How 38 trillion bacteria are rewriting the rules of psychiatry—and what it means for trauma therapists, their clients, and the next decade of treatment.

The Second Brain We Forgot We Had

For over a century, psychiatry has operated on a simple premise: mental illness lives in the brain. Depression is a neurotransmitter imbalance. Anxiety is an overactive amygdala. Trauma is stored in neural circuits. Fix the brain, fix the mind.

This premise is not wrong. But it is radically incomplete.

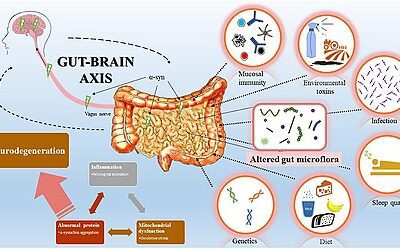

Emerging research reveals that the brain is not an isolated organ floating in cerebrospinal fluid, issuing commands to a passive body. It is one node in a vast communication network—and one of its most important conversation partners is the gastrointestinal tract. The gut contains over 100 million neurons, produces the majority of the body’s serotonin, and houses approximately 38 trillion bacterial cells that have co-evolved with humans over millions of years.

These bacteria are not passive hitchhikers. They are chemists—manufacturing neurotransmitters, modulating inflammation, and sending signals up the vagus nerve that directly influence mood, cognition, and stress response. The brain-gut connection, as Johns Hopkins Medicine describes it, is so profound that gastroenterologists now routinely treat anxiety and depression as part of managing digestive disorders.

For psychotherapists, this research doesn’t replace what we do. It deepens it. It explains why some clients remain treatment-resistant despite excellent therapeutic work. It offers new tools for the biopsychosocial model we’ve always championed. And it validates what somatic and experiential approaches have long intuited: that healing the mind requires attending to the body.

This article explores the science of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis (MGBA)—the emerging field that may transform mental health treatment over the next decade.

Part One: The Evolutionary Contract Between Microbes and Mind

An Ecosystem on a Leash

To understand why gut bacteria matter for mental health, we need to think evolutionarily. Humans did not evolve as isolated organisms. We evolved as ecosystems—hosts to trillions of microbial passengers that have been with us since before we were human.

Evolutionary biologists describe this relationship as an “ecosystem on a leash.” The host (human) has evolved sophisticated immune and physiological mechanisms to curate its microbial inhabitants—promoting beneficial symbionts while suppressing pathogens. But the relationship isn’t one-way. Microbes have evolved their own strategies to influence host behavior in ways that promote their survival and transmission.

This creates a constant evolutionary tension. The host wants microbes that provide metabolic and signaling benefits. The microbes want hosts that behave in ways that help them thrive and spread to new hosts.

Microbes and the Social Brain

One of the most provocative hypotheses in this field suggests that the microbiome helped drive the evolution of mammalian sociality. Because commensal bacteria require transmission between hosts to survive, they may have evolved chemical signals that encourage social interaction.

The evidence is striking. Germ-free mice—reared in sterile environments without a microbiome—display significant deficits in social behavior, repetitive behaviors, and altered communication. These phenotypes resemble Autism Spectrum Disorder in humans. Critically, reintroducing specific bacterial species can reverse these social deficits.

If specific bacteria are required for normal social development, then the precipitous loss of microbial diversity in modern populations—due to antibiotics, cesarean births, sterile environments, and processed diets—could be contributing to rising rates of social anxiety, autism spectrum presentations, and the epidemic of loneliness that therapists increasingly encounter.

The “Gut Sense”: An Ancient Warning System

The gut-brain axis likely evolved as a high-speed threat detection system. Long before humans had language or abstract thought, survival depended on the ability to detect pathogens in food before they could cause systemic infection.

The gut’s sensory network—comprising specialized cells and vagal nerve fibers—serves as a surveillance system, detecting “virulence factors” released by dangerous microbes. When these cells sense pathogenic signatures, they initiate rapid signaling to the brainstem, inducing avoidance behaviors, nausea, or anxiety.

This “gut sense” allows organisms to reject toxic food almost instantaneously. But here’s the clinical implication: dysregulation of this ancient threat-detection system may underlie modern anxiety disorders. When the gut microbiome is dysbiotic (imbalanced), it may constantly signal low-level threat to the brain, triggering chronic hypervigilance and stress responses even in the absence of actual danger.

