Who was Socrates?

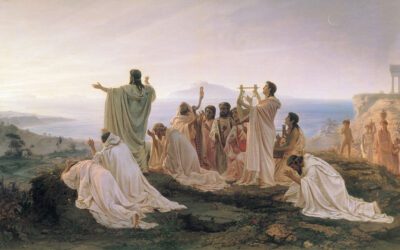

Socrates, one of the most influential figures in Western philosophy, was born in Athens, Greece, in 470 BCE. He lived during a time of great intellectual and cultural flourishing, known as the Golden Age of Athens. Socrates’ life and teachings had a profound impact on the development of Greek philosophy, and his influence can still be felt in the fields of ethics, epistemology, and metaphysics.

Socrates’ early life is shrouded in mystery, as he did not leave any written works of his own. Most of what we know about him comes from the writings of his students, particularly Plato and Xenophon. Socrates was the son of a stonemason and a midwife, and he served in the Athenian army during the Peloponnesian War. He was known for his unusual appearance, with a snub nose, protruding eyes, and a pot belly, and for his eccentric behavior, such as going barefoot and engaging in long, intense discussions with anyone who would listen.

Socrates’ philosophy was centered on the idea that the unexamined life is not worth living. He believed that the most important knowledge was self-knowledge and that the path to wisdom and virtue lay in questioning one’s own beliefs and assumptions. Socrates’ method of inquiry, known as the Socratic method or elenchus, involved engaging in dialogue with others and asking probing questions to expose the inconsistencies and limitations of their beliefs. Through this process, Socrates sought to help his interlocutors recognize their own ignorance and to encourage them to pursue truth and goodness.

One of the key concepts in Socratic philosophy is the idea of epistemic humility, or the recognition of the limits of one’s own knowledge. Socrates famously declared that he knew nothing, and he encouraged his followers to adopt a similar attitude of intellectual modesty. He believed that true wisdom consisted not in the accumulation of facts or the mastery of technical skills, but in the acknowledgment of one’s own ignorance and the willingness to question and examine one’s beliefs.

Another central theme in Socratic philosophy is the idea of ethical rationalism, or the belief that moral truths can be discovered through reason and argumentation. Socrates rejected the relativistic and skeptical views of the Sophists, who argued that truth and morality were subjective and conventional. Instead, he maintained that there were objective moral standards that could be known through philosophical inquiry and that the goal of the good life was to live in accordance with these standards.

Socrates’ ethical views were closely tied to his conception of the soul and its relation to the body. He believed that the soul was the seat of reason and the source of moral knowledge, while the body was a source of irrational desires and distractions. Socrates taught that the path to happiness and fulfillment lay in the cultivation of the soul through the pursuit of wisdom and virtue, rather than in the gratification of bodily pleasures or the acquisition of material wealth.

Socrates’ philosophy had a profound influence on his students, particularly Plato and Xenophon, who wrote extensively about their mentor’s life and teachings. Plato’s dialogues, in which Socrates is often the central figure, are among the most important sources of our knowledge of Socratic philosophy. In these dialogues, Socrates engages in discussions with various characters on topics such as justice, beauty, love, and the nature of knowledge, using his method of questioning and argumentation to expose the flaws in their reasoning and to point the way toward deeper understanding.

Plato’s own philosophy, which is characterized by his theory of Forms and his conception of the ideal state, is largely an extension and elaboration of Socratic ideas. Plato believed that the world of sense experience was an imperfect reflection of a higher realm of eternal, unchanging Forms, which could be known through reason and contemplation. He also developed a political philosophy based on the idea of the philosopher-king, a wise and virtuous ruler who would govern according to the principles of justice and the common good.

Aristotle, who was a student of Plato, was also influenced by Socrates, although he diverged from Plato’s philosophy in significant ways. Aristotle’s empirical approach to the study of nature and his emphasis on logical reasoning and classification of knowledge owe much to the Socratic method of inquiry. However, Aristotle rejected Plato’s theory of Forms and developed his own metaphysical and ethical theories based on the study of the natural world and the analysis of human behavior.

