The Dreamtime as a Cosmological Metaphor for the Human Psyche

The concept of the Dreamtime in Aboriginal Australian culture offers a profound and illuminating perspective on the nature of the human psyche. By exploring the parallels between the Dreamtime and psychological processes, we can gain a deeper understanding of the mind’s inner workings and the ways in which it creates and shapes our reality. This paper will delve into the idea that the Dreamtime serves as a cosmological metaphor for the psyche, where the gods are perpetually engaged in the act of creation, and how this concept relates to the human experience. Through an examination of the continuous process of creation, the sacred place of divine alchemy, portals to the Dreamtime, and the connection to the collective unconscious, we will uncover the rich insights that this Aboriginal Australian belief system offers for our understanding of the mind and its relationship to the world.

The Dreamtime as a Continuous Process of Creation

In Aboriginal Australian belief, the Dreamtime is not a static, one-time event but rather an ongoing process of creation. The gods, or ancestral beings, are constantly shaping and reshaping the world, performing the same actions over and over again, yet each time is unique and new. This idea of continuous creation bears a striking resemblance to the workings of the human psyche, which is perpetually engaged in the process of creating and interpreting reality.

Just as the gods in the Dreamtime are always in the act of creation, our minds are constantly processing information, forming memories, and generating thoughts and emotions. Each moment of consciousness is a new creation, a fresh interpretation of the world around us. In this sense, the Dreamtime can be seen as a metaphor for the psyche’s ceaseless creative activity.

The notion of the Dreamtime as a continuous process of creation has profound implications for our understanding of the human experience. It suggests that our perception of reality is not a passive reflection of an objective world but rather an active, ongoing construction of meaning. Our minds are not merely receptacles for sensory input but dynamic, creative agents that shape our experience of the world.

This idea is supported by recent findings in cognitive psychology and neuroscience, which have shown that the brain is constantly engaged in the process of predicting and interpreting sensory information based on prior experiences and expectations. Our perception of the world is not a direct, unfiltered representation of reality but rather a constructed narrative that is shaped by our beliefs, emotions, and memories.

The Dreamtime metaphor also highlights the importance of repetition and ritual in the process of creation. Just as the gods in the Dreamtime perform the same actions over and over again, our minds rely on repetition and habituation to create stable patterns of thought and behavior. Through the repetition of certain thoughts, emotions, and actions, we create neural pathways that shape our experience of the world and our sense of self.

However, the Dreamtime also emphasizes that each repetition is unique and new. This suggests that even as we engage in habitual patterns of thought and behavior, there is always the potential for novelty and transformation. Each moment of consciousness is an opportunity for fresh insights, new perspectives, and creative breakthroughs.

The Sacred Place of Divine Alchemy

The Dreamtime is described as a sacred place where the essence of the divine is continuously engaged in the process of creation. This concept of a sacred, inner space where transformation occurs is mirrored in the human psyche. The unconscious mind, in particular, can be seen as a place where the core of our being undergoes a constant process of change and growth.

In the Dreamtime, the actions of the gods are not mere repetitions but rather new and unique each time. Similarly, the psyche’s processes of transformation and self-discovery are always happening anew, even when dealing with familiar themes or issues. Each insight, each moment of growth, is a fresh creation born from the depths of the unconscious.

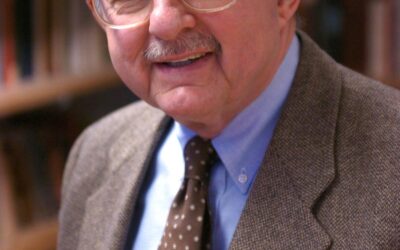

The idea of the unconscious as a sacred place of transformation has deep roots in Western psychology, particularly in the work of Carl Jung. Jung believed that the unconscious was not merely a repository of repressed memories and desires but rather a source of wisdom, creativity, and spiritual insight. He argued that by engaging with the symbols and archetypes of the unconscious, individuals could undergo a process of individuation, becoming more whole and self-aware.

