In 1990, the Alabama State Legislature did something peculiar. With the stroke of Governor Guy Hunt’s pen, Act 90-203 declared Star Blue Quartz the official state gemstone. The legislation described it as “one of the most beautiful gemstones on earth, and the cheapest because there are so many.” There was just one problem: nobody seems to be able to find it.

Try searching for photographs of Alabama’s state gem online. You will discover something unsettling. Where Georgia can proudly display its quartz specimens and Arkansas its crystals, Alabama’s official gemstone exists primarily in the pages of legal code rather than in museum display cases or rockhound collections. The Alabama Department of Archives and History, the designated repository for the official specimen, reportedly holds a small, gray stone that bears little resemblance to the radiant gem the legislation promised.

As a therapist practicing in Alabama, I find this mystery irresistible. Not because I have any particular expertise in mineralogy, but because the Star Blue Quartz phenomenon illuminates something profound about how human beings construct meaning, maintain beliefs, and navigate the uncomfortable territory between what we want to be true and what actually is.

To understand this enigma fully, we must first descend into the geological reality of what Alabama’s earth actually contains. Only then can we appreciate the psychological dynamics at play when a community collectively believes in something the ground itself refuses to provide.

The Geological Framework

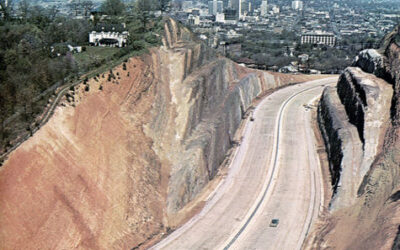

The Tectonic Architecture of Alabama

Alabama is not a monolithic geological entity. It is a mosaic of distinct physiographic provinces, each with a unique history written in stone over hundreds of millions of years. The formation of blue quartz, specifically the variety capable of displaying asterism (the star effect), requires a precise set of metamorphic or igneous conditions that are spatially restricted within the state. To understand whether Star Blue Quartz can exist here, we must understand what forces shaped this land.

The geological history of Alabama is dominated by the collision of continents. The Appalachian Mountains, which terminate in central Alabama, are the eroded remnants of a massive orogenic belt formed during the Paleozoic Era, when the ancient supercontinent Pangaea was assembling itself from smaller landmasses. The violence of that collision, the heat and pressure generated as continental plates ground against each other, created the conditions necessary to transform ordinary sediments into crystalline metamorphic rocks. It is within the roots of these ancient mountains that we must look for the genesis of true blue quartz.

The Alabama Piedmont, a subdivision of the Appalachian system, represents the most geologically complex region in the state. It is composed of metamorphic and igneous rocks that have been subjected to intense heat and pressure, the very conditions necessary to mobilize silica and incorporate the exotic inclusions required for blue coloration. The Piedmont divides into three major lithotectonic blocks, each with distinct characteristics: the Talladega Block, the Coosa Block, and the Tallapoosa Block.

The Talladega Block: The Metamorphic Fringe

The Talladega Block represents the frontal edge of the metamorphic belt, separated from the sedimentary foreland by the Talladega-Cartersville Fault System. The rocks here, including slates, phyllites, and the famous Sylacauga Marble, preserve primary sedimentary structures despite having been metamorphosed. This is significant because it tells us about the intensity of the transformation these rocks underwent.

The metamorphic grade of the Talladega Block (what geologists call greenschist facies) is generally too low to produce the high-temperature titanium or amphibole saturation required for blue quartz. The temperatures and pressures simply were not sufficient to create the necessary mineral assemblages. The quartz found here is typically massive, milky vein quartz, devoid of the inclusions necessary for color or asterism. You can find quartz in the Talladega Block, but it will not be blue, and it will not display a star.

The Coosa and Tallapoosa Blocks: The High-Grade Core

To the southeast of the Hollins Line Fault lies the high-grade metamorphic core of the Alabama Piedmont. This is the domain of the Ashland Supergroup and the Wedowee Group, formations composed of amphibolite-facies schists, gneisses, and amphibolites. Here, the temperatures and pressures during metamorphism were significantly higher, creating conditions more favorable for exotic mineral formation.

