Janina Fisher: Revolutionizing Trauma Treatment Through Structural Dissociation and Parts Work

On a September day in 1989, a young predoctoral intern sat in a grand rounds presentation at what would later become the Trauma Center, listening to Judith Herman challenge everything psychotherapy held sacred. This was still the age of Freud, when most clinicians remained committed to the talking cure and its emphasis on fantasy, defense, and intrapsychic conflict. Herman said something that would change the trajectory of trauma treatment: “Doesn’t it make more sense that people have developed symptoms because of real things that happened to them, not because of their infantile fantasies?”

For Janina Fisher, that single statement crystallized what clinical experience had been showing but therapeutic theory could not accommodate. She thought, “Oh my God, of course, this makes so much more sense.” In that moment, she committed her career to the study and treatment of trauma. What she could not know then was that she would become one of the field’s most influential pioneers, developing treatment approaches that would transform how thousands of therapists worldwide understand and work with complex trauma and dissociation.

Fisher’s journey reflects the broader evolution of trauma treatment over the past forty years. She entered the field when child abuse was minimized, when therapists still believed their patients’ symptoms represented intrapsychic conflicts rather than realistic responses to overwhelming experience. Classical psychodynamic therapy, the dominant approach, proved inadequate for traumatized clients who were “so overwhelmed by feelings and memories” that verbal processing only intensified their suffering. Yet the profession kept using these methods because, as Fisher notes, “that’s what we were supposed to do.”

What would eventually distinguish Fisher’s work was her willingness to abandon what wasn’t working and search for what would. This search led her to integrate neuroscience research with body-centered approaches, dissociation theory with parts work, creating treatment models that address trauma’s fragmenting effects directly rather than trying to force coherent narrative from incoherent experience. Her foundational book, Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors: Overcoming Internal Self-Alienation (2017), synthesizes three decades of clinical innovation into accessible framework now taught worldwide.

Biographical information about Fisher’s early life and education reveals a personal connection to trauma work she discovered only years into her career. She completed her doctoral training in clinical psychology, though specific details about her graduate institution remain less documented than her professional affiliations. What is known is that she began treating individuals, couples, and families in 1980, gaining extensive experience before the formal recognition of posttraumatic stress disorder significantly shaped clinical understanding.

The pivotal moment came during her predoctoral internship in 1989 when Herman’s presentation catalyzed her commitment to trauma specialization. At that time, Herman had just published Trauma and Recovery, introducing the concept of complex PTSD and arguing that prolonged, repeated trauma produces symptom patterns distinct from single-incident PTSD. Fisher recognized immediately that this framework made sense of clinical presentations that didn’t fit existing diagnostic categories.

A decade into her trauma work, Fisher discovered why this field resonated so deeply. Her eighty-five-year-old father disclosed for the first time that both of Fisher’s parents had been trauma survivors. “No wonder I felt this passion to do work with trauma,” she reflected. “I didn’t know why, but of course, in that moment, I knew why.” This revelation echoes common patterns where clinicians drawn to trauma work often carry intergenerational trauma that remains unspoken until middle age or later.

Fisher joined the faculty at The Trauma Center, an outpatient clinic and research center founded by Bessel van der Kolk, where she became instructor and supervisor. This position placed her at the epicenter of emerging trauma treatment innovation. Van der Kolk, himself a pioneer challenging conventional approaches, was developing what would become foundational understanding that the body keeps the score, that trauma lodges in somatic and subcortical systems inaccessible to verbal therapy.

The collaboration proved transformative. One day during a seminar Fisher was teaching at the Trauma Center, van der Kolk entered unexpectedly, listened to her presentation, then stood up and started clapping. “This is something you have to do,” he told her, insisting she take her work public. The endorsement was extraordinary because van der Kolk did not typically attend staff seminars. “He’s known for being difficult,” Fisher notes, “but what most people don’t know is that he has such a generous heart. The mission for him is so important. He sent people out into the world to carry his mission. So here I am.”

Fisher also served as instructor at Harvard Medical School, bringing trauma specialization into academic medicine at a time when psychiatric training still marginalized trauma as peripheral concern. Her position at Harvard provided platform for integrating neuroscience research with clinical practice, translating laboratory findings about fear conditioning, memory consolidation, and stress physiology into therapeutic interventions.

