The history of psychotherapy is filled with discoveries that emerged from unusual circumstances, and few are more striking than the origins of systematic desensitization. During World War II, a young South African physician named Joseph Wolpe was assigned to treat soldiers suffering from what was then called war neurosis, the constellation of symptoms we would now recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder. The prevailing psychoanalytic approaches seemed ineffective for these profoundly traumatized men, and Wolpe began searching for alternatives. What he discovered would revolutionize the treatment of anxiety disorders and establish behavior therapy as a legitimate clinical discipline.

Wolpe’s great insight was both simple and profound. If fear responses could be learned through conditioning, as Ivan Pavlov and John B. Watson had demonstrated, then perhaps they could be unlearned through a reverse process. Rather than spending years excavating childhood memories or interpreting dreams, perhaps therapists could directly target the anxiety response itself, weakening it through systematic exposure while the patient remained in a relaxed state. This approach, which Wolpe called reciprocal inhibition, became the foundation for exposure-based treatments that remain the gold standard for anxiety disorders more than sixty years later.

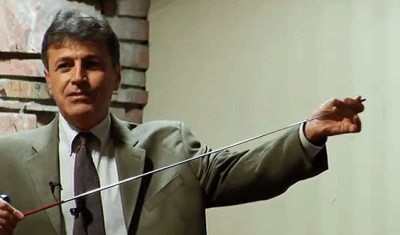

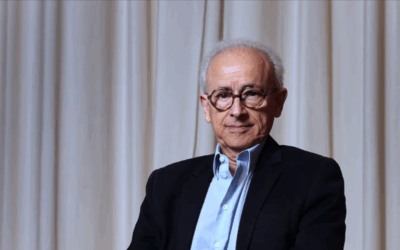

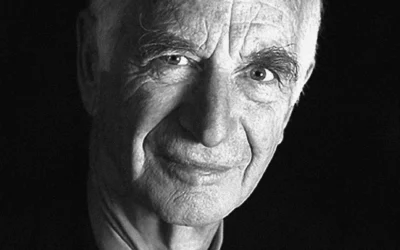

Joseph Wolpe was born on April 20, 1915, in Johannesburg, South Africa. His parents, Michael Wolpe and Sarah Millner, were Jewish immigrants who had come to South Africa from Lithuania seeking better opportunities. Joseph was the third of four children and grew up in a household that valued education and intellectual achievement. He attended Parktown Boys’ High School in Johannesburg before enrolling at the University of the Witwatersrand, where he would earn both his undergraduate degree and his medical degree.

Wolpe completed his medical training in 1939, the same year that World War II began. He initially practiced as a general physician, but the war soon redirected his career. In 1942, he joined the South African Medical Corps and was assigned to a military hospital where he treated soldiers suffering from war neurosis. These men had experienced the horrors of combat and now lived in states of chronic hyperarousal, plagued by nightmares, flashbacks, and overwhelming anxiety that prevented them from functioning normally.

The standard treatment approach at the time was psychoanalytically oriented, focusing on helping patients gain insight into unconscious conflicts that were presumed to underlie their symptoms. Wolpe tried these methods but found them largely ineffective. His patients did not improve despite months of therapy, and Wolpe grew increasingly frustrated with the gap between psychoanalytic theory and clinical reality. He began reading more widely, seeking alternative approaches that might actually help his suffering patients.

During this period, Wolpe encountered the work of the behaviorists, particularly the conditioning research of Pavlov and Watson, as well as the learning theory of Edward Thorndike and the emerging work of Clark Hull. These researchers had demonstrated that fears could be conditioned through association and that conditioned responses could be extinguished through various procedures. If human anxiety disorders were learned responses, as Watson’s Little Albert experiment suggested, perhaps they could be modified using principles derived from laboratory research on conditioning.

After the war, Wolpe pursued this line of thinking through doctoral research at the University of the Witwatersrand. He conducted experiments with cats, inducing experimental neuroses by pairing a specific environment with electric shock. The cats developed persistent anxiety responses to the experimental chamber, refusing to eat and showing physiological signs of distress whenever they were placed in that setting. Wolpe then explored methods for eliminating these conditioned fear responses.

The key discovery emerged from Wolpe’s observation that anxiety and relaxation appear to be mutually incompatible states. An organism cannot be simultaneously anxious and relaxed. If one could induce a state of relaxation while the feared stimulus was present, the relaxation response might inhibit the anxiety response, weakening the conditioned fear. Wolpe called this principle reciprocal inhibition, borrowing a term from neurophysiology to describe the process by which one response suppresses an incompatible response.

