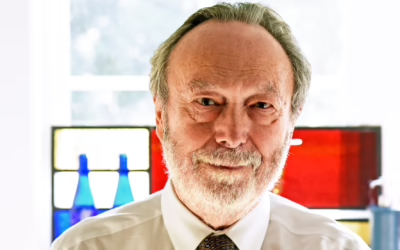

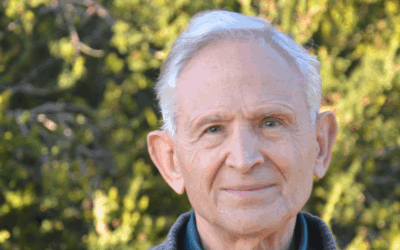

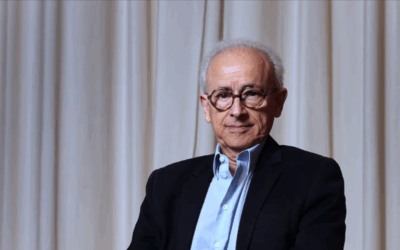

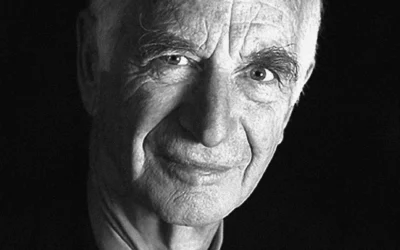

Gabor Maté: From Budapest Ghetto Baby to Voice of Compassion in Addiction’s Darkest Corners

In the urine-soaked back alleys of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, where sirens scream endlessly and the “Hastings shuffle,” a crack-driven improvisational ballet, plays out on sidewalks littered with used needles, Gabor Maté practiced a medicine most physicians would never consider. For twelve years, he walked these streets as staff physician for the Portland Hotel Society, treating people with co-occurring HIV, mental illness, and severe substance addictions. He prescribed methadone without requiring patients to attend therapy or treatment programs. He didn’t suspend prescriptions when they tested positive for illicit opioids. He visited patients in their rooms crawling with bedbugs and cockroaches. He bent down on contaminated sidewalks to urge a former nurse attempting her sixth detox to try again, knowing she might never succeed but that each attempt lasted a bit longer than the last.

“Down here, that passes for victory,” Maté observed. Treating this population, he said, resembled doing palliative work with the terminally ill.

This work, this unflinching confrontation with humanity’s most desperate attempts to escape unbearable pain, produced In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction, published in 2008. The book draws its title from the Buddhist Wheel of Life, where hungry ghosts exist in perpetual craving, unable to satisfy their desperate need. The image captures addiction’s essential paradox: the very behaviors meant to relieve suffering create more suffering, yet the compulsion persists despite catastrophic consequences.

But Maté’s understanding of addiction didn’t begin in Vancouver’s poorest neighborhood. It began January 6, 1944, in Budapest, Hungary, weeks before Nazi occupation. The infant Gabor was born into a Jewish family in the Budapest ghetto, his arrival coinciding with history’s darkest moment. When he was five months old, his maternal grandparents were killed in Auschwitz. His aunt disappeared during the war. His father endured forced labor at the hands of the Nazis and Hungarian armies.

For protection during the Holocaust, Maté’s mother entrusted her infant son to a stranger for over five weeks, a maternal separation that Maté, even nearly eighty years later, identified as formative trauma. His mother spent his first year “anxious and depressed and stressed to the extreme,” her terror and grief creating the emotional atmosphere of his earliest development. Though he consciously remembers nothing from this period, Maté recognized these experiences shaped his neurobiology, his attachment patterns, his lifelong struggles with attention deficit and compulsive behaviors.

“I am both a survivor and a child of the Nazi genocide,” he wrote, “having lived most of my first year in Budapest under Nazi occupation.” The Holocaust gave him insight into undeserved suffering, why people through no fault of their own can experience extreme pain. That recognition remained with him through medical school, through twenty years of family practice, through seven years as medical coordinator of Vancouver Hospital’s Palliative Care Unit, and ultimately to the Portland Hotel where hundreds of women patients, without exception, disclosed histories of childhood sexual abuse.

The Maté family emigrated to Canada in 1956 when Gabor was twelve, settling in Vancouver. He completed his BA from the University of British Columbia in 1969, worked briefly as high school English and literature teacher, then returned to UBC to pursue his childhood dream of becoming a physician, earning his MD in general family practice in 1977. He ran a private family practice in East Vancouver for two decades, building conventional medical career while raising three children with his wife Rae, whom he met as fellow graduate at UBC.