Socrates’ influence on Western philosophy and culture extends far beyond his immediate circle of students. His emphasis on critical thinking, logical argumentation, and the pursuit of knowledge through dialogue and debate laid the foundation for the development of modern academia and research. The Socratic method of questioning and examining assumptions is still widely used in educational settings to promote active learning and critical thinking skills.

However, Socrates himself might not have endorsed the modern academic system, which is often characterized by specialization, professionalization, and the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. Socrates believed that the ultimate goal of education was to cultivate virtue and to live a good life, rather than to acquire abstract knowledge or technical expertise. He saw philosophy not as a narrow academic discipline, but as a way of life that involved the constant examination of oneself and one’s beliefs in the pursuit of wisdom and truth.

Socrates’ legacy also extends to the field of depth psychology, particularly in the work of Carl Jung. Jung was deeply inspired by Socrates’ inner voice or daimonion, which he saw as a manifestation of the unconscious or the Self. Jung’s concept of the “Philemon,” an inner figure of wisdom and guidance, bears a striking resemblance to Socrates’ daimonion. Like Socrates, Jung believed that the path to self-knowledge and individuation involved engaging in dialogue with one’s inner voices and confronting the shadow aspects of the psyche.

The question of whether Socrates was an atheist is a matter of debate among scholars. While Socrates was critical of the traditional Greek gods and the myths associated with them, he also believed in the existence of a divine power or daimonion that guided his actions and provided him with moral insights. In Plato’s dialogues, Socrates often invokes the gods and speaks of his duty to follow the divine command, even at the cost of his own life. However, his conception of the divine was more abstract and philosophical than the anthropomorphic gods of Greek religion.

Socrates’ life and teachings continue to inspire and challenge us to this day. His commitment to the pursuit of truth, his willingness to question authority and convention, and his belief in the power of reason and dialogue to transform individuals and society remain as relevant as ever in our own time. As we grapple with the complex challenges of the modern world, Socrates’ example reminds us of the importance of critical thinking, ethical reflection, and the lifelong pursuit of wisdom and virtue.

Socrates Influence on Depth Psychology

Socrates’ influence on depth psychology, particularly in the work of Carl Jung, is significant and far-reaching. Jung, who founded the school of analytical psychology, was deeply inspired by Socrates’ inner voice or daimonion, which he saw as a manifestation of the unconscious or the Self. Jung believed that the path to self-knowledge and individuation involved engaging in dialogue with one’s inner voices and confronting the shadow aspects of the psyche, a process that bears a striking resemblance to Socrates’ method of self-examination and inquiry.

In Jung’s view, the figure of Socrates represented the archetypal image of the wise old man, a symbol of the Self or the inner guru that guides the individual toward wholeness and self-realization. Jung’s concept of the “Philemon,” an inner figure of wisdom and guidance that appeared to him in his own personal journey of individuation, was directly inspired by Socrates’ daimonion. Like Socrates, Jung believed that the path to psychological growth and spiritual awakening involved a willingness to confront one’s own ignorance and shadow, and to engage in a process of inner dialogue and self-discovery.

Moreover, Socrates’ emphasis on the importance of self-knowledge and the examination of one’s own beliefs and assumptions anticipates many of the key themes and practices of depth psychology. Socratic questioning, which involves a process of uncovering and challenging one’s underlying assumptions and beliefs, is a central technique in many forms of psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychoanalysis. The Socratic method of dialogue and inquiry, which emphasizes the importance of active listening, empathy, and the co-creation of meaning between therapist and client, is also a fundamental aspect of the therapeutic process in depth psychology.

