When most people hear the word “hypnosis,” they picture a pocket watch swinging back and forth, a stage performer making volunteers cluck like chickens, or perhaps a sinister figure commanding their subject to do something against their will. These images, drawn from entertainment and horror films, have almost nothing to do with the actual phenomenon. Clinical hypnosis, as understood by contemporary neuroscience and practiced by skilled therapists, is something far more interesting and far more useful: a distinct state of consciousness characterized by focused attention, reduced peripheral awareness, and enhanced responsiveness to therapeutic suggestion—a state that can be mapped in the brain and measured in its effects.

The rehabilitation of hypnosis from parlor trick to evidence-based intervention owes much to one figure: Milton H. Erickson, a psychiatrist whose innovative approach transformed how we understand the unconscious mind and its capacity for healing. And among his students, Bill O’Hanlon stands out for translating Erickson’s sometimes mystifying genius into practical frameworks that contemporary therapists can use. Understanding their contributions illuminates not just hypnosis, but the broader possibilities of therapeutic change.

The Neuroscience of the Hypnotic State

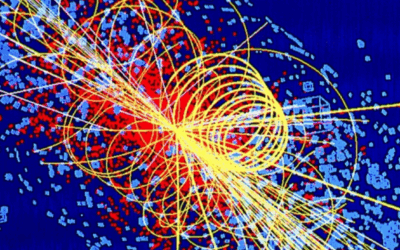

For decades, skeptics could dismiss hypnosis as mere compliance or imagination. Neuroimaging has changed that conversation entirely. Functional MRI and PET scanning have revealed that hypnosis involves distinctive, measurable changes in brain activity—not just subjective reports, but observable alterations in how neural networks communicate.

The brain operates through synchronized networks that handle different functions. Three are particularly relevant to understanding hypnosis: the Default Mode Network (DMN), the Executive Control Network (ECN), and the Salience Network (SN). Research on hypnosis and brain connectivity has demonstrated that hypnosis fundamentally alters the communication between these systems.

Default Mode Network Decoupling

The Default Mode Network, anchored in the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex, activates during self-referential thinking, mind-wandering, and what might be called the “narrative self”—the ongoing internal story of who we are and what we’re doing. During hypnosis, fMRI studies consistently show reduced activity in the DMN, particularly the posterior cingulate cortex. More significantly, there’s a functional decoupling between the DMN (self-processing) and the ECN (task execution).

This disconnection explains one of hypnosis’s most distinctive subjective features: the sense that things are happening by themselves. When the executive system initiates an action—lifting an arm, for instance—without the concurrent engagement of the self-monitoring system that usually tags actions as “mine,” the movement feels involuntary or automatic. The person acts, but the part of the brain that claims authorship is quiet. This isn’t mystical possession; it’s a measurable shift in network connectivity.

The Anterior Cingulate and Conflict Monitoring

The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) serves as the brain’s conflict-detection system—the alarm that fires when things don’t add up. Hypnosis has been shown to alter dACC activity, allowing subjects to process conflicting information without the usual cognitive strain. In the classic Stroop task, where participants must name the ink color of words that spell different colors (the word “RED” printed in blue ink), highly hypnotizable subjects given suggestions that the words are meaningless show reduced dACC activation and eliminate the typical interference effect. They perform effortlessly because the conflict monitoring system has been dampened by suggestion.

Research on resting hypnosis and hypnotizability indicates that highly hypnotizable individuals have higher concentrations of GABA, the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, in the anterior cingulate cortex. This neurochemical profile may provide the biological basis for their ability to inhibit distractions and maintain the profound, singular focus characteristic of deep trance.

The Mind-Body Bridge

The insula, a key node of the Salience Network, integrates autonomic and visceral signals with emotional awareness. Hypnosis increases functional connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (executive intent) and the insula (somatic awareness). This enhanced pathway creates what researchers call a “mind-body bridge”—allowing cognitive suggestions to directly influence physiological parameters like blood flow, pain perception, and stress responses. By modifying the usual critical evaluation of conscious processing, the executive brain can communicate more directly with somatic control centers. This is why hypnosis is so effective for conditions involving the autonomic nervous system.