Wolpe found that he could eliminate his cats’ conditioned fears by feeding them in environments that resembled the shock chamber but were sufficiently different that the anxiety response was not overwhelming. He would begin with an environment quite different from the original, where the cat could eat comfortably. Then he would gradually move to environments more similar to the shock chamber, always ensuring that the eating response, which is incompatible with anxiety, was stronger than the fear response. Eventually, the cats could eat comfortably even in the original chamber where they had received shocks, their fears eliminated through this gradual process of reconditioning.

Wolpe received his doctorate in 1948 and immediately began applying these laboratory findings to human patients. He developed the clinical procedure that would become known as systematic desensitization, a structured approach to eliminating anxiety through graduated exposure combined with relaxation. The technique has three essential components that Wolpe refined through extensive clinical work.

First, the patient learns deep muscle relaxation, typically using a procedure adapted from Edmund Jacobson’s progressive relaxation technique. Jacobson had developed methods for systematically tensing and releasing muscle groups to achieve a state of profound physical relaxation. Wolpe taught his patients these techniques, helping them develop the capacity to enter a relaxed state on demand. This relaxation response would serve as the inhibitor of anxiety during the desensitization process.

Second, the patient and therapist collaborate to construct an anxiety hierarchy, a list of situations related to the feared stimulus arranged from least anxiety-provoking to most anxiety-provoking. For a patient with a spider phobia, the hierarchy might begin with looking at the word “spider” printed on a card, progress through looking at photographs of spiders, being in the same room as a spider in a closed container, and eventually culminate in allowing a spider to crawl on the patient’s hand. The precise content and ordering of the hierarchy is individualized for each patient based on their specific fear.

Third, the patient works through the hierarchy systematically while maintaining the relaxed state. Beginning with the least anxiety-provoking item, the patient imagines the scene while remaining relaxed. If anxiety begins to emerge, the patient signals the therapist and returns to focusing on relaxation until calm is restored. Only when the patient can imagine a scene without significant anxiety do they progress to the next item in the hierarchy. This gradual process continues until the patient can imagine even the most feared situations while remaining relaxed.

Wolpe’s early case studies demonstrated remarkable results. Patients who had suffered from phobias for years, sometimes decades, showed dramatic improvement after a relatively brief course of systematic desensitization. Wolpe tracked outcomes meticulously and reported success rates that far exceeded what psychoanalytic approaches had achieved. His 1958 book “Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition” presented these findings along with the theoretical framework underlying the approach, establishing systematic desensitization as a scientifically grounded alternative to traditional insight-oriented therapies.

The publication of this book marked a turning point in the history of psychotherapy. For the first time, a treatment approach derived from laboratory research on learning and conditioning had been systematically applied to clinical problems and shown to produce substantial improvement. Wolpe had demonstrated that behavior therapy could work, challenging the dominance of psychoanalytic approaches and opening the door to an era of empirically validated psychological treatments.

In 1960, Wolpe emigrated to the United States, initially taking a position at the University of Virginia before moving to Temple University in Philadelphia, where he would spend the majority of his American career. At Temple, he established the Behavior Therapy Unit, trained numerous students and residents in his methods, and continued refining his clinical techniques. He also became an influential advocate for behavior therapy, speaking at conferences, publishing prolifically, and engaging in debates with psychoanalytically oriented colleagues.

Wolpe developed several innovations beyond systematic desensitization. He introduced the Subjective Units of Disturbance Scale, commonly known as SUDS, a simple method for patients to rate their anxiety on a scale from zero to one hundred. This scale allows therapists and patients to track anxiety levels precisely during treatment and to identify whether progress is being made. SUDS ratings remain widely used in clinical practice and research today.

Wolpe also developed assertiveness training as a treatment for social anxiety and interpersonal difficulties. He reasoned that assertive behavior, like relaxation, is incompatible with anxiety. Patients who could learn to express their needs, set boundaries, and engage confidently in social interactions would find that their social anxiety diminished as the assertive response inhibited the fear response. Assertiveness training became a widely used component of behavior therapy for social anxiety and continues to be employed today.

Another contribution was in vivo desensitization, conducting exposure not just in imagination but in real life. While imaginal exposure was effective for many patients, Wolpe recognized that directly confronting feared situations in reality could be even more powerful. A patient afraid of heights might work through their hierarchy by actually visiting progressively higher locations rather than merely imagining them. This approach required careful planning to ensure that the patient maintained a relaxed state during real-world exposure, but it often produced faster and more durable improvement than imaginal procedures alone.

For contemporary clinical practice, Wolpe’s work provides foundational techniques that remain essential for treating anxiety disorders. The principles of graduated exposure and reciprocal inhibition underlie the exposure-based treatments recommended by the American Psychological Association and other professional organizations as first-line interventions for phobias, social anxiety, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. The specific procedures have evolved and been refined over the decades, but the core insights remain Wolpe’s.

