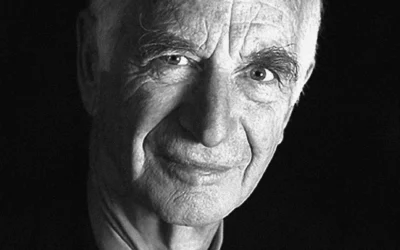

Albert Bandura transformed our understanding of how human beings learn and change. While earlier behaviorists had focused on direct experience as the engine of learning, Bandura demonstrated that we can acquire new behaviors, attitudes, and emotional responses simply by watching others. This insight, which seems obvious in retrospect, challenged fundamental assumptions of behavioral psychology and opened entirely new avenues for therapeutic intervention. But Bandura’s contributions extended far beyond observational learning. His theory of self-efficacy, the beliefs we hold about our capacity to succeed, has become one of the most influential concepts in psychology, with applications ranging from education to health behavior to psychotherapy.

Bandura was born on December 4, 1925, in Mundare, a small town in Alberta, Canada, about fifty miles east of Edmonton. The town had been settled largely by Eastern European immigrants, and Bandura’s parents were among them. His father, Joseph Bandura, had emigrated from Poland, while his mother, Justina Bandura, came from Ukraine. Both worked hard to establish themselves in their new country, his father as a farmer and his mother operating a local business. The family was not wealthy, but they valued education and encouraged their children’s intellectual development.

Mundare was a small community with limited educational resources. The local high school had only two teachers and offered a narrow curriculum. Yet Bandura has credited this environment with fostering his independence and self-direction. When the school did not offer courses he wanted to take, he organized study groups with other students to teach themselves. This early experience of self-directed learning may have planted seeds for his later theoretical interest in human agency and self-regulation.

After graduating from high school, Bandura attended the University of British Columbia, initially with the intention of pursuing a career in one of the biological sciences. His path to psychology was somewhat accidental. Needing to fill a time slot in his course schedule, he enrolled in an introductory psychology course that happened to meet at a convenient hour. The subject captured his interest, and he ended up majoring in psychology, graduating in 1949 with the Bolocan Award in psychology, the department’s highest honor for undergraduate students.

Bandura then moved to the United States for graduate study at the University of Iowa, which had one of the strongest psychology programs in the country. Iowa was a center of learning theory research, influenced by the work of Clark Hull and his students. Bandura studied with Kenneth Spence, a rigorous experimentalist who instilled in him a commitment to empirical methods and precise theoretical formulation. He received his master’s degree in 1951 and his doctorate in 1952.

During his time at Iowa, Bandura met Virginia Varns, a nursing school instructor who would become his wife. They married in 1952 and had two daughters together. Virginia would remain his partner for more than sixty years until her death in 2011. Bandura has spoken warmly about her influence on his life and work, describing her as a constant source of support and intellectual companionship.

After completing his doctorate, Bandura joined the faculty at Stanford University in 1953, where he would remain for the rest of his career. Stanford provided an intellectually stimulating environment and the resources to pursue ambitious research programs. Bandura rose quickly through the academic ranks, becoming a full professor in 1964 and eventually occupying an endowed chair as the David Starr Jordan Professor of Social Science in Psychology.

Bandura’s early research at Stanford focused on the social origins of aggression. Working with his first doctoral student, Richard Walters, he investigated how children acquire aggressive behaviors through interactions with their families and peer groups. This research challenged the then-dominant psychoanalytic view that aggression arises from innate drives or unconscious conflicts. Bandura and Walters argued instead that aggressive behavior is learned through the same processes that govern the acquisition of any other behavior.

The research program that would make Bandura famous began in the early 1960s with a series of experiments on observational learning that came to be known as the Bobo doll experiments. These studies examined whether children would imitate aggressive behavior they observed in an adult model, even without any direct reinforcement for doing so.

In the classic version of the experiment, preschool children watched an adult play with toys in a room that contained, among other things, an inflatable Bobo doll, a clown-like figure weighted at the bottom so that it would pop back up when knocked down. In the aggressive condition, the adult attacked the Bobo doll violently, punching it, hitting it with a mallet, throwing it in the air, and shouting aggressive phrases like “pow” and “sock him in the nose.” In the control condition, the adult played quietly with other toys and ignored the Bobo doll.