Additionally, Fisher became Assistant Educational Director at the Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute, collaborating closely with Pat Ogden. This partnership produced Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment (2015), co-authored with Ogden, which integrated body-centered trauma treatment with parts work and structural dissociation theory. The collaboration enriched both approaches, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy gaining sophistication in working with fragmented self-states while Fisher’s dissociation framework gained concrete somatic interventions.

Fisher served as past president of the New England Society for the Treatment of Trauma and Dissociation, positioning her as leader in the dissociation specialist community. She became an EMDR International Association Credit Provider, integrating Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing developed by Francine Shapiro into her treatment approach. Her work bridges multiple therapeutic modalities rather than promoting single method, reflecting recognition that complex trauma requires flexible, integrative approaches.

The theoretical foundation of Fisher’s work rests on structural dissociation theory, developed by Onno van der Hart, Ellert Nijenhuis, and Kathy Steele in their comprehensive text The Haunted Self: Structural Dissociation and the Treatment of Chronic Traumatization (2006). This theory proposes that trauma fundamentally fragments consciousness and personality, producing distinct self-states or “parts” that operate with relative autonomy. These parts are not metaphorical but represent actual divisions in information processing, each with characteristic patterns of emotion, cognition, sensation, and behavior.

The theory distinguishes three levels of structural dissociation. Primary structural dissociation involves division between what the authors call the Apparently Normal Part (ANP) and the Emotional Part (EP). The ANP attempts to function in daily life, going through motions of work, relationships, and survival. The EP holds traumatic memories, defensive responses, and overwhelming affects that the ANP cannot integrate. This split characterizes simple PTSD, where someone can function normally until traumatic memories intrude as flashbacks, nightmares, or triggered states.

Secondary structural dissociation, characteristic of complex PTSD, involves one ANP and multiple EPs. Different emotional parts hold different traumatic experiences or defensive responses. One EP might carry terror and the freeze response, another rage and the fight response, another desperate attachment-seeking, another complete shutdown. The person shifts between these states depending on triggers, often without conscious awareness or sense of continuity between them.

Tertiary structural dissociation, seen in Dissociative Identity Disorder, involves multiple ANPs as well as multiple EPs. Different apparently normal parts attempt to manage different life domains, work versus relationships versus parenting, each with characteristic presentation. The fragmentation becomes so extensive that distinct identities with separate memories, preferences, and senses of self emerge.

Fisher’s clinical innovation involved recognizing that all these levels of dissociation represent spectrum rather than distinct categories. Many clients with complex trauma exhibit secondary structural dissociation without meeting full criteria for DID, yet standard PTSD treatment fails because it assumes coherent self that can process traumatic memory. These clients shift between parts unpredictably, one moment appearing functional and insightful, next moment overwhelmed and childlike, then defensive and hostile, then completely numb. Traditional therapy often escalates these shifts because exploration of traumatic material activates emotional parts that the client cannot regulate.

Fisher developed what she calls Trauma-Informed Stabilization Treatment (TIST) specifically for this population. The approach prioritizes safety and stabilization over memory processing, recognizing that fragmented clients need internal coherence before they can engage trauma directly. TIST teaches clients to recognize their parts, understand that different self-states serve protective functions, and develop Adult Self or Going-On-With-Normal-Life part that can mediate between conflicting parts.

The concept of the Adult Self represents Fisher’s crucial contribution. In structural dissociation theory, the ANP is defensive part attempting to deny trauma and maintain functioning, not authentic integrated self. Fisher recognized that treatment required helping clients access or develop what she calls the Adult Self, the capacity to observe experience with both compassion and perspective. This Adult Self can witness emotional parts without becoming them, can hold dual awareness of past trauma and present safety, can facilitate communication between parts that otherwise operate in isolation.

Developing Adult Self involves learning to notice when parts have taken over versus when observing consciousness remains present. Someone caught in a child part might feel small, powerless, terrified, without access to adult knowledge that current situation is safe. The Adult Self can recognize, “A young part of me feels terrified right now, but I am actually safe. This is a memory, not current danger.” This recognition doesn’t eliminate the terror but creates psychological distance from it, preventing complete identification with the part’s experience.

Fisher emphasizes that parts are not the problem but the solution trauma survivors developed to survive the unsurvivable. When a child cannot escape abuse and fighting back makes things worse, developing a part that dissociates and goes away protects awareness from being shattered. When overwhelming emotions threaten to destroy fragile functioning, a part that holds those emotions while another part goes through daily life motions allows survival. The parts deserve appreciation, not rejection.