But something in Maté resisted conventional medicine’s approach to suffering. In 1999, he published Scattered Minds: The Origins and Healing of Attention Deficit Disorder, a controversial book that challenged prevailing understanding of ADHD as primarily genetic neurological disorder. Drawing on his own ADHD diagnosis and his observations of patients, Maté proposed that attention deficit develops as adaptive response to early childhood stress and emotional absence rather than as fixed brain difference.

The book argued that ADHD symptoms, distractibility, impulsivity, hyperactivity, hyperfocus, reflect the developing brain’s response to environment lacking attuned, calm parental presence. When caregivers are themselves stressed, traumatized, or emotionally unavailable, the infant’s developing prefrontal cortex cannot properly organize attention and self-regulation capacities. What appears as neurological disorder actually represents neurodevelopmental adaptation to inadequate early environment.

This perspective outraged many ADHD specialists. Psychologist Russell Barkley and others criticized Maté for dismissing robust genetic heritability evidence, twin studies showing 70-80 percent concordance rates, suggesting his trauma-centric view risked delaying evidence-based interventions like medication by attributing ADHD primarily to parenting failures.

In 2003, Maté published When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress, exploring connections between emotional suppression and physical illness. Drawing on his palliative care experience and extensive patient histories, he proposed that people who chronically suppress emotions, particularly anger and authentic needs, to maintain relationships and avoid conflict show higher rates of autoimmune diseases, cancer, and other serious illnesses.

The book examined how childhood experiences teaching emotional repression create adult patterns of self-abandonment. The person becomes skilled at meeting others’ needs while ignoring internal signals of distress, exhaustion, resentment. The body, unable to express emotional truth verbally or behaviorally, expresses it through illness. Maté wasn’t claiming emotions cause disease in simple causal sense but suggesting that chronic stress and emotional repression dysregulate immune function, inflammatory processes, and cellular repair mechanisms.

In 2004, Maté co-authored with developmental psychologist Gordon Neufeld Hold On to Your Kids: Why Parents Need to Matter More Than Peers, examining what they termed “peer orientation,” the phenomenon of children and adolescents forming primary emotional attachments to peers rather than parents. The book argued that modern economic pressures forcing both parents into full-time work, coupled with earlier daycare enrollment and excessive media consumption, weakens parent-child attachment bonds.

But the work that established Maté’s international reputation came from his twelve years, 1996 to 2008, at Portland Hotel Society in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The neighborhood, notorious for having North America’s highest concentration of injection drug use, HIV infection, mental illness, and poverty, provided Maté with patient population experiencing addiction’s most extreme manifestations.

His clinical approach challenged conventional addiction treatment orthodoxy. He prescribed methadone, an opioid agonist that prevents withdrawal symptoms and reduces cravings, without requiring patients to participate in counseling, twelve-step programs, or abstinence-based recovery. He didn’t view positive drug screens as treatment failure or reason to suspend medication.

Instead, Maté practiced medicine meeting people where they were. This harm reduction philosophy, treating addiction as chronic relapsing condition requiring long-term support rather than moral failing requiring willpower, brought Maté into national spotlight.

In 2008, federal Minister of Health Tony Clement attacked physicians working at Insite, Vancouver’s legal supervised injection facility, calling them unethical. Maté publicly defended them, arguing that supervised injection saves lives by preventing overdose deaths, reducing HIV and hepatitis C transmission, and connecting highly marginalized people to medical care and social services.

Through thousands of clinical encounters, Maté developed core insight that became his central theoretical contribution: addiction represents attempt to solve a problem, not the problem itself. The question isn’t “why the addiction?” but “why the pain?” All addictions, from his patients’ heroin and crack cocaine to his own compulsive purchasing of classical music CDs, serve similar function. They provide temporary relief from unbearable internal states that developed as adaptive responses to early trauma.

Maté defined addiction broadly: any behavior or substance used to relieve pain in the short term that leads to negative consequences in the long term. The answer, Maté proposed, lies in early childhood environment where brain’s reward pathways develop. Contrary to disease model locating addiction in genes, Maté argued the source resides in developmental experiences, particularly trauma, neglect, abuse, emotional absence that wire emotional patterns into unconscious.

