Why Understanding the Science of Consciousness Matters for Therapy

Before we dive into the life and work of one of the most important consciousness researchers alive today, we need to address a fundamental question. Why should therapists care about neuroscience? Why should someone seeking help for anxiety, depression, or trauma need to understand anything about how the brain generates conscious experience?

The answer cuts to the heart of what therapy actually is and what it can accomplish.

For most of the twentieth century, psychotherapy operated in a kind of theoretical fog. Clinicians developed techniques that seemed to work, but nobody could explain precisely why they worked. Freud speculated about psychic energy. Behaviorists focused on observable responses. Humanistic therapists emphasized the therapeutic relationship. Each school claimed success, but none could point to the biological mechanisms underlying that success.

This created a troubling situation. Without understanding the machinery of the mind, therapists were essentially working in the dark. They could observe that certain interventions helped certain people, but they could not predict which interventions would help which people or why some clients responded to treatment while others did not.

The emergence of cognitive neuroscience in the late twentieth century began to change this picture. Researchers developed tools that could peer inside the living brain and watch it process information in real time. Functional magnetic resonance imaging, electroencephalography, magnetoencephalography, and other technologies revealed the neural substrates of perception, memory, emotion, and thought.

But one mystery remained stubbornly resistant to scientific investigation. Consciousness itself. The felt quality of experience. The difference between processing information unconsciously and actually being aware of something.

This mattered enormously for therapy because so much of psychological suffering involves disorders of consciousness. Dissociation, where trauma survivors feel disconnected from their own experience. Flashbacks, where the past intrudes unbidden into present awareness. Rumination, where conscious attention becomes trapped in repetitive cycles of negative thought. Panic attacks, where the conscious mind is flooded with signals of danger it cannot control or understand.

If therapists could understand how the brain generates conscious experience, they might finally be able to understand why these disorders of consciousness occur and how to treat them more effectively.

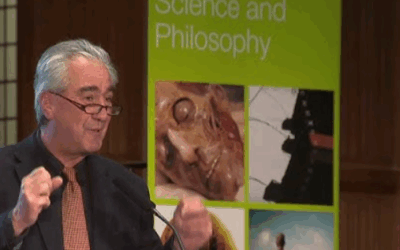

This is where Stanislas Dehaene enters the story. More than perhaps any other scientist alive today, Dehaene has cracked open the black box of consciousness and revealed the neural mechanisms inside. His work provides a scientific foundation for understanding not only how awareness arises from brain activity but also what happens when that process goes wrong.

For therapists working with trauma, dissociation, and other disorders of consciousness, Dehaene’s discoveries offer something revolutionary. They provide a map of the territory. They explain why certain therapeutic techniques work and others fail. They suggest new approaches that target the specific neural circuits involved in conscious access.

Understanding Dehaene’s work will not replace clinical skill or therapeutic presence. But it will deepen your understanding of what happens inside the minds you are trying to help. And that understanding can make all the difference.

The Early Years of a Mathematical Mind

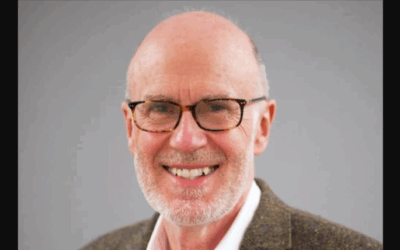

Stanislas Dehaene was born on May 12, 1965, in Roubaix, a medium-sized city in the north of France. By his own account, he had no early exposure to science and no idea what a scientific career might look like. But he was passionately curious about everything, a trait that would eventually lead him to one of the most ambitious research programs in modern neuroscience.

Dehaene’s first intellectual love was mathematics. He trained as a mathematician at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in Paris, one of France’s elite institutions for producing scholars and scientists. He obtained a master’s degree in applied mathematics and computer science from the University of Paris VI, fully expecting to pursue a career in pure mathematics.

But something happened that changed the trajectory of his life. He read a book.

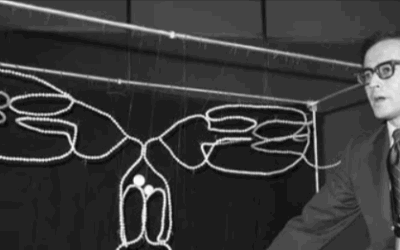

The book was L’Homme neuronal, published in 1983 by the French neurobiologist Jean-Pierre Changeux. The title translates as Neuronal Man, and the book argued that the human mind could be understood entirely in terms of the activity of neurons. Changeux proposed that mental states were brain states, that consciousness was a product of neural computation, and that the traditional mind-body problem could be dissolved by a sufficiently sophisticated understanding of neuroscience.

