A Medieval Voice Speaking to Modern Minds

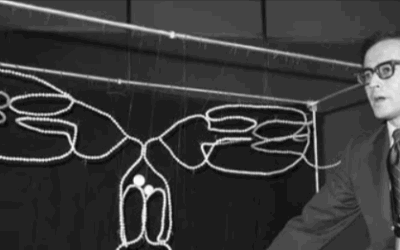

In the dimly lit scriptoriums of fourteenth-century England, a Franciscan friar bent over his manuscripts, crafting arguments that would reverberate through centuries of human thought. William of Ockham could not have known that his philosophical innovations would one day inform disciplines that did not yet exist—psychotherapy, depth psychology, and the scientific study of the human mind. Yet here we are, seven hundred years later, finding in his work a set of intellectual tools remarkably suited to the challenges of contemporary clinical practice.

Ockham is perhaps best known for the principle that bears his name: Ockham’s Razor, the methodological maxim that entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity, or as it is often rendered, the simplest explanation is usually the best. But to reduce Ockham to this single aphorism would be to miss the profound depth of his contributions to epistemology, metaphysics, and the philosophy of mind—contributions that speak with surprising directness to the work we do as therapists, analysts, and healers of the psyche.

This article explores how Ockham’s medieval insights illuminate contemporary psychotherapeutic practice, particularly within the framework of depth psychology. We will examine the historical circumstances that shaped his thought, trace the influence of his ideas across disciplines ranging from comparative religion to cognitive science, and consider why his voice continues to resonate across the ages.

Historical Context: The World That Made Ockham

To understand why Ockham wrote what he did, we must first understand the world in which he wrote. Born around 1287 in the village of Ockham in Surrey, England, William entered a Europe in flux. The medieval synthesis—that grand harmonization of Christian theology, Aristotelian philosophy, and institutional Church authority—was beginning to show cracks. The certainties of the High Middle Ages were giving way to questioning, doubt, and intellectual ferment.

Ockham entered the Franciscan order as a young man and pursued theological studies at Oxford, where he encountered the dominant philosophical tradition of his day: scholasticism. The scholastics, building on the work of Thomas Aquinas and others, had constructed elaborate metaphysical systems that sought to demonstrate the rational foundations of Christian faith. They populated their philosophical universe with a vast array of entities—universals, essences, substantial forms, and abstract entities of every description.

The scholastic approach reflected a broadly Platonic sensibility. Following Plato, many medieval thinkers held that universal concepts like “humanity,” “justice,” or “beauty” were not mere names or mental constructs but real entities existing independently of the particular things that instantiated them. A just action was just, they argued, because it participated in the universal Form of Justice. A human being was human because they shared in the essence of Humanity.

Ockham found this metaphysical profligacy deeply problematic. Why posit the existence of these invisible, intangible entities when simpler explanations were available? Why assume that every general term in our language corresponds to some entity in the world? The result of such thinking, Ockham believed, was a philosophy cluttered with unnecessary abstractions, a conceptual landscape so overgrown with theoretical entities that the actual world—the world of particular things and concrete experiences—became obscured.

The Political Storm

Ockham’s intellectual innovations did not unfold in an ivory tower. His life was marked by bitter conflict with ecclesiastical authority. In 1324, he was summoned to the papal court at Avignon to answer charges of heresy related to his theological writings. He spent four years there, under a cloud of suspicion, while a commission examined his work.

During this period, Ockham became embroiled in a separate controversy: the Franciscan poverty dispute. The Franciscans held that Christ and his apostles had owned no property, and that the Franciscan vow of absolute poverty was therefore the highest form of Christian life. Pope John XXII rejected this position, declaring it heretical. Ockham studied the papal pronouncements and concluded that the Pope himself had fallen into heresy.

In 1328, Ockham fled Avignon along with the Franciscan Minister General Michael of Cesena, eventually finding refuge at the court of Louis IV of Bavaria, who was locked in his own power struggle with the papacy. There Ockham remained for the rest of his life, writing prolifically on political philosophy, defending the autonomy of secular rulers against papal interference, and developing his arguments for the limits of papal authority.