Milton Erickson: Revolutionizing the Unconscious

Before Milton H. Erickson, clinical hypnosis largely followed what might be called the authoritarian model. The hypnotist was the expert, the subject was passive, and inductions followed standardized scripts delivered with commanding authority: “You are getting sleepy… your eyelids are heavy… you will now enter a deep trance.” This approach, descended from 19th-century traditions, viewed the unconscious as an empty vessel to be filled with therapeutic instructions.

Erickson turned this model inside out. He viewed the unconscious not as a passive receptacle but as a reservoir of wisdom and resources—a creative, generative system that already contained everything needed for healing. The therapist’s job wasn’t to command but to facilitate, not to impose solutions but to help the unconscious find its own.

Utilization: Working With, Not Against

Erickson’s core principle was “utilization”—taking whatever the client presented and weaving it into the therapy. If a client was skeptical and pacing the room, an Ericksonian therapist might say: “That’s right, pace back and forth, and with every step, you can feel yourself settling deeper into your own thoughts.” The resistance isn’t overcome; it’s incorporated. The energy the client brings—even if that energy looks like opposition—becomes the raw material for change.

This principle extended to symptoms themselves. Rather than fighting a symptom, Erickson might prescribe it, alter its timing, or link it to some new context that changed its meaning. A patient with insomnia might be told to stay awake deliberately while lying in bed and focusing on relaxing each muscle—a paradoxical intervention that often produced sleep precisely because the struggle against sleeplessness had been eliminated.

Indirect Suggestion and Therapeutic Metaphor

Where traditional hypnosis used direct commands (“You will no longer crave cigarettes”), Erickson favored indirect approaches: metaphors, stories, ambiguous statements, and embedded commands that bypassed conscious resistance. He might tell a client a lengthy story about a tomato plant growing—seemingly irrelevant—while weaving in suggestions about natural growth, taking in what’s needed, developing at one’s own pace. The conscious mind would follow the story while the unconscious received and processed the therapeutic material.

This approach recognized something important: the conscious mind often resists direct instruction, especially when the instruction touches on emotionally charged material. By speaking to the unconscious in its own language—imagery, metaphor, implication—Erickson could deliver therapeutic suggestions without triggering defensive reactions.

The Handshake Induction and Pattern Interrupts

Among Erickson’s most famous techniques was the handshake induction—a demonstration of what he called “pattern interrupt.” The therapist initiates a handshake but then disrupts the expected motor sequence (perhaps by grasping the wrist instead, or lifting the hand in an unexpected direction). This creates a momentary confusion—a split second where the conscious mind freezes, searching for meaning. In that gap, while the usual critical faculty is suspended, a suggestion for trance can slip through.

This wasn’t manipulation for its own sake. Erickson understood that people often come to therapy trapped in rigid patterns—of thought, behavior, emotion, relationship. The pattern interrupt, whether in a handshake or a therapeutic conversation, creates a moment of openness where something new becomes possible. The confusion is brief and purposeful, a doorway rather than a destination.

Bill O’Hanlon: Making Erickson Practical

Milton Erickson was a genius, but genius can be difficult to learn from. His interventions were often so precisely tailored to individual clients, so reliant on his uncanny attunement to nonverbal cues and unconscious communication, that students sometimes left his training seminars more awed than educated. They’d seen something remarkable but weren’t sure how to replicate it.

Bill O’Hanlon, who studied directly with Erickson in the late 1970s, took on the task of translation. In his book Taproots: Underlying Principles of Milton Erickson’s Therapy and Hypnosis, O’Hanlon identified the patterns beneath Erickson’s seemingly spontaneous brilliance—the recurring structures that could be learned and applied by therapists who lacked Erickson’s particular gifts.

The Class of Problems/Class of Solutions Model

One of O’Hanlon’s key contributions was the “Class of Problems/Class of Solutions” framework. Rather than treating each presenting issue as unique, this model identifies common patterns across problems—what makes something feel “stuck”—and maps these to corresponding categories of intervention. This systematic approach made Ericksonian work more teachable, more reproducible, and more amenable to research.

The model recognizes that problems often share structural features even when their content differs. Someone stuck in a pattern of self-criticism and someone stuck in a pattern of avoiding conflict may have very different stories, but the stuckness itself—the repetitive, automatic quality of the pattern—may respond to similar interventions. By identifying the class of problem, the therapist can draw on a class of solutions rather than starting from scratch with each client.