For Dehaene, this was a revelation. Here was a scientific program that combined the rigor of mathematics with the most profound questions about human nature. How does the brain produce the mind? What neural mechanisms underlie thought, language, and consciousness? These questions seized his imagination and never let go.

He abandoned his plans for a career in pure mathematics and began to retrain in cognitive psychology and neuroscience. In 1989, he completed his PhD in Experimental Psychology at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris, working with the cognitive scientist Jacques Mehler. But he also began a collaboration with Jean-Pierre Changeux himself, the author of the book that had inspired his transformation. This collaboration would prove extraordinarily fruitful and would eventually produce some of the most important theories in consciousness science.

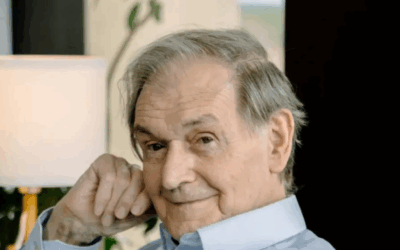

After completing his doctorate, Dehaene spent two years as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oregon, working with Michael Posner. Posner was one of the pioneers of human brain imaging and had developed influential theories of attention. The time in Oregon immersed Dehaene in the emerging techniques of cognitive neuroscience and gave him the skills to investigate the neural basis of mental processes.

He returned to France in 1997 to serve as Research Director at INSERM, the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research. In 2005, at the remarkably young age of 40, he was elected to the newly created Chair of Experimental Cognitive Psychology at the Collège de France, one of the most prestigious academic positions in the French-speaking world.

Today, Dehaene directs the INSERM-CEA Cognitive Neuroimaging Unit at NeuroSpin, France’s advanced brain imaging research center located in Saclay, south of Paris. He has received virtually every major award in neuroscience, including the Brain Prize in 2014, often described as the Nobel Prize of brain science, which he shared with Giacomo Rizzolatti and Trevor Robbins for their pioneering research on higher brain functions.

The Number Sense and the Reading Brain

Before turning to consciousness, Dehaene established himself as the world’s leading authority on two fundamental human cognitive abilities, our sense of number and our capacity for reading.

His research on numerical cognition revealed something remarkable. Humans possess an innate “number sense,” a primitive ability to perceive and manipulate approximate quantities that we share with other primates and even some birds. This ability is instantiated in a specific brain region, the intraparietal sulcus, which becomes active whenever we think about numbers.

Dehaene’s 1997 book The Number Sense synthesized this research for a general audience and won the Prix Jean-Rostand for best French-language general-audience scientific book. The work demonstrated that mathematical ability is not simply learned but builds on evolved neural circuits that were shaped by millions of years of natural selection.

His research on reading led to an equally striking discovery. When humans learn to read, a specific region of the left occipitotemporal cortex becomes specialized for recognizing written words. Dehaene called this the “visual word form area.” Before literacy, this region presumably serves other visual recognition functions. But when a child learns to read, it gets repurposed for processing written language.

This finding, detailed in his 2009 book Reading in the Brain, illustrates a principle Dehaene calls “neuronal recycling.” The brain’s circuits were not designed for reading, which is only a few thousand years old, far too recent for significant genetic evolution. Instead, reading hijacks circuits that evolved for other purposes and repurposes them for the new task of decoding written symbols.

Both lines of research established Dehaene’s credentials as a master of cognitive neuroscience. But they were also preparation for his most ambitious project, the scientific investigation of consciousness itself.

The Global Neuronal Workspace Theory

In the late 1990s, Dehaene turned his attention to what many considered the hardest problem in science. How does the brain generate conscious experience?

At the time, consciousness was still somewhat taboo in neuroscience circles. Many researchers considered it too subjective, too philosophical, too resistant to rigorous investigation. Experiments on consciousness were rare, and theories were mostly speculative.

Dehaene and his longtime collaborator Jean-Pierre Changeux decided to change that. Building on earlier work by the cognitive scientist Bernard Baars, they developed what has become known as the Global Neuronal Workspace Theory, or GNW.