The Dreamtime metaphor adds a new dimension to this idea by emphasizing the ongoing, dynamic nature of the unconscious. Rather than a static realm of hidden truths, the unconscious is seen as a place of constant creation and transformation, where the divine essence of the self is perpetually engaged in the act of self-discovery and self-expression.

This perspective has important implications for psychotherapy and personal growth. It suggests that the goal of therapy is not merely to uncover repressed memories or resolve past traumas but rather to facilitate an ongoing process of self-creation and self-actualization. By engaging with the symbols and archetypes of the unconscious, individuals can tap into a source of wisdom and creativity that is always available to them, even in the midst of life’s challenges and uncertainties.

The Dreamtime metaphor also highlights the importance of sacred space in the process of transformation. Just as the Dreamtime is a sacred realm separate from the mundane world, individuals may need to create sacred spaces in their own lives where they can engage with the depths of their being. This may involve practices such as meditation, prayer, or creative expression, which allow individuals to step outside of their everyday concerns and connect with a deeper source of meaning and purpose.

Portals to the Dreamtime

While the Dreamtime is seen as a separate realm from the mundane world, there are believed to be portals or access points between the two. In Aboriginal Australian culture, these portals are often associated with specific landforms and navigation routes called songlines. These songlines show where the mundane world and the Dreamtime intersect, revealing the presence of sacred forces that are continuously shaping reality.

In the context of the human psyche, these portals can be understood as moments of heightened awareness or insight, where the conscious mind connects with the deeper, more primal aspects of the self. These moments of connection can occur through various means, such as dreams, meditation, creative expression, or encounters with powerful symbols and archetypes.

The idea of portals to the unconscious has been explored by many Western psychologists, including Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. Freud believed that dreams were the “royal road to the unconscious,” providing a glimpse into the hidden desires and conflicts of the mind. Jung, on the other hand, saw dreams as messages from the unconscious, containing symbols and archetypes that could guide individuals towards greater self-awareness and wholeness.

The Dreamtime metaphor adds a new layer of meaning to these ideas by emphasizing the sacred nature of these portals. In Aboriginal Australian culture, songlines are not merely navigational aids but rather sacred paths that connect individuals to the creative force of the universe. Similarly, the portals to the unconscious can be seen as sacred thresholds that connect us to the divine essence of our being.

This perspective has important implications for how we approach dreams, creativity, and other forms of unconscious expression. Rather than dismissing these experiences as mere fantasies or distractions, we can view them as sacred opportunities for growth and transformation. By engaging with the symbols and images that emerge from the depths of our being, we can gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and our place in the world.

The Dreamtime metaphor also suggests that these portals are not limited to individual experiences but rather are woven into the fabric of the world itself. Just as songlines crisscross the Australian landscape, revealing the presence of sacred forces, the portals to the unconscious may be found in the symbols and stories that shape our cultural and spiritual traditions. By engaging with these collective symbols and narratives, we can tap into a deeper source of meaning and connection that transcends our individual lives.

The Dreamtime and the Collective Unconscious

The idea of the Dreamtime as a realm where gods and ancestral beings are constantly shaping reality bears a striking resemblance to Carl Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious. According to Jung, the collective unconscious is a shared, universal repository of symbols, archetypes, and mythic themes that influence human experience across cultures and throughout history.

Just as the gods in the Dreamtime are engaged in the ongoing creation of the world, the archetypes of the collective unconscious are constantly shaping our perceptions, emotions, and behaviors. By recognizing the parallels between the Dreamtime and the collective unconscious, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the ways in which universal themes and symbols shape our individual and collective experiences.

Jung believed that the archetypes of the collective unconscious were not merely abstract concepts but rather living, dynamic forces that could be encountered through dreams, myths, and other forms of symbolic expression. He argued that by engaging with these archetypes, individuals could undergo a process of individuation, becoming more whole and self-aware.

