Trauma, Memory, and the Spectral Geography of a Wounded Land

The Land That Refuses to Forget

Alabama is haunted. This is not a metaphor, or rather, it is not only a metaphor. Drive the back roads of the Black Belt at dusk and you will pass antebellum mansions where locals insist the piano plays itself. Stop at a bridge over any number of creeks in North Alabama and someone will tell you about the baby’s cry that echoes from the water. Descend into the industrial cathedral of Sloss Furnaces in Birmingham and security guards will warn you about the burned figure who pushes visitors from catwalks. The state maintains an almost embarrassing abundance of ghost stories, far exceeding what one might expect from demographic or geographic factors alone.

As a psychotherapist practicing in this landscape, I have come to understand that ghost stories are never really about ghosts. They are about the living. They are about what a community cannot metabolize, cannot integrate, cannot allow itself to forget. The spectral geography of Alabama is a map of unprocessed collective trauma, and reading it carefully reveals more about the psychology of place and memory than any conventional history.

This article is an attempt to understand why Alabama haunts itself with such persistence and specificity. What psychological functions do these stories serve? What do they reveal about grief, guilt, identity, and the stubborn refusal of the past to stay buried? And what might it mean for those of us who live among these ghosts, whether we believe in them or not?

The Architecture of Haunting

What Makes a Place “Haunted”?

Before examining specific Alabama legends, we must establish a psychological framework for understanding haunting itself. From a purely materialist perspective, ghosts do not exist. Yet the experience of haunting is universal across human cultures, which suggests that “ghostliness” corresponds to something real in human psychology, even if that something is not a disembodied spirit.

Environmental psychologists have identified several factors that predispose a location to be perceived as haunted. These include ambiguous sensory stimuli (creaking floors, drafts, shadows), historical associations with death or violence, architectural features that create feelings of enclosure or surveillance, and cultural priming through stories and legends. But these factors describe the conditions under which haunting is perceived, not why certain places accumulate ghost stories while others do not.

The deeper answer lies in what we might call “unfinished psychological business.” A place becomes haunted when something happened there that the community has not adequately processed. The ghost is the return of the repressed, manifesting spatially rather than intrapsychically. It is the thing we cannot talk about directly, showing up in the corner of our vision.

The Indigenous Substratum and the Psychology of Displacement

Cosmology as Container

The Indigenous peoples of Alabama, primarily the Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, and Alibamu, possessed sophisticated cosmological systems that served as containers for psychological experience. The tripartite cosmos of Upper World (order, avian spirits), Lower World (chaos, serpentine entities), and Middle World (the human plane) provided a framework for understanding suffering, danger, and the uncanny.

Consider the Tie-Snake of Muscogee tradition, a powerful underwater serpent that ensnares victims and drags them into the depths. From a psychological perspective, the Tie-Snake is a perfect externalization of the experience of being “pulled under” by forces beyond one’s control. Depression, addiction, grief, the undertow of circumstance: all of these find symbolic representation in the creature that wraps around you and pulls you down. The legend does not eliminate the danger but provides a narrative structure for understanding it.

Similarly, the Horned Serpent (Uktena to the Cherokee, Sint Hollo to the Choctaw) represents the terrifying power of chaos and transformation. The blazing crystal in its forehead offers immense power to anyone who can obtain it, but the attempt means confronting the most dangerous force in the cosmos. This is a story about the attraction of forbidden knowledge, about the price of power, about the hero’s journey into the underworld of the psyche.

These cosmological entities are not “hauntings” in the sense of unquiet dead. They are something more fundamental: acknowledgments that the world contains forces that exceed human comprehension and control. The psychological function is humility. In a cosmos populated by Tie-Snakes and Horned Serpents, human beings cannot afford the narcissistic fantasy that they are masters of their environment.

The Stikini and the Horror of Hidden Evil

Among the most psychologically complex Indigenous entities is the Stikini (also Stigini or Ishtikini), known primarily from Seminole and Creek traditions but rooted in the Alabama region before displacement. The Stikini is not a spirit or a god but a human being who has become something monstrous through the practice of witchcraft.

