How century-old transit decisions continue to shape where you drive, where you walk, and how you experience your neighborhood

If you’ve ever driven down Broadway Street in Homewood and wondered why it feels oddly wide for a two-lane road, or noticed that certain streets seem to cut at strange angles through otherwise orderly neighborhoods, you’re not imagining things. You’re experiencing the ghostly influence of infrastructure that vanished before most current residents were born.

The streets beneath your tires were laid out not for cars, but for streetcars. And the psychology of that century-old transit system continues to shape your daily movements in ways you’ve probably never consciously considered.

The Invisible Hand Beneath the Asphalt

In April 2018, road crews working on Broadway Street in Homewood made an unexpected discovery: buried beneath decades of asphalt lay the original brick roadbed and iron tracks of the Birmingham & Edgewood Electric Railway. The streetcar line had been paved over in 1968, forgotten by most residents. But the infrastructure had never really disappeared—it had simply become invisible, absorbed into the fabric of daily life.

This is a perfect metaphor for how our built environment shapes us. The streetcar stopped running before World War II, yet Broadway remains wider than most surrounding streets precisely because it was designed to accommodate those electric cars. Every time you drive that road, you’re following a path determined by transit planners in 1909.

The question is: what else in your daily routine was determined by people you’ve never met, solving problems that no longer exist?

