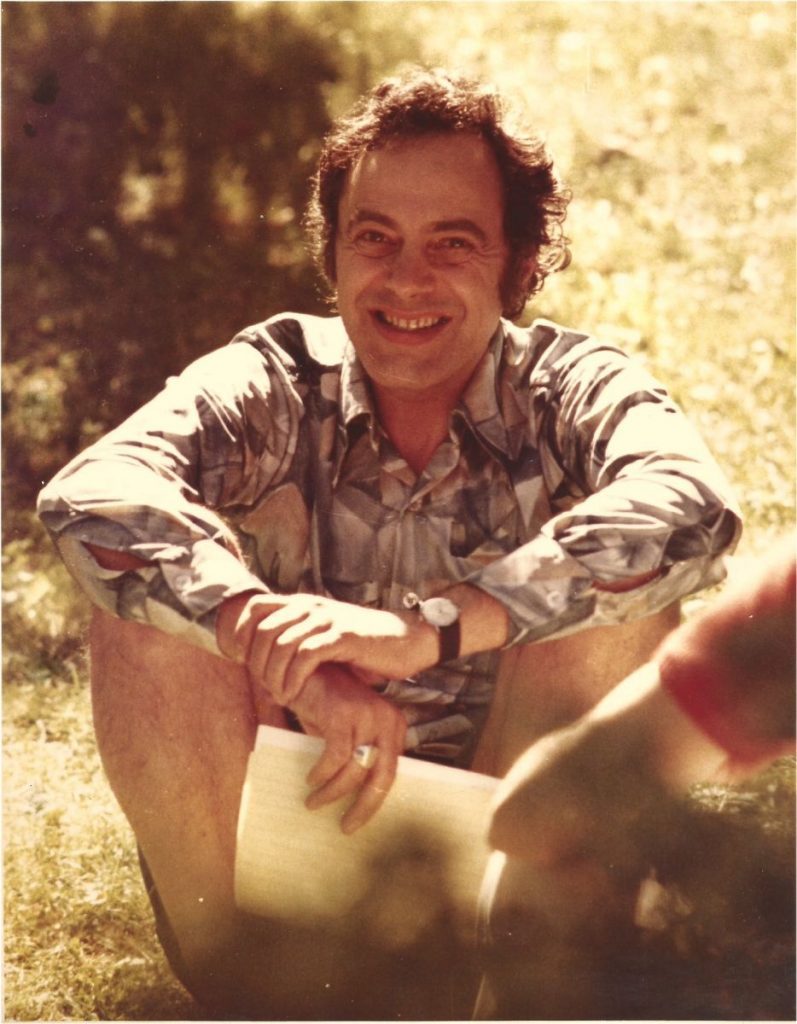

In the landscape of contemporary psychotherapy, a quiet revolution has been unfolding—one that moves us away from the primacy of thoughts and verbal processing toward the wisdom held in the body’s deeper knowing. At the heart of this shift stands Eugene Gendlin, a philosopher and psychologist whose work in the 1960s and 70s laid the groundwork for much of what we now understand about embodied healing.

The Felt Sense: Gendlin’s Revolutionary Discovery

Eugene Gendlin’s seminal contribution to psychotherapy emerged from a deceptively simple question: Why does therapy work for some people and not others? Through meticulous research at the University of Chicago, Gendlin discovered that successful therapy clients shared a common characteristic—they naturally accessed what he termed the “felt sense,” a pre-verbal, bodily knowing that exists beneath our conceptual understanding.

The felt sense is not an emotion, though it contains emotional tones. It’s not a thought, though it carries meaning. It’s that murky, unclear sensation in your body when you’re trying to find the right word, when something feels “off” but you can’t quite articulate why, or when a decision feels right in your gut before your rational mind can explain it.

Gendlin formalized this process into a technique called Focusing, teaching people to deliberately attend to this bodily knowing. The radical insight? Real therapeutic change doesn’t come from achieving new insights or correcting distorted thoughts—it comes from making contact with this pre-conceptual bodily wisdom and allowing it to unfold.