The transformation process is viscerally disturbing. By day, the Stikini appears as an ordinary member of the community, often an elder or someone of unassuming status. By night, the witch vomits up their internal organs, hiding them in the underbrush or hanging them in Spanish moss. This biological inversion hollows out the body, allowing transformation into a great horned owl. In this form, the Stikini hunts humans, specifically craving human hearts, which it consumes to extend its unnatural lifespan.

The psychological resonance of this legend is profound. It articulates a universal anxiety: that evil can wear a familiar face, that someone in our community may be fundamentally other than they appear. The image of vomiting out one’s organs is a somatic metaphor for the corruption of self that occurs when a person abandons communal values for predatory individualism. The Stikini looks like us but has literally emptied itself of humanity.

The vulnerability of the Stikini is equally instructive. Because the witch must re-ingest its organs before sunrise to return to human form, the hero can defeat it by finding and destroying the hidden viscera. Evil, however powerful, has a physical anchor. It can be defeated through vigilance and the willingness to look where the monster does not want you to look. This is a template for addressing hidden corruption: find what has been concealed, expose it to light, and the transformation cannot be completed.

The taboo against speaking the Stikini’s name in many traditional communities reflects an understanding that attention has power. To name the thing is to invite it, to participate in its reality. This is not superstition but sophisticated psychology. We know from trauma research that hypervigilance to threat can itself become pathological, that obsessive attention to danger creates the very anxiety it seeks to prevent. The speech taboo is a cultural technology for managing this paradox.

The Nunnehi and the Trauma of Removal

The Nunnehi (or Nûñnë’hï), the “People Who Live Anywhere” of Cherokee tradition, occupy a different psychological register entirely. These are not predators but protectors, immortal spirit-folk who reside in invisible townhouses inside mountains, under mounds, and beneath riverbeds. They are fond of music and dancing, and they are known to rescue lost travelers, feeding them in their subterranean halls.

The temporal dynamics of the Nunnehi world are significant. A human who spends what feels like a single night in a Nunnehi townhouse may return to find that weeks, months, or even years have passed. This time-dilation motif marks the Nunnehi realm as a place of eternal stasis, untouched by the decay and violence of the mortal world. It is, in psychological terms, a fantasy of escape from time itself.

This dimension of the legend became achingly poignant during the Trail of Tears. As federal troops rounded up Cherokee families for forced deportation to Oklahoma, stories circulated of groups who chose a different path. Rather than submit to the march, they fasted and prayed until the Nunnehi opened the doors to their mountain townhouses. These Cherokee walked into places like Pilot Knob and were never seen again, transformed into spirits, joining the Nunnehi forever.

From a psychological perspective, this is a narrative of resistance through transcendence. The physical removal could not be prevented; the political reality was overwhelming. But the stories insist that some refused to leave, that the connection between the Cherokee and their land was so profound that it could be preserved through spiritual transformation. The “disappeared” are not dead but translated to another plane of existence. They remain in Alabama, watching, waiting, perhaps one day to return.

This is the psychology of traumatic loss refusing to accept its finality. It is the bereaved parent who senses their child’s presence in the empty room, the widow who feels her husband’s hand on her shoulder. These experiences are not delusions but expressions of a love that cannot accept the absolute severing of connection. The Nunnehi legends perform the same function at a collective scale, preserving in story what was destroyed in history.

Sites like Manitou Cave near Fort Payne, which contains Cherokee syllabary inscriptions recording ceremonial activities during the removal crisis, function as liminal spaces where this connection remains accessible. Modern visitors often describe the cave as a “thin place,” a location where the boundary between worlds feels permeable. The ghosts here are not frightening but sorrowful, the residue of a people’s refusal to fully leave.

The Choctaw Emergence and the Psychology of Autochthony

The Choctaw emergence myth offers yet another psychological dimension. Unlike tribes who claim migration from the west or north, the Choctaw assert that their people were born from the earth itself, emerging from a great cave near the Nanih Waiya mound, damp and unformed, drying themselves on the mound’s slopes.

This autochthonous origin creates a psychological bond between people and land that differs fundamentally from the settler-colonial relationship. The Choctaw are not inhabitants of the land; they are biological extensions of it. Removal therefore was not merely displacement but dismemberment, a severing of the umbilical connection between people and their literal mother.

