Why Understanding the Architecture of Mind Matters for Therapy

Before we explore the life and revolutionary work of Bernard Baars, we need to understand why his ideas matter so profoundly for anyone working in the healing professions. Baars did not merely propose a theory of consciousness. He created a framework for understanding how the mind organizes itself, how information flows between conscious and unconscious processes, and why certain experiences capture our awareness while others remain forever hidden in the shadows.

For therapists, this framework provides something invaluable. It provides a map of the territory we are trying to navigate.

Consider what happens in a therapy session. A client sits before you, struggling to articulate something they cannot quite grasp. They sense that something is wrong, that some pattern keeps repeating in their life, that certain feelings emerge unbidden and overwhelm them. But they cannot see the source. They cannot understand why they react the way they do, why certain situations trigger them, why their own minds seem to work against them.

What is happening in such moments? From a purely psychological perspective, we might speak of defenses, of repression, of unconscious conflicts. But these terms, however clinically useful, remain somewhat abstract. They describe what is happening without explaining how it happens, without grounding the phenomena in the actual machinery of the brain and mind.

Bernard Baars spent his career building that grounding. His Global Workspace Theory describes the cognitive architecture that underlies conscious experience. It explains why consciousness is limited, why we can only hold a few things in mind at once, why attention functions like a spotlight illuminating some things while leaving others in darkness. And it explains how this architecture can break down, how trauma can disrupt the normal flow of information into awareness, how certain experiences can become stuck outside the global workspace where they continue to influence behavior without ever reaching consciousness.

For clinicians working with trauma, dissociation, and other disorders of awareness, Baars’s framework offers a way to understand what we are actually trying to accomplish in therapy. We are trying to help information that has been trapped outside awareness to finally enter the global workspace. We are trying to restore the normal broadcasting function that allows experiences to be integrated with the rest of the person’s mental life.

This is not merely an academic point. It changes how we think about therapeutic interventions. It helps us understand why certain techniques work and others fail. And it suggests new approaches that target the specific cognitive mechanisms involved in conscious access.

Understanding Baars’s work will make you a better therapist. Not because it provides easy answers or simple techniques, but because it deepens your understanding of the mind you are trying to help heal.

The Philosophical Origins of a Scientific Quest

Bernard J. Baars was born in 1946 in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. He came of age in a postwar Europe still rebuilding itself, in a intellectual culture shaped by the phenomenological tradition that had flourished in continental philosophy. This background would prove important. While American behaviorism dismissed consciousness as unscientific and beyond study, European thinkers had never fully abandoned the investigation of subjective experience.

Baars eventually moved to the United States, where he would earn his PhD in Psychology from UCLA in 1977. But he carried with him a conviction that consciousness was a legitimate topic for scientific investigation, even when this position was deeply unfashionable in American academic psychology.

At the time Baars began his career, behaviorism still cast a long shadow over psychology. The dominant view held that science should concern itself only with observable behavior, that mental states were either illusory or irrelevant, and that any talk of consciousness was merely folk psychology destined to be replaced by proper neuroscience. Many researchers who were privately interested in consciousness kept quiet about it, fearing damage to their careers.

Baars was not quiet. He insisted that consciousness was not only real but scientifically tractable. He argued that we could study conscious experience rigorously by comparing it systematically with unconscious processes. If we could identify what distinguished conscious from unconscious mental events, we might discover the functional architecture underlying awareness.

This methodological insight, which Baars called “contrastive analysis,” became the foundation of his research program. Rather than trying to define consciousness philosophically or reduce it immediately to neural mechanisms, Baars proposed gathering empirical evidence about the differences between conscious and unconscious processing. What can you do with conscious information that you cannot do with unconscious information? What happens in the brain when information enters awareness versus when it remains subliminal? These were questions that could be addressed experimentally.

From Freudian Slips to Cognitive Architecture

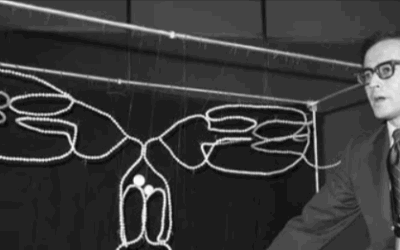

Baars’s early research focused on what might seem an unlikely topic for a consciousness scientist. He studied errors. Slips of the tongue. Mistakes in action. The kinds of blunders that Sigmund Freud had famously interpreted as windows into the unconscious mind.