An infant separated from attuned caregiver develops nervous system primed for dysregulation. A child experiencing abuse learns to dissociate from body and emotions to survive. These aren’t moral failures but neurodevelopmental adaptations.

This framework challenged both medical model viewing addiction as brain disease and moral model viewing it as character weakness. Maté proposed addiction as injury, wound to psychological and neurological development created by adverse childhood experiences. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study, research from Kaiser Permanente and CDC examining how childhood trauma correlates with adult health outcomes, supported Maté’s emphasis on developmental factors.

The ACE research demonstrated that experiences including abuse, neglect, household dysfunction, parental mental illness, substance abuse, incarceration, create dose-dependent risk for virtually every major health problem. People with ACE scores of four or more show dramatically elevated rates not just of addiction but of depression, suicide attempts, heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, liver disease.

Maté developed Compassionate Inquiry, a psychotherapeutic method revealing what lies beneath the appearance people present to world. The approach involves asking questions that penetrate defensive structures to access hidden assumptions, implicit memories, and body states forming the real message words both conceal and reveal.

The therapist might ask, “What are you getting from this that you can’t get any other way?” Or “When you use, what happens to the pain you were feeling?” The questions aren’t accusatory but curious, inviting exploration rather than demanding change. The therapeutic stance embodies qualities Maté believes facilitate healing: presence, acceptance, curiosity, compassion for all parts of the person including those engaged in self-destructive behaviors.

This connects naturally to Internal Family Systems. Both approaches recognize that aspects of self working at cross purposes represent protective strategies developed at different times under different circumstances.

The integration with trauma treatment modalities proved particularly important. The body keeps the score, that trauma encodes in somatic and subcortical systems inaccessible to verbal therapy.

Polyvagal theory provides framework for understanding how trauma disrupts autonomic regulation, leaving people oscillating between sympathetic hyperarousal and dorsal vagal shutdown. Maté’s patients, many lacking safe early attachments that calibrate polyvagal system, used drugs to manually regulate states their nervous systems couldn’t manage naturally.

Somatic Experiencing, focusing on completing defensive responses and discharging held activation through body-based processing, offered tools for addressing subcortical trauma underlying addiction. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, working with procedural memory and autonomic patterns, similarly addressed trauma at neurobiological level where drugs had been recruited for regulation.

EMDR and brainspotting provided methods for processing traumatic memories without requiring extended verbal narration that could overwhelm fragile patients.

Research on right brain development and affect regulation illuminated why early relational trauma creates lifelong vulnerability. Without “good enough” early attachment, right brain circuits underlying emotional regulation, stress tolerance, and interpersonal connection develop incompletely. Addiction becomes attempt to regulate what should have been regulated relationally.

Structural dissociation helped explain how severely traumatized individuals fragment into apparently normal parts trying to function and emotional parts holding traumatic memories.

In 2010, Maté became interested in ayahuasca, traditional Amazonian plant medicine, and its potential for treating addictions. He partnered with Peruvian Shipibo ayahuasquero and began leading multi-day retreats. A First Nations community on Vancouver Island invited him to conduct retreat for members struggling with addiction and intergenerational trauma. University of Victoria and University of British Columbia researchers conducted observational study.

Maté’s advocacy for psychedelics, including MDMA, psilocybin, and ayahuasca, generated both enthusiasm and concern. He proposed these substances, used in proper therapeutic context with intention and integration, facilitate access to emotional material normally defended against. This aligns with emerging research showing psychedelic-assisted therapy demonstrating remarkable efficacy for PTSD, depression, and addiction.

In 2022, Maté published with his son Daniel The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture, his most comprehensive synthesis. The book became New York Times and international bestseller, expanding Maté’s thesis that Western culture’s individualism, materialism, disconnection from nature and community creates toxic environment breeding trauma, addiction, mental illness, and chronic disease.

The “myth of normal” refers to accepting current cultural conditions as natural or inevitable when they actually represent profound departure from environments supporting human flourishing. The problem isn’t individual pathology but cultural pathology, systemic disconnection and dehumanization that traumatizes entire populations.

Maté argues that capitalism’s demands for constant growth, consumption, and productivity force parents away from children, fragment communities, commodify relationships, and create pervasive sense of inadequacy. The resulting epidemic of loneliness, stress, and emotional dysregulation drives people toward addictions and manifests in physical illness through chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation.