The Brainstem Revolution: Why Subcortical Processing Matters

What Gendlin understood intuitively, neuroscience has since confirmed: the most profound aspects of our experience are held not in our neocortex—our thinking brain—but in the subcortical regions, particularly the brainstem and limbic system. These ancient parts of our nervous system hold our survival patterns, our attachment experiences, and our deepest traumas.

This is why talking about problems, while sometimes helpful, often fails to create lasting change. We’re trying to use the thinking brain to solve problems that are encoded in parts of the brain that don’t speak in words. The brainstem doesn’t understand narrative or logic—it responds to sensation, to felt safety, to the body’s implicit knowing.

Gendlin’s genius was recognizing that we need to meet the body where it is, in its own language of sensations and felt meanings, rather than trying to translate everything into cognitive understanding.

A Tapestry of Influence: Gendlin’s Legacy in Modern Somatic Therapies

Somatic Experiencing and Peter Levine

Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing (SE) shares deep roots with Gendlin’s work. Both approaches recognize that trauma is held in the body and that healing requires tracking subtle bodily sensations rather than retelling traumatic stories. SE practitioners guide clients to notice the “felt sense” of incomplete survival responses—the trembling, the impulse to run, the tension of thwarted fight responses—and allow these patterns to complete organically.

Like Gendlin, Levine understood that the thinking mind often interferes with the body’s innate healing processes. Both methods emphasize titration, pendulation, and honoring the body’s own pace of change.

Brainspotting and Dr. David Grand

Dr. David Grand’s Brainspotting, developed in 2003, represents an elegant extension of body-centered processing. By maintaining eye positions that correlate with activation in subcortical brain regions, Brainspotting accesses material that bypasses our cortical defenses. Grand explicitly acknowledges the importance of the felt sense, teaching therapists to help clients drop beneath their thoughts and into bodily awareness.

The Brainspotting mantra—”Where you look affects how you feel”—is fundamentally about accessing subcortical processing. The relevant eye position creates a direct pathway to brainstem and limbic material, allowing the body to process what the thinking mind cannot reach.

Lifespan Integration and Peggy Pace

Peggy Pace’s Lifespan Integration (LI) therapy offers another iteration of this body-centered wisdom. While LI uses a timeline of memories as its structure, the therapeutic action happens through the client’s bodily response to being repeatedly oriented to present safety while touching traumatic material. The felt sense of “I survived, I’m here now” integrates at a subcortical level.

LI practitioners are trained to notice subtle shifts in clients’ bodies—the softening of facial muscles, the deepening of breath, the settling of the nervous system—rather than focusing primarily on cognitive insights.

The Paradigm Shift: From Insight to Integration

What unites Gendlin’s Focusing with these contemporary approaches is a fundamental paradigm shift in how we understand therapeutic change:

Old paradigm: Bringing unconscious material to conscious awareness creates change. Understanding why we feel the way we do provides mastery over our emotions.

New paradigm: Therapeutic change happens when the subcortical brain experiences something new—safety, completion, or integration. The thinking brain’s job is primarily to stay out of the way and allow deeper processes to unfold.

This doesn’t mean thoughts are irrelevant. But it repositions them as secondary to the body’s processing. Our conceptual understanding is like a map of the territory—useful for navigation, but not the territory itself. Healing happens in the territory, in the living, breathing, feeling body.

Practical Implications for Contemporary Practice

For therapists trained in traditional talk therapy, embracing Gendlin’s legacy requires a significant reorientation:

- Slowing down: The felt sense cannot be rushed. It requires space, patience, and a willingness to tolerate uncertainty.

- Privileging sensation over story: When clients share their narratives, help them find the felt sense beneath the words. “Where do you feel that in your body?”

- Trusting the implicit: The body’s wisdom often manifests as vague, unclear sensations. These “muddy” feelings are not problems to be clarified—they’re the raw material of transformation.

- Recognizing that not-knowing is therapeutic: Clients don’t need to understand why they feel the way they do. They need to be with how they feel with compassionate attention.

The Body as Oracle

Eugene Gendlin’s work reminds us that we are not primarily thinking beings who occasionally have bodies—we are embodied beings whose thoughts emerge from a much deeper somatic foundation. The brainstem, that ancient core of our nervous system, holds truths that our sophisticated cortex cannot access through analysis alone.