The Bohpoli (“Throwers”), mischievous Little People who guard the area around Nanih Waiya by throwing rocks at intruders, serve as supernatural custodians of this sacred geography. They ensure that the site of emergence remains inviolate, that the birthplace is not profaned. Their persistence in folklore represents the ongoing vitality of the origin bond, the insistence that the connection has not been fully severed despite the violence of history.

The Psychological Function of Indigenous Haunting

Taken together, the Indigenous supernatural traditions of Alabama perform several psychological functions. They establish humility before forces greater than human will. They provide frameworks for understanding hidden evil and the corruption of community members. They preserve, in symbolic form, the bond between people and land that historical violence attempted to destroy. And they offer templates for resistance that operate at the level of story when physical resistance has been made impossible.

These are not “ghost stories” in the sense that the later European-American traditions are ghost stories. They are something older and in some ways more psychologically sophisticated: acknowledgments that the world exceeds human comprehension, that place has memory, and that some bonds cannot be broken even by death or displacement.

The Antebellum Shadow and the Anxiety of the “Good Death”

The Planter Class and Its Monuments

The ghost stories of Alabama’s Antebellum period are overwhelmingly associated with the planter aristocracy and their architectural achievements. Gaineswood in Demopolis, the Drish House in Tuscaloosa, Sturdivant Hall in Selma, Sweetwater Mansion in Florence: these are not humble dwellings but Greek Revival monuments, built to proclaim the wealth and permanence of their owners. That they are now primarily known as “haunted houses” tells us something important about the psychology of the period and its aftermath.

The plantation economy was a system of profound moral contradiction. Men and women who considered themselves civilized, Christian, and honorable built their lives on the systematic brutalization of enslaved people. This cognitive dissonance required elaborate psychological defenses, including the development of what historians call the “paternalist ideology,” which held that enslavement was actually beneficial to the enslaved.

When a psychological defense is this elaborate, it is also this fragile. The haunted plantation represents the return of what the defense sought to repress: the knowledge that the system was fundamentally unjust, that the wealth was built on suffering, that the “refinement” was facade over cruelty. The ghosts of the antebellum South are almost never the enslaved themselves (that would be too direct an accusation), but rather the planter class, trapped in their monuments, unable to move on.

Gaineswood and the “Bad Death”

The legend of Evelyn Carter at Gaineswood in Demopolis exemplifies the psychological dynamics of antebellum haunting. Evelyn was a young woman from Virginia who traveled to Alabama to serve as governess for General Nathan Whitfield’s children. She was known for her beauty and her skill at the piano. The tragedy unfolded in predictable Southern Gothic fashion: a failed courtship with a French count, declining health, and death during a harsh winter far from home.

The psychological crux of the legend lies in the “broken vow.” Evelyn had extracted a promise that, should she die, her body would be returned to Virginia. When she succumbed to illness, the rivers were frozen or flooded, making transport impossible. Whitfield, attempting to preserve her body until spring, sealed her in a pine coffin and stored it under the main staircase of his home.

This detail is crucial. The corpse of Evelyn Carter was kept in the living space of the house, present but not properly processed, neither buried nor returned. This is a nearly perfect metaphor for unresolved grief. The phenomena reported at Gaineswood, piano music in the empty parlor, the rustle of silk skirts in hallways, footsteps near the staircase, are the sensory correlates of what happens when death is not fully acknowledged.

The anthropologist Robert Hertz wrote extensively about the concept of the “double burial” in traditional societies, in which the initial disposal of the corpse is followed by a secondary ritual that marks the full transition of the deceased to the world of the dead. The failure to complete this transition creates what Victor Turner called a “liminal” state, in which the dead person is neither fully present nor fully absent. Evelyn Carter, stored under the staircase, is the liminal dead made literal.

The “bad death,” in 19th-century Southern culture, was not merely physical suffering at the end of life. It was death away from home, death without family present, death without proper burial in ancestral soil. The obsessive concern with “dying well” reflected a theology in which the manner of death shaped eternal destiny, but it also reflected a psychological reality: we need ritual to process loss, and when ritual fails, the loss remains unprocessed.