This biographical context matters because it reveals something essential about Ockham’s intellectual temperament. He was not an abstract theorist spinning ideas in isolation. He was a man who challenged authority, who followed his reasoning even when it led to dangerous conclusions, and who paid dearly for his convictions. His philosophy bears the marks of this lived experience: a suspicion of unnecessary authority, a commitment to clear thinking over received tradition, and a recognition that intellectual courage sometimes requires personal sacrifice.

Why Parsimony Mattered

Ockham’s famous razor must be understood against this backdrop. The principle was not merely a logical tool; it was a weapon in a larger struggle against what Ockham saw as intellectual and institutional overreach. The elaborate metaphysical systems of the scholastics, with their proliferating entities and complex hierarchies, mirrored and supported the elaborate institutional hierarchies of the medieval Church. By challenging the former, Ockham was implicitly challenging the latter.

The razor cut in multiple directions. It cut against metaphysical abstractions that had no basis in experience. It cut against theological claims that exceeded the bounds of rational demonstration. And it cut against political theories that granted unlimited power to ecclesiastical authorities. Parsimony, for Ockham, was not just good methodology—it was a form of intellectual liberation.

Ockham’s Core Philosophical Contributions

Before exploring the applications of Ockham’s thought to psychotherapy, we must understand his key philosophical innovations in greater detail.

Nominalism and the Problem of Universals

At the heart of Ockham’s philosophy lies his nominalism—the position that only individual, particular things exist, and that universal terms are names (nomina) that we use to group similar particulars together. There is no “humanity” existing separately from individual human beings. There is no “redness” floating in some Platonic heaven, independent of red things. Universals are mental concepts, tools of thought and language, not features of extra-mental reality.

This may sound like a merely technical point in abstract metaphysics, but its implications are far-reaching. If universals are mental constructs rather than real entities, then the mind plays a more active role in organizing experience than the Platonic tradition had assumed. We do not passively receive universal Forms impressed upon us from without; we actively construct general concepts from our encounters with particulars. Knowledge becomes a collaborative activity between mind and world, not a one-way transmission from eternal truths to passive recipients.

Empiricism and the Primacy of Experience

Ockham’s nominalism led naturally to an emphasis on empirical knowledge—knowledge derived from experience of particular things. If there are no universal Forms to be grasped by pure intellect, then our knowledge of the world must come primarily through our senses, through our encounters with individual objects and events.

This empiricist tendency, while not fully developed in Ockham’s own work, would later be taken up and elaborated by philosophers like John Locke and David Hume. The modern scientific method, with its emphasis on observation, experiment, and the testing of theories against empirical evidence, has roots that can be traced back through this tradition to Ockham’s medieval innovations.

Epistemic Humility

Perhaps most importantly for our purposes, Ockham advocated a profound epistemic humility. He drew sharp distinctions between what could be known by reason, what could be known by faith, and what could not be known at all. He was skeptical of claims that exceeded the evidence, wary of grand systems that explained everything while predicting nothing, and attentive to the limits of human cognitive capacities.

This humility extended to theological matters. Ockham believed that many traditional “proofs” of God’s existence and attributes were logically flawed. Faith, he argued, was genuinely faith—a matter of trust and commitment that could not be reduced to rational demonstration. This separation of faith and reason would prove enormously influential, creating space for both genuine religious commitment and genuine scientific inquiry, each respected on its own terms.

The Razor in the Consulting Room: Ockham and Psychotherapeutic Practice

With this background in place, we can now explore the surprisingly rich connections between Ockham’s thought and contemporary psychotherapy. The relevance is not merely historical or analogical; Ockham’s principles speak directly to challenges that clinicians face every day.

Parsimony in Case Conceptualization

One of the most immediate applications of Ockham’s Razor lies in clinical case conceptualization. When a client presents with a complex array of symptoms, behaviors, and reported experiences, the therapist faces a fundamental interpretive challenge: How should this material be understood? What explanatory framework should be brought to bear?