After observing the model, the children were mildly frustrated by being shown attractive toys they were not allowed to play with. They were then taken to another room containing various toys, including a Bobo doll. The results were striking. Children who had observed the aggressive model were far more likely to attack the Bobo doll than children in the control group. Moreover, they often reproduced the specific aggressive acts they had witnessed, using the same techniques and even shouting the same phrases. They had learned these behaviors simply by watching, without any direct instruction or reinforcement.

Subsequent studies elaborated on these findings. Bandura showed that children would imitate aggression seen on film as readily as aggression seen in person. He demonstrated that the consequences observed befalling the model affected whether children would perform the learned behavior. When children saw the model punished for aggression, they were less likely to imitate, but they could still demonstrate the learned behaviors if offered incentives to do so, indicating that they had acquired the behavior even if they chose not to perform it. This distinction between learning and performance became central to Bandura’s theoretical framework.

The Bobo doll studies had immediate implications for understanding the effects of media violence on children. If children learn aggressive behaviors by observing aggressive models, and if filmed models are as effective as live models, then the violence depicted in television shows and movies might be teaching children new forms of aggression. This concern has remained relevant as media have evolved, with contemporary debates about video games echoing the discussions that Bandura’s research originally sparked.

From these studies emerged Bandura’s social learning theory, which he later renamed social cognitive theory to emphasize the cognitive processes involved in observational learning. The theory proposed that learning occurs in a social context through observation of others’ behavior, the consequences of that behavior, and the observer’s expectations about future outcomes. This framework expanded behavioral psychology by incorporating cognitive elements while retaining the emphasis on observable behavior and environmental influence.

Bandura identified several processes that must occur for observational learning to take place. First, the observer must pay attention to the model. Characteristics of both the model and the observer affect attention. People are more likely to attend to models who are distinctive, attractive, prestigious, or similar to themselves. Second, the observer must retain what they have observed, storing the information in memory for later use. Third, the observer must be capable of reproducing the observed behavior, possessing the physical and cognitive abilities to perform the actions. Fourth, the observer must be motivated to perform the behavior, which depends on expected outcomes and self-evaluative reactions.

While social learning theory established Bandura’s reputation, his later work on self-efficacy may prove to be his most enduring contribution. Beginning in the 1970s, Bandura developed the concept of self-efficacy, which refers to people’s beliefs about their capability to perform specific tasks and achieve specific goals. Self-efficacy is not about actual ability but about perceived ability, and these perceptions profoundly influence what people attempt, how much effort they invest, how long they persist in the face of difficulty, and ultimately whether they succeed.

Bandura argued that self-efficacy beliefs are formed through four main sources. The most powerful source is mastery experiences, actual successes in performing the behavior in question. When you try something and succeed, your belief in your ability to succeed again increases. Vicarious experience, observing others succeed, provides another source of efficacy information, particularly when the observer perceives the model as similar to themselves. If someone like me can do it, perhaps I can too. Verbal persuasion, encouragement from others, can boost efficacy beliefs, though its effects are typically weaker than direct experience. Finally, physiological and emotional states influence efficacy judgments. Anxiety, fatigue, and other negative states tend to lower perceived efficacy, while positive affect can enhance it.

Self-efficacy theory has proven remarkably generative, stimulating research across virtually every domain of psychology. Studies have shown that self-efficacy beliefs predict academic achievement, athletic performance, career success, health behaviors, and recovery from illness. Higher self-efficacy is associated with better outcomes in domains ranging from smoking cessation to management of chronic pain to academic persistence. The theory provides a framework for understanding why some people succeed where others with equal ability fail: they believe they can succeed, and this belief sustains their effort and persistence.

For clinical practice, Bandura’s work offers powerful tools for promoting change. The recognition that people learn by observing others suggests that modeling can be an effective therapeutic technique. A therapist treating a client with social anxiety might demonstrate appropriate social behavior, allowing the client to observe and learn without the pressure of immediate performance. Group therapy provides opportunities for clients to observe one another coping with shared challenges, learning from peers who model successful strategies.