Evelyn Carter haunts Gaineswood not because she is evil or vengeful but because she was not properly released. Her ghost is the persistence of grief, the ongoing presence of what should have been laid to rest. The haunting will continue, the legend implies, until the original promise is somehow fulfilled, until she is finally “home.”

The Drish House and the Ritual Obsession

If Gaineswood represents the failure of burial ritual, the Drish House in Tuscaloosa represents obsession with ritual taken to pathological extremes. Dr. John Drish was a wealthy physician and enslaver whose addiction to alcohol led to his death in 1867, reportedly from a fall down the stairs during delirium tremens. His widow, Sarah, became fixated on the candles used at his wake. She preserved them meticulously and extracted a promise from her family that these specific candles would be burned at her own funeral.

When Sarah Drish died years later, the candles could not be found. The violation of her final ritualistic command is said to have ignited the haunting, which manifests as phantom fire in the third-story tower of the mansion. Fire crews have been dispatched to extinguish blazes that do not exist.

From a psychological perspective, Sarah Drish’s behavior reflects a common response to traumatic loss: the attempt to control the uncontrollable through ritual. Her husband’s death was sudden, violent, and humiliating (the delirium of alcoholism was a shameful end for a man of his class). By focusing obsessively on the candles, Sarah created a sense of agency in the face of overwhelming helplessness. If she could only ensure that the right candles were burned at the right time, some order could be imposed on the chaos of mortality.

This is magical thinking in the clinical sense, the belief that ritual actions can influence outcomes through non-causal mechanisms. It is extraordinarily common in grief, particularly in the early stages when the reality of the loss has not fully been integrated. Parents of deceased children often preserve their rooms exactly as they were. Widows wear wedding rings decades after their husbands’ deaths. These behaviors are not pathological; they are ways of maintaining connection with the lost object while the psyche gradually adjusts to the new reality.

What makes Sarah Drish’s case remarkable is the posthumous consequence of ritual failure. The phantom fire is her rage at being denied the completion she sought, the closing of the circle, the reunification with her husband through the symbolic burning of the wake candles. The fire is both accusation (you failed me) and signal (I am still here, still waiting). It transforms the house itself into a beacon of unfulfilled promise.

Sturdivant Hall and the Trapped Spirit

John Parkman’s ghost at Sturdivant Hall in Selma adds economic dimension to the psychology of antebellum haunting. Parkman was a banker who engaged in cotton speculation and embezzlement during the chaos of Reconstruction. As his financial empire collapsed, he was arrested and imprisoned. During an escape attempt at the river, he was killed, either by drowning or by gunfire.

The psychological significance of the Parkman legend lies in his vow: he swore never to leave Sturdivant Hall until his name was cleared. His ghost reportedly manifests as footsteps on the second floor, doors opening and closing of their own accord, and the apparition of a man in 19th-century dress standing on the balcony.

This is the ghost as prisoner. Parkman is not merely unquiet; he is trapped. His crime stained his name, and until that stain is removed, he cannot leave the site of his former glory. The haunting perpetuates the narrative of the “ruined man,” a figure central to Southern self-understanding in the Reconstruction period. The proud aristocrat brought low by circumstances beyond his control (or, more honestly, by his own corruption), forever pacing the halls of what he has lost.

The psychological function of this legend is complex. On one hand, it provides a cautionary tale about financial overreach and moral failure. On the other hand, it preserves sympathy for the ruined aristocrat, suggesting that his punishment (eternal imprisonment in his own home) is excessive, that he deserves to be freed. The legend keeps Parkman’s case “open,” refusing the closure of either condemnation or forgiveness.

The Face in the Window and the Indelible Stain

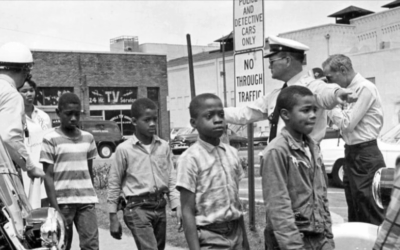

The legend of Henry Wells at the Pickens County Courthouse in Carrollton offers something unprecedented in Alabama haunting: physical evidence. Wells was a Black man (formerly enslaved or freedman, depending on the account) accused of burning down the courthouse in 1878. A lynch mob gathered outside the new courthouse where he was being held in the garret. As Wells looked out at the mob, a bolt of lightning struck nearby. The legend claims that the flash photographed or etched Wells’ terrified face onto the glass pane of the window.