Solution-Oriented Therapy and Possibility

O’Hanlon went on to develop Solution-Oriented Therapy and, later, Possibility Therapy—approaches that extended Erickson’s influence beyond hypnosis into mainstream psychotherapy. These frameworks share Erickson’s emphasis on resources rather than deficits, solutions rather than problems, and the client’s inherent capacity for change.

A classic O’Hanlonian intervention is the “future-oriented question”: “Let’s say a few weeks or months have passed, and your problem has been resolved. If we were watching a videotape of your life in that future, what would we see you doing differently? What would show us that things had changed?” This technique, which echoes Erickson’s future-pacing work, shifts the client’s attention from the stuck present to a resolved future—often revealing resources and possibilities that were invisible while focused on the problem.

O’Hanlon also introduced practical techniques for helping clients envision change: the time machine, the crystal ball, the letter from a future self. These weren’t mystical exercises but structured ways of accessing the brain’s capacity for prospection—imagining future states—and using that capacity therapeutically.

Demystifying Hypnosis

In Solution-Oriented Hypnosis: An Ericksonian Approach, O’Hanlon did for hypnosis what he’d done for Ericksonian therapy generally: made it accessible. He stripped away the mystique and explained the mechanisms—what trance actually is, how induction works, why suggestions succeed or fail. The book demystifies without diminishing, showing that hypnosis is neither magical nor ordinary but a distinct state with particular properties that can be understood and used.

This demystification matters for contemporary practice. Clients who might be frightened or skeptical of “hypnosis” can understand what they’re actually being offered: a state of focused attention that allows for greater access to unconscious processes and enhanced receptivity to therapeutic suggestions. It’s not about losing control but about gaining access—to resources, memories, and capacities that are harder to reach in ordinary consciousness.

Evidence for Clinical Hypnosis

The question of whether hypnosis “works” has been answered definitively by contemporary research. Meta-analytic reviews of clinical hypnosis spanning two decades of randomized controlled trials have established its efficacy for multiple conditions. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health recognizes evidence for hypnosis in treating IBS, chronic pain, PTSD, and hot flashes, with preliminary data supporting its use for anxiety and smoking cessation.

Pain Management

The most robust evidence for hypnosis is in pain management. A comprehensive meta-analysis including 85 controlled trials and over 3,600 participants found consistent analgesic effects of hypnosis across all pain outcomes, with effect sizes in the medium-to-large range. Highly hypnotizable individuals receiving direct analgesic suggestions demonstrated 42% clinically meaningful reductions in pain.

What makes hypnotic analgesia particularly interesting is its mechanism. Neuroimaging suggests that hypnosis doesn’t necessarily block the sensory signal of pain—somatosensory cortex activity may remain—but disconnects the signal from affective distress. The dACC, which normally generates the “this is bad” component of pain, shows reduced activation. Patients often report: “I can feel it, but it doesn’t hurt.” This selective modification of the pain experience, rather than simple numbing, makes hypnosis valuable as a non-addictive alternative or complement to pharmaceutical approaches.

Trauma and PTSD

For trauma and PTSD, meta-analyses have found large effect sizes favoring hypnotherapy, with improvements maintained at follow-up. A meta-analysis of hypnotherapeutic techniques for PTSD found an overall Cohen’s d of -1.18—a large effect—with benefits persisting at four-week follow-up and beyond.

This efficacy makes sense given what we know about trauma and dissociation. Traumatic memories are often stored in ways that bypass ordinary narrative processing—encoded somatically, fragmented, triggered by sensory cues. Hypnosis, which modifies the brain’s self-referential processing and enhances mind-body connectivity, can provide access to these non-verbal memory systems in ways that ordinary talk therapy may not.

Psychosomatic Conditions

Systematic reviews of medical hypnosis have found robust evidence for conditions involving autonomic dysregulation. Gut-directed hypnotherapy is now a first-line evidence-based treatment for irritable bowel syndrome, working by normalizing visceral hypersensitivity and modulating the gut-brain axis. Studies show sustained remission in the majority of patients, including those who had failed to respond to medication.

For menopausal symptoms, the North American Menopause Society recommends clinical hypnosis as a non-hormonal treatment for hot flashes, with studies showing reductions in frequency and severity of up to 74%. These findings illustrate the power of the mind-body bridge that hypnosis creates—the enhanced connectivity between executive intention and somatic function that allows psychological interventions to produce physiological change.