The presence of amphibolite is the critical geological clue. Amphibolites are metamorphic rocks composed largely of amphibole minerals such as hornblende, actinolite, and tremolite. In rare instances, localized chemical alteration (metasomatism) can produce alkali-rich amphiboles such as crocidolite or magnesioriebeckite. These minerals are naturally blue to blue-black in color.

The mechanism by which blue quartz could theoretically form in this region involves the intrusion of silica-rich fluids (quartz veins) into these amphibole-rich host rocks during peak metamorphism. As the quartz crystals grow, they can trap fibrous needles of the blue amphibole minerals. This is the only geologically viable mechanism for producing amphibole-included blue quartz in Alabama.

However, the geological record indicates that while amphibolites are common in the Wedowee and Ashland groups, the specific chemical environment required to create blue amphiboles (which demands high sodium and iron, low calcium) is extremely rare. Furthermore, the preservation of these fibers as distinct, oriented inclusions within large quartz crystals, rather than as a chaotic felted mass, is even rarer. The conditions must be precisely right, and they almost never are.

The Brevard Fault Zone

Separating the Northern Piedmont from the Inner Piedmont is the Brevard Fault Zone, a major crustal lineament characterized by intense cataclasis, the crushing and grinding of rock along the fault plane. The quartz found in the Brevard Zone is often mylonitic or phyllonitic, meaning it has been stretched and crushed into fine ribbons over millions of years of fault movement.

While this process can create interesting textures, it is destructive to the formation of large, single crystals required for gem-quality star stones. The blue quartz occasionally reported in cataclastic zones is often blue due to strain and micro-fractures that scatter light rather than due to mineral inclusions. More importantly, it rarely forms the single crystals needed for asterism. The fault zone that might seem like a promising geological feature actually works against the formation of the gemstone the legislature imagined.

The Hog Mountain Tonalite and the Gold Connection

Within the metamorphic fabric of the Piedmont lie younger igneous intrusions, most notably the Hog Mountain Tonalite in the Goldville District of Tallapoosa County. This area is historically significant as a gold-producing district, and the gold occurs in quartz veins that cut through the tonalite, a granitic rock rich in plagioclase feldspar.

Historical mining reports explicitly describe the quartz veins at Hog Mountain as “dark blue to black.” This sounds promising until we examine the cause of the coloration. Unlike the Star Blue Quartz of legislative imagination, the blue color at Hog Mountain is attributed to microscopic inclusions of sulfides (pyrite, pyrrhotite), graphite, or extremely fine-grained wall-rock contamination. This blue quartz is often opaque, fractured, and aesthetically somber. It is blue in a petrologic sense, a dark steely grey-blue, rather than in a gemological sense, a bright translucent azure. It does not typically exhibit asterism. While it is technically blue quartz found in Alabama, it fails to meet the visual expectations set by the term “state gemstone.”

The Cumberland Plateau: A Different Geological World

The geological investigation must now pivot to the northwest, to the Cumberland Plateau and the Highland Rim. This region includes Cullman, Madison, and Limestone counties, areas frequently cited in rockhounding forums as sources for the stone. Senator Don Hale, who sponsored the gemstone bill, represented Cullman County. This geographical fact becomes crucial to understanding the confusion at the heart of the Star Blue Quartz myth.

The Cumberland Plateau is underlain by Paleozoic sedimentary rocks. The dominant units are the Mississippian-aged Bangor Limestone, Tuscumbia Limestone, and Fort Payne Chert, capped by the Pennsylvanian Pottsville Formation. These are sedimentary layers, deposited in ancient shallow seas and deltaic environments over 300 million years ago.

The critical point is this: these rocks have never been subjected to the high-grade metamorphism found in the Piedmont. It is geologically impossible for metamorphic, amphibole-included blue quartz to form in situ in these sedimentary formations. The temperatures were never high enough. The pressures were never sufficient. The chemical environment was entirely wrong. Any crystalline quartz found here must be detrital, meaning pebbles eroded from the distant Appalachian mountains and transported by ancient rivers, then deposited among the sediments.

