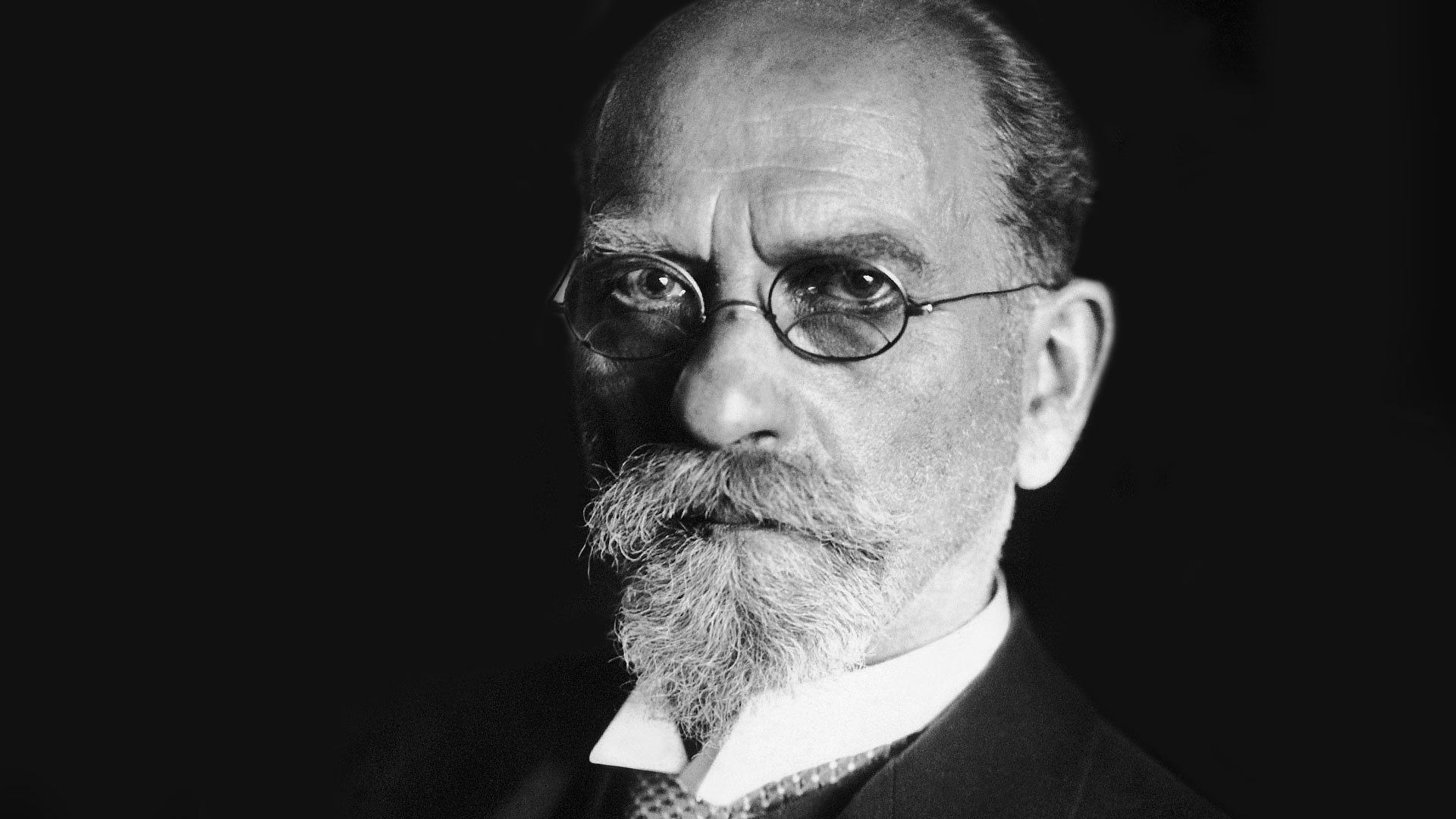

Who was Edmund Husserl?

Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), the German philosopher widely regarded as the founder of phenomenology, has had a profound and enduring influence on the development of psychology and psychotherapy. His rigorous investigation of the structures of consciousness and his call for a return “to the things themselves” have inspired generations of thinkers to explore the lived experience of the human mind. In this essay, we will examine Husserl’s key philosophical contributions, trace their impact on various schools of psychological thought, and consider their ongoing relevance for the theory and practice of psychotherapy.