Safety

Contrary to media portrayals of people getting “stuck” in trance or being made to do things against their will, clinical hypnosis is remarkably safe. A comprehensive review of clinical trials found zero serious adverse events attributable to hypnosis itself. Minor side effects—transient dizziness or headache—occurred in less than 0.5% of participants. Hypnosis is non-invasive, non-addictive, and carries none of the risks associated with pharmacological alternatives.

Schools of Hypnosis: Traditional, Ericksonian, and Neo-Ericksonian

Contemporary clinical hypnosis isn’t monolithic. It encompasses several distinct approaches with different philosophies, techniques, and optimal applications.

Traditional (Authoritarian) Hypnosis

The traditional school, descended from classical 19th and early 20th century methods, positions the hypnotist as authority figure and the subject as passive recipient. Inductions follow formal, standardized scripts: eye fixation, progressive relaxation, direct commands. Suggestions are explicit and commanding: “You are entering a deep sleep,” “You will no longer crave cigarettes.”

This approach still has its place. For simple habit change in motivated clients, for acute pain management in medical settings, and for situations requiring rapid induction, traditional methods can be effective. The structure and clarity can actually be reassuring for some clients. But the approach has limitations: it doesn’t work well with resistant clients, it doesn’t leverage the client’s own resources and creativity, and it positions the therapist as the source of change rather than its facilitator.

Ericksonian (Permissive) Hypnosis

Erickson’s approach, as discussed above, shifted the power dynamic fundamentally. The unconscious is a resource, not a vessel. The therapist guides rather than commands. Resistance is communication, not opposition. Techniques are individualized rather than scripted, utilizing whatever the client brings—including their symptoms and defenses—as material for change.

Ericksonian work excels with complex cases: clients who are ambivalent or resistant, trauma survivors who need a sense of control, people for whom previous therapy has failed. The indirect approaches can bypass defenses that direct suggestions would activate. The emphasis on the client’s own resources supports lasting change rather than therapist-dependent improvement.

Neo-Ericksonian and Integrative Approaches

Contemporary integrative approaches combine Ericksonian insights with modern Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), acceptance-based therapies, and neuroplasticity research. Hypno-CBT, for instance, uses hypnosis to amplify cognitive techniques: instead of just discussing a safe place, the patient is hypnotized to experience it viscerally, engaging the Salience Network and making cognitive restructuring more emotionally potent.

These approaches bring something the purely intuitive Ericksonian style sometimes lacked: systematic protocols that can be tested in randomized controlled trials, manualized treatments that can be replicated across therapists and settings. A 2025 randomized controlled trial comparing Ericksonian Hypnotherapy directly against CBT for anxiety and depression found equivalent overall efficacy, but hypnotherapy produced faster reduction in anxiety symptoms at mid-treatment—suggesting that the somatic regulation provided by hypnosis may offer quicker relief for physiological anxiety than purely cognitive approaches.

Hypnosis and Trauma: Beyond Simple Symptom Relief

The connection between hypnosis and trauma runs deep—deeper than most practitioners realize. Research has identified a significant link between high hypnotizability and dissociative capacity. Patients diagnosed with Dissociative Identity Disorder consistently score at the ceiling of standardized hypnotizability scales. This isn’t coincidence. High hypnotizability appears to be a trait—perhaps a kind of neural flexibility—that can serve either adaptive or pathological purposes depending on circumstances.

When a highly hypnotizable child experiences trauma, they have an unusual capacity for mental escape. They can dissociate the traumatic experience into a separate memory compartment, sequestering it from ordinary consciousness. This is an adaptive defense in the moment—it allows the child to survive unbearable experience. But if the dissociation becomes chronic, if the walled-off material remains unintegrated, the same capacity that protected the child becomes the engine of ongoing fragmentation.

This has profound implications for treatment. The capacity for hypnosis that may have enabled dissociative defenses can also enable their healing. In skilled hands, hypnosis provides controlled access to dissociated material—allowing traumatic memories to be processed, integrated, and released. The same neural flexibility that created the fragmentation can create integration.