The Ubiquity of Chert

What does form in these sedimentary environments is chert. Chert is a sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline quartz (chalcedony), formed when silica precipitates from seawater or groundwater and accumulates in nodules or beds. The Fort Payne Chert formation is massive and widespread across northern Alabama, producing nodules and beds of chert ranging in color from white to grey to deep blue.

In the Tennessee Valley, particularly in Madison and Lauderdale counties, the chert is often a distinct blue-grey color, known locally as Blue Flint. This material was highly prized by indigenous peoples for toolmaking, and archaeological sites throughout the region contain artifacts fashioned from this attractive stone.

Here lies the source of the confusion. To an amateur collector, a water-worn pebble of translucent blue chert looks remarkably like a pebble of blue quartz. It has the same hardness (7 on the Mohs scale), the same conchoidal fracture pattern, and a similar density. The crucial difference is internal structure: chert is an aggregate of microscopic grains, while true quartz is a single crystal. This structural difference means chert cannot form a star in the traditional sense, because asterism requires oriented needle-like inclusions within a single crystal lattice, and chert has no single crystal lattice.

The Two-Stone Theory

The geological evidence points to a fundamental bifurcation in what people call “blue quartz” in Alabama. We are not dealing with a single mineral species but two distinct stones that share a color.

The first is Piedmont Blue Quartz: rare, metamorphic, macrocrystalline, potentially included with amphiboles, found in Clay, Cleburne, and Tallapoosa counties. This material exists but is uncommon, typically grey-blue rather than vivid blue, and rarely if ever displays true asterism.

The second is Plateau Blue Chert: abundant, sedimentary, microcrystalline, colored by trace impurities, found in Cullman, Madison, and Limestone counties. This material is common, can be quite attractive when polished, but is not quartz in the mineralogical sense and cannot produce a star.

The legislative designation of Star Blue Quartz appears to conflate these two materials. It takes the abundance and location of the chert (Cullman County, Senator Hale’s district) and applies the mineral name and optical property of the Piedmont quartz (star, blue). This geological mismatch is the primary driver of the myth status. Seekers look for Piedmont properties in Plateau geology and find nothing but chert. They are searching for something that cannot exist where they are looking.

The Physics of Blue and the Rarity of Stars

How Quartz Becomes Blue

To understand why photographs of this gemstone are so rare, we must examine the physics of how quartz turns blue. Unlike amethyst (colored by iron), citrine (also iron), or rose quartz (titanium and manganese), blue quartz is almost never colored by ionic substitution within the crystal lattice. It is a mechanical color, caused by physical inclusions rather than atomic-level chemistry.

The most famous blue quartz in the world, from localities like the Roseland District in Virginia or the Llano Uplift in Texas, is colored by Rayleigh scattering, sometimes called the Tyndall effect. When light enters the quartz crystal, it encounters microscopic inclusions, usually rutile (titanium dioxide) or ilmenite (iron titanium oxide), that are smaller than the wavelength of visible light, typically 0.1 to 0.3 micrometers in diameter. These particles scatter short-wavelength light (blue and violet) much more strongly than long-wavelength light (red and orange). This is the same physics that makes the sky blue.

The resulting color is milky or opalescent. It is not a crisp, transparent blue like sapphire. Crucially, if you look through such a stone at a light source (transmitted light), it appears yellowish-orange, because the blue light has been scattered out of the direct path. While Alabama’s Piedmont does contain rutile-bearing rocks, the intensity of saturation required to produce a vivid blue via scattering is not widely documented in the geological literature. The blue quartz of Alabama is more often described as grey-blue or dark blue, suggesting a different mechanism.

The second coloration mechanism, and the one most frequently cited in Alabama literature, is pigmentation by blue minerals, specifically fibrous amphiboles such as magnesioriebeckite or crocidolite (the asbestiform variety of riebeckite). These minerals are naturally dark blue to blue-black. When significant amounts of these fibers are trapped inside quartz during crystal growth, they impart a body color to the stone.