Modern exposure therapy typically places less emphasis on relaxation than Wolpe originally prescribed. Research has shown that fear extinction can occur through exposure alone, without the explicit pairing of feared stimuli with relaxation responses. What appears most important is that the patient remains in contact with the feared stimulus long enough for the anxiety response to diminish naturally, a process called habituation. However, relaxation techniques remain valuable as tools for helping patients approach exposure exercises they might otherwise avoid and for managing the distress that exposure inevitably produces.

The concept of the anxiety hierarchy has proven extremely valuable for making exposure manageable. Patients often feel overwhelmed by the prospect of confronting their most feared situations, but they can typically tolerate beginning with less challenging exposures. As they experience success at lower levels of the hierarchy, their confidence grows and they become willing to attempt more difficult challenges. This graduated approach makes exposure accessible to patients who might refuse treatment if asked to confront their worst fears immediately.

Beyond formal therapy, Wolpe’s principles can guide personal efforts to overcome fears and anxieties. If you struggle with a specific fear, you might construct your own hierarchy of situations ranging from mildly uncomfortable to highly distressing. You could then work through this hierarchy systematically, ensuring that you stay in each situation long enough for your anxiety to decrease before moving to the next level. Practicing relaxation techniques can help you manage the discomfort that arises during self-directed exposure, making the process more tolerable and increasing the likelihood that you will persist.

Wolpe’s work also highlights the importance of not avoiding feared situations. Avoidance provides short-term relief from anxiety but prevents the extinction of fear responses. Every time you avoid something you fear, you deprive yourself of the opportunity to learn that the feared outcome does not occur or that you can cope with it if it does. This insight suggests that overcoming anxiety requires deliberately seeking out opportunities for exposure rather than organizing one’s life around avoidance.

The principle of reciprocal inhibition has applications beyond anxiety treatment. Any time you want to replace one response with another, pairing the situation that triggers the unwanted response with a competing response can be helpful. A person who tends to respond to criticism with anger might practice responding with curiosity instead, asking questions to understand the other person’s perspective. Over time, the curious response can come to inhibit the angry response, changing a problematic pattern.

Wolpe continued his clinical work and advocacy for behavior therapy throughout his career. He trained hundreds of therapists in his methods, both at Temple and through workshops and presentations around the world. He engaged in vigorous debates with critics of behavior therapy, defending the approach against charges that it was superficial, mechanistic, or dehumanizing. He argued that behavior therapy was actually more humane than traditional approaches because it produced faster relief from suffering without requiring patients to endure years of expensive, ineffective treatment.

In his later years, Wolpe expressed concern about what he saw as the dilution of behavior therapy as cognitive approaches became increasingly integrated into behavioral treatments. While he acknowledged that cognition played a role in anxiety and other disorders, he believed that the specifically behavioral techniques he had developed were the active ingredients in treatment and worried that cognitive additions might obscure this. This perspective remains a matter of debate, with contemporary research examining the relative contributions of behavioral and cognitive components in combined treatments.

Wolpe died on December 4, 1997, in Los Angeles, California, at the age of eighty-two. His legacy is most visible in the exposure-based treatments that remain central to evidence-based practice for anxiety disorders. Every time a therapist helps a patient construct an anxiety hierarchy, every time a patient practices relaxation before attempting a feared activity, every time someone overcomes a phobia through systematic exposure, the influence of Joseph Wolpe is present. He demonstrated that fears learned through conditioning could be unlearned through systematic therapeutic procedures, and this demonstration transformed both the theory and practice of psychotherapy.

Timeline of Major Events in the Life of Joseph Wolpe

1915: Born April 20 in Johannesburg, South Africa, to Michael Wolpe and Sarah Millner

1939: Completed medical degree at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg

1942-1946: Served as a medical officer in the South African Medical Corps, treating soldiers with war neurosis

1948: Received doctorate from the University of the Witwatersrand for research on experimental neuroses in cats

1948-1959: Practiced psychiatry in Johannesburg while developing and refining systematic desensitization

1956: Published “Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition” as a journal article, first presenting his theoretical framework and clinical methods

1958: Published “Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition” as a comprehensive book, establishing behavior therapy as a clinical discipline

1960: Emigrated to the United States, taking a position at the University of Virginia School of Medicine

1965: Moved to Temple University Medical School in Philadelphia, where he established the Behavior Therapy Unit

1966: Published “The Practice of Behavior Therapy,” which became a widely used clinical textbook

1979: Co-founded the Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry

1981: Received the Distinguished Scientific Award for the Applications of Psychology from the American Psychological Association

1988: Published “Life Without Fear,” presenting his methods for a general audience

1997: Died December 4 in Los Angeles, California, at the age of eighty-two

Selected Bibliography of Joseph Wolpe

Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition (1958): Wolpe’s foundational work presenting the theoretical basis of systematic desensitization and extensive case material demonstrating its effectiveness, the book that established behavior therapy as a scientifically grounded clinical approach