But this requires skill and caution. The power of hypnosis to access unconscious material can also create false memories if used carelessly. The forensic use of hypnosis to “recover” memories has been largely discredited precisely because the hypnotic state increases both the volume of recall and its susceptibility to suggestion. What’s remembered may be real, confabulated, or some mixture—and the subject can’t reliably tell the difference. This is why therapeutic hypnosis for trauma requires careful attention to suggestibility, pacing, and the integration of whatever material emerges.

Hypnosis in the Context of Brain-Based Therapy

From the perspective of modern brain-based trauma treatment, hypnosis makes sense for reasons that Erickson intuited but couldn’t fully articulate. Traumatic memories are often encoded subcortically—in the limbic system and brainstem rather than the cortical structures that support narrative processing. This is why trauma survivors can “know” cognitively that the danger is past while their bodies continue responding as if threat is present. The body keeps the score, as Bessel van der Kolk put it, even when the conscious mind has moved on.

Hypnosis, by modifying the relationship between executive and default mode processing, can provide access to these subcortical systems. The enhanced mind-body connectivity characteristic of the hypnotic state allows therapeutic work to reach levels that pure talk therapy may not touch. This is similar to what happens in other brain-based approaches: Brainspotting uses eye position to access subcortical processing; EMDR uses bilateral stimulation to facilitate the integration of traumatic material; somatic approaches work with the body’s stored trauma responses directly.

These modalities aren’t competitors; they’re complementary approaches to the same fundamental challenge: how to help people access and integrate material that isn’t available to ordinary conscious processing. A therapist trained in multiple modalities can move fluidly between them, using whatever approach provides the best access for a particular client at a particular moment.

The Unconscious as Resource: A Depth Psychology Perspective

From a depth psychological perspective, Erickson’s view of the unconscious as a reservoir of resources rather than a repository of pathology represents a significant departure from classical psychoanalysis. Freud’s unconscious was a cauldron of repressed wishes and forbidden impulses—something to be managed and controlled. Erickson’s unconscious is creative, wise, and fundamentally oriented toward healing—something to be accessed and trusted.

Donald Kalsched’s work on archetypal defenses offers a framework for understanding both perspectives. The traumatized psyche does develop defenses—protective structures that may become rigid and self-limiting. But beneath these defenses lies a creative, generative core that Kalsched, following Jung, calls the Self. Healing involves neither forcing past defenses nor simply reinforcing them, but creating conditions where the defended self can gradually emerge and integrate.

Hypnosis, in this view, is a tool for creating those conditions. The modified consciousness of trance can bypass surface defenses without overwhelming the system—allowing access to deeper resources while maintaining safety. Erickson’s permissive approach, which accepts rather than fights resistance, aligns with the depth psychological principle that defenses serve protective purposes and must be respected even as they’re gradually modified.

Parts-based approaches, whether derived from Internal Family Systems, ego state therapy, or Jungian active imagination, share this fundamental orientation. The psyche contains multiple elements—parts, sub-personalities, complexes—that may be in conflict or out of communication. Therapy involves facilitating dialogue among parts, integrating what’s been fragmented, and restoring a functional wholeness that doesn’t require any part to be eliminated or suppressed.

Dispelling the Myths

Despite the scientific advances, public perception of hypnosis remains contaminated by theatrical distortions and forensic pseudoscience. A few clarifications:

Stage Hypnosis Is Performance Art

Stage hypnosis relies on selection bias, social compliance, and showmanship—not mystical control. The performer screens the audience with suggestibility tests, inviting only the 10-15% with highest hypnotic capacity onto the stage. These individuals, under the bright lights and social pressure of performance, do things they might otherwise suppress—but they’re not being controlled against their will. They’re highly hypnotizable people in a social context that gives permission for unusual behavior.

Hypnosis Is Not Mind Control

Research consistently shows that hypnotized subjects cannot be made to do things that violate their fundamental values or interests. The hypnotic state involves altered processing, not obliterated judgment. People in trance can refuse suggestions, emerge from trance if they feel unsafe, and generally remain in contact with their own values and limits even when experiencing altered consciousness.

Hypnosis Is Not a Truth Serum

Perhaps the most damaging myth is that hypnosis can retrieve accurate, “repressed” memories like a video recorder rewinding to a crime scene. Scientific consensus is clear: hypnosis increases the volume of recall while decreasing its accuracy. The heightened suggestibility of trance makes subjects prone to confabulation—unconsciously fabricating details to fill gaps. Worse, hypnosis produces “memory hardening”: hypnotized witnesses become supremely confident in their recall even when it’s entirely false. This is why forensic hypnosis has been largely abandoned in legal settings.