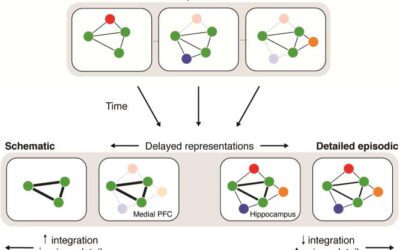

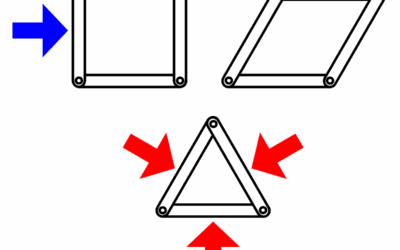

The theory begins with an observation about the brain’s architecture. The brain is organized into many specialized modules, each handling a specific type of information processing. One module processes color. Another handles motion. Another recognizes faces. Another parses the grammar of sentences. These modules work in parallel and largely unconsciously, like stagehands working behind the scenes in a theater.

But the brain also contains a system of long-distance connections linking the prefrontal cortex, the parietal cortex, and other regions. These connections form what Dehaene calls the “global workspace,” a kind of central information exchange where the outputs of different modules can be broadcast to the entire brain.

Here is the key insight. Consciousness, according to GNW theory, is what happens when information enters this global workspace and is broadcast widely across the brain. At any given moment, many modules are processing information unconsciously. But only one piece of information, perhaps a particular perception or thought, gains access to the workspace and becomes available to all the other systems simultaneously.

When this happens, Dehaene says the brain “ignites.” The term is literal. Neuroimaging studies show that conscious perception is associated with a sudden, dramatic increase in neural activity that spreads across distant brain regions. This ignition creates a temporary state of sustained, reverberating activity that makes the information available for verbal report, working memory, deliberate planning, and flexible response.

The metaphor Dehaene often uses is that of a theater. The stage of the theater is lit by a spotlight, which corresponds to attention. At any moment, many actors are backstage, preparing their performances in the dark. These correspond to the unconscious modules processing information outside of awareness. But when an actor steps into the spotlight, suddenly their performance is visible to the entire audience. The information has become conscious.

This theory makes specific, testable predictions. It predicts that conscious perception should be associated with late, sustained activity in the prefrontal and parietal cortices. It predicts that unconscious processing should show only early, transient activity that fails to trigger the global ignition. It predicts that consciousness should be “all or none,” with a sharp threshold separating conscious from unconscious states.

The Signatures of Consciousness

Over two decades, Dehaene and his team have conducted dozens of experiments testing these predictions. The results have been remarkably consistent with the theory.

One crucial finding involves the P300 wave, a characteristic electrical signal that can be detected on the scalp using electroencephalography. The P300 appears approximately 300 to 500 milliseconds after a stimulus is presented, but only when the subject consciously perceives that stimulus. If the stimulus is masked so that it remains unconscious, the early sensory responses in the brain are preserved, but the P300 vanishes.

This fits exactly with GNW’s prediction. Early sensory processing happens regardless of consciousness. But the P300, which reflects the ignition of the global workspace, requires conscious access.

Studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging tell a similar story. When subjects become consciously aware of a stimulus, there is a sudden increase in activation across a network of regions spanning the prefrontal and parietal cortices. This activation is accompanied by increased long-distance synchronization between these areas, as if distant populations of neurons suddenly begin singing from the same sheet of music.

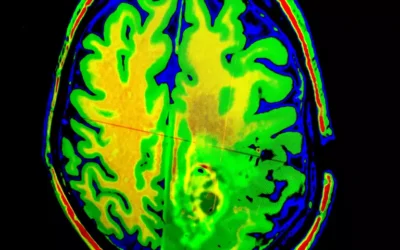

Perhaps most strikingly, studies of anesthesia and disorders of consciousness have shown that what distinguishes the conscious from the unconscious brain is precisely this capacity for global integration. When people lose consciousness under anesthesia, local neural processing often continues. The auditory cortex still responds to sounds. But the long-range connections that would normally carry information to the frontal lobes are disrupted. The global workspace fragments, and with it consciousness disappears.

Dehaene and his colleagues, working with neurologist Lionel Naccache at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, have developed practical applications of these findings. They created a test, sometimes called the “zap and zip” technique, that can measure the complexity of brain responses to magnetic stimulation. In conscious states, stimulation triggers a complex, spreading pattern of activity. In unconscious states, the response is simple and local. This test has proven valuable for assessing patients in comas or vegetative states, sometimes revealing preserved consciousness in individuals who cannot communicate.