This reframe from pathology to adaptation represents paradigm shift. Rather than trying to eliminate symptoms, TIST helps clients understand symptoms as information about which parts have been activated and what those parts need. Self-harm might indicate a part feeling such shame and self-hatred that the only relief comes through punishment. Addiction might represent a part desperately seeking soothing that was never provided in childhood. Suicidality might reflect a part that learned the only way to stop pain was to stop existing.

Understanding symptoms as parts communication changes therapeutic relationship fundamentally. The therapist’s task shifts from fixing problems to facilitating dialogue among parts, helping them recognize they are all trying to protect the same person. The part that self-harms and the part that wants to stop self-harming are both trying to manage pain, just with conflicting strategies. When these parts can communicate rather than battle, new solutions emerge.

Fisher’s work integrates extensively with Internal Family Systems (IFS), developed by Richard Schwartz. Both approaches recognize parts as normal aspect of psyche that becomes problematic only when parts cannot communicate and coordinate. Both emphasize accessing Self or Adult Self that can lead the internal system. Both frame symptoms as protective strategies rather than pathology.

The difference is that IFS was developed primarily with higher-functioning clients and assumes all people have access to Self energy characterized by curiosity, compassion, clarity, and calm. Fisher’s work with severely traumatized populations found that many clients cannot access Self without extensive preparation. Their trauma occurred so early and repeatedly that they never developed secure internal ground from which to observe experience. For these clients, Adult Self must be co-created in therapeutic relationship rather than simply accessed.

Additionally, Fisher’s grounding in structural dissociation theory provides more detailed framework for understanding different types of parts. IFS distinguishes managers (parts that control and organize), firefighters (parts that react to emotional pain with impulsive behaviors), and exiles (parts carrying vulnerable emotions). Structural dissociation distinguishes ANPs (parts attempting normal life functioning) and EPs (parts holding traumatic memory and defensive responses), with recognition that multiple variations of each exist.

Integration of these frameworks enriches both. IFS practitioners working with complex trauma benefit from Fisher’s attention to how dissociative processes operate and what stabilization looks like before attempting unburdening or retrieval of exiles. Trauma therapists trained in structural dissociation benefit from IFS emphasis on accessing Self and the specific techniques IFS provides for working with protective parts and burdened exiles.

Fisher’s approach to working with parts emphasizes several key principles. First, all parts deserve respect and appreciation. They developed to serve protective functions even if their strategies no longer serve. Second, parts need acknowledgment before they can change. Trying to eliminate parts or override their protective functions triggers escalation as the parts fight harder to maintain control. Third, parts hold wisdom about what happened and what the person needed but didn’t receive. Attending to parts’ communications provides crucial information.

Fourth, healing happens through developing internal relationships among parts rather than through fusion or elimination. The goal is not integration in the sense of parts disappearing but integration as communication, coordination, and cooperation among parts. Fifth, this internal relationship-building requires the presence of Adult Self capable of holding compassion for all parts simultaneously, even when parts appear contradictory.

Practically, Fisher teaches clients to notice when parts activate through tracking somatic signals. Different parts have characteristic body signatures. A child part might manifest as constriction in chest, shallow breathing, feeling small. A fight part might show up as tension in jaw and shoulders, clenched fists, heat. A shutdown part produces numbness, heaviness, disconnection. Learning to recognize these somatic signatures provides early warning that parts have activated before they completely take over awareness.

Once clients notice part activation, they practice what Fisher calls “parts mapping,” identifying which parts exist in their internal system and what function each serves. A client might recognize a hypervigilant part always scanning for danger, a perfectionist part trying to prevent criticism, a caretaker part focused on others’ needs, a child part holding fear and longing, an angry part holding justified rage, a suicidal part believing death is the only escape. Mapping these parts externalizes what previously felt like chaotic internal experience.

Fisher emphasizes using language that acknowledges parts without strengthening dissociative barriers. Rather than “my child part” which can reinforce separation, she encourages “a young part of me” or “the part of me that holds childhood fear.” This language maintains awareness that all parts belong to one person while still recognizing their distinct presentations. Similarly, rather than saying “I am angry,” which identifies the whole self with one part’s emotion, “a part of me feels angry” creates space for Adult Self observation.