Working at Stony Brook University in New York, Baars and his colleagues developed methods for inducing predictable speech errors in the laboratory. They could create conditions where subjects would reliably produce spoonerisms or other verbal slips, and they could study the cognitive mechanisms underlying these errors.

This research proved remarkably productive. It revealed that speech production involves a kind of editing process that monitors planned utterances before they are spoken. Most potential errors are caught and corrected before they escape our lips. But sometimes the editing fails, and the error slips through.

What determined whether errors were caught or missed? Baars found that attention played a crucial role. When attention was directed elsewhere, errors were more likely to escape. The editing process required conscious monitoring to function effectively.

This finding suggested something important about the relationship between consciousness and cognitive control. Consciousness seemed to be involved in coordinating and monitoring complex behaviors. When consciousness was occupied elsewhere, the monitoring failed and errors occurred.

But there was more. Baars and his colleagues found that errors were not random. They showed systematic patterns that revealed the structure of the speech production system. And some of those patterns seemed to reflect unconscious motivational factors, just as Freud had suggested. Under certain conditions, subjects were more likely to produce taboo words or emotionally charged errors.

This early research convinced Baars that consciousness was not an epiphenomenon or an illusion but a functional component of the cognitive system with real causal effects on behavior. The challenge was to understand what role it played and how it was implemented in the brain.

The Theater of the Mind

In 1988, Baars published his landmark book A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. The book proposed what would become known as Global Workspace Theory, a framework that would influence virtually all subsequent scientific research on consciousness.

The theory began with a puzzle. How does a unified stream of conscious experience emerge from a brain that is massively parallel, distributed, and largely unconscious?

The brain contains billions of neurons organized into countless specialized systems. One system processes color. Another handles motion. Others recognize faces, parse grammar, coordinate movement, regulate emotion. These systems operate simultaneously and largely independently. Most of their activity never reaches awareness.

Yet conscious experience feels unified. We do not experience the world as a jumble of separate features but as coherent scenes populated by recognizable objects and meaningful events. Somehow the brain integrates the outputs of its many specialized systems into a single stream of awareness.

How does this happen?

Baars found his answer in an unexpected place. In the field of artificial intelligence, researchers had developed systems called “blackboard architectures.” These were programs that solved complex problems by allowing many specialized modules to share information through a common workspace or “blackboard.” Each module was an expert in some narrow domain, but by posting their outputs to the shared workspace, they could cooperate to solve problems that none could solve alone.

Baars proposed that the brain works similarly. He called his version of this idea the Global Workspace. The Global Workspace is a functional hub that allows information to be broadcast widely across the brain. When information enters the Global Workspace, it becomes available to many different cognitive systems simultaneously. This widespread availability is what we experience as consciousness.

To make the theory more intuitive, Baars developed an extended metaphor. He described the mind as a theater. On the stage of this theater, conscious experience unfolds. A spotlight of attention illuminates whatever is currently in awareness. The rest of the stage remains in darkness, ready to receive the spotlight but currently unconscious.

But the stage is only a small part of the theater. Behind the stage, invisible to the audience, are the many systems that shape what appears onstage. There are stagehands moving scenery, directors making decisions, playwrights crafting the script. These are the unconscious processes that influence conscious experience without themselves being conscious.

And in the audience sit countless specialized systems that receive the broadcast from the stage. When something appears in the spotlight, the entire audience sees it. This is the global broadcast that makes conscious information available throughout the brain.

The theater metaphor was explicitly not meant to imply a “Cartesian theater” where a little homunculus sits watching the show. Baars was careful to distance himself from this interpretation, which philosophers like Daniel Dennett had criticized. There is no single place in the brain where consciousness “comes together.” Instead, the Global Workspace is a dynamic process of broadcasting and integration that emerges from the coordinated activity of many brain regions.

The Functions of Consciousness

Global Workspace Theory was not merely a description of conscious experience but a functional theory. It claimed to explain why we have consciousness, what it does for us, what its biological purpose is.

According to Baars, consciousness serves several crucial functions.

First, consciousness enables global access. When information enters the Global Workspace, it becomes available to many different systems that would otherwise have no access to it. Perceptual systems can communicate with memory systems. Motor systems can access the outputs of planning systems. The Global Workspace breaks down the barriers between specialized modules and allows information to flow freely.