A Brief History of Homewood’s Transportation DNA

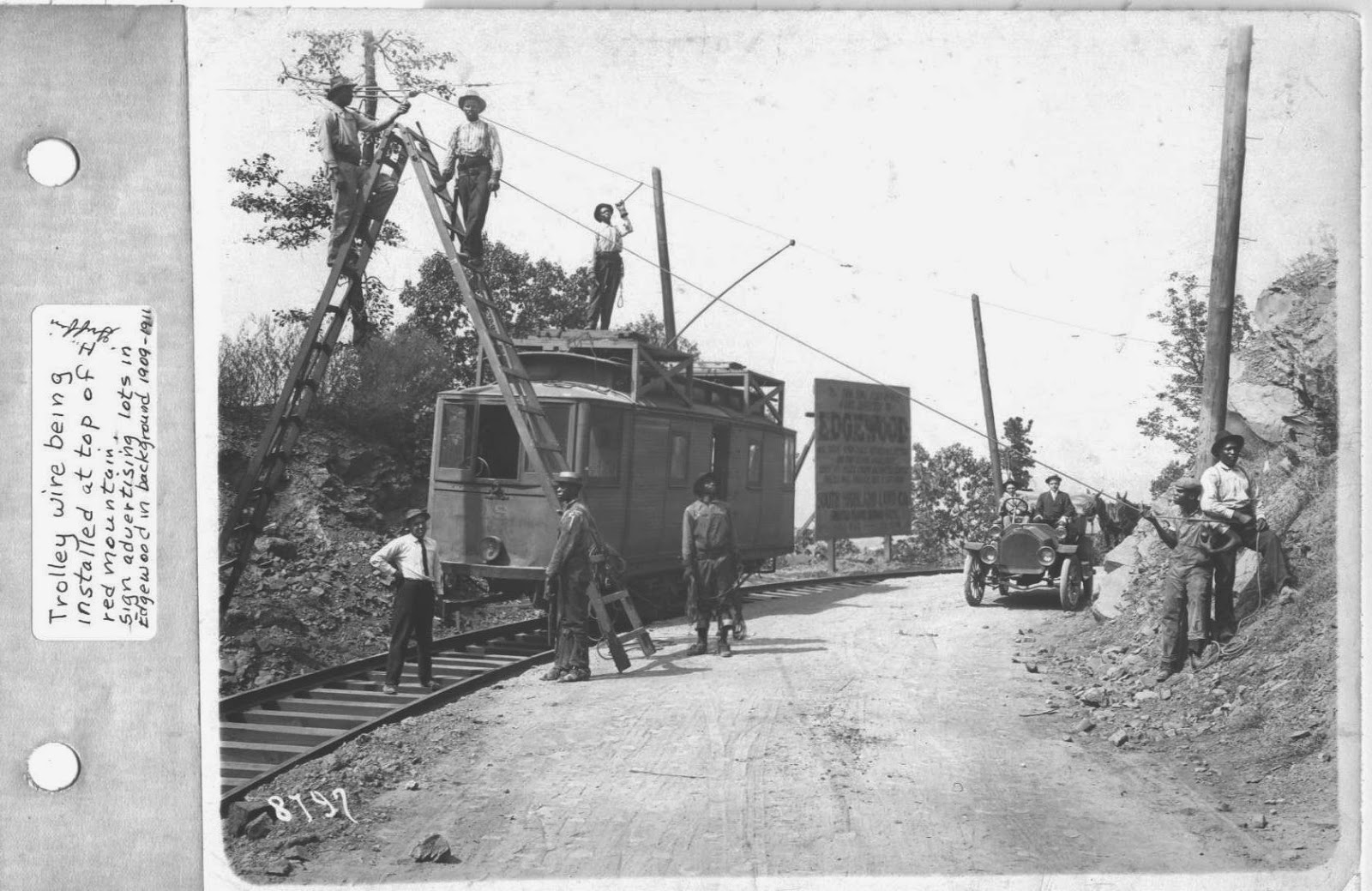

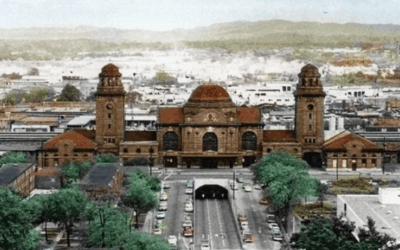

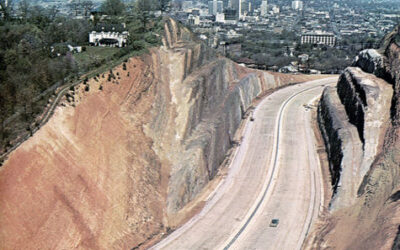

The Birmingham & Edgewood Electric Railway opened on July 1, 1911—a 5.4-mile line that extended streetcar service from downtown Birmingham over Red Mountain and into Shades Valley. The route was ambitious. Engineers determined that the grade up Red Mountain was too steep for streetcars, so they blasted a 72-foot deep cut through Lone Pine Gap, directly beneath where Vulcan stands today.