The therapeutic relationship becomes vehicle for developing Adult Self. Fisher’s presence as calm, attuned, compassionate witness provides model for how clients can relate to their own parts. When a client shifts into a young terrified part, Fisher doesn’t try to pull them back to adult functioning but instead speaks directly to that part with appropriate tone and language. “I can see how frightened you are. You’re remembering something really scary. But you’re here with me now, and we’re safe.”

This dual-level communication, addressing both the part and the Adult Self simultaneously, helps strengthen the observing function. Fisher might say, “A young part of you feels terrified right now, but I want you to notice that you, sitting here with me, are actually safe.” This intervention grounds the client in present reality while validating the part’s experience, preventing retraumatization while allowing emotional processing.

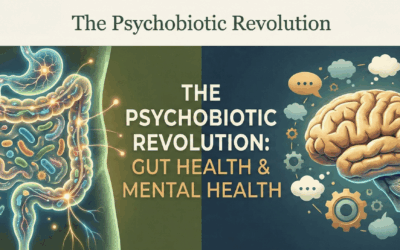

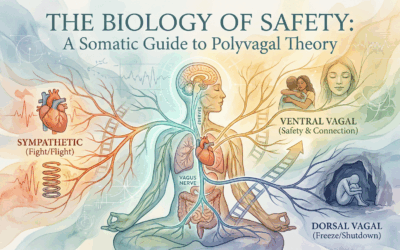

Fisher’s work integrates neuroscience research extensively, particularly findings from Allan Schore on right brain affect regulation, Stephen Porges on polyvagal theory, and Bessel van der Kolk on how trauma affects the body. She recognizes that parts represent state-dependent organization of neural networks. Different parts involve different patterns of autonomic activation, different regions of brain activity, different neurochemical profiles.

When someone shifts from Adult Self to child part, this is not merely psychological but neurobiological event. The shift involves changes in autonomic state, typically from ventral vagal social engagement to sympathetic fight-flight or dorsal vagal shutdown. Different implicit memories become accessible, different emotional responses activate, different cognitive capacities come online or offline. Understanding this helps both therapist and client recognize part activation as nervous system event requiring somatic intervention, not just cognitive reframe.

Fisher incorporates Sensorimotor Psychotherapy techniques developed by Pat Ogden to work with parts somatically. When a child part activates with collapsed posture and constricted breathing, somatic interventions like gently lengthening the spine or deepening the breath can help shift the nervous system toward more regulated state. This creates physiological conditions that support Adult Self emergence. The body standing upright sends different signals to the brain than the body curled in defensive collapse.

Similarly, EMDR can be adapted for parts work by having Adult Self witness while specific parts receive bilateral stimulation processing. Rather than processing trauma from undifferentiated first-person perspective which risks overwhelming the client, the Adult Self maintains dual awareness: “I’m watching the young part of me who experienced that trauma process those memories while I remain grounded in present safety.” This prevents retraumatization while allowing emotional processing.

Brainspotting, developed by David Grand, similarly can be used with parts. The client identifies where in visual field a particular part’s activation feels strongest, then maintains gaze there while processing occurs. This allows accessing and resolving trauma held by specific parts without activating all parts simultaneously, which would overwhelm the system.

Fisher’s treatment model addresses specific clinical challenges that complicate trauma therapy. Self-harm, addiction, suicidality, and eating disorders all respond poorly to standard interventions because they serve crucial regulatory functions for parts of the client even as they threaten the whole person’s wellbeing. TIST recognizes these behaviors as communications from parts, not willful choices to be suppressed.

For self-harm, Fisher helps clients identify which part engages in self-injury and what function it serves. Often a part believes physical pain is the only way to release overwhelming emotional pain, or that punishment is deserved and necessary. Rather than trying to stop the behavior directly, Fisher facilitates dialogue between the self-harming part and other parts who are frightened by self-harm. When the self-harming part feels heard and its protective function acknowledged, it often becomes willing to try alternative strategies.

Addiction similarly reflects parts attempting to manage unbearable internal states. One part craves substances to numb pain, another part wants sobriety to maintain functioning, yet another part holds shame about addiction. These parts battle each other, producing cycles of use and abstinence that feel beyond voluntary control. TIST helps clients recognize all parts want the same thing, relief from suffering, but disagree about methods. When parts can communicate rather than fight, the addicted part’s legitimate need for soothing can be addressed through healthier means.

Suicidality, perhaps the most frightening symptom, often represents a part that knows no other way to escape unbearable pain. This part may have developed in childhood when death truly seemed the only escape from abuse. Fisher helps clients recognize the suicidal part without becoming it, to hear its desperate communication without acting on its solution. Often just recognizing and validating this part’s pain reduces suicidal urges because the part feels finally heard.