The 2024 Adversarial Collaboration

In 2024, the field of consciousness science witnessed a landmark event. The Cogitate Consortium, funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, completed an adversarial collaboration directly testing the predictions of GNW against those of its main competitor, Giulio Tononi’s Integrated Information Theory.

The two theories make different predictions about where in the brain consciousness arises and how neural activity should be organized during conscious experience. GNW emphasizes the prefrontal cortex and the process of ignition. IIT emphasizes the posterior cortex and the degree of integrated information.

The study, published in Nature, involved 256 human participants who viewed visual stimuli while their brain activity was measured with multiple imaging techniques. Both theory proponents agreed in advance on the predictions and the criteria for evaluating success.

The results were nuanced. The study confirmed that the neural correlates of conscious content were primarily located in the posterior cortex, which favored IIT’s predictions about location. However, GNW was partially supported by evidence showing that the prefrontal cortex contained information about conscious content, though not in the sustained manner the theory predicted.

Critically, neither theory’s predictions were fully confirmed. The prefrontal activity predicted by GNW was more transient than expected, appearing at stimulus onset and offset but not maintaining a constant broadcast throughout the experience. The synchronization predicted by IIT was not reliably observed.

Dehaene and his colleagues responded by clarifying aspects of the theory and arguing that certain predictions had been misinterpreted. But the study represented exactly the kind of rigorous empirical testing that Dehaene himself had always advocated. The field was making progress by subjecting theories to careful experimental scrutiny.

What Dehaene’s Theory Teaches Us About Trauma

For clinicians working with trauma survivors, Dehaene’s work offers profound insights into the nature of traumatic experience and its treatment.

Consider first what happens during a traumatic event. The brain’s threat detection systems are activated. The amygdala sounds the alarm. The body mobilizes for fight, flight, or freeze. Under these conditions of extreme arousal, the normal processes of conscious perception and memory formation may be disrupted.

Dehaene’s research suggests that conscious experience requires the successful ignition of the global workspace. But during trauma, the overwhelming input from survival systems may prevent this ignition from occurring normally. Information may be processed by specialized modules, creating implicit memories encoded in the body and the sensory systems, without ever gaining access to the global workspace where it could be integrated with narrative memory and reflective awareness.

This provides a neurobiological explanation for many features of traumatic memory. Trauma survivors often have fragmented, sensory-dominated memories. They may experience vivid flashbacks, intrusive images, sounds, or bodily sensations, without being able to place these experiences in a coherent narrative context. The traumatic information was processed but never properly integrated into the global workspace.

It also helps explain dissociation. In dissociative states, the normal process of conscious integration is disrupted. Different aspects of experience may be processed in parallel but fail to ignite a unified conscious state. The person may feel detached from their body, as if watching themselves from outside, or experience the world as unreal. These are precisely the symptoms we would predict if the global workspace is fragmented or if information fails to broadcast properly across the brain.

From this perspective, effective trauma therapy must somehow help the brain reintegrate fragmented traumatic material. The goal is not just to “process” memories in some vague sense but to allow traumatic information to finally gain access to the global workspace where it can be consciously experienced, reflected upon, and integrated with the rest of the person’s life narrative.

This is exactly what many trauma therapies attempt to do. EMDR involves bringing traumatic memories to conscious awareness while simultaneously engaging the attentional system through bilateral stimulation. Brainspotting uses fixed eye positions to access and process subcortically stored material. Somatic Experiencing works with bodily sensations that may represent incompletely processed traumatic information.

What these approaches share, in the language of Dehaene’s theory, is that they help information that has been stuck in specialized modules finally ignite the global workspace. They create conditions where fragmentary sensory and somatic material can be consciously experienced, integrated with reflective awareness, and connected to narrative memory.

The timing dynamics of consciousness that Dehaene has mapped also have clinical implications. Conscious access requires a sequence of events unfolding over hundreds of milliseconds. The initial stimulus must be detected, then amplified, then broadcast. If this sequence is interrupted, whether by overwhelming input, attentional capture by threat, or dissociative disruption, consciousness may be incomplete or fragmented.

Trauma-informed therapy often involves working with very slow processing. Therapists help clients track minute changes in bodily sensation, staying present with emerging experience rather than being overwhelmed by it. From a GNW perspective, this slowing down may allow the ignition process to complete, giving fragmentary material time to broadcast across the workspace and integrate with reflective awareness.

