima materia of the soul.

For Jung, alchemy was not simply a primitive form of chemistry, but a symbolic language for the individuation process – a way of mapping the psyche’s journey to wholeness through the metaphors of chemical transformation. In his extensive writings on alchemy, Jung explored the rich symbolism of the alchemical opus, seeing in its enigmatic images and operations a blueprint for the Self’s unfolding.

One of the central symbols of the alchemical process was the labyrinth, which represented the winding, recursive path of the opus. In alchemical illustrations, the labyrinth often appears as a circular, maze-like structure, with a series of concentric circles or spirals leading to a central point. This central point was seen as the goal of the opus – the philosopher’s stone, the elixir of life, the gold of the Self.

But reaching this center was no easy task. The alchemical labyrinth was a treacherous and disorienting place, full of false turns and dead ends, shadowy figures and deceptive illusions. To navigate this labyrinth, the alchemist had to surrender to the process, to allow themselves to be dissolved and reconstituted, broken down and rebuilt from the ground up.

This process of alchemical transformation was often represented by a series of color stages – nigredo (blackening), albedo (whitening), citrinitas (yellowing), and rubedo (reddening). Each of these stages corresponded to a different phase of the opus, a different level of purification and integration.

In the nigredo, the prima materia of the soul was plunged into darkness and chaos, stripped of its illusions and defenses. This was the stage of putrefaction and decay, the descent into the underworld of the psyche. In the albedo, the blackened matter was washed and purified, the impurities of the ego burned away in the fire of transformation. In the citrinitas, the purified matter was further refined and ennobled, the gold of the Self beginning to emerge from the dross of the unconscious. And in the rubedo, the final stage of the opus, the gold was fully realized, the Self shining forth in all its radiant wholeness.

For Jung, this alchemical process was a powerful metaphor for the individuation journey, the psyche’s labyrinthine path to wholeness. By surrendering to the opus, the individual could begin to integrate the split-off aspects of the psyche, to transform the lead of the shadow into the gold of the Self. This was not a linear or straightforward process, but a winding and recursive one, full of setbacks and reversals, breakthroughs and breakdowns.

In his book Psychology and Alchemy, Jung describes the alchemical labyrinth as a symbol of the “circumambulation” of the Self – the psyche’s gradual approach to wholeness through the integration of opposites. Jung writes:

“The alchemical operation consisted essentially in a series of transformations of the original material, the prima materia, into the final product, the lapis or philosopher’s stone. The transformations were brought about by means of a circular process, the so-called circulatio or circumambulatio. This ‘circular distillation’ is an apt symbol for the individuation process, whose goal is the synthesis of opposites.”

For Jung, the circulatio of the alchemical opus was a symbol of the Self’s inherent drive towards wholeness and integration. By engaging with the symbols and operations of alchemy, the individual could begin to align themselves with this natural process, to cooperate with the Self’s transformative power.

But Jung also recognized that this process was not without its dangers and challenges. The alchemical labyrinth was a place of great uncertainty and paradox, where the boundaries between self and other, inner and outer, often dissolved and shifted. To navigate this labyrinth required a great deal of courage and discernment, a willingness to confront the dark and irrational aspects of the psyche.

In his essay “The Psychology of the Transference,” Jung describes the alchemical labyrinth as a “sea of madness” that the adept must learn to navigate with skill and wisdom. Jung writes:

“The labyrinthine way is the via dolorosa of the alchemical process, leading through darkness and suffering to the light. The adept who sets out on this way must be prepared for ordeals and trials of every kind. He must have the courage to face the darkness within and without, to endure the confusion and paradox of the process.”

For Jung, the key to navigating the alchemical labyrinth was the transferential relationship between the adept and the prima materia – the raw material of the unconscious that the alchemist sought to transform. By entering into a dialogue with this inner “other,” the alchemist could begin to integrate the split-off aspects of the psyche, to bridge the gap between ego and Self.

This transferential relationship was often symbolized in alchemical texts by the coniunctio or “sacred marriage” between masculine and feminine principles. In the coniunctio, the alchemist and the prima materia were united in a state of wholeness and completion, the opposites of the psyche reconciled and integrated.