Many clients describe a pervasive sense that “something is wrong” without being able to identify what. This may not be psychological defense or cognitive distortion—it may be their gut, accurately reporting that its microbial ecosystem is in distress.

Part Two: The Hardware of Gut-Brain Communication

Neuropod Cells: The Discovery That Changed Everything

For decades, scientists believed gut cells communicated with the brain solely through slow hormonal signaling—releasing chemicals into the bloodstream that eventually reached the brain over minutes to hours.

This view has been revolutionized by the discovery of neuropod cells—a specialized class of gut cells that possess axon-like projections forming direct synaptic connections with the vagus nerve. These cells don’t just release hormones; they use fast neurotransmitters (specifically glutamate) to send signals to the brain in milliseconds.

Research has demonstrated that neuropod cells can distinguish between the caloric value of sugar and the chemical structure of artificial sweeteners. Upon sensing glucose, they release glutamate to activate vagal fibers, which trigger dopamine release in the brain’s reward center within seconds.

The implications are profound. That “gut feeling” about a decision, that immediate sense of wrongness or rightness—these may be literal descriptions of neuropod signaling. The gut is not just digesting; it is perceiving, and communicating its perceptions to the brain faster than conscious thought.

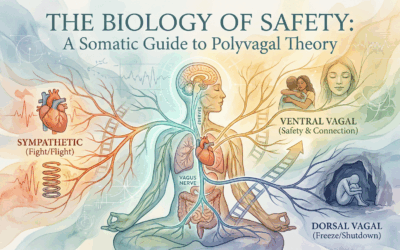

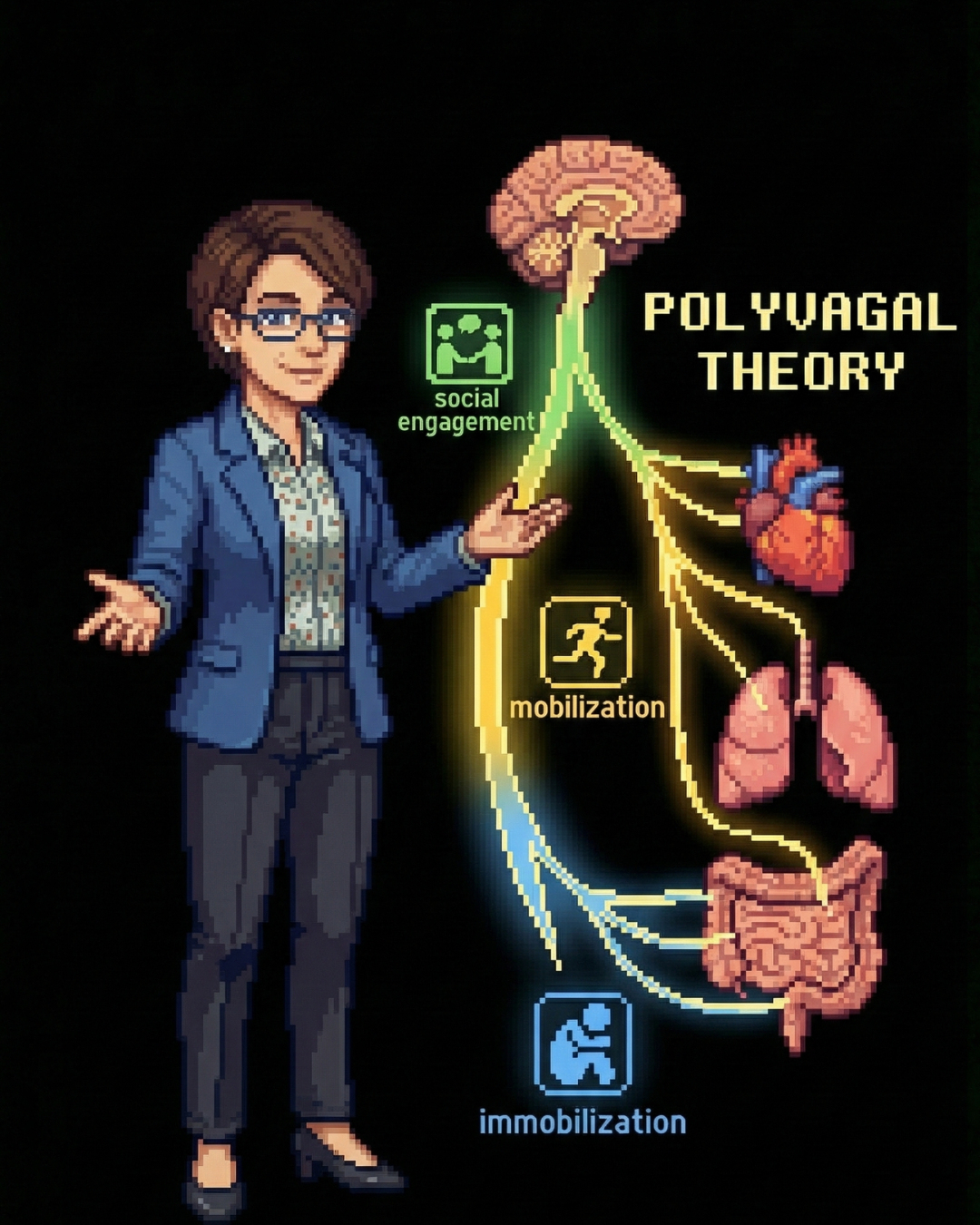

The Vagus Nerve: Information Superhighway

The vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X) is the primary conduit for gut-brain communication. Approximately 80-90% of vagal fibers are afferent—carrying sensory signals from the gut to the brain, rather than motor signals from brain to gut.

The vagus connects the gut to the Nucleus Tractus Solitarii (NTS) in the brainstem, which then projects to higher brain centers involved in emotion regulation—the hypothalamus, amygdala, and frontal cortex. This means gut signals have direct access to the brain’s emotional processing centers.

Research consistently demonstrates that low vagal tone is a biomarker for depression and poor stress resilience. Under chronic stress, vagal activity is inhibited, leading to increased gut inflammation. This inflammation signals the brain to induce depressive symptoms, creating a vicious cycle: stress inhibits the vagus → gut inflammation rises → inflammation signals depression → depression increases stress.

