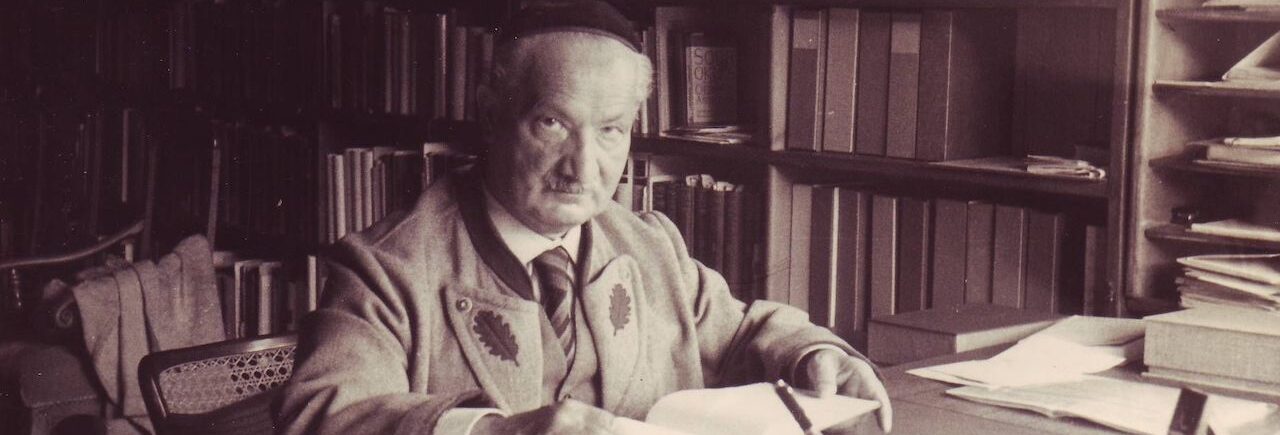

Martin Heidegger and the Quest for Being: The Philosopher who Wrecked and Rebuilt Western Thought

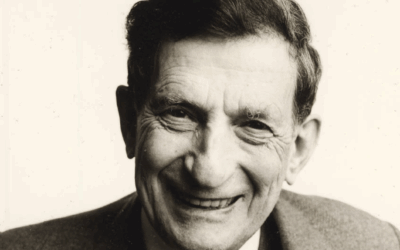

Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) is the “Dark Giant” of 20th-century philosophy. He is perhaps the most influential philosopher since Hegel, and certainly the most controversial. His magnum opus, Being and Time (1927), did not just modify philosophy; it attempted to destroy the entire history of Western metaphysics and rebuild it from the ground up.

For the psychotherapist, Heidegger is the gateway to understanding what it means to be human—not as a biological machine, but as a being who cares, suffers, and dies. His work laid the foundation for Existential Psychotherapy, Daseinsanalysis, and much of postmodern thought. However, his legacy is permanently stained by his membership in the Nazi party. To read Heidegger is to grapple with the terrifying possibility that profound wisdom and profound moral failure can coexist in the same mind.

This guide explores Heidegger’s destruction of the “Cartesian Ego,” his invention of Hermeneutic Phenomenology, his impact on trauma treatment, and the thinkers he influenced—from the Frankfurt School to the French Existentialists.

I. The Core Project: The Question of Being (Seinfrage)

Heidegger argued that Western philosophy had forgotten the most important question: “What does it mean to be?”

Since Plato, philosophers had focused on beings (things, objects, atoms, ideas). They treated “Being” (the fact that things exist at all) as self-evident. Heidegger called this the “Seinsvergessenheit” (Forgetfulness of Being). To fix this, he introduced a new concept of the human: Dasein.

What is Dasein?

Heidegger rejected the terms “Subject,” “Ego,” or “Consciousness.” These terms imply that we are isolated minds trapped inside skulls, looking out at a world.

Instead, he used the term Dasein (literally “Being-There”).

* We are not in the world like water in a glass.

* We are in the world like a mood is in a room.

Dasein is “Being-in-the-world.” We are inextricably woven into the fabric of our environment, our history, and our relationships. This shattered the Cartesian model used by early psychology, which viewed the patient as an isolated unit.

II. From Husserl to Heidegger: The Hermeneutic Turn

Heidegger was the student of Edmund Husserl, the father of Phenomenology. Husserl wanted to make philosophy a “rigorous science” by suspending judgment to look at pure consciousness. Heidegger rebelled.

- Husserl (Transcendental Phenomenology): “I want to step back and observe the world objectively.”

- Heidegger (Hermeneutic Phenomenology): “You cannot step back. You are already thrown into the world. You can only interpret (hermeneutics) from where you stand.”

This shift from “Describing” to “Interpreting” is vital for therapy. It means the therapist cannot be a “blank slate.” The therapist is a fellow Dasein, interpreting the client’s world while standing in their own.

III. Key Concepts for Psychotherapy and Trauma

1. Thrownness (Geworfenheit)

We do not choose our lives. We are “thrown” into a specific body, family, culture, and time. Trauma is often an experience of radical thrownness—realizing we are vulnerable and not in control. Healing involves catching the ball we were thrown (our facticity) and choosing how to throw it forward (projection).

2. Authenticity vs. The “They” (Das Man)

Most of the time, we live in “inauthenticity.” We do what “They” say, buy what “They” buy, and fear what “They” fear. We conform to avoid anxiety.

Authenticity (Eigentlichkeit) arises when we confront the anxiety of our own freedom. We realize, “I have to die my own death. Nobody can do it for me.” This confrontation pulls us out of the herd.

3. Anxiety (Angst) vs. Fear

Heidegger distinguishes between the two:

* Fear: Is about something specific (a spider, a gun, a boss).