The temptation—especially for theoretically sophisticated clinicians—is to construct elaborate explanations that account for every detail. A psychodynamic therapist might posit layers of unconscious conflict, defense mechanisms, object relations patterns, and transference dynamics, creating a rich but complex picture of the client’s inner world. A cognitive therapist might identify multiple cognitive distortions, core beliefs, intermediate assumptions, and automatic thought patterns. A systems-oriented therapist might map intricate webs of family dynamics, social influences, and cultural factors.

Ockham would counsel caution. Not because such complexity is never warranted, but because complexity should be earned, not assumed. Begin with the simplest explanation that accounts for the clinical phenomena. Add complexity only when simpler explanations prove inadequate. This is not a call for simplistic thinking; it is a call for disciplined thinking that justifies each additional explanatory entity.

In practice, this might mean starting with presenting problems before positing underlying pathology, attending to what the client actually says before interpreting what they really mean, and considering situational factors before invoking characterological explanations. The parsimonious clinician is not lacking in depth but is rather skeptical of unearned depth, preferring genuine understanding to theoretical elaboration.

The Nominalist Challenge to Diagnostic Categories

Ockham’s nominalism raises provocative questions about the status of psychiatric diagnoses. When we say that a client has “depression” or “borderline personality disorder” or “complex PTSD,” what exactly are we claiming? Are these real entities—natural kinds that exist independently of our classification schemes? Or are they names, useful categories that we have constructed to group together similar patterns of distress and dysfunction?

The nominalist perspective suggests the latter. Diagnostic categories are tools, not discoveries. They are ways of organizing clinical phenomena that may be more or less useful for various purposes—communication among professionals, research, treatment planning, insurance billing—but they do not carve nature at its joints. The map is not the territory.

This perspective has significant clinical implications. If diagnoses are constructs rather than realities, then we should hold them lightly, recognizing their utility without reifying them. We should remain attentive to the particular individual before us, whose suffering will never be fully captured by any diagnostic label. And we should be open to revising our conceptualizations as new information emerges, rather than forcing recalcitrant data into predetermined categories.

The nominalist approach aligns well with person-centered and humanistic traditions in psychotherapy, which have long emphasized the unique particularity of each client. It also resonates with contemporary critiques of the DSM and similar classification systems, which have been accused of medicalizing normal human variation, pathologizing distress that might be better understood as appropriate responses to difficult circumstances, and obscuring more than they reveal about individual clients.

Epistemic Humility in Therapeutic Interpretation

Depth psychology, in its various forms, involves the interpretation of psychological material—dreams, fantasies, symptoms, slips of the tongue, patterns of relating. The analyst or depth-oriented therapist listens for what lies beneath the surface, attending to unconscious meanings, symbolic communications, and hidden dynamics.

This interpretive activity is essential to depth work, but it carries significant risks. The therapist may see patterns that are not there, impose theoretical preconceptions on ambiguous material, or mistake their own projections for insights into the client’s psyche. The history of depth psychology includes cautionary tales of analysts who became so confident in their interpretive schemes that they could explain everything—and therefore, arguably, explained nothing.

Ockham’s epistemic humility offers a corrective. The depth-oriented clinician should remain genuinely uncertain about unconscious meanings, offering interpretations tentatively rather than pronouncing them authoritatively. They should seek corroboration from the client’s response, attending carefully to whether interpretations open up new understanding or merely shut down exploration. And they should maintain a skeptical attitude toward their own theoretical frameworks, recognizing that these are lenses that illuminate certain features while inevitably obscuring others.

This humility is not incompatible with clinical confidence; indeed, it is a more mature form of confidence, one that acknowledges the limits of knowing while still engaging fully in the therapeutic endeavor. The humble interpreter says not “I know what this means” but “Here is what this might mean; let us explore together.”

The Razor Applied to Theoretical Pluralism

Contemporary psychotherapy is characterized by theoretical pluralism—a proliferation of schools, approaches, and techniques, each with its own conceptual vocabulary and clinical methods. Psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, humanistic, existential, systemic, somatic, transpersonal: the list goes on and on, with new approaches emerging regularly.