This type of blue quartz is typically opaque to translucent and has a steely or inky blue color. It lacks the internal glow of Rayleigh-scattered quartz. The fibrous inclusions can cause chatoyancy, the cat’s eye effect, if the fibers are aligned parallel to each other. Light reflecting off them produces a silky sheen or a distinct band of light. This fits the geological potential of the Wedowee Group schists in the Alabama Piedmont.

However, for the quartz to be star blue quartz, the fibers must be aligned in three directions, intersecting at 120 degrees. Amphibole fibers usually align in only one direction, parallel to the direction of crystal growth or the strain field during metamorphism. This produces a cat’s eye effect, not a star. The six-rayed star requires three sets of inclusions, each set parallel to one of the three crystallographic a-axes of the hexagonal quartz crystal. Getting amphibole fibers to arrange themselves this way is extraordinarily unlikely.

The blue chert of northern Alabama derives its color from entirely different variables. The blue coloration in chert is often due to disseminated phosphate minerals like vivianite, organic carbon from ancient marine organisms, or trace amounts of dispersed sulfide minerals. Because chert is microcrystalline, the color is usually uniform and matte. It does not transmit light well enough to show depth or internal stars. When blue chert is polished, it can take a high gloss. If the chert nodule contains concentric banding, common in sedimentary nodules, a polished dome might show a bullseye or sheen that an optimistic observer might interpret as a star. This is likely the source of many Star Blue Quartz claims from Cullman County.

The Crystallography of Asterism

The star component of the name Star Blue Quartz is the most mythical aspect of the designation. Asterism is a specific optical phenomenon that demands rigorous crystallographic compliance. It is not something that happens by accident or approximation.

For a six-rayed star to appear in quartz (a hexagonal mineral), several conditions must be met simultaneously. The crystal must be saturated with needle-like inclusions, usually rutile. These needles must exsolve, or precipitate, from the quartz lattice during cooling, and they must do so in an epitaxial relationship with the host crystal. Because of the hexagonal structure of quartz, the needles naturally align along the three crystallographic a-axes, intersecting at 60 degrees. This network of needles must be dense enough to reflect light but fine enough to allow light to enter the stone. Gemologists call this network silk. Finally, the lapidary must identify the c-axis (the optic axis) of the rough crystal and cut the cabochon perfectly perpendicular to it. Only then will the star appear, floating on the surface of the dome as the stone is rotated under a point light source.

Why is Alabama Star Blue Quartz geologically improbable? The inclusions that cause the blue color in Alabama, if they exist at all, are amphiboles rather than rutile. Amphiboles do not typically exsolve in a three-directional grid. They are usually captured as xenocrysts, foreign crystals, during vein formation, resulting in random or parallel orientation. You might get a dirty blue quartz. You might get a cat’s eye blue quartz if the fibers happen to align in one direction. But you will rarely if ever get a star blue quartz.

Furthermore, if the blue color comes from Rayleigh scattering by sub-micron particles, those particles are generally too small to act as specular reflectors for a star. A stone is usually either milky blue from the Tyndall effect or starry from macro-scale rutile needles. It is rare to find a stone that is both vividly blue and strongly asteriated. Compare this to star sapphires, which are blue due to iron and titanium charge transfer at the atomic level and starry due to rutile silk at the microscopic level. In star sapphire, the color and the star have different sources. In the hypothetical blue quartz, the color would be caused by the very inclusions that are supposed to create the star, and the physics simply does not work out.

Many collectors confuse girasol, a floating billowy light effect caused by light interference in quartz containing very fine inclusions, with asterism. Reports of Star Blue Quartz from Alabama are sometimes descriptions of girasol quartz, which does occur in the Piedmont. The effect is beautiful but it is not a star.

Some obscure reports mention a four-rayed star in Alabama quartz. This is crystallographically anomalous. A four-rayed star indicates a 90-degree intersection of inclusions, which is alien to the hexagonal (60-degree) symmetry of quartz. A four-rayed star in quartz usually implies the stone is actually a different mineral, like diopside, or that the quartz is pseudomorphing (replacing while maintaining the shape of) a cubic mineral. Alternatively, it may be a misidentification of two intersecting fracture planes reflecting light. The confusion is deepened by literature referencing localities in Virginia that produce four-rayed stars, suggesting that even the few verified reports may involve borrowed or misattributed data.