Second, consciousness enables recruitment. When we face a novel problem, we need to mobilize the right combination of cognitive resources. We need to bring together relevant memories, perceptual skills, and motor programs. The Global Workspace provides a mechanism for this recruitment. By broadcasting information globally, it allows relevant systems to recognize that their expertise is needed and to participate in solving the problem.

Third, consciousness enables learning. Baars argued that new learning requires conscious attention. We can learn unconsciously about regularities in our environment, but to form new intentional associations, to update our beliefs, to modify our behavior based on feedback, we need consciousness. The Global Workspace is where learning happens.

Fourth, consciousness enables integration. The many specialized systems of the brain are constantly producing their own local representations. But to understand the world and act effectively in it, we need to integrate these separate representations into a coherent whole. The Global Workspace provides the venue for this integration.

These functions help explain why consciousness is so limited. We can only be conscious of a few things at once, roughly the famous “seven plus or minus two” items that can be held in working memory. This seems like a severe limitation for a brain of a hundred billion neurons.

But Baars argued that the limitation is a feature, not a bug. If everything were conscious, nothing would stand out. The limited capacity of consciousness creates a bottleneck that forces information to compete for access. Only the most relevant, most important, most urgent information wins the competition and enters awareness. Everything else is processed unconsciously, efficiently, automatically.

This competitive architecture ensures that consciousness contains what we most need to know at any given moment. The spotlight of attention is drawn to threats, opportunities, novelties, and problems that require deliberate thought. Routine processing can continue in the background without burdening awareness.

The Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness

Baars did not work alone. Recognizing that the scientific study of consciousness required a community of researchers, he became one of the founders of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness in 1994. This organization brought together neuroscientists, psychologists, philosophers, and others interested in understanding the neural and cognitive basis of conscious experience.

The Association holds annual conferences that have become the premier venue for consciousness research. It provides a forum where researchers from different disciplines can share findings, debate theories, and collaborate on new projects. The existence of such an organization may seem unremarkable today, but in the mid-1990s, when consciousness was still somewhat taboo in scientific circles, creating such a community was a significant achievement.

Baars also co-founded the journal Consciousness and Cognition with William P. Banks. He served as editor of this journal for more than fifteen years, helping to establish the standards and practices for scientific research on consciousness. The journal became a primary outlet for empirical research on conscious and unconscious processes.

Through these institutional contributions, Baars helped transform consciousness from a topic that scientists discussed only in private to a legitimate field of scientific inquiry with its own professional organizations, journals, and research programs.

From Theory to Neuroscience

Global Workspace Theory began as a cognitive theory, describing the functional architecture of consciousness without specifying how that architecture was implemented in the brain. But Baars always intended the theory to connect with neuroscience, and over time, those connections became increasingly clear.

One key connection involved the prefrontal cortex. Baars proposed that the Global Workspace was associated with a network of long-range connections linking the prefrontal cortex to other brain regions. The prefrontal cortex, with its dense reciprocal connections to virtually every other cortical area, seemed well suited to serve as a hub for global integration and broadcasting.

Brain imaging studies began to confirm this picture. When subjects became conscious of a stimulus, there was increased activation in a network that included the prefrontal and parietal cortices. This activation is accompanied by increased long-range synchronization between distant brain regions, as if neurons throughout the brain were suddenly singing together.

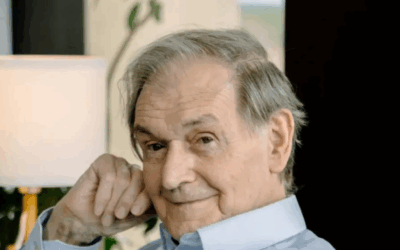

Baars spent about ten years as a Senior Fellow at the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla, California, working with Nobel laureate Gerald Edelman. Edelman had developed his own theory of consciousness, Neural Darwinism, which emphasized the role of reentrant connections between brain regions. The collaboration allowed Baars to enrich Global Workspace Theory with insights from Edelman’s neurobiological perspective.

In 2019, Baars received the Hermann von Helmholtz Life Contribution Award from the International Neural Network Society, recognizing his paradigm-changing contributions to the science of perception and consciousness.