As psychotherapy continues to evolve, Gendlin’s influence flows through an ever-widening stream of body-centered modalities. Whether we call it Focusing, Somatic Experiencing, Brainspotting, or Lifespan Integration, we’re engaged in the same essential task: creating the conditions for the body’s innate healing wisdom to emerge.

The revolution Gendlin began is not yet complete, but its direction is clear. Effective therapy happens not when we think our way through problems, but when we feel our way through them—when we trust the body to know what the mind cannot say, and give it the space and attention to speak.

Timeline

Early Life and Education (1926-1950s)

Eugene Gendlin was born in Vienna, Austria in 1926. His family fled Nazi persecution, emigrating to the United States when Gendlin was still a child. This experience of displacement and survival would later influence his understanding of how the body holds unspoken experience.

Key Educational Milestones:

- 1950: Received his PhD in Philosophy from the University of Chicago

- 1950s-1960s: Worked closely with renowned psychologist Carl Rogers at the University of Chicago Counseling Center

- 1958-1962: Conducted groundbreaking research examining what makes psychotherapy effective

The Research Years (1960s-1970s)

Gendlin’s most significant contribution emerged from his meticulous analysis of hundreds of therapy session recordings. Unlike most researchers who studied what therapists did, Gendlin focused on what successful clients did differently.

Major Discovery (1964): Published findings showing that therapeutic success could be predicted from how clients talked about their problems—specifically, whether they accessed a bodily felt sense of their issues rather than just intellectualizing about them.

1978: Published “Focusing,” his seminal book for general audiences, which has sold over 500,000 copies and been translated into seventeen languages. The Focusing Institute continues to train practitioners worldwide in this method.

1981: Published “Focusing-Oriented Psychotherapy,” a manual for clinicians integrating Focusing into therapeutic practice.

Academic Career and Philosophical Work

1964-1995: Professor of Psychology and Philosophy at the University of Chicago, where he continued developing his philosophy of the implicit and explicating process.

1962: Published “Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning,” establishing his philosophical foundation for understanding how meaning emerges from bodily experience rather than purely cognitive processes.

1997: Published “A Process Model,” his most comprehensive philosophical work, detailing how body and environment interact to create experience and meaning.

Later Years and Legacy (1990s-2017)

Gendlin continued teaching, writing, and supervising until his death in 2017 at age 90. He established The International Focusing Institute, which maintains training standards and continues spreading his work globally. His influence extends far beyond Focusing practitioners, shaping the entire field of somatic psychology.

Understanding Gendlin’s Major Theories and Concepts

The Felt Sense: The Core Discovery

The felt sense is Gendlin’s most important theoretical contribution to psychotherapy. It refers to a pre-verbal, bodily awareness of situations, problems, or experiences—a holistic body sensation that carries meaning before words can articulate it.

Characteristics of the Felt Sense:

- Located in the body, typically the torso (chest, stomach, throat)

- Vague, unclear, “murky”—not a simple emotion like “angry” or “sad”

- Contains implicit meaning that can unfold into new understanding

- Changes and shifts when properly attended to

- More comprehensive than conscious thought—holds the “whole” of a situation

Unlike emotions, which are identifiable and nameable, the felt sense is that unclear bodily sensation when something feels “off,” when you’re searching for the right word, or when you know something but can’t yet articulate it.

The Focusing Process: Six Steps to Accessing Bodily Wisdom

Gendlin formalized Focusing into a teachable six-step process, described in detail at Focusing.org:

- Clearing a Space: Creating inner room by acknowledging problems without diving into them

- Felt Sense: Selecting one issue and sensing its bodily quality as a whole

- Finding a Handle: Discovering a word, phrase, or image that matches the felt sense

- Resonating: Checking the handle against the felt sense to ensure fit

- Asking: Gently inquiring what about the problem gives it this particular quality

- Receiving: Welcoming whatever comes, even if just a small step

The process emphasizes patience, allowing the body’s wisdom to emerge at its own pace rather than forcing cognitive understanding.

The Philosophy of the Implicit

Gendlin’s philosophical work centered on what he called “the implicit”—the vast, pre-conceptual bodily knowing that exists before and beneath our explicit thoughts and language.