The Human Element

Act 90-203 and the Politics of Symbolism

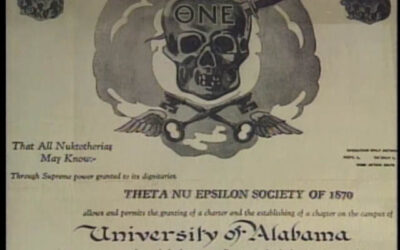

The persistence of the Star Blue Quartz myth is not due to geology. It is due to legislation. The legal code codified a rockhound’s enthusiasm into state dogma, and once codified, the myth became self-perpetuating.

On March 29, 1990, Governor Guy Hunt signed Act no. 90-203, designating Star Blue Quartz as the official gemstone of the State of Alabama. The bill was sponsored by Senator Don Hale of Cullman County. This geographical detail is crucial. As we have established, Cullman County is geologically incapable of producing metamorphic star quartz. It sits on the Cumberland Plateau, underlain by sedimentary rocks that have never experienced the conditions necessary for blue quartz formation. Cullman County is, however, rich in blue chert and flint.

The most plausible reconstruction of events is this: a local constituent found an attractive piece of blue chert, perhaps from the Flint River or a creek bed in Cullman County. The stone, tumbled smooth by water action, developed a surface that showed a chatoyant sheen when held to the light. The constituent, enthusiastic about the discovery, brought it to Senator Hale’s attention, perhaps describing it as blue quartz with a star. State legislatures rarely consult professional mineralogists for symbol bills. They function on civic pride and constituent enthusiasm. If a senator says his constituent found a rare blue gem, the legislature votes yes to honor the district.

The official description of the stone, stating that it is abundant and cheap, serves as the final betrayal of the legislative intent. If Star Blue Quartz were truly what the name implies, a rare asteriated gemstone, it would be expensive. Star sapphires command high prices precisely because the combination of color and asterism is uncommon. If the Alabama stone is abundant and cheap, it is almost certainly chert, not gem-quality quartz. The legislature unwittingly described the wrong stone while giving it the name of another.

The Missing Evidence

The Alabama Department of Archives and History is the designated repository for the official specimen of the state gemstone. Investigations by researchers reveal that the Archives does not have a prominent display of this gem. The specimen in their vault has been described as small and gray. The fact that the state archives cannot produce a photogenic, promotional image of the state gemstone, thirty-five years after its adoption, is perhaps the strongest evidence of its non-existence as a gem-quality resource.

The few images used on state websites and in promotional materials are often stock photos of blue quartz from other localities, particularly Virginia, or low-resolution images of greyish lumps that inspire no one. There is no Hope Diamond equivalent for Alabama, no stunning specimen that makes visitors gasp and reaches for their cameras. The absence speaks volumes.

The Rockhound’s Disappointment

For anyone asking why there are no photographs of this gemstone, the answer lies in the field experience of collectors who go looking for it. Rockhounding forums on Reddit, Mindat, and specialized websites are replete with posts from enthusiasts heading to the Flint River in Madison County to find the state gem. They invariably find blue flint, which is chert. They take the stones home, tumble them in polishing machines, and discover they have produced polished grey-blue rocks. The stones are opaque. They do not display stars. They are pleasant enough as river rocks but unremarkable as gemstones.

People rarely upload photographs of failed finds. Nobody posts a picture of a grey rock with the caption “Behold, the State Gem!” The lack of photographs online represents a form of survivor bias. Only beautiful stones get photographed and shared, and Alabama’s blue quartz is rarely beautiful in the way the name promises.

When photographs of attractive blue quartz do appear online with Alabama associations, they are frequently from Virginia. The Old Rag Granite of Virginia’s Blue Ridge produces well-documented blue quartz that is widely traded among collectors and lapidaries. Sellers on platforms like Etsy or eBay often list blue quartz without specific provenance. An Alabama buyer purchases the stone, assumes it represents the state gem, and posts a photograph. This creates a cycle of misinformation in which the only good photographs of supposed Alabama blue quartz are actually Virginia material.