The all-or-none quality of conscious access that Dehaene describes also has implications for treatment. There is a threshold for consciousness, below which information remains subliminal and above which it ignites into full awareness. Traumatic material often seems to hover just at or below this threshold, sometimes intruding into consciousness unbidden, other times remaining unavailable for retrieval.

Therapeutic techniques that carefully titrate exposure to traumatic material, increasing access gradually while maintaining nervous system regulation, may work by repeatedly bringing material closer to the ignition threshold without overwhelming the system. Over time, this may allow more and more of the traumatic information to successfully ignite and integrate.

Major Publications and Contributions

Stanislas Dehaene has authored over 400 scientific papers and several major books that have shaped our understanding of the mind and brain.

His 1997 book The Number Sense: How the Mind Creates Mathematics introduced the concept of an innate number sense to a general audience and established the field of numerical cognition. The book has been translated into numerous languages and won the Prix Jean-Rostand.

His 2009 book Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read explored the neural basis of reading and introduced the concept of neuronal recycling. The Washington Post named it one of the best science books of the year.

His 2014 book Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts synthesized two decades of research on the neural correlates of consciousness and presented the Global Neuronal Workspace Theory for general readers. The book won the Grand Prix RTL-Lire for best science book of the year and has been translated into fifteen languages.

His 2020 book How We Learn: Why Brains Learn Better Than Any Machine… for Now explored the science of learning and its implications for education. The French Society for Neurology named it book of the year.

His 2023 book Seeing the Mind: Spectacular Images from Neuroscience, and What They Reveal about Our Neuronal Selves presented dramatic visualizations of brain activity and what they reveal about human cognition.

Among his most influential scientific papers are the foundational theoretical work with Jean-Pierre Changeux establishing the Global Neuronal Workspace model, originally published in 1998 and subsequently elaborated in numerous papers. His empirical work on the signatures of consciousness, demonstrating the neural markers that distinguish conscious from unconscious processing, has been cited thousands of times and has shaped the field’s approach to investigating awareness.

A Timeline of Life and Work

1965 Born on May 12 in Roubaix, France

1983 Reads Jean-Pierre Changeux’s L’Homme neuronal, which transforms his career trajectory

1985 Completes master’s degree in Applied Mathematics and Computer Science at University of Paris VI

1989 Completes PhD in Experimental Psychology at École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales under Jacques Mehler; begins collaboration with Jean-Pierre Changeux

1989 Becomes research scientist at INSERM in the Cognitive Sciences and Psycholinguistics Laboratory

1992-1994 Postdoctoral fellowship at University of Oregon with Michael Posner

1997 Returns to France as Research Director at INSERM; publishes The Number Sense

1998 Publishes foundational paper on the Global Neuronal Workspace with Changeux

1999 Awarded James S. McDonnell Foundation Centennial Fellowship for work on the Cognitive Neuroscience of Numeracy

2001 Publishes edited volume The Cognitive Neuroscience of Consciousness

2003 Awarded Grand Prix scientifique de la Fondation Louis D. with Denis Le Bihan

2005 Elected to Chair of Experimental Cognitive Psychology at Collège de France; becomes director of INSERM-CEA Cognitive Neuroimaging Unit

2009 Publishes Reading in the Brain

2010 Elected to American Philosophical Society

2014 Awarded the Brain Prize with Giacomo Rizzolatti and Trevor Robbins; publishes Consciousness and the Brain

2018 Becomes president of the French Scientific Council for Education

2020 Publishes How We Learn; continues collaboration with Lionel Naccache on clinical applications

2023 Publishes Seeing the Mind

2024 Responds to results of Cogitate Consortium adversarial collaboration testing GNW predictions

Present Continues directing research at NeuroSpin and advising the French government on educational policy

The Continuing Quest

Stanislas Dehaene’s career represents one of the great scientific adventures of our time. He began with an abstract question, how does consciousness arise from the activity of neurons, and pursued it with mathematical rigor, experimental ingenuity, and theoretical ambition.

The Global Neuronal Workspace Theory he developed with Changeux and others provides a framework for understanding not just consciousness in general but the specific ways consciousness can be disrupted in clinical conditions. For therapists working with trauma, dissociation, and other disorders of awareness, this framework offers invaluable guidance.

We now know that consciousness requires the ignition of a global network, that this ignition has characteristic neural signatures, that it involves the broadcasting of information across distant brain regions, and that it can be disrupted by overwhelming input, attentional capture, or pathological processes. This knowledge does not replace the art of therapy, but it provides a scientific foundation that makes the art more effective.