Self-efficacy theory provides a framework for understanding why clients often fail to change despite knowing what to do. Knowledge alone is insufficient; people must believe they can execute the required behaviors. A person may know exactly what they need to do to manage their diabetes but fail to do it because they doubt their ability to maintain the necessary lifestyle changes. Effective intervention must address not only skills and knowledge but also the beliefs that determine whether people will actually use what they know.

Building self-efficacy becomes a central therapeutic goal. The most powerful way to build efficacy is through mastery experiences, so therapists should structure treatment to ensure that clients experience early successes. Goals should be set at appropriate levels of difficulty, challenging enough to represent meaningful progress but achievable enough that success is likely. Each success provides evidence of capability that strengthens efficacy beliefs and motivates continued effort.

Vicarious learning has particular relevance for group-based interventions. Clients who observe peers succeeding at tasks they themselves fear often experience increases in their own efficacy beliefs. Support groups, group therapy, and peer mentoring programs all harness this mechanism. The models need not be perfect; indeed, coping models who struggle but ultimately succeed may be more effective than mastery models who perform flawlessly, because observers can more readily identify with someone who faces and overcomes difficulties.

For personal development, Bandura’s research suggests several practical strategies. When you want to develop a new skill or change a behavior pattern, begin with manageable challenges that you can reasonably expect to accomplish. Success builds on success, and early wins establish the efficacy beliefs that sustain later effort. Seek out role models who have achieved what you want to achieve, particularly models who are similar to you in relevant ways. Their success provides evidence that your goals are attainable.

Pay attention to how you interpret your experiences. Efficacy beliefs are influenced not just by outcomes but by how you explain those outcomes. If you succeed and attribute your success to luck or special circumstances, your efficacy beliefs may not increase. If you fail and attribute your failure to stable, internal inadequacy, your efficacy beliefs may be damaged. Learning to make balanced, realistic attributions that acknowledge your role in successes while not catastrophizing failures can help maintain and build efficacy.

Bandura received numerous honors throughout his career, including election to the National Academy of Sciences in 1996, the presidency of the American Psychological Association in 1974, and the James McKeen Cattell Fellow Award from the Association for Psychological Science. In 2016, President Barack Obama presented him with the National Medal of Science, the nation’s highest honor for scientific achievement. A survey published in the Review of General Psychology ranked him as the fourth most cited psychologist of all time, after only Sigmund Freud, Jean Piaget, and Hans Eysenck.

Bandura remained active in research and writing well into his nineties, publishing on topics including moral disengagement, collective efficacy, and the application of social cognitive theory to global challenges including climate change. His intellectual energy and productivity continued until nearly the end of his life. He died on July 26, 2021, at his home in Stanford, California, at the age of ninety-five. His wife Virginia had predeceased him by a decade, and he was survived by his two daughters, Carol and Mary, and several grandchildren.

Timeline of Major Events in the Life of Albert Bandura

1925: Born December 4 in Mundare, Alberta, Canada, to Joseph and Justina Bandura

1949: Graduated from the University of British Columbia with a bachelor’s degree in psychology, receiving the Bolocan Award as the department’s top undergraduate

1951: Received master’s degree in psychology from the University of Iowa

1952: Received doctorate in clinical psychology from the University of Iowa; married Virginia Varns

1953: Joined the faculty at Stanford University, where he would remain for his entire career

1959: Published “Adolescent Aggression” with Richard Walters, presenting early research on social learning and aggression

1961: Conducted the first Bobo doll experiment, demonstrating observational learning of aggressive behavior

1963: Published “Social Learning and Personality Development” with Richard Walters

1965: Published research on vicarious reinforcement and the distinction between learning and performance

1969: Published “Principles of Behavior Modification,” applying social learning theory to clinical intervention

1974: Served as President of the American Psychological Association

1977: Published “Social Learning Theory,” his comprehensive statement of the theory

1977: Introduced the concept of self-efficacy in the journal Psychological Review

1986: Published “Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory,” his magnum opus

1996: Elected to the National Academy of Sciences

1997: Published “Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control,” a comprehensive treatment of his self-efficacy theory