Socrates’ influence on Western philosophy is equally profound and transformative. Prior to Socrates, the focus of Greek philosophy was primarily on cosmology and the study of the natural world. The Presocratic philosophers, such as Thales, Anaximander, and Heraclitus, sought to understand the basic principles and elements that governed the universe, and to explain the origins and nature of reality. While their contributions were significant and laid the foundation for later developments in science and philosophy, their approach was largely speculative and based on observation of the external world.

Socrates, in contrast, shifted the focus of philosophy inward, toward the study of human nature and the examination of moral and ethical questions. For Socrates, the most important knowledge was self-knowledge, and the unexamined life was not worth living. He believed that the path to wisdom and virtue lay in questioning one’s own beliefs and assumptions, and in engaging in dialogue with others to uncover the truth. Socrates’ method of inquiry, known as the elenchus or Socratic method, involved a process of questioning and cross-examination designed to expose the inconsistencies and limitations of his interlocutors’ beliefs and to lead them toward a deeper understanding of the truth.

Socrates’ emphasis on the importance of reason, logic, and critical thinking laid the foundation for the development of Western philosophy and science. His belief in the existence of objective moral truths that could be discovered through philosophical inquiry challenged the relativistic and skeptical views of the Sophists and paved the way for the development of ethical theories based on reason and argumentation. Socrates’ conception of the soul as the seat of reason and the source of moral knowledge also had a profound influence on later philosophers, particularly Plato and Aristotle, who developed their own theories of the soul and its relation to the body and the cosmos.

Moreover, Socrates’ method of dialogue and debate, which emphasized the importance of clear definitions, logical consistency, and the use of examples and analogies, became the model for philosophical discourse and argumentation in the Western tradition. The Socratic method of teaching, which involves a process of questioning and discussion designed to stimulate critical thinking and encourage students to arrive at their own conclusions, is still widely used in educational settings today.

In conclusion, Socrates’ influence on depth psychology and his transformation of Western philosophy cannot be overstated. His emphasis on self-knowledge, critical thinking, and the pursuit of wisdom and virtue through dialogue and inquiry laid the foundation for the development of psychotherapy and the modern conception of the self. At the same time, his shift in focus from cosmology to ethics and his belief in the existence of objective moral truths discoverable through reason and argumentation paved the way for the development of Western philosophy and science. Socrates’ legacy continues to inspire and challenge us to examine our own beliefs and assumptions, to engage in dialogue with others, and to pursue truth and goodness in all aspects of our lives.

Bibliography

Ahbel-Rappe, S., & Kamtekar, R. (Eds.). (2006). A Companion to Socrates. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Benson, H. H. (Ed.). (2011). A Companion to Plato. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Brickhouse, T. C., & Smith, N. D. (1994). Plato’s Socrates. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Guthrie, W. K. C. (1971). Socrates. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hadot, P. (1995). Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Irwin, T. (1995). Plato’s Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kahn, C. H. (1996). Plato and the Socratic Dialogue: The Philosophical Use of a Literary Form. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kraut, R. (Ed.). (1992). The Cambridge Companion to Plato. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McPherran, M. L. (1996). The Religion of Socrates. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Nails, D. (2002). The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company.

Nehamas, A. (1998). The Art of Living: Socratic Reflections from Plato to Foucault. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Prior, W. J. (1996). Virtue and Knowledge: An Introduction to Ancient Greek Ethics. London, UK: Routledge.

Reeve, C. D. C. (1989). Socrates in the Apology: An Essay on Plato’s Apology of Socrates. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company.

Reshotko, N. (2006). Socratic Virtue: Making the Best of the Neither-Good-Nor-Bad. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Santas, G. (1979). Socrates: Philosophy in Plato’s Early Dialogues. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Scott, G. A. (Ed.). (2002). Does Socrates Have a Method? Rethinking the Elenchus in Plato’s Dialogues and Beyond. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Tarrant, H. (2000). Plato’s First Interpreters. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Taylor, C. C. W. (1998). Socrates: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Vlastos, G. (1991). Socrates, Ironist and Moral Philosopher. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Waterfield, R. (2009). Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Philosophy

0 Comments