From an Ockhamist perspective, this proliferation raises questions. How many of these theoretical entities are truly necessary? To what extent do different schools describe the same phenomena in different languages versus genuinely different phenomena? Are the competing explanatory frameworks genuinely incompatible, or might they be viewed as complementary perspectives on a common subject matter?

The parsimonious approach would seek to identify the core mechanisms of therapeutic change that operate across different modalities, stripping away theoretical accretions to find the essential elements. Research on common factors in psychotherapy represents one attempt at such parsimony, suggesting that variables like the therapeutic alliance, client expectation, and therapist allegiance may account for more of the variance in outcomes than the specific techniques associated with particular schools.

This does not mean that all approaches are equally effective for all conditions, or that theoretical specificity is never valuable. But it does suggest that we should be cautious about multiplying therapeutic entities beyond necessity, and that the simplest explanation for why therapy works may not be the most theoretically elaborate one.

Ockham in Comparative Religion and Philosophy

Ockham’s influence extends far beyond psychology into comparative religion, philosophy of science, and numerous other disciplines. Understanding these broader applications enriches our appreciation of his thought and reveals additional connections to depth psychological themes.

The Separation of Faith and Reason

Ockham’s sharp distinction between faith and reason had profound implications for religious thought. By arguing that many theological claims could not be rationally demonstrated, Ockham created space for a form of religious faith that did not depend on philosophical proofs. Faith became a matter of will and trust, a leap made in the face of uncertainty rather than a conclusion reached through syllogistic reasoning.

This position influenced later developments in both Protestant and Catholic theology. Luther’s emphasis on faith alone (sola fide) has Ockhamist resonances, as does the fideist tradition that regards religious belief as beyond the reach of rational evaluation. In comparative religious studies, Ockham’s approach allows for taking diverse religious traditions seriously on their own terms, without demanding that they conform to a single rational standard.

For depth psychology, this separation is significant because it allows for a nuanced engagement with religious and spiritual material in therapy. The Ockhamist clinician can take a client’s religious faith seriously without requiring that it be rationally justified, recognizing that faith operates according to its own logic, not reducible to empirical or scientific reasoning. This creates space for exploring spiritual dimensions of experience without either dismissing them as irrational or demanding that they meet criteria they were never meant to satisfy.

Voluntarism and Divine Freedom

Ockham’s theology emphasized divine voluntarism—the primacy of God’s will over God’s intellect. God did not create the world according to pre-existing rational principles that constrained divine choice; rather, God freely willed the world into existence, and whatever principles govern creation are themselves products of that free choice.

This position had important implications for the philosophy of science. If the structure of the world is the product of free divine choice rather than rational necessity, then we cannot deduce what the world is like from first principles. We must look and see—engage in empirical investigation—because there is no way to know in advance what God has chosen to create.

The voluntarist emphasis on freedom and will also connects to existentialist themes that would emerge centuries later. Jean-Paul Sartre’s emphasis on radical freedom and the priority of existence over essence has Ockhamist antecedents, as does the existentialist rejection of universal human nature in favor of individual self-creation.

In depth psychology, these themes resonate with approaches that emphasize human agency, choice, and the capacity for self-determination. The Ockhamist perspective supports therapeutic approaches that help clients recognize and exercise their freedom, rather than understanding them as passive products of determining forces—whether those forces are conceived as instinctual drives, cognitive schemas, or systemic dynamics.

Political Philosophy and Institutional Critique

Ockham’s political writings, produced during his exile at the Bavarian court, developed sophisticated arguments for limiting papal authority and defending the autonomy of secular rulers. He argued that political authority did not derive from the Church but had its own legitimate foundations, and that the Pope’s jurisdiction was properly limited to spiritual matters.

These arguments contributed to the gradual differentiation of religious and secular authority that characterizes modern Western societies. They also reflect Ockham’s broader tendency to challenge institutional overreach and defend spaces of autonomy against centralizing powers.