Behaviour Therapy Techniques: A Guide to the Treatment of Neuroses (1966): Co-authored with Arnold Lazarus, this practical manual provided detailed instructions for implementing systematic desensitization and related techniques

The Practice of Behavior Therapy (1969): A comprehensive clinical textbook presenting Wolpe’s methods for treating anxiety disorders and other conditions, updated through multiple editions over the following decades

Theme and Variations: A Behavior Therapy Casebook (1976): A collection of clinical cases illustrating the application of behavior therapy techniques to diverse problems and patient populations

Life Without Fear: Anxiety and Its Cure (1988): Written for a general audience, this book presented Wolpe’s understanding of anxiety and his methods for overcoming it in accessible terms

Legacy and Influences of Joseph Wolpe

Joseph Wolpe’s influence on psychotherapy has been profound and enduring. He demonstrated that psychological treatments could be derived from scientific research on learning and conditioning, evaluated through systematic outcome studies, and refined based on empirical evidence. This approach to treatment development, which seems obvious today, was revolutionary in an era dominated by theories and methods that had never been subjected to rigorous testing.

Systematic desensitization, Wolpe’s signature contribution, remains a core technique in exposure-based treatments for anxiety disorders. The American Psychological Association‘s Clinical Practice Guidelines identify exposure therapy as a first-line treatment for PTSD, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and specific phobias. While the specific procedures have evolved since Wolpe’s original formulations, the fundamental principles of graduated exposure and fear extinction that he established remain central to evidence-based practice.

Prolonged Exposure therapy for PTSD, developed by Edna Foa and colleagues, builds directly on Wolpe’s foundation. The treatment combines imaginal exposure to trauma memories with in vivo exposure to avoided situations, employing the same principles of graduated confrontation and fear extinction that Wolpe pioneered. Randomized controlled trials have established Prolonged Exposure as one of the most effective treatments for PTSD, and it is recommended by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and other authorities.

Exposure and Response Prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder represents another extension of Wolpe’s work. Patients are exposed to situations that trigger obsessive thoughts while refraining from the compulsive behaviors that would normally reduce anxiety. This procedure allows the anxiety response to extinguish through non-reinforced exposure, following the same logic that guided Wolpe’s original systematic desensitization work.

Wolpe’s influence extends through his many students and trainees who went on to develop their own contributions to behavior therapy. Arnold Lazarus, who collaborated with Wolpe on several publications, developed multimodal therapy and contributed to the broadening of behavior therapy to include cognitive and affective dimensions. The generation of behavior therapists trained at Temple and other institutions carried Wolpe’s methods throughout the world, establishing behavior therapy as a global movement.

The concept of the anxiety hierarchy has applications beyond formal therapy. Educators use graduated challenges to help students overcome academic anxiety. Athletic coaches employ progressive exposure to help athletes manage performance anxiety. Public speaking programs incorporate hierarchical exposure to help participants overcome fear of audiences. These applications all derive from Wolpe’s insight that fear can be overcome through systematic, graduated confrontation.

Wolpe’s development of the Subjective Units of Disturbance Scale provided a simple, practical tool that has become standard in clinical practice and research. SUDS ratings allow therapists and patients to communicate precisely about anxiety levels, to track progress over time, and to identify when interventions are or are not working. This emphasis on measurement and quantification reflects Wolpe’s commitment to making therapy an empirical enterprise.

The assertiveness training component of Wolpe’s work has influenced interpersonal skills training across many contexts. Programs for developing assertiveness in workplace settings, in educational contexts, and in personal relationships draw on the techniques Wolpe developed for helping patients express themselves more effectively. The recognition that assertive behavior can inhibit anxiety has broad applications for anyone seeking to communicate more confidently.

At Get Therapy Birmingham, exposure-based techniques derived from Wolpe’s work are central to our treatment of anxiety disorders. When we help clients construct anxiety hierarchies, practice relaxation techniques, and systematically confront feared situations, we are applying principles that Wolpe established more than sixty years ago. His demonstration that learned fears can be unlearned through structured therapeutic procedures remains one of the most important discoveries in the history of psychotherapy.

Joseph Wolpe, systematic desensitization, behavior therapy, reciprocal inhibition, exposure therapy, anxiety treatment, phobia treatment, relaxation therapy, SUDS scale, fear extinction, behavioral psychology, anxiety hierarchy, assertiveness training, PTSD treatment, evidence-based therapy

Meta Description: Discover the life and revolutionary contributions of Joseph Wolpe, the South African psychiatrist who developed systematic desensitization and established behavior therapy as a scientifically grounded treatment for anxiety disorders. Learn how his principle of reciprocal inhibition transformed the treatment of phobias, PTSD, and anxiety, creating exposure-based techniques that remain the gold standard in evidence-based psychotherapy today.

0 Comments