This is why body-brain approaches to trauma often emphasize vagal tone. It’s also why specific bacterial strains that activate vagal afferents—like Lactobacillus rhamnosus—produce measurable anxiolytic effects in both animal and human studies.

The Enteric Nervous System: The “Second Brain”

The gut contains over 100 million neurons—more than the spinal cord. This enteric nervous system (ENS) operates semi-independently, controlling digestion without requiring input from the brain. But it communicates constantly with the central nervous system and is highly sensitive to microbial metabolites.

The ENS is a major source of the body’s serotonin—approximately 90% of total serotonin is produced in the gut, not the brain. This is why SSRIs often cause gastrointestinal side effects, and why gut health and mental health are so intimately connected.

Dysfunction in the ENS is a hallmark of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), which is highly comorbid with anxiety and depression. By viewing the ENS as a peripheral emotional processing center, clinicians can begin treating anxiety “from the bottom up”—calming hyperexcitable enteric neurons using microbial metabolites, and thereby decoupling gut hypersensitivity from psychological distress.

Part Three: The Bacterial Pharmacopoeia

As the science matures, the focus is shifting from generic “probiotic” supplements to specific bacterial strains with defined mechanisms of action. These aren’t just “good bacteria”—they’re potential precision medicines targeting specific pathways in mental health.

Akkermansia muciniphila: The Barrier Guardian

Akkermansia muciniphila is a mucin-degrading bacterium that resides in the gut’s mucus layer. It has emerged as a keystone species for both metabolic and mental health.

Its primary mechanism involves strengthening the gut barrier by stimulating mucin production and increasing tight junction proteins. This prevents “leaky gut”—the translocation of inflammatory compounds like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) into the bloodstream. By reducing systemic inflammation, A. muciniphila prevents the cytokine-induced neuroinflammation increasingly implicated in depression.

Preclinical studies show that supplementation reverses stress-induced depressive behaviors and increases Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus. Recent research indicates it also modulates serotonin levels by affecting serotonin transporter expression in the colon.

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: The Anti-Inflammatory Powerhouse

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is one of the most abundant bacteria in the healthy gut, often constituting over 5% of total microbiota. Its depletion is a consistent biomarker in Major Depressive Disorder.