For psychotherapy, this aspect of Ockham’s thought is relevant in several ways. It supports the therapist’s appropriate skepticism toward institutional orthodoxies, whether these take the form of diagnostic manuals, treatment guidelines, or professional credentialing requirements. It encourages a questioning attitude toward any authority that claims more than it can legitimately deliver. And it reminds us that the therapeutic relationship, at its best, is a space of freedom where both therapist and client can think for themselves, unconstrained by external demands that do not serve the healing process.

Why Ockham Speaks Across the Ages

The enduring relevance of Ockham’s thought is not accidental. His ideas address perennial features of human cognition and social organization that recur across different historical periods and cultural contexts.

The Perennial Temptation of Over-Systematization

Human beings are pattern-seekers. We find it deeply satisfying to construct comprehensive explanatory systems that tie together diverse phenomena under unifying principles. This drive has produced some of humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements, from Newtonian physics to Darwinian evolution.

But the drive to systematize can also lead us astray. We can mistake the elegance of our theories for evidence of their truth. We can become so attached to our explanatory frameworks that we ignore or explain away disconfirming evidence. We can populate our theoretical universes with entities that serve no function except to make our theories seem more complete.

Ockham’s razor is a perennial corrective to this tendency. Each generation needs to be reminded that complexity is not the same as depth, that theoretical sophistication can mask empirical emptiness, and that the best explanation is often not the most elaborate one. This is as true in contemporary psychology as it was in medieval scholasticism.

The Value of Intellectual Courage

Ockham’s willingness to follow his reasoning wherever it led—even when it brought him into conflict with the most powerful institution of his age—speaks to a timeless human need for intellectual courage. Every society has its orthodoxies, its received wisdoms that are not to be questioned. Every professional field has its established authorities, its canonical texts, its gatekeepers who determine what counts as legitimate knowledge.

The Ockhamist spirit challenges us to think for ourselves, to evaluate claims on their merits rather than their sources, and to accept the costs of honest inquiry. In psychotherapy, this might mean questioning therapeutic approaches that have become fashionable without adequate evidence, challenging diagnostic categories that serve institutional interests more than clinical needs, or acknowledging the limits of our knowledge in a field that often rewards confident pronouncement.

The Balance of Humility and Engagement

Perhaps most importantly, Ockham models a form of intellectual engagement that combines genuine humility with genuine commitment. He was not a skeptic who doubted everything; he was a thinker who tried to believe only what the evidence warranted. He was not a relativist who regarded all views as equally valid; he was a philosopher who argued vigorously for positions he believed to be correct. But he held his positions with an awareness of fallibility, a recognition that even carefully reasoned conclusions might be wrong.

This balance is essential for psychotherapeutic practice. We must act—we must make clinical judgments, offer interpretations, choose interventions—even though we cannot be certain we are right. The Ockhamist clinician acts with full engagement while holding their certainties lightly, remaining genuinely open to being wrong and genuinely willing to revise their views in light of new evidence.

The Razor’s Edge

William of Ockham died around 1347, likely a victim of the Black Death that was devastating Europe. He did not live to see the Renaissance, the Reformation, or the Scientific Revolution—transformations of Western culture that his ideas had helped to make possible. He could not have imagined psychoanalysis, cognitive neuroscience, or the therapeutic professions that now number millions of practitioners worldwide.

Yet his thought remains alive because it addresses challenges that did not end with the fourteenth century. We still construct elaborate theoretical systems that may obscure more than they reveal. We still face authorities that claim more than they can deliver. We still struggle to balance epistemic humility with the demands of practical action.

For depth psychology and psychotherapy, Ockham offers not a set of specific techniques but something more valuable: a stance, an orientation, a way of approaching the complexities of human suffering and human healing. It is a stance that values parsimony without sacrificing depth, that embraces uncertainty without abandoning commitment, and that challenges authority without rejecting wisdom.

The razor’s edge is narrow, but it is the only path to genuine understanding. Seven centuries after Ockham first articulated his principles, we are still learning to walk it.

0 Comments