The Phenomenological Method and the Study of Consciousness

At the heart of Husserl’s philosophy is the phenomenological method, a systematic approach to the study of consciousness that seeks to describe the essential features of experience as they appear to the subject. Husserl argued that in order to establish a truly scientific psychology, researchers must set aside their preconceptions and theoretical assumptions and attend carefully to the phenomena of mental life as they present themselves.

This methodological innovation laid the groundwork for a new way of investigating the mind, one that prioritized the first-person perspective and sought to elucidate the inherent meaningfulness of human experience. By suspending the “natural attitude” and engaging in a process of “phenomenological reduction,” Husserl believed that psychologists could uncover the invariant structures of consciousness and shed light on the constitutive role of subjectivity in shaping our understanding of the world.

Intentionality and the Philosophy of Mind

Central to Husserl’s phenomenology is the concept of intentionality, the idea that consciousness is always consciousness of something. Husserl argued that the mind is not a passive receptacle for sensory impressions, but an active, meaning-bestowing power that is always directed towards objects and states of affairs.

This insight challenged the prevailing assumptions of both empiricist and rationalist approaches to the mind and paved the way for a more dynamic and context-sensitive understanding of mental life. Husserl’s analysis of the intentional structure of consciousness has had a profound impact on the philosophy of mind and has inspired a wide range of psychological theories that emphasize the active, interpretive nature of human experience.

The Lifeworld and the Crisis of European Sciences

In his later work, Husserl became increasingly concerned with the crisis of meaning and rationality in European culture, which he saw as a consequence of the dominance of naturalistic and objectivistic modes of thought. He argued that the scientific worldview had become detached from the pre-theoretical, experiential basis of human life and had lost sight of the essential role of subjectivity in constituting the world.

To address this crisis, Husserl introduced the concept of the lifeworld (Lebenswelt), the pre-given, intersubjective horizon of meaning that underlies all human experience and activity. He called for a renewed attention to this lifeworld and a reintegration of scientific knowledge into the context of everyday life.

This critique of the dehumanizing tendencies of modern science and technology has had a significant impact on the development of humanistic and existential approaches to psychology, which seek to situate the study of the mind within the broader context of human existence and to recognize the irreducible complexity and richness of lived experience.

Husserl and the Foundations of Phenomenological Psychology

Husserl’s philosophical work laid the foundation for the emergence of phenomenological psychology, a broad movement that sought to apply the insights and methods of phenomenology to the study of human experience and behavior. While Husserl himself did not develop a systematic psychological theory, his ideas have been taken up and elaborated by a wide range of thinkers who have sought to build a more experientially grounded and meaning-centered approach to the science of the mind.

One of the most influential figures in this tradition was Martin Heidegger, Husserl’s student and colleague, who developed a hermeneutic phenomenology that emphasized the ontological dimensions of human existence. Heidegger’s analysis of being-in-the-world and his exploration of the existential structures of care, anxiety, and authenticity have had a profound impact on the development of existential psychotherapy and have inspired a wide range of philosophical and psychological investigations into the nature of human being.

Another key figure in the phenomenological tradition was Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose work on embodiment, perception, and intersubjectivity has been particularly influential in the fields of developmental psychology, cognitive science, and psychotherapy. Merleau-Ponty’s emphasis on the lived body as the primary site of meaning and his exploration of the pre-reflective dimensions of experience have challenged the mind-body dualism that has long dominated Western thought and have opened up new avenues for understanding the complex interplay between the biological, psychological, and social dimensions of human life.

The Influence of Husserl on Humanistic and Existential Psychology

Husserl’s phenomenological approach has been particularly influential in the development of humanistic and existential schools of psychology, which emerged in the mid-20th century as a response to the perceived limitations of psychoanalytic and behaviorist theories. These approaches share a common emphasis on the inherent meaningfulness of human experience, the centrality of values and choice in shaping the course of individual lives, and the importance of understanding the person in context.

The humanistic psychology of Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, for example, drew heavily on Husserl’s insights into the intentional structure of consciousness and the primacy of subjective experience. Rogers’ person-centered therapy, which emphasizes the importance of empathy, unconditional positive regard, and congruence in the therapeutic relationship, can be seen as a practical application of Husserl’s call for a return to the lifeworld and a recognition of the constitutive role of intersubjectivity in shaping human experience.