For Jung, this alchemical coniunctio was a powerful symbol of the individuation process, the psyche’s ultimate goal of unity and self-realization. By engaging with the symbols and operations of alchemy, the individual could begin to navigate the labyrinth of the unconscious with greater wisdom and clarity, to find the hidden treasure of the Self that awaited them at the center.

4 Labyrinth Work in Jungian Practice

“A labyrinth is a symbolic journey, but it is a map we can really walk on, blurring the difference between map and world.”

– Rebecca Solnit

4.1. Finger Labyrinths and Portable Designs

Jungian analysts and practitioners have developed various techniques for working with the labyrinth as a tool for self-exploration and therapeutic process. One common approach involves the use of finger labyrinths – small, portable designs that can be traced with the finger, enabling a meditative engagement with the twists and turns of the path. Such labyrinths can be used as a focus for concentration, a way of quieting the mind and attuning to the body’s wisdom.

Finger labyrinths come in a variety of materials and designs, from simple printed patterns to more elaborate wooden or metal structures. Some are small enough to fit in the palm of the hand, while others are larger and more intricate, requiring a slower and more focused tracing.

Regardless of the specific design, the basic principle of the finger labyrinth is the same: to provide a tangible, embodied way of engaging with the labyrinth symbol. By tracing the path with the finger, the individual can begin to internalize the rhythm and flow of the labyrinth, to align themselves with its winding, recursive structure.

This embodied engagement with the labyrinth can be particularly helpful for individuals who struggle with more abstract or conceptual forms of meditation or reflection. By giving the mind a concrete task to focus on – the tracing of the path – the finger labyrinth can help to quiet the chattering of the ego, to create a space of stillness and receptivity.

At the same time, the finger labyrinth can also serve as a powerful tool for self-exploration and insight. As the individual traces the path, they may find themselves confronting obstacles or challenges, moments of confusion or uncertainty. These experiences can be seen as mirrors of the psyche’s own twists and turns, the inner labyrinth of thoughts and emotions that the individual must navigate on the path to wholeness.

By staying present with these experiences, by allowing them to unfold without judgment or resistance, the individual can begin to gain a deeper understanding of their own psyche, to uncover the hidden patterns and dynamics that shape their inner world. The finger labyrinth becomes a kind of map or compass, guiding the individual through the labyrinth of the unconscious towards greater self-awareness and integration.

This process of self-exploration through the finger labyrinth is beautifully described by Jungian analyst Lauren Artress, in her book Walking a Sacred Path:

“The labyrinth is a mirror for the psyche. As we trace the path with our finger, we are tracing the path of our own journey, the twists and turns of our own life. The labyrinth invites us to surrender to the winding way, to trust the path even when it seems to be leading us away from our goal. It teaches us to embrace the mystery of the journey, to find meaning in the challenges and obstacles we encounter along the way.”

For Artress, the finger labyrinth is a powerful tool for cultivating this attitude of surrender and trust. By engaging with the labyrinth in a tactile, embodied way, we can begin to develop a felt sense of the psyche’s own wisdom, to align ourselves with the deeper currents of the unconscious that guide and shape our journey.

4.2. Guided Labyrinth Meditations and Active Imagination

“We all walk the long road. We’re all going to sleep in the cold dark. It’s how we walk that matters.”

– Barbara Brown Taylor

Another powerful technique for working with the labyrinth in Jungian practice is the guided labyrinth meditation. In this approach, the analyst leads the analysand through a visualization of the labyrinth journey, using verbal prompts and cues to evoke the twists and turns of the path.

The guided labyrinth meditation can be done with or without a physical labyrinth structure. In some cases, the analyst may have a large, walkable labyrinth available for the analysand to traverse while listening to the guided imagery. In other cases, the entire journey may take place in the imagination, with the analysand visualizing the labyrinth path in their mind’s eye.