If Star Blue Quartz were real and abundant, as the legislation claims, there would be a commercial market. Searches for Alabama Star Blue Quartz on lapidary supply websites yield almost no results for rough or cut stones. The results that do appear are often for synthetic blue star material or dyed quartz with no connection to Alabama. No major lapidary wholesalers sell Alabama rough. This absence of a supply chain confirms the geological scarcity.

Comparative Analysis

Comparing Alabama’s claimed gemstone to verified blue quartz localities around the world illuminates the anomaly. Virginia’s blue quartz from the Old Rag Granite is real, documented in geological bulletins, and readily photographable. The blue color comes from Rayleigh scattering by rutile inclusions, the material is translucent and opalescent, and while true asterism is rare, girasol effects are common. The stone is widely available at gem shows.

Texas produces Llanite from the Llano Uplift, a rhyolite porphyry containing blue quartz phenocrysts. The blue color comes from Rayleigh scattering by ilmenite inclusions. The material is opaque because it remains in its matrix rock, but it is real, documented, and photographable. Austrian blue quartz, colored by magnesioriebeckite inclusions, is rare but verified, translucent, and occasionally asteriated.

Alabama’s Star Blue Quartz stands alone in this comparison. It is defined by law rather than geology. The star property is the outlier that makes it suspicious. No other major blue quartz locality claims an abundance of star stones, because star stones are inherently rare regardless of locality. The legislation described something that the earth does not provide.

The Psychology of Belief

Symbolic Attachment and Regional Identity

Here is where the story becomes psychologically interesting. Symbols matter to human beings in ways that transcend their material existence. Research on national and regional identity consistently demonstrates that symbols serve as psychological anchors, creating feelings of belonging and continuity that fulfill deep emotional needs. The flag, the anthem, the state flower, the state gem: these are not merely decorative. They participate in what psychologists call identity-protective cognition.

When we invest in a symbol, we become motivated to maintain beliefs about it that preserve our sense of meaning. This is not delusion in any clinical sense. It is the ordinary operation of a mind designed to maintain coherent self-narratives and group affiliations. The desire for something to be true creates perceptual and memorial biases that shape how we encounter and retain information.

Ziva Kunda’s foundational work on motivated reasoning demonstrated that people do not simply believe whatever they wish. Rather, they engage in biased hypothesis testing, selectively attending to evidence that supports desired conclusions while subjecting contradictory evidence to heightened scrutiny. A person who wants the Star Blue Quartz to exist does not hallucinate specimens. Instead, they might interpret a chatoyant chert as showing asterism, remember the one encouraging anecdote while forgetting ten disappointing searches, or simply avoid investigating too closely.

The Therapeutic Parallel

In my clinical practice, I encounter versions of this phenomenon regularly. Clients hold beliefs about themselves, their relationships, or their circumstances that serve important psychological functions even when the evidence supporting them is thin. The belief that a distant partner will eventually commit. The conviction that a particular career path will finally bring fulfillment. The assumption that a geographic move will resolve internal distress. These are not psychotic delusions. They are normal human attempts to maintain hope and meaning in the face of uncertainty.

The question is never simply whether a belief is factually accurate. The question is what function the belief serves, what it costs to maintain, and what might become possible if it were examined more closely. A person searching creek beds for a gemstone that probably does not exist is not mentally ill. They are engaged in an activity that combines hope, identity, connection to place, and the simple pleasure of being outdoors looking for treasure. The belief animates meaningful behavior even if the specific object remains elusive.

Yet there is a shadow side. Motivated reasoning can trap us in patterns that prevent growth. The person who keeps investing in a relationship that offers only breadcrumbs, the entrepreneur who ignores mounting evidence against a business model, the seeker who spends decades pursuing a spiritual breakthrough that never arrives: at some point, the cost of maintaining the belief exceeds its benefits. The challenge lies in distinguishing between perseverance and denial, between faith and avoidance.