The LIDA Cognitive Architecture

One of the most significant developments of Global Workspace Theory has been its computational implementation in the LIDA cognitive architecture, developed by Baars’s longtime collaborator Stan Franklin at the University of Memphis.

LIDA stands for Learning Intelligent Distribution Agent. It is a software system that implements the principles of Global Workspace Theory in a working computational model. The system has unconscious processes that compete for access to a global workspace. When information wins this competition, it is broadcast to other components of the system. The system can learn, form memories, and generate behavior based on the information it becomes “conscious” of.

LIDA demonstrates that the concepts of Global Workspace Theory are computationally coherent. They can be implemented in actual software that performs cognitive tasks. This provides a kind of existence proof for the theory, showing that its mechanisms can actually work.

The LIDA project has also generated new theoretical insights. By trying to implement the theory computationally, Franklin and Baars were forced to specify details that the original theory left vague. This led to refinements and extensions of the theory that have been published in numerous joint papers.

The collaboration between Baars and Franklin represents a model for how theoretical and computational work can proceed together, each informing and constraining the other.

The Dehaene-Changeux Extension

While Baars was developing Global Workspace Theory in the United States, Stanislas Dehaene and Jean-Pierre Changeux in Paris were developing a neurobiological version of similar ideas. Their Global Neuronal Workspace model built explicitly on Baars’s cognitive theory but specified in detail how the workspace might be implemented in the brain.

Dehaene and Changeux proposed that the Global Workspace corresponds to a network of neurons with long-range axons that connect distant brain regions. These “workspace neurons” are concentrated in the prefrontal and parietal cortices. When information from a sensory module reaches sufficient intensity, it triggers a sudden “ignition” of the workspace network. This ignition corresponds to the moment of conscious awareness.

The Dehaene-Changeux model made specific predictions that could be tested with brain imaging and electrophysiology. Conscious perception should be associated with late, widespread activation involving prefrontal and parietal regions. There should be a sharp threshold separating conscious from unconscious processing, corresponding to the all-or-none nature of ignition.

These predictions have been largely confirmed. The collaboration between the cognitive theory of Baars and the neurobiological theory of Dehaene and Changeux represents one of the most successful examples of theory development in consciousness science.

Baars has always been generous in acknowledging this collaboration and in recognizing that the neural implementation of the Global Workspace represents a crucial extension of his original ideas.

What Global Workspace Theory Teaches Us About Trauma

For clinicians working with trauma survivors, Global Workspace Theory offers profound insights into the nature of traumatic experience and its treatment.

Consider what happens during a traumatic event. The person is overwhelmed by stimuli, by threat, by terror. The normal processes of conscious integration are disrupted. Information is processed by specialized systems but may never reach the Global Workspace where it could be integrated with the person’s ongoing narrative, their sense of self, their understanding of the world.

This provides a framework for understanding traumatic memory. Traumatic experiences may be encoded in sensory and emotional systems without ever becoming fully conscious in the sense of entering the Global Workspace. The information exists, it influences behavior and emotion, but it remains outside the integrated stream of awareness.

This is precisely what trauma survivors describe. They have flashbacks, sensory intrusions that seem to bypass normal consciousness and deliver raw perceptual experience directly. They have emotional reactions that seem disconnected from any recognizable thought or memory. They have bodily sensations that appear without explanation. These fragments of traumatic experience have never been integrated into the Global Workspace.

Dissociation can be understood as a more severe disruption of Global Workspace function. In dissociative states, the normal broadcasting and integration that consciousness provides breaks down. Different aspects of experience may be processed in parallel without ever coming together in unified awareness. The person may feel disconnected from their body, from their emotions, from their sense of self.

From this perspective, effective trauma therapy must somehow restore Global Workspace function. It must help traumatic information finally enter the integrated stream of awareness where it can be connected with narrative memory, reflected upon, and assimilated into the person’s understanding of their life.

Baars himself addressed these clinical applications in his 1997 book In the Theater of Consciousness, which included discussions of hypnosis, absorbed states of mind, and adaptation to trauma. He recognized that the theater metaphor could illuminate not only normal conscious experience but also the various ways that experience can go wrong.

The therapeutic relationship itself can be understood through this lens. The therapist provides a stable context, what Baars might call a “scene setter,” that supports the client’s conscious processing. The therapist’s attention helps direct the client’s spotlight toward material that needs to be brought into awareness. The therapeutic conversation provides a format for broadcasting traumatic information to other cognitive systems where it can be integrated.