Regardless of the specific format, the basic structure of the guided labyrinth meditation is the same. The analyst begins by inviting the analysand to relax and center themselves, to turn their attention inward and begin to cultivate a state of openness and receptivity. They may guide the analysand through some basic breath awareness or body scan exercises, helping them to arrive more fully in the present moment.

Once the analysand is settled and focused, the analyst begins to guide them into the labyrinth visualization. They may start by describing the entrance to the labyrinth, inviting the analysand to imagine themselves standing at the threshold, preparing to embark on the journey within.

As the analysand begins to walk the path in their imagination, the analyst guides them through the twists and turns of the labyrinth, using evocative language and imagery to bring the experience to life. They may describe the textures and colors of the path, the sensations of movement and flow, the shifting light and shadow as the analysand winds their way toward the center.

Along the way, the analyst may invite the analysand to pay attention to any thoughts, feelings, or images that arise, to allow these experiences to unfold without judgment or interpretation. They may offer gentle prompts or questions to help the analysand stay present with the journey, to deepen their engagement with the labyrinth experience.

As the analysand approaches the center of the labyrinth, the analyst may invite them to pause and rest for a moment, to allow themselves to be held in the stillness and silence of the center. This is a powerful moment of integration and insight, a chance for the analysand to connect with the deeper wisdom of the Self that lies at the heart of the labyrinth.

After a time of rest and reflection in the center, the analyst guides the analysand back out of the labyrinth, retracing the path they have just walked. This return journey is an opportunity for the analysand to integrate the insights and experiences of the center, to bring the wisdom of the labyrinth back out into their everyday life.

As the analysand emerges from the labyrinth visualization, the analyst helps them to ground and orient themselves, to return fully to the present moment. They may invite the analysand to share any insights or reflections that arose during the journey, to begin to process and integrate the experience.

The guided labyrinth meditation can be a powerful tool for deep self-exploration and transformation. By engaging the imagination and the senses in a structured, intentional way, the analysand can begin to access layers of the psyche that may be difficult to reach through more linear or analytical modes of inquiry.

At the same time, the guidance and support of the analyst can help to create a sense of safety and containment for the analysand, allowing them to venture into the depths of the unconscious with greater courage and resilience. The analyst becomes a kind of Ariadne, offering the thread of their presence and insight to guide the analysand through the labyrinth of the psyche.

This process of guided labyrinth work is beautifully described by Jungian analyst Jean Shinoda Bolen, in her book Crossing to Avalon:

“The labyrinth is a powerful tool for transformation, a crucible in which we can confront our shadows and claim our wholeness. As we walk the winding path, we are walking the path of our own soul’s journey, encountering the twists and turns of our own psyche. The presence of a skilled guide can help us to navigate this journey with greater clarity and compassion, to trust the wisdom of the labyrinth even when the way seems unclear.”

For Bolen, the guided labyrinth meditation is a way of accessing the deep, archetypal layers of the psyche, the mythic dimensions of the unconscious that shape our individual and collective journeys. By engaging with these archetypal energies in a conscious, intentional way, we can begin to align ourselves with the greater patterns of meaning and purpose that guide our lives.

4.3. Collaborative Labyrinth Drawings and Sandplay

“A labyrinth is an ancient device that compresses a journey into a small space, winds up a path like thread on a spool.” – Alix E. Harrow

In addition to finger labyrinths and guided meditations, Jungian practitioners also work with the labyrinth symbol in more creative and expressive ways. One powerful approach involves collaborative labyrinth drawings, in which analyst and analysand work together to create a visual representation of the labyrinth journey.

In this approach, the analyst and analysand begin with a large sheet of paper or canvas, and take turns adding elements to the labyrinth design. They may start with a basic template, such as the classical seven-circuit labyrinth pattern, and then embellish and elaborate on this structure as the drawing unfolds.

As they work on the drawing together, the analyst and analysand engage in a dialogue about the meanings and associations that arise. The analysand may choose to add particular images, colors, or symbols to the labyrinth, reflecting their own inner world and the themes of their journey. The analyst may offer observations or reflections, helping the analysand to explore the deeper significance of their choices.