The Dreamtime metaphor adds a new dimension to this idea by emphasizing the sacred nature of the collective unconscious. In Aboriginal Australian culture, the Dreamtime is not merely a psychological construct but rather a spiritual reality that underlies the physical world. The gods and ancestral beings of the Dreamtime are not merely symbols or archetypes but living, creative forces that shape the world and our experience of it.

This perspective has important implications for how we understand the relationship between the individual and the collective. Rather than seeing ourselves as isolated beings, separate from the world and each other, we can recognize our deep connection to the creative forces that shape our reality. By engaging with the symbols and stories of the collective unconscious, we can tap into a source of wisdom and meaning that transcends our individual lives.

The Dreamtime metaphor also suggests that the collective unconscious is not a static, timeless realm but rather an ongoing process of creation and transformation. Just as the gods in the Dreamtime are constantly shaping the world anew, the archetypes of the collective unconscious are constantly evolving and adapting to the changing needs of humanity. By engaging with these archetypes, we can participate in the ongoing process of creation and contribute to the evolution of our collective consciousness.

This perspective has important implications for how we approach social and cultural change. Rather than seeing ourselves as passive recipients of cultural norms and values, we can recognize our agency in shaping the collective narratives that define our world. By engaging with the symbols and stories that emerge from the depths of the collective unconscious, we can work to create a more just, compassionate, and sustainable world.

Implications for Psychotherapy and Personal Growth

The insights offered by the Dreamtime metaphor have profound implications for psychotherapy and personal growth. By recognizing the parallels between the Dreamtime and the workings of the human psyche, therapists and individuals can gain a deeper understanding of the processes of transformation and self-discovery.

One of the key implications of the Dreamtime metaphor is the importance of engaging with the unconscious as a source of wisdom and creativity. Rather than seeing the unconscious as a mere repository of repressed memories and desires, therapists can help individuals to explore the symbols and archetypes that emerge from the depths of their being. By engaging with these symbols through techniques such as dream analysis, active imagination, and creative expression, individuals can tap into a source of inner guidance and transformation.

Another implication of the Dreamtime metaphor is the importance of recognizing the interconnectedness of all things. Just as the Dreamtime is a realm where all things are connected and interdependent, our individual lives are deeply interwoven with the lives of others and the world around us. By recognizing this interconnectedness, therapists can help individuals to develop a greater sense of empathy, compassion, and responsibility towards others and the environment.

The Dreamtime metaphor also highlights the importance of sacred space and ritual in the process of transformation. Just as the Dreamtime is a sacred realm separate from the mundane world, individuals may need to create sacred spaces in their own lives where they can engage with the depths of their being. This may involve practices such as meditation, prayer, or creative expression, which allow individuals to step outside of their everyday concerns and connect with a deeper source of meaning and purpose.

Finally, the Dreamtime metaphor suggests that the process of transformation is ongoing and never-ending. Just as the gods in the Dreamtime are constantly shaping the world anew, our own process of self-discovery and self-creation is a lifelong journey. By recognizing this, therapists can help individuals to embrace the challenges and uncertainties of life as opportunities for growth and transformation.

The Aboriginal Australian concept of the Dreamtime offers a rich and evocative metaphor for understanding the human psyche. By viewing the Dreamtime as a cosmological representation of the mind’s inner workings, we can gain insight into the ongoing process of creation and transformation that occurs within us. The idea of portals between the mundane world and the Dreamtime mirrors the moments of connection between the conscious and unconscious aspects of the self, highlighting the importance of accessing and integrating these deeper levels of awareness.

Furthermore, the parallels between the Dreamtime and the collective unconscious suggest that the mythic themes and symbols present in Aboriginal Australian culture may have universal resonance and significance. By exploring these connections, we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of the human experience and the ways in which our individual psyches are shaped by shared, archetypal forces.

