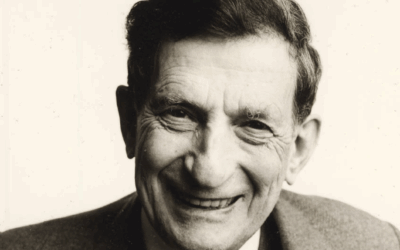

Nietzsche’s Influence and Counter Transference on Carl Jung

Nietzsche’s Influence and Counter Transference on Carl Jung

The relationship between Friedrich Nietzsche and Carl Jung was one of profound influence mixed with misunderstanding, fear, and divergence. Jung built upon Nietzsche’s pioneering explorations of the hidden depths of the human psyche, yet also harbored deep concerns about following Nietzsche’s path. A close examination reveals that Jung was both more indebted to and more conflicted about Nietzsche than he openly acknowledged.

One curious episode that highlights Jung’s ambivalent relationship to Nietzsche is his attempt to confirm one of his own theories about the collective unconscious by investigating Nietzsche’s childhood. In his seminar on Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Jung made the startling claim that the character of Zarathustra was not simply Nietzsche’s invention, but an archetypal figure stemming from the collective unconscious that had also manifested in Nietzsche’s boyhood fantasies [1].

To substantiate this claim, Jung contacted Nietzsche’s sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, inquiring if Friedrich had owned a book about pirates as a child. Jung believed that if young Nietzsche had been captivated by tales of heroic pirates, it would provide evidence for his thesis that Zarathustra represented a “primitive” archetype of the “wise old man” that had unconsciously influenced Nietzsche from an early age.

Remarkably, Nietzsche’s sister confirmed that her brother had indeed possessed a beloved book about pirates that he had requested as a Christmas gift in 1862 at the age of eighteen. For Jung, this revelation was a triumphant vindication of his theory of the collective unconscious. In the 1930s, he began citing the “pirate book” anecdote in his writings and lectures as proof that “the essential features of the Zarathustra figure” were “pre-conscious” in Nietzsche and had arisen from the “treasure-house of ancestral experience” [1].

Jung’s Fear of Nietzsche

In his autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung candidly discusses his early hesitations about reading Nietzsche, fearing that he might find himself too similar to the brilliant but troubled philosopher [1]. Jung worried that, like Nietzsche, he had “inner experiences” that could isolate him and perhaps even drive him mad if pursued too far.

This fear seems to stem from Jung’s identification with Nietzsche on both a personal and philosophical level. He drew parallels between Nietzsche’s Zarathustra and his own “No. 2” personality, a morbid layer of the unconscious, asking anxiously, “Was my No. 2 also morbid?” [1] Jung’s dread of discovering himself to be, in his words, “a blank page whirling about in the winds of the spirit, like Nietzsche,” suggests he sensed their common fascination with the irrational forces of the psyche long before he dared engage with Nietzsche directly [1].

When Jung finally did study Nietzsche in depth, he sought to portray him as a neurotic who failed to reconcile the opposites within himself – a diagnosis that, in light of Jung’s earlier comments, reads like a partially veiled self-diagnosis [2]. In his seminars on Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Jung appears intent on distancing himself from Nietzsche, exaggerating his flaws while skipping over passages that hit too close to home [2].

Particularly telling are the chapters on “The Sublime Men” and “Immaculate Perception” that Jung claimed contained “nothing very important” and rushed past [2]. These skipped passages center on Nietzsche’s concept of a mirror that reflects one’s inner depths – a metaphor for uncompromising introspection and acknowledgment of one’s shadow [2]. By glossing over these crucial sections, Jung evaded reflecting on the very aspects of Nietzsche that unnerved him with their familiarity.

Foundations and Divergences

Despite Jung’s public criticisms and private fears, Nietzsche anticipated many of Jung’s key concepts – the shadow, the collective unconscious, the centrality of opposites and their reconciliation in the journey towards wholeness [2]. Nietzsche’s writings contain seeds of ideas that Jung would develop more systematically in his own model of the psyche. The dynamic of opposing Apollonian and Dionysian forces in The Birth of Tragedy prefigures Jung’s theory of enantiodromia, or the emergence of the repressed opposite in the psyche [3].

However, Jung and Nietzsche ultimately differ in their views on the process of integrating these polarities. For Jung, a transcendent, mediating symbol is necessary to bridge opposites and facilitate the transition to a new level of consciousness [2]. This symbolic “third thing” emerges spontaneously from the tension between thesis and antithesis, and cannot be consciously invented [4].