Similarly, the existential psychotherapy of Rollo May and Irvin Yalom owes much to Husserl’s analysis of the structures of human existence and his emphasis on the inescapable realities of freedom, finitude, and responsibility. May’s exploration of the creative dimensions of anxiety and Yalom’s investigation of the ultimate concerns of death, isolation, meaninglessness, and freedom can be seen as elaborations of Husserl’s phenomenological insights into the fundamental structures of human experience.

Husserl and the Cognitive Revolution in Psychology

While Husserl’s influence has been most pronounced in the humanistic and existential traditions, his ideas have also had a significant impact on the development of cognitive psychology and the broader cognitive sciences. Husserl’s analysis of the intentional structure of consciousness and his emphasis on the active, meaning-bestowing power of the mind anticipated many of the key insights of the cognitive revolution of the 1950s and 60s.

Husserl’s phenomenology can be seen as a precursor to the constructivist and enactive approaches to cognition that have gained prominence in recent decades. These approaches challenge the traditional view of the mind as a passive processor of information and instead emphasize the active, interpretive nature of human experience and the complex interplay between perception, action, and meaning-making.

Husserl’s emphasis on the lifeworld and the pre-theoretical dimensions of experience has also inspired a growing interest in the embodied, embedded, and extended nature of cognition. This perspective recognizes that mental processes are deeply rooted in bodily experience, shaped by social and cultural contexts, and extended through technological and linguistic scaffolding.

Phenomenology and the Future of Psychotherapy

As the field of psychotherapy continues to evolve and diversify, Husserl’s phenomenological approach offers a rich and generative framework for understanding the complexities of human experience and the challenges of facilitating growth and change. By attending carefully to the lived experience of the client and recognizing the constitutive role of meaning and intersubjectivity in shaping mental life, therapists can develop a more nuanced and context-sensitive approach to their work.

Husserl’s emphasis on the lifeworld and the pre-reflective dimensions of experience also has important implications for the practice of psychotherapy. By helping clients to reconnect with the experiential basis of their lives and to cultivate a more embodied and integrated sense of self, therapists can facilitate a process of personal transformation that goes beyond the mere alleviation of symptoms and aims at a more authentic and fulfilling way of being in the world.

At the same time, Husserl’s critique of the dehumanizing tendencies of modern science and technology serves as a important reminder of the ethical and existential dimensions of psychotherapy. As the field becomes increasingly shaped by the discourses of neuroscience, genetics, and digital technology, it is essential that therapists remain grounded in the lived experience of their clients and committed to the values of empathy, compassion, and respect for the irreducible complexity of human existence.

Edmund Husserl’s phenomenological philosophy has left an indelible mark on the development of psychology and psychotherapy. His rigorous investigation of the structures of consciousness, his emphasis on the intentional nature of mental life, and his call for a return to the lifeworld have inspired generations of thinkers to explore the richness and complexity of human experience.

Selected References:

Bernet, R., Kern, I., & Marbach, E. (1993). An introduction to Husserlian phenomenology. Northwestern University Press.

Carr, D. (1999). The paradox of subjectivity: The self in the transcendental tradition. Oxford University Press.

Crowell, S. (2001). Husserl, Heidegger, and the space of meaning: Paths toward transcendental phenomenology. Northwestern University Press.

Gallagher, S., & Zahavi, D. (2008). The phenomenological mind. Routledge.

Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy. Northwestern University Press.

Husserl, E. (1983). Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to a phenomenological philosophy. First book: General introduction to a pure phenomenology (F. Kersten, Trans.). Martinus Nijhoff.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception (C. Smith, Trans.). Routledge.

Mohanty, J. N. (1995). The possibility of transcendental philosophy. Kluwer Academic.

Moran, D. (2000). Introduction to phenomenology. Routledge.

Sartre, J.-P. (1956). Being and nothingness: A phenomenological essay on ontology (H. E. Barnes, Trans.). Washington Square Press.

Spiegelberg, H. (1994). The phenomenological movement: A historical introduction. Kluwer Academic.

Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Harvard University Press.

Van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Routledge.

Zahavi, D. (2003). Husserl’s phenomenology. Stanford University Press.

Philosophy

0 Comments