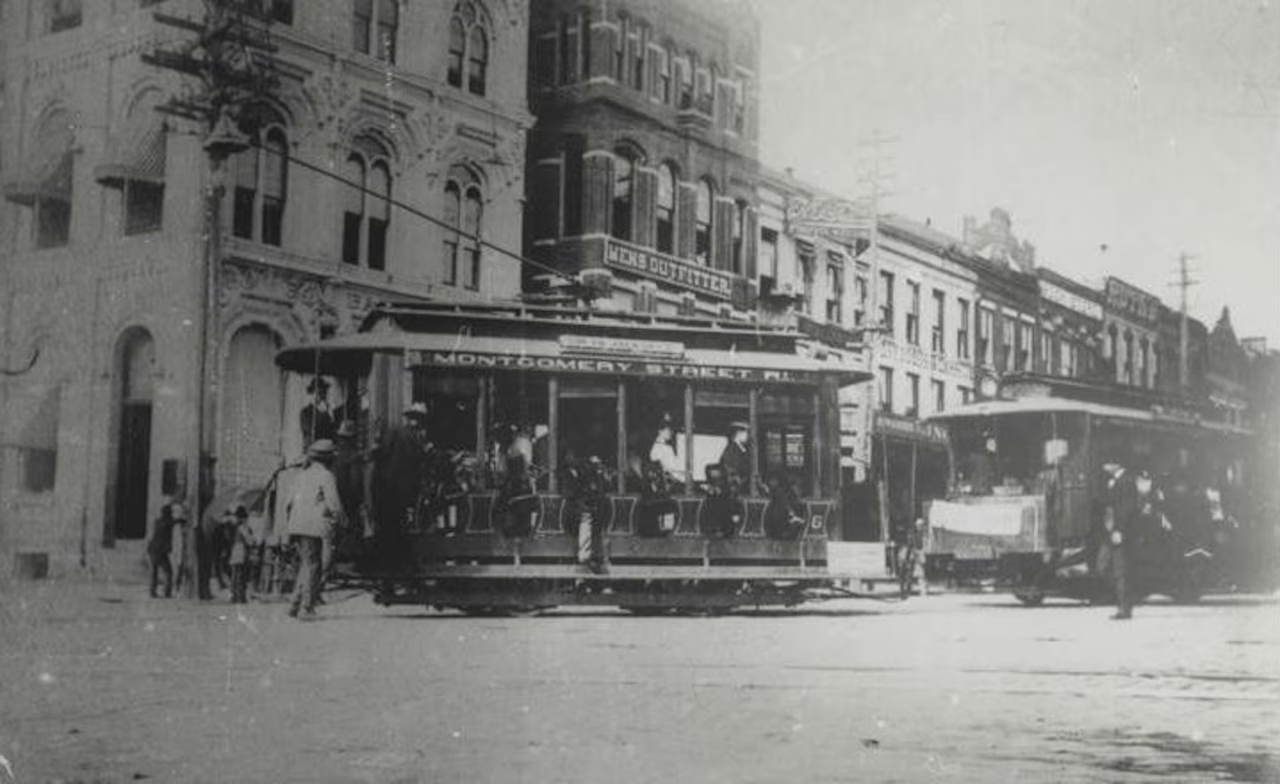

From there, the line descended into what would become Homewood, running down Central Avenue before turning onto 28th Court South, then continuing down Broadway Street until it reached its terminus at Edgewood Lake—an artificial lake created specifically as a destination for streetcar riders. If you’ve ever wondered why one of Homewood’s main arteries is called “Lakeshore Drive” when there’s no lake in sight, there’s your answer. The lake was drained decades ago, but the name persists.

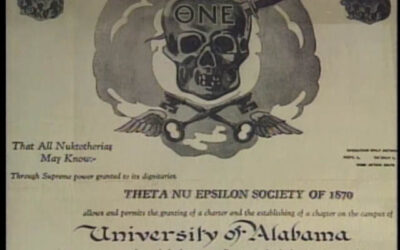

This wasn’t simply a transit project. It was a real estate venture. Stephen Smith and Troupe Brazelton formed the Edgewood Highlands Land Company and built the streetcar line specifically to increase the value of their land developments. They understood something that environmental psychologists would later quantify: transportation infrastructure doesn’t just move people—it shapes where they live, work, shop, and congregate.

By the time Edgewood, Rosedale, and Grove Park merged to form Homewood in 1926, the streetcar had already determined the community’s basic structure. Commercial corridors developed along the streetcar route. Residential neighborhoods grew in concentric rings around the stops. The grid of streets aligned to provide easy pedestrian access to the line.

The L&N Railroad’s Deeper Influence

But the streetcar was only the surface layer. Beneath it lay an even older and more consequential infrastructure: the Louisville & Nashville Railroad and its subsidiary, the Birmingham Mineral Railroad.

The L&N didn’t just pass through the Birmingham area—it essentially created it. As the railroad pushed into Alabama in the late 1800s, it encountered something extraordinary: one of the few places on Earth where coal, iron ore, and limestone—the three ingredients necessary for steel production—existed in close proximity. Birmingham was founded in 1871 at the crossing of two railroad lines. The L&N’s investment and transport capabilities helped transform a rural crossroads into the industrial powerhouse known as “The Magic City.”

The Birmingham Mineral Railroad eventually grew to include over 300 miles of track across seven central Alabama counties, serving mines and quarries that fed Birmingham’s hungry furnaces. One branch—the South and North Alabama Railroad—ran through what is now west Homewood, creating a junction near the present-day community.

When the streetcar line was built, it had to navigate around existing railroad infrastructure. At the crest of Red Mountain, the streetcar passed underneath the Birmingham Mineral Railroad before continuing south. The diagonal cuts and odd angles you notice in Homewood’s street grid often trace back to these negotiations between competing transportation systems, each following its own logic of topography and commerce.

Environmental Psychology and the Architecture of Choice

Here’s where it gets interesting from a psychological perspective.

Research in environmental psychology—the study of how physical surroundings affect behavior, emotions, and well-being—has consistently demonstrated that our built environment is not a neutral backdrop to our lives. It’s an active participant. The layout of streets, the position of buildings, the presence or absence of gathering spaces all influence how we move, who we encounter, and even how we think.

Streetcar suburbs like Homewood have what urban planners call “legibility”—their street patterns are comprehensible, their commercial areas are predictable, their boundaries are clear. This wasn’t an accident. The streetcar model required it. People needed to be able to walk to stops, so streets were laid out in grids. Commercial development clustered at intersections where pedestrian traffic concentrated. Residential areas filled in the spaces between.

Research has shown that people who live in areas with grid-like street patterns are more likely to use cardinal directions when navigating and report feeling more oriented in their environment. The clarity of the layout reduces cognitive load. You don’t have to think as hard about where you’re going.

Compare this to the curvilinear, cul-de-sac-dominated suburbs that proliferated after World War II, designed entirely around automobile access. These neighborhoods are often described by residents as disorienting—requiring GPS for basic navigation, isolating households from one another, creating what urbanists call “dendritic” patterns that force all traffic through a few arterial roads.

Homewood’s streetcar-era bones mean that when you drive down 18th Street or walk through downtown Edgewood, you’re moving through a built environment optimized for human-scale navigation. The streets were designed when most people walked to the streetcar, not when they drove to the highway. That legacy persists in the walkability scores, the pedestrian activity, the local business culture.

The Psychology of Inherited Infrastructure

But here’s the deeper psychological point, and the one most relevant to the work of psychotherapy:

Most of us are unaware of how thoroughly our daily movements are shaped by decisions made long before we were born, by people solving problems we never knew existed.