This political dimension distinguishes Maté from many trauma therapists. While others focus primarily on clinical interventions, Maté explicitly links individual suffering to social conditions including poverty, racism, colonization, economic inequality, and what he terms society’s “war on drugs” actually functioning as war on traumatized people.

Maté’s media presence expanded dramatically through podcast appearances including Joe Rogan Experience, Tim Ferriss Show, Russell Brand’s Under The Skin, and extended conversations with Glennon Doyle on We Can Do Hard Things. His lectures attract audiences of thousands. His books have sold millions of copies, been translated into over forty languages, and influenced addiction treatment policies worldwide.

In March 2023, Maté conducted live-streamed interview with Prince Harry, diagnosing the Prince publicly with PTSD, ADHD, anxiety, and depression based on conversation and reading his autobiography.

The documentary Physician, Heal Thyself, directed by Asher Penn and premiered at Vancouver International Film Festival in 2023, examined Maté’s life and work with unusual intimacy. Maté’s willingness to position himself as subject of his own medicine, to acknowledge his imperfections and ongoing challenges, modeled vulnerability and authenticity he advocates therapeutically.

Maté received numerous honors including the Hubert Evans Prize for Literary Non-Fiction for In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, City of Vancouver’s Civic Merit Award for his contributions to understanding mental health and addiction, and in 2018, the Order of Canada, the country’s highest civilian distinction. In 2024, he received Simon Fraser University’s Nora and Ted Sterling Prize in Support of Controversy for his research linking trauma to health outcomes, and Hungarian President presented him with the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of Hungary.

Addiction theorist Stanton Peele criticized Maté for offering “reductionist vision of addiction” elevating childhood trauma to all-encompassing cause while sidelining social, cultural, and voluntary elements. The debate reflects broader tensions in mental health between biological and environmental explanations.

For depth psychology, Maté provides bridge between Jungian concepts and contemporary neuroscience. His emphasis on unconscious emotional patterns driving behavior, on symptoms serving protective functions, on healing requiring integration of split-off material, all resonate with depth psychology’s core insights.

The concept of “hungry ghosts” itself carries archetypal resonance. These beings represent universal human experience of craving that cannot be satisfied. Whether manifesting as addiction to substances, achievement, consumption, attention, or control, the hungry ghost pattern reflects what Jung might call shadow, the rejected aspects of psyche seeking satisfaction through compulsive behaviors.

Now officially retired from clinical practice, Maté at eighty continues traveling and speaking extensively on trauma, addiction, childhood development, and cultural healing. He leads workshops, retreats, and trainings in Compassionate Inquiry. He advocates for policy changes supporting harm reduction, Indigenous healing practices, decriminalization, and psychedelic research.

From infant in Budapest ghetto to physician in Vancouver’s most desperate neighborhood to global voice for compassionate approach to suffering, Maté’s journey illustrates how early trauma, when processed rather than perpetuated, can generate wisdom and empathy serving collective healing. His insistence that addicts are not moral failures but wounded human beings deserving care and dignity challenges punitive attitudes still dominating drug policy and social responses to addiction.

Timeline

1944: Born January 6 in Budapest, Hungary, to Jewish family during Nazi occupation

1944: Five months old, maternal grandparents killed in Auschwitz

1956: Emigrated to Canada, settled in Vancouver

1969: Earned BA from University of British Columbia

1977: Earned MD from University of British Columbia

1977-1997: Twenty years in private family practice

1990s: Seven years as medical coordinator, Palliative Care Unit, Vancouver Hospital

1996-2008: Twelve years staff physician, Portland Hotel Society, Downtown Eastside

1999: Published Scattered Minds

2003: Published When the Body Says No

2004: Co-authored Hold On to Your Kids

2008: Defended Insite physicians

2008: Published In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts

2010: Began ayahuasca work

2011: Received Civic Merit Award

2018: Appointed Member of Order of Canada

2022: Published The Myth of Normal

2023: Interview with Prince Harry

2023: Documentary Physician, Heal Thyself

2024: Received SFU Sterling Prize, Officer’s Cross Order of Merit of Hungary

Bibliography

Maté, G. (1999). Scattered Minds. Toronto: Knopf Canada.

Maté, G. (2003). When the Body Says No. Toronto: Knopf Canada.

Neufeld, G. & Maté, G. (2004). Hold On to Your Kids. Toronto: Knopf Canada.

Maté, G. (2008). In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts. Toronto: Knopf Canada.

Maté, G. & Maté, D. (2022). The Myth of Normal. New York: Avery.

0 Comments