2016: Received the National Medal of Science from President Barack Obama

2021: Died July 26 at his home in Stanford, California, at the age of ninety-five

Selected Bibliography of Albert Bandura

Adolescent Aggression (1959): Co-authored with Richard Walters, this book presented early research on the social origins of aggressive behavior in adolescents, challenging psychoanalytic views of aggression

Social Learning and Personality Development (1963): Co-authored with Richard Walters, this work elaborated social learning theory and its implications for personality development

Principles of Behavior Modification (1969): A comprehensive application of social learning principles to clinical intervention and behavior change

Social Learning Theory (1977): Bandura’s definitive statement of social learning theory, presenting the theoretical framework and research evidence

Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory (1986): Bandura’s most comprehensive theoretical work, elaborating social cognitive theory and its applications across multiple domains

Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control (1997): A comprehensive treatment of self-efficacy theory, presenting research findings and applications across numerous domains

Moral Disengagement: How People Do Harm and Live with Themselves (2016): Bandura’s analysis of the psychological mechanisms that allow people to commit harmful acts while maintaining a positive self-image

Legacy and Influences of Albert Bandura

Albert Bandura’s influence on psychology has been vast and multidimensional. His work challenged and extended the behaviorist tradition by demonstrating that learning occurs through observation as well as direct experience, and by incorporating cognitive processes into accounts of behavior change. His self-efficacy concept has become one of the most widely researched constructs in psychology, with applications in virtually every domain of human functioning.

The Bobo doll experiments and subsequent research on media violence have had lasting impact on discussions of how exposure to violent content affects children and adults. While the debate continues, Bandura’s demonstration that aggressive behaviors can be acquired through observation established the foundation for ongoing research on media effects. Organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics cite this body of research in their recommendations about children’s media consumption.

Social learning theory and its successor, social cognitive theory, have influenced clinical practice across multiple therapeutic approaches. The recognition that modeling is a powerful source of learning has led to the systematic use of modeling techniques in behavior therapy. Therapists demonstrate coping strategies, social skills, and adaptive behaviors that clients can observe and learn. Video modeling has been developed as a technique for treating autism spectrum disorders and other conditions.

In cognitive behavioral therapy, Bandura’s emphasis on the role of cognitive processes in behavior change complements behavioral techniques. The recognition that beliefs about self-efficacy mediate between knowledge and action has informed how CBT addresses motivation and maintenance of behavior change. Therapists attend not only to skill building but to the beliefs clients hold about their capacity to use those skills.

Self-efficacy theory has been particularly influential in health psychology. Research has shown that self-efficacy beliefs predict success in smoking cessation, weight management, exercise adherence, and management of chronic conditions. Studies published in peer-reviewed journals demonstrate that interventions designed to enhance self-efficacy improve health outcomes across diverse populations and conditions. This research has informed the design of health promotion programs worldwide.

In education, Bandura’s work has influenced both teaching practices and theories of academic motivation. Teachers serve as models for students, demonstrating not only academic skills but approaches to learning and problem-solving. The concept of academic self-efficacy has proven central to understanding student motivation and achievement. Interventions designed to build students’ beliefs in their academic capabilities have shown positive effects on persistence and performance.

Organizational psychology has drawn extensively on self-efficacy theory. Research demonstrates that employee self-efficacy predicts job performance, career advancement, and adaptation to organizational change. Training programs designed to build self-efficacy enhance skill acquisition and transfer. Leadership development programs incorporate self-efficacy building as a central component.

Bandura’s later work on collective efficacy, the shared beliefs of groups about their combined capabilities, has extended self-efficacy theory to social and political domains. Research has shown that collective efficacy predicts community health outcomes, neighborhood safety, organizational effectiveness, and political engagement. This work suggests that addressing social problems requires building not only individual efficacy but shared beliefs about the community’s capacity for collective action.

The concept of moral disengagement, which Bandura developed in his later career, has illuminated how ordinary people can participate in harmful activities while maintaining a positive self-concept. This work has applications in understanding corporate misconduct, military atrocities, terrorism, and everyday ethical failures. By identifying the cognitive mechanisms through which people disengage their moral standards, this research suggests strategies for promoting ethical behavior.

0 Comments