Dehaene continues to push the boundaries of the field. He is exploring how spontaneous brain activity relates to conscious thought, how consciousness develops in infants, and how artificial systems might eventually achieve something like awareness. He is also working to translate neuroscience research into practical applications for education, helping teachers understand how the brain learns so they can teach more effectively.

For those of us interested in the healing of minds, Dehaene’s work is essential reading. It reminds us that the mysteries of consciousness, once considered beyond the reach of science, are yielding to careful investigation. And it suggests that as we understand more about how awareness arises from neural activity, we may finally understand how to help when that precious capacity is damaged or disrupted.

Want to learn more about how neuroscience informs trauma therapy? Contact GetTherapyBirmingham.com to explore brain-based approaches to healing.

Bibliography

Primary Sources by Stanislas Dehaene

Dehaene, S. (1997). The Number Sense: How the Mind Creates Mathematics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dehaene, S. (Ed.). (2001). The Cognitive Neuroscience of Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dehaene, S. (2009). Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read. New York: Penguin.

Dehaene, S. (2014). Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts. New York: Viking Adult.

Dehaene, S. (2020). How We Learn: Why Brains Learn Better Than Any Machine… for Now. New York: Viking.

Dehaene, S. (2023). Seeing the Mind: Spectacular Images from Neuroscience, and What They Reveal about Our Neuronal Selves. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Foundational Scientific Papers

Dehaene, S., & Changeux, J.P. (1998). A neuronal model of a global workspace in effortful cognitive tasks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(24), 14529-14534. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/

Dehaene, S., & Naccache, L. (2001). Towards a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness: Basic evidence and a workspace framework. Cognition, 79(1-2), 1-37. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/

Dehaene, S., Changeux, J.P., Naccache, L., Sackur, J., & Sergent, C. (2006). Conscious, preconscious, and subliminal processing: A testable taxonomy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(5), 204-211. Available at: https://www.cell.com/trends/cognitive-sciences/

Dehaene, S., & Changeux, J.P. (2011). Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing. Neuron, 70(2), 200-227. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21521609/

Mashour, G.A., Roelfsema, P., Changeux, J.P., & Dehaene, S. (2020). Conscious processing and the global neuronal workspace hypothesis. Neuron, 105(5), 776-798. Available at: https://www.cell.com/neuron/fulltext/S0896-6273(20)30052-0

The Cogitate Collaboration

Ferrante, O., et al. (2024). Adversarial testing of global neuronal workspace and integrated information theories of consciousness. Nature. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-08888-1

Naccache, L., Wang, X.J., Changeux, J.P., Sergent, C., Farisco, M., & Dehaene, S. (2025). GNW theoretical framework and the adversarial testing of global neuronal workspace and integrated information theories of consciousness. Neuroscience of Consciousness. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/nc/

Background on Global Workspace Theory

Baars, B.J. (1988). A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baars, B.J. (1997). In the theater of consciousness: Global workspace theory, a rigorous scientific theory of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 4(4), 292-309.

Dehaene, S., Changeux, J.P., & Naccache, L. (2011). The global neuronal workspace model of conscious access: From neuronal architectures to clinical applications. Research and Perspectives in Neurosciences, 55-84. Available at: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-18015-6_4

Trauma, Dissociation, and Consciousness

Frewen, P.A., & Lanius, R.A. (2015). Healing the Traumatized Self: Consciousness, Neuroscience, Treatment. New York: W.W. Norton.

Lanius, R.A., et al. (2015). Trauma-related dissociation and altered states of consciousness: A call for clinical, treatment, and neuroscience research. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, 27905. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4439425/

Lanius, R.A., et al. (2018). The dissociative subtype of PTSD. PTSD Research Quarterly, 29(3). Available at: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V29N3.pdf

Institutional Resources

Collège de France, Chair of Experimental Cognitive Psychology: https://www.college-de-france.fr/en/chair/stanislas-dehaene-experimental-cognitive-psychology-statutory-chair/biography

The Brain Prize, Stanislas Dehaene: https://brainprize.org/winners/higher-brain-functions-2014/stanislas-dehaene

Google Scholar Profile: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=2Dd5uoIAAAAJ

NeuroSpin Research Center: https://www.cea.fr/

Additional Research on Consciousness and Clinical Applications

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking.

Siegel, D.J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Porges, S.W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: W.W. Norton.

Cozolino, L. (2017). The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy: Healing the Social Brain (3rd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton.

0 Comments