Through this collaborative process, the labyrinth drawing becomes a kind of co-created map of the analysand’s psyche, a tangible representation of their unique journey towards wholeness and integration. The act of creating the drawing together also helps to strengthen the therapeutic alliance between analyst and analysand, fostering a sense of trust and shared exploration.

This approach to labyrinth work is beautifully described by Jungian analyst Sylvia Brinton Perera, in her essay “The Labyrinth: A Walking Meditation”:

“When analyst and analysand work on a labyrinth drawing together, they are co-creating a sacred space, a container for the analysand’s journey of self-discovery. The labyrinth becomes a mirror for the analysand’s inner world, reflecting back to them the themes and patterns of their own psyche. At the same time, the shared nature of the creative process helps to build a sense of connection and collaboration between analyst and analysand, supporting the analysand’s journey in a tangible and meaningful way.”

Another powerful way of working with the labyrinth symbol in Jungian practice is through sandplay therapy. In this approach, the analysand is invited to create a miniature labyrinth in a tray of sand, using a variety of small objects and figurines to represent different aspects of their inner world.

The analyst provides a range of materials for the analysand to choose from, including stones, shells, beads, and small figurines representing people, animals, and archetypal symbols. The analysand is then invited to create their labyrinth in the sand, arranging the objects in whatever way feels meaningful and resonant to them.

As with the collaborative drawing process, the creation of the sandplay labyrinth becomes a way for the analysand to externalize and explore their inner world in a tangible, embodied way. The three-dimensional nature of the sand tray allows for a greater sense of depth and dimensionality, reflecting the layered and complex nature of the psyche.

The analyst witnesses and supports the analysand’s process, offering observations and reflections as appropriate. They may also invite the analysand to engage in a dialogue with the different elements of the labyrinth, exploring the meanings and associations that arise.

Through this process of sandplay labyrinth work, the analysand can begin to access and integrate hidden or unconscious aspects of the psyche, bringing them into conscious awareness for healing and transformation. The labyrinth becomes a kind of sacred space, a container for the analysand’s inner journey.

This approach to labyrinth work is beautifully described by Jungian analyst Kay Bradway, in her book Sandplay: Silent Workshop of the Psyche:

“In the sandplay labyrinth, the analysand’s inner world takes visible form, reflecting back to them the deep themes and patterns of their psyche. As they arrange the objects in the sand, they are giving shape and expression to the unconscious, making the invisible visible. The labyrinth becomes a kind of alchemical vessel, a crucible for the transformation of the soul.”

Whether through finger labyrinths, guided meditations, collaborative drawings, or sandplay, the labyrinth symbol offers a rich and versatile tool for Jungian practitioners working with the unconscious. By engaging with the labyrinth in these embodied, expressive ways, analysands can begin to access and integrate the deeper layers of the psyche, navigating the twists and turns of their own unique journey towards wholeness and self-realization.

5. Jungian Thinkers and the Labyrinth

“The life of the creative man is lead, directed and controlled by boredom. Avoiding boredom is one of our most important purposes.”

– Saul Steinberg

5.1. Marie-Louise von Franz: The Labyrinth as Individuation Symbol

One of the most influential Jungian thinkers to explore the symbolism of the labyrinth was Marie-Louise von Franz, a close collaborator of Jung’s who made significant contributions to the development of analytical psychology. In her writings and lectures, von Franz often turned to the labyrinth as a powerful symbol of the individuation process, the psyche’s journey towards wholeness and self-realization.

In her book Archetypal Patterns in Fairy Tales, von Franz discusses the labyrinth as a recurrent motif in European fairy tales, often representing the hero’s quest for inner transformation. She notes that the labyrinth typically appears at a critical juncture in the hero’s journey, marking a descent into the unknown, a confrontation with the shadow, and an ultimate emergence into a new level of consciousness.