This bacterium produces butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid that acts as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor in the brain, promoting neuroplasticity. It also produces specific proteins that block the NF-κB inflammatory pathway, reducing production of cytokines like IL-6 that are often elevated in depression.

Perhaps most intriguingly, recent multi-omics studies have linked F. prausnitzii to the S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) cycle—a critical pathway for synthesizing dopamine and serotonin. Reduced F. prausnitzii abundance leads to impaired neurotransmitter synthesis through this mechanism.

Bacteroides fragilis: The Neurodevelopmental Modulator

Specific non-toxigenic strains of Bacteroides fragilis have shown remarkable efficacy in animal models of autism. In the Maternal Immune Activation mouse model, B. fragilis treatment corrected gut permeability and reversed repetitive behaviors and anxiety.

Critically, it restored levels of serum metabolites, specifically reducing 4-ethylphenylsulfate (4-EPS)—a neurotoxic compound that induces anxiety-like behaviors when administered to normal mice. This suggests a therapeutic strategy of “subtracting” harmful bacterial metabolites rather than just adding beneficial bacteria.

Bifidobacterium longum 1714: The Stress Response Regulator

Among currently available psychobiotics, Bifidobacterium longum 1714 is one of the most well-characterized in human clinical trials. In healthy volunteers, it has been shown to reduce cortisol output in response to acute stress and improve subjective sleep quality.

Neuroimaging studies demonstrated that this strain altered resting-state neural oscillations, specifically increasing theta band power in the frontal cortex—suggesting direct modulation of stress processing circuits. This is not placebo effect; this is measurable change in brain electrical activity from ingesting a specific bacterial strain.

Bacteria as Neurotransmitter Factories

Gut bacteria don’t just influence neurotransmitter levels indirectly—many species directly synthesize neurotransmitters:

GABA: Produced by Lactobacillus brevis, Bifidobacterium dentium, and others through decarboxylation of glutamate. GABA-producing bacteria dampen vagal sensory neuron excitability, reducing ascending stress signals.

Serotonin: While bacteria don’t make serotonin directly absorbable by the brain, spore-forming bacteria signal enterochromaffin cells to synthesize host serotonin, and regulate tryptophan availability for central serotonin production.

Dopamine: Species including Bacillus and Klebsiella pneumoniae produce L-DOPA and dopamine, potentially modulating the gut-brain reward circuit and influencing food cravings and motivation.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Produced by Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, and others. Butyrate inhibits HDACs (increasing BDNF), maintains blood-brain barrier integrity, and regulates microglial development.

Part Four: Clinical Implications for Psychotherapy

The “Bottom-Up” Approach to Treatment Resistance

For psychotherapists, this research validates what we’ve always known: the biopsychosocial model is not just a theoretical framework but a biological reality. It also offers an explanation for treatment resistance that doesn’t blame the client.

A client’s “resistance” to therapy may sometimes be biological—rooted in a dysbiotic gut that constantly sends alarm signals to the brain, perpetuating anxiety despite excellent cognitive behavioral work. You cannot think your way out of chronic neuroinflammation. You cannot process trauma effectively when your vagus nerve is signaling constant threat from the gut.

This doesn’t mean psychotherapy is ineffective. It means psychotherapy may need biological support. A trauma survivor whose gut microbiome was devastated by childhood stress, poor nutrition, or antibiotic overuse may need microbial restoration alongside Brainspotting or EMDR. The therapies work better when the biological substrate supports them.

Reframing Cravings and “Willpower”

The discovery that neuropod cells regulate sugar preference via dopamine pathways changes how we think about eating disorders and addiction. Binge eating may be driven by specific microbial populations utilizing the vagus nerve to signal for sugar—literally hijacking the reward system to feed themselves.

This reframes cravings as physiological signal hijacking rather than moral failing. For clients struggling with addiction or disordered eating, this understanding alleviates shame. Therapy can then focus on “re-training” the gut sensory system through nutritional changes that starve problematic populations while building beneficial ones.

Antibiotics as Developmental Trauma

Emerging research suggests that early life antibiotic exposure can permanently alter the gut-brain axis, potentially predisposing individuals to anxiety and depression. The microbiome is most vulnerable during the first three years of life, when it’s establishing itself and when neural development is most rapid.

This suggests therapists taking developmental histories should ask about antibiotic usage, cesarean birth, formula vs. breastfeeding, and gut health history. These may be biological insults that shaped the developing nervous system as surely as relational trauma.