What Actually Exists

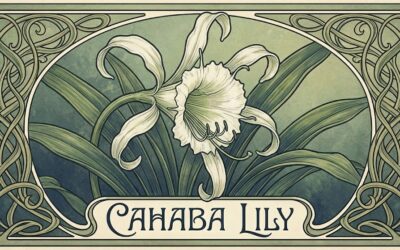

Perhaps the most therapeutic response to the Star Blue Quartz enigma is neither to debunk it entirely nor to pretend it is what the legislation claims. What actually exists in Alabama is this: the state contains blue stones. Some are chert, abundant in the north, historically significant to indigenous peoples, capable of taking a lovely polish. Some are genuine quartz from the Piedmont, steel-grey-blue, sometimes showing chatoyancy if not true asterism, genuinely rare and worth seeking. Neither matches the fantasy of a cheap, abundant, beautiful star gem. Both are real.

The mature position acknowledges loss while finding value in what remains. This is the psychological work of grieving illusions, a task that recurs throughout human life. We discover that a parent is not the omniscient protector we imagined. A career does not deliver the identity we expected. A relationship cannot fulfill the needs we projected onto it. And a state gemstone turns out to be more legislative enthusiasm than geological reality.

The goal is not cynicism but clarity. The blue stones of Alabama are worth appreciating for what they actually are. The Flint River chert connects us to deep time and indigenous history. The Piedmont quartz, rare as it is, offers genuine mineralogical interest. The legislative act itself tells a story about how communities construct shared symbols and the human need to mark our places as special.

Sitting With Ambiguity

Carl Jung wrote about the capacity to hold tension between opposites as a marker of psychological maturity. The Star Blue Quartz asks us to hold several truths simultaneously. The state has a legally designated gemstone. That gemstone, as described, probably does not exist in any meaningful quantity. Blue stones do exist and are worth seeking. The search itself has value regardless of what is found. The legislation reflects genuine civic pride even if it rests on mineralogical confusion.

This capacity for ambiguity is what differentiates rigid thinking from flexible wisdom. The rigid mind must resolve every contradiction, must declare the gemstone either real or fake, must debunk or defend. The flexible mind can appreciate the phenomenon in its full complexity, extracting meaning without requiring certainty.

In therapy, clients often want me to tell them definitively what to do. Should they leave the relationship? Take the job? Confront the family member? I generally resist these demands, not because I lack opinions, but because the work is in developing the capacity to sit with uncertainty, to gather information, to tolerate not knowing, and ultimately to make choices without guarantees. The Star Blue Quartz is a small koan, an invitation to practice this tolerance.

The Gift of Disappointment

There is something poignant about going to the Flint River expecting a gem and finding only flint. The disappointment is real. But disappointment, metabolized rather than avoided, is one of life’s great teachers. It forces contact with reality. It reveals the distance between expectation and actuality. It creates the conditions for more grounded engagement.

The rockhound who searches for years, finally concluding that the star blue quartz of legend does not exist in the expected form, has learned something valuable. Not just about geology, but about how desire shapes perception, how official pronouncements can mislead, and how meaning can be found in the search even when the object remains elusive. These are lessons that transfer far beyond creek beds.

In my own work with clients navigating loss, trauma, and the ordinary disappointments of existence, I have come to believe that the capacity to grieve lost illusions is among the most important psychological skills. It is not fun. Nobody enjoys discovering that what they believed was not so. But the alternative, maintaining increasingly elaborate defenses against reality, extracts a higher cost over time.

The Unicorn of Alabama

One geological analysis described the Star Blue Quartz as Alabama’s Unicorn, legally recognized but geologically elusive. I find this framing apt. Unicorns served important functions in medieval imagination even though no one ever captured one. They represented purity, wildness, the unattainable, the numinous. Their non-existence did not render them meaningless. It made them symbols.

Perhaps the Star Blue Quartz is best understood similarly. It represents something about Alabama’s self-conception, a desire to possess something rare and beautiful, to be special among states, to have a gemstone worthy of pride. That the geological reality does not quite match the legislative aspiration is less important than the impulse itself, which is deeply human.