Fisher developed the Living Legacy Flip Chart (2022) as psychoeducational tool for helping clients understand trauma’s effects on body and mind. The flip chart normalizes trauma responses, explains how different parts develop, and provides visual framework for recognizing current triggers as echoes of past danger. This educational component proves crucial because clients typically interpret their symptoms as evidence of defectiveness rather than as understandable responses to overwhelming experience.

Her workbook Transforming the Living Legacy of Trauma: A Workbook for Survivors and Therapists (2021) provides structured exercises for both clients and therapists working with trauma’s ongoing effects. The workbook bridges psychoeducation with practical intervention, helping clients develop skills for recognizing parts, managing overwhelming states, and building internal cooperation among defensive systems that previously operated in conflict.

Fisher’s seminal book Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors: Overcoming Internal Self-Alienation (2017) synthesizes her decades of clinical work into comprehensive framework. The book addresses therapeutic approaches to traumatic attachment, working with undiagnosed dissociative symptoms, integrating right brain to right brain treatment methods, and creating internal sense of safety and compassionate connection to dis-owned selves.

The book’s reception established Fisher as leading authority on structural dissociation treatment. Pat Ogden praised it as “outstanding contribution to the field” demonstrating “exceptional ability to synthesize the best of cutting-edge trauma psychotherapies into brilliant and unique roadmap.” Giovanni Liotti noted the book dealt with “fragmentation of self-experience and strategies for identifying non-integrated parts during clinical exchanges in convincing and original way rarely seen.”

Fisher lectures internationally on integrating neuroscience research with trauma treatment paradigms. She has been invited speaker at Cape Cod Institute, Harvard Medical School Conference Series, EMDR International Association Annual Conference, University of Wisconsin, University of Westminster in London, Psychotraumatology Institute of Europe, and Esalen Institute. Her teaching emphasizes practical application, showing therapists concrete interventions rather than abstract theory.

She received the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD) Lifetime Achievement Award in 2020, recognizing her pioneering contributions to understanding and treating dissociative disorders. The award acknowledged both her clinical innovation and her role in training thousands of therapists worldwide. She is Advisory Board member of the Trauma Research Foundation and Patron of the John Bowlby Centre, connecting her work to attachment theory foundations.

For depth psychology practitioners, Fisher’s work provides neurobiologically grounded framework for engaging what Jung described as complexes and what psychoanalysis calls internal objects. Jung recognized that psyche organizes into relatively autonomous functional units, complexes that can take control of consciousness and operate with their own agendas. When a complex is constellated, the person experiences characteristic emotional states, somatic sensations, and behavioral impulses that feel foreign to ego consciousness.

Fisher’s parts work operationalizes complex theory, giving therapists and clients concrete language and methods for identifying and working with these autonomous psychic structures. Rather than treating complexes as mysterious forces that occasionally seize control, TIST recognizes them as parts with legitimate protective functions that deserve relationship rather than repression. The work resembles Jung’s active imagination, creating dialogue between ego and unconscious, but with added structure and trauma sensitivity.

Shadow work, the process of recognizing and integrating disowned aspects of self, becomes more accessible through parts framework. The shadow consists precisely of those parts that were too threatening, shameful, or overwhelming to integrate into conscious identity. A child who needed to appear perfect to avoid punishment develops parts holding rage, vulnerability, playfulness, all the human responses that threatened parental approval. These shadow parts don’t disappear but continue operating unconsciously, emerging through symptoms and projections.

Fisher’s approach to shadow integration emphasizes that these parts cannot be simply brought into consciousness through interpretation or insight. They are defended against because they carry intolerable affects the nervous system cannot regulate. Integration requires first developing Adult Self capacity to hold these affects without being overwhelmed, then gradually building relationship with shadow parts, learning what they protect and what they need.

The therapeutic relationship provides what Allan Schore calls interactive regulation, the therapist’s regulated nervous system helping co-regulate the client’s dysregulated states. Fisher embodies this principle, maintaining calm compassionate presence when clients shift into parts that carry terror, rage, shame, or collapse. Her regulation provides external support until clients develop internal Adult Self capacity for self-regulation.