For von Franz, the labyrinth’s winding, circuitous path reflects the non-linear nature of the individuation process, the way in which growth and change often involve a doubling back, a retracing of one’s steps. She writes:

“The labyrinth…is one of the most important symbols of the individuation process. It expresses the idea that the way to the center is not direct, but winds in a puzzling, labyrinthine fashion. The nearer one gets to the center, the more complex and entwined the path becomes. This is an apt image for the process of individuation, which often feels like a confused wandering until one finds the hidden meaning in the difficulties encountered.”

Von Franz emphasizes that the goal of the labyrinth journey is not a straightforward attainment of some fixed endpoint, but rather a continual unfolding, a deepening of one’s relationship to the Self. The center of the labyrinth represents a state of wholeness and integration, but this is not a static achievement so much as an ongoing process of growth and self-discovery.

In her analysis of labyrinth symbolism in fairy tales, von Franz often focuses on the figure of the helpful animal or guide who appears to lead the hero through the maze. This figure can be seen as a personification of the Self, the inner wisdom that guides the ego on its journey of transformation.

For example, in the Grimms’ fairy tale “The White Snake,” the hero is guided through a labyrinth by a fox, who helps him to overcome various obstacles and ultimately win the hand of the princess. Von Franz interprets this fox as a symbol of the hero’s own instinctual wisdom, the inner guide that leads him through the labyrinth of the unconscious.

Similarly, in the Norwegian fairy tale “East of the Sun and West of the Moon,” the heroine is guided through a labyrinthine castle by a helpful white bear, who represents her own inner masculine principle. By following the bear’s guidance, the heroine is able to navigate the twists and turns of the labyrinth and ultimately free her lover from enchantment.

For von Franz, these helpful animals and guides reflect the supportive presence of the Self, the inner wisdom that guides the ego through the challenges of the individuation process. By attuning to this inner guidance, the individual can begin to navigate the labyrinth of the psyche with greater clarity and confidence.

At the same time, von Franz cautions against a simplistic or reductive approach to labyrinth symbolism. She emphasizes that the meaning of the labyrinth is always multivalent and context-dependent, reflecting the unique journey of each individual psyche.

In her essay “The Process of Individuation,” von Franz writes:

“The labyrinth…is a very profound symbol. It is not just a maze, a place where one gets lost, but it is a meaningful pattern. The labyrinth has a center, and the center is the goal of the journey. But the way to the center is not straight; it is a winding, spiraling path. This expresses the idea that the process of individuation is not a straight line, but a meandering, circular path.”

For von Franz, the labyrinth’s circular, winding nature reflects the cyclical, recursive nature of the individuation process. The journey towards wholeness is not a one-way street, but a continual process of descent and ascent, of moving into the depths of the unconscious and then integrating what one finds there into conscious awareness.

This process of integration is key to von Franz’s understanding of labyrinth symbolism. She emphasizes that the goal of the labyrinth journey is not simply to reach the center, but to bring the insights and energies found there back out into the world. The labyrinth is not an escape from reality, but a way of engaging with it more deeply and authentically.

In her book Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology, von Franz explores the labyrinth as a symbol of the alchemical process, the transformation of the psyche through the integration of opposites. She writes:

“The labyrinth…is a symbol of the alchemical opus. The alchemist must enter the labyrinth, the chaos of the prima materia, in order to find the gold, the philosophers’ stone. But this is not a one-way journey. The alchemist must also bring the gold back out of the labyrinth, and integrate it into his conscious life. The labyrinth is thus a symbol of the circular, spiraling nature of the individuation process, the endless interplay of conscious and unconscious.”

For von Franz, the alchemical labyrinth represents the paradoxical nature of the individuation journey, the way in which wholeness can only be attained through a willingness to embrace the unknown, to confront the shadow and the unconscious. By entering the labyrinth of the psyche, the individual sets in motion a process of transformation that ultimately leads back to the world, but with a new level of consciousness and integration.

Von Franz’s exploration of labyrinth symbolism thus offers a rich and nuanced perspective on the individuation process, one that emphasizes the non-linear, paradoxical nature of psychic growth. For von Franz, the labyrinth is not simply a symbol of confusion or disorientation, but a meaningful pattern that reflects the complex, spiraling journey of the Self. By engaging with this symbol in a deep and authentic way, the individual can begin to navigate the twists and turns of their own unique path towards wholeness and self-realization.