Techniques like EMDR and Brainspotting can be understood as methods for facilitating access to the Global Workspace. By engaging the attentional system while simultaneously accessing traumatic material, these techniques may help information that has been stuck outside awareness finally enter the integrated stream of consciousness.

Somatic approaches work with bodily sensations that may represent traumatic information encoded in motor and interoceptive systems. By bringing these sensations into focused awareness, somatic therapy helps them enter the Global Workspace where they can be integrated with other aspects of experience.

The limited capacity of the Global Workspace also has clinical implications. If we can only be conscious of a few things at once, then overwhelming trauma may simply exceed the system’s capacity. Titration, the practice of working with small amounts of traumatic material at a time, makes sense as a way of keeping the load within what the Global Workspace can handle.

Major Publications and Contributions

Bernard Baars has authored over 200 scientific articles, chapters, and books that have shaped our understanding of consciousness and cognition.

His 1988 book A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness presented the first comprehensive statement of Global Workspace Theory and established Baars as a leading figure in consciousness research. Daniel Dennett wrote that for those who want to model consciousness, this book is “the starting line.”

His 1986 edited volume The Cognitive Revolution in Psychology documented the paradigm shift from behaviorism to cognitive science, placing the study of consciousness in broader historical context.

His 1992 edited volume Experimental Slips and Human Error: Exploring the Architecture of Volition collected research on speech errors and action slips, demonstrating how the study of mistakes can illuminate the normal functioning of mind.

His 1997 book In the Theater of Consciousness: The Workspace of the Mind presented Global Workspace Theory for a general audience using the extended theater metaphor. The book made the science of consciousness accessible to readers without technical backgrounds and has been widely praised for its clarity and insight.

His 2010 textbook Cognition, Brain and Consciousness: Introduction to Cognitive Neuroscience, co-authored with Nicole Gage, became a standard text for introducing students to the field.

His 2019 book On Consciousness: Science and Subjectivity collected his major writings on Global Workspace Theory with updates reflecting the most recent developments.

Throughout his career, Baars has collaborated with Stan Franklin on papers developing the computational implementation of Global Workspace Theory in the LIDA architecture. These papers have appeared in venues including the International Journal of Machine Consciousness.

A Timeline of Life and Work

1946 Born in Amsterdam, Netherlands

1977 Completes PhD in Psychology at UCLA

1977-1988 Professor of Psychology at State University of New York, Stony Brook, conducting research on speech errors and the Freudian slip

1983 Publishes first papers on contrastive analysis and the global workspace concept

1986 Publishes The Cognitive Revolution in Psychology

1988 Publishes A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness, the foundational statement of Global Workspace Theory

1992 Publishes edited volume Experimental Slips and Human Error

1994 Co-founds the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness

1994 Co-founds the journal Consciousness and Cognition with William P. Banks

1997 Publishes In the Theater of Consciousness: The Workspace of the Mind

Late 1990s-2000s Serves as Senior Fellow in Theoretical Neurobiology at the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla, California, working with Gerald Edelman

2005 Publishes major paper “Global workspace theory of consciousness: Toward a cognitive neuroscience of human experience” in Progress in Brain Research

2009 Publishes “Consciousness is computational: The LIDA model of global workspace theory” with Stan Franklin

2010 Publishes textbook Cognition, Brain and Consciousness with Nicole Gage

2019 Receives Hermann von Helmholtz Life Contribution Award from International Neural Network Society

2019 Publishes On Consciousness: Science and Subjectivity

Present Continues as Senior Distinguished Fellow at Center for the Future Mind, Florida Atlantic University, and affiliated fellow at the Neurosciences Institute

The Continuing Legacy

Bernard Baars’s Global Workspace Theory has become one of the most influential frameworks in consciousness science. It has inspired decades of empirical research, computational modeling, and theoretical development. It has been extended and refined by researchers around the world, including Stanislas Dehaene’s Global Neuronal Workspace model and Stan Franklin’s LIDA cognitive architecture.

But perhaps more importantly, Baars helped make the scientific study of consciousness respectable. When he began his career, consciousness was taboo. By the time he received the Helmholtz Award, consciousness had become one of the most exciting frontiers of neuroscience. Baars played a crucial role in that transformation, not only through his theoretical contributions but through his institution-building, his mentoring, and his tireless advocacy for the scientific investigation of subjective experience.