Fisher’s influence on contemporary trauma treatment operates through multiple channels. Her books have become required reading in many graduate trauma programs. Her training workshops fill internationally, with therapists seeking practical guidance for working with clients who don’t respond to standard approaches. Her integration of structural dissociation theory with body-based methods, parts work with neuroscience, has created accessible framework where previously existed primarily academic theory or technique-focused training.

Particularly valuable is her attention to therapist self-care and countertransference. Working with severely traumatized, fragmented clients activates therapist’s own parts. When a client becomes enraged, the therapist might shift into their own frightened child part. When a client becomes helpless, the therapist might activate a rescuer part that overextends boundaries. Fisher teaches therapists to notice their own part activation and return to Adult Self. “The little kid may be inside you,” she tells herself, “but the therapy doesn’t need the little kid. The therapy needs a therapist.”

This recognition that therapists have parts too normalizes countertransference without pathologizing it. Rather than seeing strong emotional reactions to clients as therapeutic failures, Fisher helps therapists recognize these as information about what’s happening in the relational field. If the therapist feels suddenly exhausted, perhaps they’re carrying the client’s dorsal vagal shutdown. If the therapist feels unexpected anger, perhaps they’re resonating with the client’s disowned rage part. Tracking these reactions provides valuable clinical data.

Fisher also addresses shame, recognizing it as perhaps the most toxic legacy of trauma. Shame involves not just negative self-evaluation but somatic collapse, the desire to disappear, the conviction that self is fundamentally defective and unworthy of connection. Trauma survivors develop parts that carry unbearable shame about what happened to them, shame they couldn’t prevent or escape, shame about their responses and symptoms.

TIST works with shame by recognizing it as survival strategy rather than accurate self-assessment. When a child experiences abuse, they cannot comprehend that their caregiver is dangerous because this threatens attachment on which survival depends. Instead, the child internalizes that something must be wrong with them to warrant such treatment. Shame becomes protective adaptation that preserves attachment by locating the problem in the child’s defectiveness rather than the parent’s violation.

Healing shame requires helping clients recognize these shame-carrying parts as younger selves who developed brilliant if painful strategies to make sense of the incomprehensible. The Adult Self can hold compassion for the parts that internalized shame, recognizing they were doing the best they could with the developmental capacities available. This compassionate witnessing gradually allows shame to transform from global self-condemnation to specific memory of what happened without the conclusion that it defines self-worth.

Critics note that while parts language provides useful clinical tool, questions remain about ontological status of parts. Are they actual distinct self-states with separate neural substrates or metaphorical constructions useful for organizing experience? Neuroscience research on state-dependent memory, dissociative disorders, and switching between self-states suggests neurobiological correlates exist, but whether these constitute separate entities or different activation patterns of unified system remains debated.

Additionally, concern exists that parts work might reinforce dissociative defenses rather than resolving them. If therapy strengthens identification with separate parts, might this increase fragmentation? Fisher addresses this by emphasizing that goal is not making parts more real but helping them communicate and cooperate under Adult Self guidance. The strengthening occurs in connecting function, not separating function.

Some question whether Adult Self concept differs substantially from IFS Self or simply represents rebranding. Fisher’s contribution appears to be recognizing that severely traumatized clients may not have developed Self capacity and require specific therapeutic support to build it, whereas IFS assumes Self exists in everyone and simply needs accessing. This distinction proves clinically crucial for working with most impaired populations.

Despite these concerns, Fisher’s approach has demonstrated remarkable clinical utility with populations other methods struggle to help. Clients with treatment-resistant depression, chronic suicidality, severe dissociation, and complex trauma often respond to parts work when they haven’t responded to cognitive behavioral therapy, medication, or standard trauma processing. The framework provides hope and practical direction for both clients and therapists working with seemingly intractable suffering.

What Fisher has accomplished fundamentally is translating theoretical understanding of structural dissociation into accessible clinical approach that any therapist can learn. Where van der Hart, Nijenhuis, and Steele provided comprehensive theory in The Haunted Self, Fisher provided practical roadmap for actually treating the dissociation that theory described. Where neuroscience demonstrated trauma’s fragmenting effects on consciousness, Fisher showed how to work therapeutically with those fragments.

Her integration of multiple approaches, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, EMDR, IFS, structural dissociation theory, creates flexible framework adaptable to individual client needs rather than rigid protocol. This flexibility proves essential because severely traumatized clients present uniquely, each requiring different configuration of interventions. Fisher’s emphasis on following the client’s process rather than imposing predetermined structure honors this individual variation.