5.2. Lauren Artress: Walking the Sacred Path

Another influential figure in the contemporary Jungian engagement with labyrinth symbolism is Lauren Artress, an Episcopal priest and psychotherapist who has been a leading voice in the modern labyrinth revival. In her book Walking a Sacred Path: Rediscovering the Labyrinth as a Spiritual Practice, Artress explores the labyrinth as a powerful tool for personal and spiritual transformation, one that can help individuals to navigate the complexities of the modern world.

Artress first encountered the labyrinth in the early 1990s, when she was working as a canon pastor at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco. Inspired by the cathedral’s newly installed labyrinth, a replica of the famous medieval labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral in France, Artress began to explore the history and symbolism of this ancient pattern.

She was struck by the way in which the labyrinth seemed to offer a kind of antidote to the fragmentation and disconnection of modern life. In a world of constant distraction and over-stimulation, the labyrinth provided a space of stillness and centering, a way of reconnecting with the deeper rhythms of the soul.

For Artress, walking the labyrinth is a form of embodied prayer, a way of integrating mind, body, and spirit in a single, focused activity. She writes:

“Walking the labyrinth is a spiritual practice that integrates the body with the mind and the mind with the spirit. As we walk the labyrinth, we are walking a sacred path, a pilgrim’s way. We are walking the path of our own spiritual journey, the path of our own transformation.”

Artress emphasizes that the labyrinth is not a maze, a place of confusion and disorientation, but a unicursal path, a single winding route that leads inevitably to the center and back out again. This distinction is crucial for Artress, as it reflects the fundamental nature of the spiritual journey.

Unlike a maze, which is designed to confuse and disorient, the labyrinth has a clear and definite goal: the center, which represents the presence of the divine. The path to this center may be winding and circuitous, but it is not arbitrary or random. Every twist and turn has a purpose, every step brings the walker closer to the center, even when it may seem like they are moving away from it.

For Artress, this understanding of the labyrinth as a purposeful path is deeply resonant with the Jungian concept of individuation. Like the labyrinth, the individuation process is not a straight line from point A to point B, but a complex, spiraling journey that involves a constant interplay of conscious and unconscious, a repeated descent into the depths of the psyche and a re-emergence into the light of awareness.

Artress writes:

“The labyrinth is a powerful symbol of the individuation process. As we walk the labyrinth, we are walking the path of our own psychic development, the path of our own becoming. We are confronting the shadows and complexes that block our way, and we are discovering the hidden resources and potentials that lie within us.”

For Artress, walking the labyrinth is a way of engaging with this process in a conscious and intentional way. By setting aside time to walk the winding path, the individual creates a sacred space for self-reflection and self-discovery, a container in which the deep work of transformation can unfold.

Artress emphasizes that this work is not always easy or comfortable. Walking the labyrinth involves confronting the parts of ourselves that we may prefer to avoid or deny, the wounds and shadows that we carry within us. But it is precisely by engaging with these difficult places that we can begin to heal and transform them, to integrate them into a larger vision of wholeness.

In this sense, Artress sees the labyrinth as a kind of alchemical vessel, a crucible in which the prima materia of the psyche can be transformed into gold. By walking the labyrinth with intention and openness, the individual sets in motion a process of inner alchemy, a gradual transmutation of the lead of suffering into the gold of wisdom and compassion.

Artress also emphasizes the communal dimension of labyrinth walking, the way in which this practice can help to foster a sense of connection and solidarity among individuals. When we walk the labyrinth together, we create a shared space of intentionality and presence, a collective field of transformation.

In her work with labyrinth walking groups and workshops, Artress has witnessed the powerful effects of this communal practice. She writes:

“When we walk the labyrinth together, we create a container for each other’s journey. We become witnesses to each other’s process, supporting and encouraging each other along the way. We discover that we are not alone on this path, that we are part of a larger community of seekers, all walking the same winding road towards wholeness.”