In contrast, Nietzsche locates the catalyst for uniting opposites within the psyche itself, as an expression of the will to power. He emphasizes the individual’s role in actively cultivating and mastering the competing drives and energies within oneself [2]. Union is not achieved through an external symbol, but by harnessing the dynamic interplay of one’s multifaceted being.

Some scholars argue that Jung’s insistence on a third, supra-ordinate symbol that transcends the opposites places undue constraints on the creative process [2]. By interpreting Nietzsche’s ideas through this lens, Jung may have limited the emancipatory potential of the will to power and the role of chaos and struggle in shaping growth. Nietzsche’s Übermensch is characterized by the strength to affirm the immediate chaos of existence, not to impose a pre-structured order over it [2].

Blind Spots and Breakthroughs

It could be argued that Jung, so deeply enmeshed in his own theories, at times projected them onto his reading of Nietzsche to the point of distortion [5]. Jung claimed Nietzsche did not recognize a spiritual reality transcending bodily instincts, yet Nietzsche makes clear references to the “invisible and higher” aspects of the self that guide the ego – a position not far from Jung’s own [2].

Similarly, Jung’s charge that Nietzsche located creativity purely in the conscious will, in contrast to Jung’s view of creativity arising from the unconscious, does not hold up to scrutiny [2]. Nietzsche also speaks of unconscious forces and “the great reason of the body” as integral to the creative enterprise [5]. Such inconsistencies suggest that Jung’s desire to differentiate himself from Nietzsche may have clouded his ability to fully appreciate the nuances and implications of his predecessor’s vision.

Perhaps Jung’s most glaring misinterpretation is his conflation of Nietzsche’s will to power with Adler’s reductive notion of a drive for superiority and dominance [2]. The will to power, as Nietzsche conceives it, is not the desire to exert power over others, but to achieve self-mastery and channel one’s energies towards creation and self-overcoming [5]. By filtering the will to power through an Adlerian lens and rejecting it on that basis, Jung cut himself off from a vital resource for understanding the Nietzschean process of uniting opposites and harnessing competing psychological forces.

Despite these misapprehensions, Jung’s confrontation with Nietzsche was a watershed moment in the history of depth psychology. In grappling with this “volcanic” thinker, Jung was forced to confront the tug of war between reason and unreason in himself, and to forge his own path through that treacherous inner landscape.

The very aspects of Nietzsche that unsettled Jung – his ventures into the irrational, his radical questioning, his intimacy with the shadow – catalyzed Jung’s own descent into the unconscious. The experience of being “swept away by the same floodwaters” as Nietzsche impelled Jung to develop the conceptual and therapeutic tools to chart those waters and steer himself to firmer ground [4].

An Uneasy Kinship

In the final analysis, Jung’s relationship to Nietzsche was one of ambivalent recognition – the recognition of an essential kinship vying with the need to assert his independence. Jung could not fully embrace Nietzsche because he came too close to naming what moved Jung himself. The aspects of Nietzsche he most firmly repudiated were those that mirrored his own hidden conflicts and yearnings.

If Nietzsche’s bold expedition into the psychic underworld ended in a tragic fall, Jung saw himself as the one fated to retrieve the treasures Nietzsche had left behind and bring them to light. By acknowledging Nietzsche as a forerunner while criticizing his “morbidity,” Jung could carry forward Nietzsche’s epochal insights without having to confront the full extent of their shared impulses and uncertainties.

Yet in the end, Jung remained haunted by the suspicion that he and Nietzsche were “strange birds of a feather,” dual explorers of the soul’s uncharted continents whose voyages had been “written in the stars from the beginning” [4]. However much Jung tried to distance himself, Nietzsche’s fiery spirit continued to cast its light and shadow over Jung’s lifework, an uneasy kinship that endures as one of the most fateful in modern thought.

References

- Jung, C. G., & Jaffé, A. (1965). Memories, dreams, reflections. Vintage Books.

- Huskinson, L. (2004). Nietzsche and Jung: The whole self in the union of opposites. Brunner-Routledge.

- Nietzsche, F. (1999). The birth of tragedy and other writings (R. Speirs, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1989). Nietzsche’s Zarathustra: Notes of the seminar given in 1934-1939. Princeton University Press.

- Kaufmann, W. (2013). Nietzsche: Philosopher, psychologist, antichrist. Princeton University Press.

0 Comments