A child who received multiple courses of antibiotics for ear infections may have had their stress-response system permanently altered—not through psychological experience but through microbial devastation. Understanding this doesn’t diminish the importance of psychotherapy; it contextualizes why some clients may need additional biological support.

The Inflammatory Phenotype of Depression

Not all depression is the same. Research increasingly distinguishes an “inflammatory phenotype”—patients with elevated inflammatory markers (CRP, IL-6) and reduced anti-inflammatory bacteria like F. prausnitzii. These patients may respond better to anti-inflammatory interventions (including specific psychobiotics) than to traditional SSRIs.

Future diagnostic approaches may include microbiome panels alongside standard psychiatric evaluation. A depressed client with high inflammation and low Faecalibacterium might receive targeted synbiotic intervention as first-line treatment, reserving SSRIs for those with different biological profiles.

This is the promise of Metabolic Psychiatry—viewing mental illness as fundamentally metabolic, with the microbiome as a key mediator. Pioneered by researchers like Dr. Shebani Sethi at Stanford Medicine, this approach treats conditions like bipolar disorder and treatment-resistant depression with metabolic interventions (including ketogenic diets) that work partly through microbiome modification.

Part Five: The Emerging Therapeutic Landscape

From Probiotics to Precision Psychobiotics

The supplement aisle “probiotic” is giving way to Precision Psychobiotics—defined bacterial strains with specific, validated mechanisms targeting mental health pathways. The difference is like that between “herbs” and pharmaceutical medications: specificity, standardization, and mechanistic understanding.

A major limitation of current probiotics is “colonization resistance”—foreign bacteria often can’t establish themselves in a hostile gut environment. The solution is Precision Synbiotics: pairing specific probiotic strains with the exact prebiotic fibers they need to survive. If F. prausnitzii requires specific galactooligosaccharides to thrive, researchers formulate products delivering both the organism and its preferred fuel—a “packaged ecosystem.”

Engineered Live Biotherapeutic Products

The future includes genetically engineering bacteria to act as intelligent drug delivery vehicles. Startups are developing strains modified to overproduce specific therapeutic molecules—secreting L-DOPA for Parkinson’s or 5-HTP for depression directly at the site of gut absorption, bypassing systemic side effects of oral medications.

Engineered bacteria could also serve as diagnostics—sensing inflammation markers in the gut and releasing therapeutic compounds in response to detected pathology. The gut becomes not just a treatment target but a treatment platform.

Digital Twins and Personalized Intervention

Given microbiome individuality, “trial and error” prescription is inefficient. The Institute for Systems Biology and others are developing “Digital Twins” of patients’ gut microbiomes—computational models that predict how a specific person’s microbiome will respond to different interventions.

By inputting metagenomic data and dietary patterns, clinicians could simulate whether a high-fiber diet would increase butyrate production in a particular depressed patient, or whether their microbiome lacks necessary fermenters and requires synbiotic intervention instead. Personalized medicine, at last, for the gut-brain axis.

Key Players in the Field

Several companies are actively translating this science into therapeutics:

Bloom Science is pioneering Live Biotherapeutic Products for neurological conditions by “reverse engineering” the ketogenic diet—identifying the specific bacterial strains responsible for its neuroprotective effects and delivering them orally without dietary restriction.

Holobiome targets the enteric nervous system directly, screening bacteria for their ability to produce specific neuroactive metabolites and developing defined consortia for depression and insomnia.

Kallyope focuses on gut-brain circuits involving neuropod cells and hormonal signaling, integrating single-cell sequencing with neural mapping to discover gut-restricted molecules that influence brain function.

Part Six: Practical Guidance for Clinicians and Clients

What Therapists Can Do Now

While precision psychobiotics are still emerging, clinicians can begin integrating gut-brain awareness into practice:

Expand history-taking: Ask about antibiotic history, birth method, early feeding, chronic digestive issues, and dietary patterns. These may be relevant biological context for mental health presentations.

Consider referrals: For treatment-resistant clients, consider referral to integrative medicine practitioners or gastroenterologists familiar with gut-brain research. Comprehensive stool testing can identify dysbiosis patterns.

Support dietary intervention: Frame nutrition as mental health intervention, not just physical health advice. Fiber feeds beneficial bacteria. Fermented foods introduce helpful organisms. Reducing processed foods starves problematic populations.