If you wish to pursue this myth in the field, adjust your expectations accordingly. Abandon the hope of finding a star sapphire look-alike. Look instead for chatoyancy, a silky sheen that hints at oriented inclusions. Abandon the search for hexagonal crystal points. Look for water-worn river pebbles or massive vein chunks. Head to the Flint River in Madison County if you want abundant blue stones, understanding that what you find will be chert, beautiful in its own right but not what the legislature named. Head to the Goldville area in Tallapoosa County if you want a chance at genuine blue-grey quartz from hydrothermal veins, understanding that success is unlikely and the material will probably be steely rather than azure.

The lack of photographs online is an opportunity. The first person to upload a high-quality, verified image of Alabama blue quartz displaying even a hint of a star will effectively solve a thirty-five-year-old mystery. Until then, the search continues.

The next time you pass through Alabama, stop by a creek in the northern hills. Pick up a piece of blue chert. Hold it to the light. It will not produce a star. But it will connect you to millions of years of geological history, to indigenous peoples who shaped it into tools, to a contemporary legislature that wanted to honor their state, and to the endlessly fascinating ways that human beings make meaning from the materials of the earth.

That seems like enough. The search for certainty is often the enemy of appreciation. What we have, closely examined, may be more interesting than what we wished for. This is true of gemstones. It is true of relationships, careers, bodies, and lives. Learning to see and value what actually exists, rather than mourning the absence of what we imagined, is the work of a lifetime. Alabama’s elusive state gemstone offers an unexpected invitation to practice.

Bibliography

Official Law & State Gemstone Resources

-

Alabama Code § 1-2-26 (State Gemstone) – Justia Law

https://law.justia.com -

Alabama State Gemstone – NETSTATE

https://www.netstate.com -

Alabama State Gemstone – State Symbols USA

https://statesymbolsusa.org -

Alabama State Gemstone Info Dump – Reddit r/rockhounds

https://www.reddit.com/r/rockhounds

Geology, Piedmont Studies, USGS & Scholarly Work

-

Mineral Resources of the Northern Alabama Piedmont – SEGS

https://www.segs.org -

Tallassee Geolex Publications – USGS NGMDB

https://ngmdb.usgs.gov -

Structural Development of the Alabama Piedmont – American Journal of Science

https://ajsonline.org -

Geology of Milltown Alabama Quadrangle – Auburn ETD

https://etd.auburn.edu -

Gold Mining in Alabama – Russell Lands History

https://russelllandshistory.com -

Igneous-Rock Hosted Orogenic Gold Deposit (Hog Mountain) – Auburn ETD

https://etd.auburn.edu -

Quartz Textures & Mineralization at Hog Mountain – ResearchGate

https://www.researchgate.net -

Geology & Water Availability of Cullman County – USGS Publications Warehouse

https://pubs.usgs.gov -

Geologic Map: Hollywood 7.5-Minute Quadrangle – Geological Survey of Alabama

https://gsa.state.al.us

Lithic, Chert & Artifact Material Sites

-

Alabama Lithic Materials – Projectile Points

https://projectilepoints.net -

Gulf Coast Region Lithic Materials – Projectile Points

https://projectilepoints.net

Mineral Databases, Quartz Articles & Blue Quartz Resources

-

Blue Quartz (Mineral Info, Data, Localities) – Mindat

https://mindat.org -

Does Star Blue Quartz Exist? – Mindat

https://mindat.org -

Crocidolite – ClassicGems.net

https://classicgems.net -

Blue Quartz (Tucson 2016) – CSMS Geology Post

https://csmsgeologypost.blogspot.com -

Blue Chert (Tumbled Stones) – A Time for Karma

https://atimeforkarma.com -

Quartz from Henry County, Virginia – Mindat

https://mindat.org

Community Samples & Field Identifications (Reddit)

-

Some Blue Quartz from My Wife’s Farm – r/rockhounds

https://www.reddit.com/r/rockhounds -

Blue Quartz – r/rockhounds

https://www.reddit.com/r/rockhounds -

Found in Limestone Riprap, Central Alabama – r/rockhounds

https://www.reddit.com/r/rockhounds

Commercial Listings

-

Alabama Blue Star Quartz – Etsy

https://www.etsy.com

0 Comments