When you turn left at that intersection, when you choose one route over another, when you gravitate toward certain commercial districts and avoid others—you’re responding to an architecture of choice that was established by the Edgewood Highlands Land Company, the Birmingham & Edgewood Electric Railway, and ultimately the L&N Railroad. You experience these choices as your own preferences, your own habits, your own sense of what feels “right.”

This is not a trivial observation. One of the core insights of depth psychology is that much of what we experience as spontaneous choice is actually the expression of patterns laid down in the past. Just as Homewood’s streetcar tracks lie buried beneath modern asphalt, shaping traffic flow without anyone’s conscious awareness, our early experiences create neural pathways that continue to guide our behavior long after the original circumstances have changed.

The family you grew up in was your infrastructure. The relational patterns you learned—how to seek attention, how to manage conflict, how to experience intimacy or its absence—were your streets and railways. You navigate by them daily without ever consciously consulting a map.

What This Means for Understanding Yourself

Consider the slogan that developer Clyde Nelson used to market Hollywood Boulevard (now part of Homewood) in the 1920s: “Out of the Smoke Zone, Into the Ozone.” The phrase captured the appeal of escaping Birmingham’s industrial pollution for the cleaner air “over the mountain.”

That marketing slogan became the foundation for a regional identity. “Over the Mountain” remains shorthand for Birmingham’s suburban communities—places defined not by what they are, but by what they allowed people to escape from. An entire geography organized around avoidance.

How many of our life choices follow this same logic? Not movement toward something, but movement away? And how often do we mistake avoidance for preference, running from discomfort while believing we’re pursuing desire?

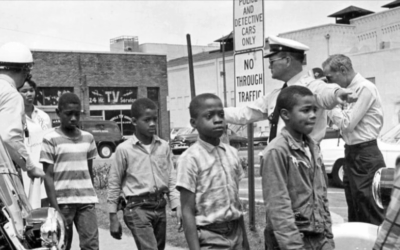

The streetcar suburbs were built to offer escape from crowded, polluted, disease-ridden urban cores. The 1873 cholera epidemic in Birmingham directly accelerated the development of what would become Homewood. People fled illness and found themselves in new communities, new patterns of living, new infrastructures that would shape generations to come.

We are not so different. Our psychological patterns often originate in moments of crisis—experiences we needed to survive, relationships we needed to escape, emotions we needed to avoid. The coping mechanisms we developed in those moments become the streets we drive every day, invisible and unquestioned.

The Work of Excavation

When Homewood road crews uncovered those streetcar tracks in 2018, they faced a choice: pave over the discovery and continue as if nothing had been found, or preserve a section of the tracks as a visible reminder of history.

They chose preservation. A small section of Broadway now displays the original bricks and iron rails, a physical acknowledgment that what lies beneath shapes what exists above.

This is not unlike the work of psychotherapy. We excavate. We examine the infrastructure beneath the surface—the patterns, the assumptions, the buried experiences that continue to determine our routes through life. Some of what we find can be simply noted and honored, like those preserved streetcar tracks. Other discoveries demand more active work: rerouting, rebuilding, sometimes tearing up pavement that no longer serves us.

The streets of Homewood weren’t inevitable. They were designed by specific people making specific choices based on the technology, economics, and values of their time. Many of those choices were wise; some were shortsighted; all of them were contingent. Things could have been different.

The same is true for the psychological infrastructure we carry. The patterns we learned were responses to specific circumstances. They made sense in context. But contexts change, and sometimes the routes that once kept us safe now lead us in circles.

The first step is simply noticing—recognizing that the street you’ve driven a thousand times follows a path carved by a streetcar that stopped running eighty years ago. Recognizing that your response to conflict, your approach to intimacy, your relationship with your own emotions all flow along channels cut by experiences that may no longer apply.

From there, choice becomes possible.

Joel is a Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker and the Clinical Director of Taproot Therapy Collective in Hoover, Alabama. The practice specializes in brain-based approaches to complex and treatment-resistant trauma, offering modalities including somatic experiencing, brainspotting, and neuromodulation. If you’re interested in exploring the hidden infrastructure of your own psychological patterns, you can learn more at gettherapybirmingham.com.

Sources: Birmingham & Edgewood Electric Railway historical records via BhamWiki; Louisville & Nashville Railroad history via the L&N Historical Society and Encyclopedia of Alabama; Homewood city history via the City of Homewood and Encyclopedia of Alabama; environmental psychology research on urban planning and behavior from Frontiers in Psychology and the Journal of Environmental Psychology.

0 Comments