Validate somatic experience: When clients report “gut feelings” about situations, take these seriously as potential information rather than dismissing them as anxiety. The gut may be perceiving something real.

Contextualize cravings: Help clients understand intense food cravings as potential microbial manipulation rather than personal weakness. This reduces shame and opens possibilities for biological intervention.

What Clients Can Do Now

For individuals interested in supporting their gut-brain axis:

Prioritize fiber diversity: Different bacteria require different fibers. Eating a wide variety of plant foods (vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains) supports microbial diversity.

Include fermented foods: Yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and other fermented foods introduce beneficial bacteria and their metabolites. Aim for daily inclusion.

Minimize unnecessary antibiotics: Work with healthcare providers to ensure antibiotics are truly necessary. When antibiotics are required, consider probiotic support during and after treatment.

Reduce processed foods: Emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, and other additives in processed foods can damage the gut barrier and disrupt microbial balance.

Consider strain-specific supplements: If using probiotics, look for strain-specific products with research backing rather than generic “probiotic blends.” Bifidobacterium longum 1714 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG have human trial data for stress and anxiety.

Address underlying conditions: Chronic stress, poor sleep, and sedentary lifestyle all negatively impact the microbiome. Stress reduction practices support gut health alongside mental health.

Important Caveats

This field is evolving rapidly, and clinicians should maintain appropriate skepticism:

Not all probiotics are psychobiotics. Generic supplements may have minimal mental health effects. Strain specificity matters enormously.

Individual variation is massive. What works for one person’s microbiome may not work for another’s. Personalization will be key as the field matures.

The gut-brain axis doesn’t replace psychology. Biological intervention supports psychological work; it doesn’t substitute for it. Trauma still needs processing. Patterns still need understanding. Relationships still matter.

Beware commercial hype. As the market grows, so will unsubstantiated claims. Prioritize products and practitioners with rigorous scientific grounding.

Healing Begins in the Gut

The psychobiotic revolution represents a fundamental expansion of how we understand mental health. The brain is not a computer floating in isolation. It is an organ embedded in a body, in constant conversation with trillions of microbial partners whose evolutionary history predates human consciousness by billions of years.

For psychotherapy, this doesn’t diminish the importance of talk, relationship, and meaning-making. It adds another dimension. When a client can’t seem to escape anxiety despite insight and intervention, the answer may lie partly in their gut—in bacterial populations sending chronic alarm signals, in a vagus nerve silenced by inflammation, in a “second brain” perceiving constant threat.

The next decade will see the maturation of this field from fascinating hypothesis to clinical reality. Precision psychobiotics, engineered live biotherapeutics, digital twin modeling, and metabolic psychiatry will offer tools our predecessors couldn’t imagine. But the core insight is already actionable: the body keeps the score in more ways than we knew, and healing the mind may require, quite literally, healing the gut.

The bacteria that have co-evolved with us for millions of years are not passive passengers. They are partners in our mental health—partners we are only now learning to understand, and to consciously cultivate.

References and Further Reading

General Resources:

Johns Hopkins Medicine: The Brain-Gut Connection

Wikipedia: Enteric Nervous System

Peer-Reviewed Research:

PMC: The Evolution of the Host Microbiome as an Ecosystem on a Leash

PMC: Friends with Social Benefits: Host-Microbe Interactions as a Driver of Brain Evolution

PMC: Gut Microbiota Affects Brain Development and Behavior

PMC: Neuropod Cells: Emerging Biology of Gut-Brain Sensory Transduction

PMC: Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric Disorders

PMC: Akkermansia muciniphila in Neuropsychiatric Disorders

PMC: F. prausnitzii Potentially Modulates the Association Between Citrus Intake and Depression

PMC: The Microbiota Modulates Gut Physiology and Behavioral Abnormalities Associated with Autism

PMC: Bifidobacterium longum 1714 as a Translational Psychobiotic

PMC: The Correlation Between Gut Microbiota and Neurotransmitters

PMC: Precision Psychobiotics for Gut-Brain Axis Health

Clinical and Commercial Resources:

Stanford Medicine: Shebani Sethi on Metabolism and Mental Health

Institute for Systems Biology: Microbiome-Informed Precision Nutrition

0 Comments