The insights offered by the Dreamtime metaphor have profound implications for psychotherapy and personal growth. By recognizing the importance of engaging with the unconscious, recognizing the interconnectedness of all things, creating sacred space and ritual, and embracing the ongoing nature of transformation, therapists and individuals can work towards greater self-awareness, wholeness, and connection with the world around them.

Ultimately, the concept of the Dreamtime as a cosmological metaphor for the psyche invites us to view our inner lives as a sacred, ever-unfolding process of creation and discovery. By embracing this perspective, we can cultivate a deeper appreciation for the richness and complexity of our own minds and the ways in which they shape our experience of the world. As we navigate the challenges and uncertainties of life, we can draw upon the wisdom and creativity of the Dreamtime, recognizing our own role in the ongoing process of creation and transformation that underlies all existence.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jungian Thought to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

Main Ideas and Key Points:

Bibliography

- Berndt, R. M., & Berndt, C. H. (1988). The world of the first Australians: Aboriginal traditional life, past and present. Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Princeton University Press.

- Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams. Standard Edition, 4 & 5. London: Hogarth Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1959). The archetypes and the collective unconscious. Collected Works, 9(1). Princeton University Press.

- Jung, C. G. (1960). The structure and dynamics of the psyche. Collected Works, 8. Princeton University Press.

- Lawlor, R. (1991). Voices of the first day: Awakening in the Aboriginal dreamtime. Inner Traditions.

- Munn, N. D. (1973). Walbiri iconography: Graphic representation and cultural symbolism in a central Australian society. Cornell University Press.

- Stanner, W. E. H. (1979). White man got no dreaming: Essays 1938-1973. Australian National University Press.

- Tacey, D. (1995). Edge of the sacred: Transformation in Australia. HarperCollins.

- Tacey, D. (2000). ReEnchantment: The new Australian spirituality. HarperCollins.

- Tacey, D. (2009). Edge of the sacred: Jung, psyche, earth. Daimon.

- Tacey, D. (2013). Gods and diseases: Making sense of our physical and mental wellbeing. HarperCollins.

- Tonkinson, R. (1978). The Mardudjara Aborigines: Living the dream in Australia’s desert. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Wolfe, P. (1991). On being woken up: The Dreamtime in anthropology and in Australian settler culture. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 33(2), 197-224.

Further Reading

- Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world. Pantheon Books.

- Baruss, I. (2003). Alterations of consciousness: An empirical analysis for social scientists. American Psychological Association.

- Chalquist, C. (2007). Terrapsychology: Reengaging the soul of place. Spring Journal Books.

- Corbin, H. (1972). Mundus imaginalis, or the imaginary and the imaginal. Spring, 1-19.

- Grof, S. (1988). The adventure of self-discovery: Dimensions of consciousness and new perspectives in psychotherapy and inner exploration. SUNY Press.

- Hillman, J. (1975). Re-visioning psychology. Harper & Row.

- Ingerman, S. (1991). Soul retrieval: Mending the fragmented self. HarperCollins.

- Krippner, S., & Combs, A. (2002). The neurophenomenology of shamanism: An essay review. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 9(3), 77-82.

- Tacey, D. (2003). The spirituality revolution: The emergence of contemporary spirituality. Routledge.

- Tacey, D. (2006). How to read Jung. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Tacey, D. (2011). Gods and diseases: Making sense of our physical and mental wellbeing. HarperCollins.

- Tacey, D. (2015). Religion as metaphor: Beyond literal belief. Transaction Publishers.

- Tarnas, R. (2006). Cosmos and psyche: Intimations of a new world view. Viking.

- Walsh, R. (2007). The world of shamanism: New views of an ancient tradition. Llewellyn Publications.

- Winkelman, M. (2010). Shamanism: A biopsychosocial paradigm of consciousness and healing. Praeger.

Jungian Innovators

Topics

How do Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality Intersect?

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jungian Thought to Combat Addiction

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Jungian Analysts

Mythology, Anthro, Evopsych, Comparative Religion

Mystics, Philosophers and Gurus

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite

Spirituality

0 Comments