Key Philosophical Concepts:

Experiencing: The ongoing flow of felt, bodily life that is the basis for all meaning. According to Gendlin, we don’t think and then feel—we feel, and thinking emerges from that feeling.

The Interaction First Principle: Meaning doesn’t exist in isolated minds or external objects but emerges from the interaction between body and environment. The University of Chicago Press published his major philosophical works detailing this interaction.

Carrying Forward: Real change occurs when stuck patterns are “carried forward”—when something that was blocked or incomplete moves into new forms and possibilities. This happens through attending to the felt sense, not through analysis.

Process vs. Content: Gendlin distinguished between the content of what we think about and the process of how meaning emerges from bodily experience. Therapy works by attending to process, not just content.

Research Foundations: What Makes Therapy Work?

Gendlin’s research challenged fundamental assumptions about psychotherapy. His studies, published in peer-reviewed journals including the Journal of Consulting Psychology, demonstrated:

- Therapeutic success was independent of theoretical orientation: Whether therapists practiced psychoanalysis, client-centered therapy, or other approaches made less difference than client characteristics

- Experiencing Scale: Gendlin developed a measure showing that clients who spoke from bodily felt experience (high experiencing) improved more than those who remained intellectually detached (low experiencing)

- Predictor of Outcome: Success could be predicted as early as the second session based on whether clients accessed felt experiencing

- Not about Techniques: What therapists did mattered less than whether clients naturally or were guided to contact bodily felt experience

These findings are documented at the American Psychological Association database of research outcomes and revolutionized understanding of therapeutic change mechanisms.

The Neuroscience Connection: Why the Brainstem Matters

Gendlin’s experiential understanding has been validated by contemporary neuroscience research. The brainstem and subcortical structures—not the neocortex—are primary in therapeutic change.

The Triune Brain and Trauma Processing

Paul MacLean’s triune brain model, though simplified, helps illustrate why Gendlin’s approach works:

- Neocortex: Thinking, reasoning, language

- Limbic System: Emotions, memory, attachment

- Brainstem (“Reptilian Brain”): Survival responses, arousal regulation, basic safety assessment

Trauma, attachment wounds, and core survival patterns are encoded in the brainstem and limbic system. These regions don’t process verbal language—they respond to sensation, movement, and felt safety. This is why talking about trauma often fails to create lasting change.

Polyvagal Theory and Felt Safety

Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory, detailed in his research at The Polyvagal Institute, explains how the vagus nerve mediates our sense of safety. The body must feel safe at a physiological level (neuroception) before higher-order processing can occur.

Gendlin’s Focusing creates conditions for this felt safety by:

- Slowing down

- Accepting unclear, vague sensations without forcing clarity

- Creating a compassionate, non-judgmental relationship with inner experience

- Allowing the body’s own pace of unfolding

Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down Processing

Contemporary trauma therapy distinguishes between:

Top-Down Processing: Using the neocortex to regulate emotion and behavior (cognitive behavioral approaches)

Bottom-Up Processing: Accessing subcortical material directly through body sensation, movement, and felt experience (somatic approaches)

Gendlin’s work is fundamentally bottom-up. The felt sense arises from subcortical processing—it’s the body’s wisdom speaking before the thinking mind interprets or analyzes.

Research published in journals like Frontiers in Psychology and Clinical Psychology Review increasingly validates bottom-up approaches for trauma, chronic stress, and complex PTSD.

Practical Applications: Integrating Gendlin’s Work into Clinical Practice

Assessment: Recognizing Focusing Ability

Not all clients naturally access felt sense awareness. Assessment involves:

High Experiencers (Good Focusers):

- Naturally pause and sense inwardly

- Use phrases like “it feels like…”, “there’s something…”, “I’m not sure how to say this…”

- Tolerate ambiguity and unclear feelings

- Describe bodily sensations when discussing problems

Low Experiencers:

- Stay in abstract analysis

- Speak quickly without pausing to sense inwardly

- Focus on external details or other people’s behavior

- Intellectualize or rationalize

- Avoid or dismiss bodily sensations

The good news: Focusing can be taught. Clients who don’t naturally access felt sense can learn through guided practice.

Teaching Focusing in Session

Basic Invitation to Felt Sense:

- “Take a moment and sense inside your body—where do you feel that?”