* Anxiety: Is about nothing. It is the realization that the world has no inherent meaning and we are floating in a void.

For Heidegger, Anxiety is not a disorder; it is a teacher. It reveals our freedom. In therapy, we often try to medicate anxiety, but Heidegger suggests we must listen to it.

4. Conceptualizing Trauma: “World Collapse”

For Heidegger, our “World” is not the planet Earth; it is the web of meanings that holds us together. (e.g., “I am a safe person, my parents love me, the future is bright.”)

Trauma is the collapse of this World. When the web of meaning breaks (betrayal, violence), Dasein is left in the “Uncanny” (Unheimlich – literally “not-at-home”). The work of therapy is not just symptom reduction, but “World-Repair”—re-weaving a web of meaning that can hold the tragedy.

IV. The Shadow: Nazism and the Black Notebooks

We cannot discuss Heidegger without addressing the catastrophe of 1933. Heidegger joined the Nazi Party and became the Rector of Freiburg University. He gave speeches aligning his philosophy with the “Führer Principle.”

Even after the war, he remained largely silent about the Holocaust. His “Black Notebooks” (published recently) reveal a metaphysical antisemitism, where he viewed “World Jewry” as an agent of modern rootlessness and technological calculation.

The Problem for Philosophy: Can we use his tools if the architect was compromised?

Thinkers like Hannah Arendt (his former lover and student) and Paul Ricoeur argued that we can—and must—use Heidegger’s insights against his own politics. We use his critique of “The They” to critique the very totalitarianism he supported.

V. The Legacy: Who Did Heidegger Influence?

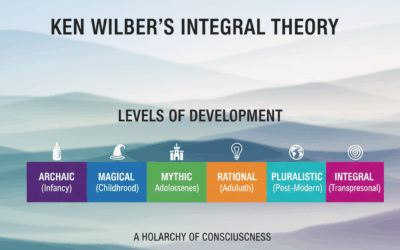

Heidegger’s thought triggered a chain reaction that split 20th-century philosophy.

1. The Existentialists

- Jean-Paul Sartre: Misread Heidegger creatively to create French Existentialism. Where Heidegger focused on Being, Sartre focused on political Freedom.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty: Took Heidegger’s “Being-in-the-world” and located it in the Body. This paved the way for Somatic Therapy.

2. The Frankfurt School (Critical Theory)

- Theodor Adorno: Hated Heidegger’s “Jargon of Authenticity.” He saw Heidegger’s language as a mystical cover for fascism. However, the Frankfurt School’s critique of technology (Instrumental Reason) is deeply indebted to Heidegger’s critique of technology.

- Walter Benjamin: Though ideologically opposed, Benjamin shared Heidegger’s sense of the “shattering” of tradition in modernity.

3. The Post-Structuralists

- Michel Foucault: “Heidegger was the essential philosopher… my entire development was determined by my reading of Heidegger.” Foucault applied Heidegger’s history of truth to the history of power.

- Jacques Lacan: Translated Heidegger’s work. Lacan’s concept of the “deficiency” of the subject mirrors Heidegger’s “Thrownness.”

- Gilles Deleuze: Took the concept of “Difference” and radicalized it, moving away from Heidegger’s nostalgia for “Being.”

4. The Hermeneutic Tradition

- Hans-Georg Gadamer: Heidegger’s student who softened the master’s radicalism into a philosophy of dialogue and understanding.

- Paul Ricoeur: Used Heidegger to analyze narrative identity and the nature of evil.

VI. Heidegger in the Therapy Room

How does this apply to a client sitting in front of you?

1. Daseinsanalysis (Medard Boss & Ludwig Binswanger):

This is the direct application of Heidegger to psychiatry. Instead of diagnosing “pathology,” the Daseinsanalyst asks: “How is this person restricting their openness to the world?” A depressed person has a “constricted world” where the future is blocked. The goal is to open the horizon of time again.

2. Focusing on “How” not “Why”:

Psychoanalysis asks “Why” (childhood causes). Heideggerian therapy asks “How” (phenomenological structure). “How are you experiencing this anxiety right now? Where do you feel your ‘thrownness’?”

3. The Technocratic Critique:

Heidegger warned that technology creates a “Standing Reserve” (Bestand)—treating nature and humans as resources to be used. In therapy, we resist the “Technological” view of the human (fixing a broken chemical machine) and restore the “Poetic” view (witnessing a unique unfolding of Being).

Philosophy and Depth Psychology Index

The Phenomenologists

- Edmund Husserl: The Father of Phenomenology

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty: The Embodied Mind

- Gaston Bachelard: The Poetics of Space

The Existentialists

- Jean-Paul Sartre: Freedom and Bad Faith

- Hannah Arendt: The Human Condition

- Arthur Schopenhauer: The Will to Live

- Friedrich Nietzsche: The Death of God

Critical Theory & Post-Structuralism

- Theodor Adorno: The Culture Industry

- Michel Foucault: Power and Subjectivity

- Slavoj Žižek: Ideology and the Real

- Ludwig Wittgenstein: Language Games

Heidegger’s Heirs in Hermeneutics

- Hans-Georg Gadamer: Fusion of Horizons

- Paul Ricoeur: Narrative Identity

- Peter Sloterdijk: Bubbles and Spheres

Bibliography

- Heidegger, M. (1927/1962). Being and Time. (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row.

- Heidegger, M. (1971). Poetry, Language, Thought. Harper & Row.

- Safranski, R. (1998). Martin Heidegger: Between Good and Evil. Harvard University Press.

- Boss, M. (1963). Psychoanalysis and Daseinsanalysis. Basic Books.

- Arendt, H. (1978). The Life of the Mind. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books.

0 Comments