For the trauma field more broadly, Fisher represents successful bridge between research and practice, between academy and consulting room. Her positions at Harvard Medical School and the Trauma Center gave her access to cutting-edge research. Her decades of clinical practice and consultation gave her grounding in what actually works with real clients. Her teaching brings these together, making sophisticated neuroscience accessible to practicing therapists while keeping clinical innovation accountable to empirical evidence.

Timeline of Janina Fisher’s Career and Major Contributions

1980: Begins treating individuals, couples, and families in private practice

1989: Attends Judith Herman’s grand rounds presentation, commits career to trauma treatment

1989-1990s: Predoctoral internship and early career development

1990s: Joins faculty at the Trauma Center founded by Bessel van der Kolk

1990s: Becomes instructor at Harvard Medical School

1990s-2000s: Develops expertise in treating complex trauma and dissociative disorders

Became past president of New England Society for the Treatment of Trauma and Dissociation

Became EMDR International Association Credit Provider

Became Assistant Educational Director of Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Institute

2015: Published Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment (with Pat Ogden)

2017: Published Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors: Overcoming Internal Self-Alienation

2020: Received ISSTD Lifetime Achievement Award

2021: Published Transforming the Living Legacy of Trauma: A Workbook for Survivors and Therapists

2022: Published The Living Legacy Instructional Flip Chart

Present: Executive Board member of Trauma Research Foundation

Present: Patron of the John Bowlby Centre

Present: International lecturer and consultant on trauma treatment

Present: Maintains private practice in Oakland, California

Complete Bibliography of Major Works by Janina Fisher

Fisher, J., & Ogden, P. (2015). Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Fisher, J. (2017). Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors: Overcoming Internal Self-Alienation. New York: Routledge.

Fisher, J. (2021). Transforming the Living Legacy of Trauma: A Workbook for Survivors and Therapists. Eau Claire, WI: PESI Publishing.

Fisher, J. (2022). The Living Legacy of Trauma Flip Chart: A Psychoeducational In-Session Tool for Clients and Therapists. Eau Claire, WI: PESI Publishing.

Fisher, J. (2017). Trauma-informed stabilization treatment: A new approach to treating unsafe behavior. Australian Psychologist, 3(1).

Fisher, J., Pain, C., & Ogden, P. (2006). A sensorimotor approach to the treatment of trauma and dissociation. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(1), 263-279.

Fisher, J. (2009). Self-harm and suicidality. Interact: Journal of the Trauma and Abuse Group UK, 9(2).

Fisher, J. (1999). Addictions and trauma. Paper presented at the 2000 Annual Conference of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation, San Antonio, Texas.

Influences and Legacy

Fisher’s work builds on Judith Herman’s foundational recognition that trauma symptoms reflect realistic responses to overwhelming events rather than intrapsychic fantasy. From Bessel van der Kolk, Fisher learned that the body keeps the score, that trauma treatment must engage somatic dimensions.

From Onno van der Hart, Ellert Nijenhuis, and Kathy Steele, Fisher adopted structural dissociation theory providing framework for understanding trauma’s fragmenting effects. From Pat Ogden, she integrated Sensorimotor Psychotherapy’s body-centered interventions. From Richard Schwartz, she adopted Internal Family Systems parts language and emphasis on Self.

Neuroscience research by Allan Schore on right brain affect regulation, Stephen Porges on polyvagal theory, and van der Kolk on trauma’s neurobiological effects provided empirical grounding. Attachment research informed understanding of how early relational trauma shapes capacity for self-regulation.

Fisher has profoundly influenced how therapists worldwide understand and treat complex trauma. Her accessible writing and teaching make sophisticated theory practical. Her integration of multiple approaches provides flexible framework adaptable to individual clients. Her emphasis on parts as protective adaptations rather than pathology reduces shame and increases therapeutic alliance.

Thousands of therapists have integrated her approaches into their practices, combining TIST principles with EMDR, brainspotting, psychodynamic therapy, and other modalities. Her work has particularly influenced treatment of eating disorders, addiction, self-harm, and suicidality, populations that often don’t respond to standard interventions.

For depth psychology, Fisher provides concrete methods for engaging complexes, integrating shadow material, and facilitating individuation. Her recognition that healing happens through relationship among parts rather than through interpretation or insight validates Jung’s emphasis on active imagination and symbolic work while grounding these processes neurobiologically.

0 Comments