- “If you check your body right now about this situation, what do you notice?”

- “Let yourself sense what this whole issue feels like in your body…”

- “Can you find where that lives in your body?”

Working with the Felt Sense:

- Allow silence and time for sensing

- Help clients find words/images that match without forcing clarity

- Notice and welcome small shifts

- Don’t require clients to understand why they feel what they feel

Common Clinical Mistakes

Over-Directing: Telling clients what they should feel or rushing the process

Premature Interpretation: Explaining the felt sense rather than letting it unfold

Staying in Content: Getting caught in the story without dropping into sensation

Requiring Clarity: Insisting clients articulate clearly what is inherently vague

Skipping Past Discomfort: Moving too quickly through difficult feelings

Integration with Other Modalities

Focusing integrates with virtually any therapy approach:

CBT + Focusing: Use felt sense to identify core beliefs before cognitive restructuring

EMDR + Focusing: Check felt sense when installing positive cognitions

Psychodynamic + Focusing: Access felt sense of unconscious material

Mindfulness-Based Therapies: Focusing is a specific form of mindfulness practice

Attachment-Focused Work: Use felt sense to explore attachment patterns and relational needs

Research Support and Evidence Base

Outcome Research

Studies on Focusing and Focusing-Oriented Therapy demonstrate:

- Effectiveness for Depression: Research published in Psychotherapy Research shows Focusing-Oriented Therapy reduces depressive symptoms comparably to CBT

- Anxiety Reduction: Studies demonstrate decreased anxiety scores following Focusing training

- Increased Psychological Well-being: Self-report measures show improvements in general well-being

- Body Awareness: Focusing increases interoceptive awareness (body sensation detection)

Process Research

Research examining how Focusing works shows:

- Experiencing Levels Predict Outcome: Higher experiencing scores correlate with better therapy outcomes across modalities

- Felt Sense Moments: Sessions containing felt sense exploration show greater symptom reduction

- Teaching Effectiveness: Clients can be taught to access felt sense, improving outcomes

Neuroimaging Studies

Recent neuroimaging research, though limited, suggests:

- Focusing activates insula (interoception) and anterior cingulate cortex (emotion regulation)

- Decreased amygdala activation during Focusing compared to rumination

- Increased connectivity between subcortical and cortical regions

The National Center for Biotechnology Information database contains peer-reviewed research on Focusing and body-centered therapies.

Training and Certification

Focusing Training Levels

The International Focusing Institute offers structured training:

Level 1: Introduction to Focusing for personal use Level 2: Focusing with others (companionship) Certification: Professional certification requires extensive training and supervision

Focusing-Oriented Therapy Training: Additional specialized training for licensed therapists

Professional Organizations

- The International Focusing Institute: Primary organization for Focusing training worldwide

- Focusing Institute of New York: Regional training center

- European Focusing Network: Coordinates training across Europe

Criticisms and Limitations

Valid Concerns

Limited Large-Scale RCTs: While research supports Focusing, large randomized controlled trials are limited compared to CBT or other mainstream approaches

Difficulty Teaching: Not all therapists find it easy to teach Focusing; it requires comfort with ambiguity and patience

Client Suitability: Severely dissociated clients or those with limited body awareness may need preparatory work before Focusing is appropriate

Cultural Considerations: Body-focused approaches may not align with all cultural values around emotional expression and introspection

Addressing Misconceptions

“It’s Just Mindfulness”: While related, Focusing involves active questioning and unfolding, not just observing

“It’s Too Vague”: The vagueness is the point—forcing clarity prematurely blocks the process

“It Takes Too Long”: Focusing moments can be brief; the method is flexible

The Paradigm Shift: Rethinking How Therapy Works

Old Paradigm: Insight-Oriented Therapy

Traditional psychotherapy assumed:

- Unconscious material must become conscious

- Understanding causes of problems creates change

- Interpretation and insight are therapeutic mechanisms

- Cognitive change precedes emotional/behavioral change

- The thinking mind can regulate the emotional mind

New Paradigm: Body-Centered Processing

Gendlin’s legacy, amplified through contemporary somatic therapies:

- Subcortical processing drives change

- The body must experience something new (safety, completion, integration)

- Thinking brain’s role is not to control but to stay present with body process

- Healing happens in the brainstem and limbic system

- Conceptual understanding follows somatic integration, not vice versa

This paradigm shift doesn’t eliminate thinking or insight—it repositions them as secondary to embodied processing.