You Can’t Get “Stuck” in Trance

The idea of someone getting permanently stuck in hypnosis has no basis in clinical reality. Trance is a natural state that the brain moves into and out of regularly—during focused attention, daydreaming, absorption in a book or movie. Clinical hypnosis deliberately induces this state, but the state naturally resolves. Even without a formal “wake-up” suggestion, a hypnotized person will simply return to ordinary consciousness within minutes, possibly after a brief period of light sleep.

When to Consider Hypnosis

Clinical hypnosis may be particularly helpful for:

Pain management, both acute (medical procedures, dental work, childbirth) and chronic (fibromyalgia, back pain, headaches). Anxiety and stress-related conditions, particularly when these have somatic components. Psychosomatic and functional disorders (IBS, functional dyspepsia, chronic fatigue). Trauma and PTSD, especially when conventional talk therapy has reached its limits. Habit change (smoking cessation, weight management) in motivated clients. Performance enhancement (athletics, public speaking, creativity) when self-limiting beliefs interfere. Sleep disorders, particularly when anxiety or rumination disrupts sleep onset.

Hypnosis is not appropriate for everyone. Hypnotizability varies significantly across individuals—about 10-15% of the population are highly hypnotizable, the majority are moderately hypnotizable, and another 10-15% are minimally responsive to hypnotic suggestion. While even low hypnotizables can benefit from hypnotic techniques, the dramatic effects often described in the literature are most likely for those with high hypnotic capacity.

Additionally, hypnosis should be approached carefully with certain populations: those with active psychosis, severe dissociative disorders (without specialized training), or conditions where altered consciousness could pose risks. Hypnosis is a tool, powerful but not universally applicable.

Finding Skilled Practice

The efficacy of hypnosis depends heavily on the skill of the practitioner. Formal training through organizations like the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis (ASCH) or the Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis (SCEH) provides foundational competencies. But beyond certification, look for practitioners who integrate hypnosis with broader clinical skills—understanding of the conditions they’re treating, ability to establish therapeutic rapport, and flexibility in approach.

At Taproot Therapy Collective, we incorporate hypnotic principles and techniques within a broader framework of brain-based trauma treatment. We draw on Ericksonian utilization, indirect suggestion, and the recognition that the unconscious contains resources for healing—while integrating these with Brainspotting, EMDR, somatic approaches, and parts-based therapy. This integration allows us to use whatever approach provides the best access for a particular client at a particular moment.

We serve clients in Hoover and greater Birmingham, and offer teletherapy throughout Alabama including Montgomery and Tuscaloosa.

The Legacy Continues

Milton Erickson died in 1980, but his influence continues to expand. The Ericksonian approach has shaped not just clinical hypnosis but solution-focused therapy, strategic therapy, neuro-linguistic programming, and multiple integrative approaches. Bill O’Hanlon’s work—translating Erickson’s intuitive genius into learnable principles—has made these insights accessible to generations of therapists who never had the opportunity to study with the master directly.

More broadly, Erickson’s fundamental insight—that the unconscious is a resource rather than a problem, that resistance contains communication, that change happens through utilization rather than opposition—has become part of how contemporary therapy thinks about its work. Even therapists who don’t use formal hypnosis often draw on Ericksonian principles when they meet clients where they are, work with rather than against defenses, and trust the client’s capacity for self-healing.

The neuroscience has caught up with what Erickson intuited: consciousness is modifiable, the brain has multiple modes of processing, and altered states can provide access to capacities unavailable in ordinary awareness. What Erickson accomplished through clinical genius, we can now understand through fMRI, PET scanning, and quantitative EEG. The mystery hasn’t been eliminated—there’s still much we don’t understand about how hypnosis works—but it’s been illuminated. And in that illumination, hypnosis has found its place: not as parlor trick or mystical practice, but as a legitimate, evidence-based tool for therapeutic change.

The pocket watch is gone. The science has arrived. And Erickson’s fundamental faith—that the mind contains resources for its own healing, if we can only learn to access them—has been validated by the most rigorous tools contemporary neuroscience can offer.

0 Comments