For therapists, Baars’s work provides a framework for understanding the cognitive architecture underlying awareness, attention, and integration. It explains why consciousness is limited, why attention matters, why certain experiences remain unconscious, and how the normal processes of awareness can be disrupted by trauma and restored by effective treatment.

We are still far from a complete understanding of consciousness. But thanks to Bernard Baars, we have a map to guide our exploration. We understand that consciousness involves a global workspace where information is broadcast and integrated. We understand that attention functions as a spotlight directing what enters this workspace. We understand that the architecture of consciousness has real implications for understanding the disorders that bring people to therapy.

This understanding does not replace clinical skill or therapeutic presence. But it grounds our work in a scientific framework that makes the art of therapy more effective and more comprehensible. And for that, Bernard Baars deserves our gratitude.

Want to learn more about how cognitive science informs trauma therapy? Contact GetTherapyBirmingham.com to explore brain-based approaches to healing.

Bibliography

Primary Sources by Bernard Baars

Baars, B.J. (1988). A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Preview available at: https://books.google.com/books/about/A_Cognitive_Theory_of_Consciousness.html

Baars, B.J. (1986). The Cognitive Revolution in Psychology. New York: Guilford Press.

Baars, B.J. (Ed.). (1992). Experimental Slips and Human Error: Exploring the Architecture of Volition. New York: Springer. Available at: https://www.springer.com/us/book/9780306438660

Baars, B.J. (1997). In the Theater of Consciousness: The Workspace of the Mind. New York: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/in-the-theater-of-consciousness-9780195102659

Baars, B.J., & Gage, N.M. (2010). Cognition, Brain and Consciousness: Introduction to Cognitive Neuroscience (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Academic Press.

Baars, B.J. (2019). On Consciousness: Science and Subjectivity – Updated Works on Global Workspace Theory. Nautilus Press.

Key Scientific Papers

Baars, B.J. (1997). In the theatre of consciousness: Global workspace theory, a rigorous scientific theory of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 4(4), 292-309. Available at: https://www.wisebrain.org/media/Papers/BaarsTheaterConsciousness.pdf

Baars, B.J. (2005). Global workspace theory of consciousness: Toward a cognitive neuroscience of human experience. Progress in Brain Research, 150, 45-53. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16186014/

Baars, B.J., & Franklin, S. (2009). Consciousness is computational: The LIDA model of global workspace theory. International Journal of Machine Consciousness, 1(1), 23-32. Available at: https://philpapers.org/rec/BERCIC

Franklin, S., D’Mello, S., Baars, B.J., & Ramamurthy, U. (2009). Evolutionary pressures for perceptual stability and self as guides to machine consciousness. International Journal of Machine Consciousness, 1(1), 99-110.

Related Theoretical Work

Dehaene, S., & Naccache, L. (2001). Towards a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness: Basic evidence and a workspace framework. Cognition, 79(1-2), 1-37.

Dehaene, S., & Changeux, J.P. (2011). Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing. Neuron, 70(2), 200-227. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21521609/

Shanahan, M. (2010). Embodiment and the Inner Life: Cognition and Consciousness in the Space of Possible Minds. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Resources on Global Workspace Theory

Bernard Baars Official Website: https://bernardbaars.com/

Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness: https://theassc.org/

Wikipedia Entry on Global Workspace Theory: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_workspace_theory

LIDA Cognitive Architecture at University of Memphis: https://ccrg.cs.memphis.edu/

Trauma, Dissociation, and Consciousness

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking.

Frewen, P.A., & Lanius, R.A. (2015). Healing the Traumatized Self: Consciousness, Neuroscience, Treatment. New York: W.W. Norton.

Lanius, R.A., et al. (2015). Trauma-related dissociation and altered states of consciousness: A call for clinical, treatment, and neuroscience research. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, 27905. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4439425/

Historical Context

Baars, B.J. (1986). The Cognitive Revolution in Psychology. New York: Guilford Press.

Gardner, H. (1985). The Mind’s New Science: A History of the Cognitive Revolution. New York: Basic Books.

Clinical Applications

Siegel, D.J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Cozolino, L. (2017). The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy: Healing the Social Brain (3rd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy. New York: W.W. Norton.

0 Comments