Clinical Implications

For Assessment: Evaluate capacity for interoception and body awareness, not just symptoms

For Treatment Planning: Choose interventions that access subcortical processing

For Session Structure: Prioritize slowing down and sensing over quick problem-solving

For Therapist Training: Develop personal Focusing practice to embody the approach

For Measuring Progress: Track body-based indicators (nervous system regulation, somatic awareness) alongside symptom reduction

The Brainstem Truth: Why Subcortical Healing Matters

The most profound implication of Gendlin’s work, validated by neuroscience, is this: the brainstem and subcortical structures hold the keys to healing that our cortical thinking cannot access through analysis alone.

What the Brainstem Holds

- Survival responses: Fight, flight, freeze patterns

- Attachment templates: Early relational experiences

- Arousal regulation: Our baseline nervous system state

- Implicit memory: Body-based memories without conscious narrative

- Safety assessment: Neuroception (below conscious awareness)

Why Talking Isn’t Enough

Talk therapy engages the neocortex—the most recent evolutionary addition to our brain. But trauma, chronic stress, developmental wounds, and attachment injuries are encoded in the brainstem and limbic system—ancient structures that existed long before humans developed language.

These regions:

- Don’t understand words

- Don’t respond to logic

- Can’t be convinced or reasoned with

- Operate on sensation, rhythm, safety cues

- Change through direct experience, not insight

This is why someone can “know” they’re safe but still experience panic attacks, why understanding childhood origins of patterns doesn’t automatically change them, why insight feels helpful but doesn’t always translate to lasting change.

The Path to Subcortical Change

Gendlin discovered empirically what neuroscience later confirmed: accessing the felt sense creates a bridge between cortical awareness and subcortical processing. When we attend to body sensations with gentle, accepting awareness, we create conditions for subcortical material to surface, process, and integrate.

This is why Focusing, Somatic Experiencing, Brainspotting, and Lifespan Integration all work: they bypass cortical defenses and meet the body where healing actually happens—in the brainstem, in the vagus nerve, in the implicit memory systems that hold our deepest patterns.

Conclusion: Gendlin’s Enduring Legacy

Eugene Gendlin died in 2017, but his influence continues expanding throughout psychotherapy. His core insight—that the body holds wisdom inaccessible to conceptual thought—has become foundational to trauma treatment, somatic psychology, and contemporary neuroscience-informed therapy.

Key Takeaways for Clinicians

- Slow Down: Therapeutic change requires time for felt sense to emerge

- Trust the Body: The implicit carries more wisdom than our explicit theories

- Stay With Experience: Don’t rush to interpretation or meaning-making

- Develop Your Own Practice: Personal Focusing practice enhances clinical effectiveness

- Integrate Broadly: Focusing principles enhance virtually any therapeutic approach

The Future of Focusing-Informed Practice

As neuroscience increasingly validates bottom-up processing, Gendlin’s work becomes more relevant, not less. Future developments likely include:

- Integration with neurofeedback and biofeedback

- Combination with psychedelic-assisted therapy

- Enhanced understanding of interoceptive processing

- Broader adoption in mainstream clinical training

- Research demonstrating specific neural correlates of felt sense

For Further Learning:

- The International Focusing Institute: https://focusing.org/

- Training in Somatic Experiencing: https://traumahealing.org/

- Brainspotting Training: https://brainspotting.com/

- Lifespan Integration: https://lifespanintegration.com/

- Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute: https://www.sensorimotorpsychotherapy.org/

Key Publications by Eugene Gendlin:

- “Focusing” (1978) – For general audiences

- “Focusing-Oriented Psychotherapy” (1996) – For clinicians

- “Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning” (1962) – Philosophical foundations

- “A Process Model” (1997) – Comprehensive philosophical work

This article honors Eugene Gendlin’s contributions to psychotherapy and the continuing evolution of body-centered, trauma-informed practice. May his insights continue guiding therapists toward the deeper wisdom the body holds.

0 Comments