Despite attempts to wash the pane with acid or replace it entirely, the face allegedly persists. It gazes down from the seat of justice, a permanent witness to the community’s history of extrajudicial violence.

This is haunting as accusation. Unlike Evelyn Carter or Sarah Drish, Henry Wells was not a member of the planter class whose ghost reflects the anxieties of that class. He was a victim of the racial terror that defined post-Reconstruction Alabama. His face in the window is a “moral stain” made visible, an external marker of the community’s guilt that cannot be cleaned away.

From a psychological perspective, the legend serves multiple functions. For those who believe in Wells’ innocence, the face is a demand for justice, a refusal to let the crime be forgotten. For those who participated in or descend from participants in lynch culture, the face is an externalization of guilt, a projection of the conscience onto the physical environment. Either way, the legend insists that certain acts create permanent consequences, that some stains cannot be removed.

The persistence of the face despite attempts at removal is psychologically significant. It suggests that the guilt is not merely individual but collective, not merely historical but ongoing. Each generation that fails to fully reckon with the legacy of racial violence refreshes the stain. The face will remain, the legend implies, until that reckoning occurs.

The Psychological Function of Antebellum Haunting

The antebellum ghost stories share several psychological features. They are overwhelmingly concerned with death and burial ritual, reflecting the 19th-century obsession with the “good death.” They locate haunting in the monuments of the planter class, transforming symbols of wealth and power into prisons for the restless dead. They express guilt that cannot be directly acknowledged, whether the guilt of displacement (Evelyn Carter), of failed promise (Sarah Drish), of financial corruption (John Parkman), or of racial violence (Henry Wells).

These ghosts do not resolve. They persist, year after year, generation after generation. The psychological work they represent, the processing of loss, the acknowledgment of guilt, the completion of interrupted ritual, remains undone. The houses remain haunted because the histories remain unmetabolized.

Industrial Phantoms and the Violence of Progress

The New South and Its Discontents

Birmingham was founded in 1871, six years after the end of the Civil War, at the intersection of railroad lines in a valley rich with iron ore, coal, and limestone. It was designed to be the center of a “New South” that would industrialize, modernize, and move beyond the agrarian economy of the plantation. The city’s nickname, “The Magic City,” reflected the astonishing speed of its growth.

But magic has its costs. The pig-iron industry that built Birmingham was extraordinarily dangerous. Workers, many of them African American convicts leased to industrial operators under a system that historians have called “slavery by another name,” faced furnace temperatures exceeding 2,000 degrees, inadequate safety equipment, and foremen who prioritized production quotas over human life. The “magic” was paid for in blood.

The ghost stories of industrial Birmingham reflect this reality. They are not stories of aristocrats trapped in mansions but of workers killed on the job, their deaths unreported or minimized, their bodies sometimes literally consumed by the industrial process. These are working-class ghosts, and their psychology is the psychology of exploitation and resistance.

Sloss Furnaces and the Composite Monster

Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark is widely cited as one of the most haunted industrial sites in the United States. The central figure of the Sloss mythology is James “Slag” Wormwood, a foreman who allegedly operated the furnaces in the early 20th century. Wormwood, the legend states, was sadistic. He pushed his “graveyard shift” crew to dangerous extremes to increase production. His workforce consisted largely of African American convicts (through the convict-leasing system) and desperate immigrants.

In 1906 (dates vary in the folklore), Wormwood plummeted from the catwalk into the molten iron of “Big Alice” (Blast Furnace No. 1). The legend strongly implies this was not an accident but an act of collective retribution by his abused workers. His body was instantly incinerated.

Since his death, and continuing after the furnaces closed in 1971, visitors report violent paranormal activity: being pushed from behind on the catwalks, hearing the command “Get back to work,” seeing a horrifying apparition with badly burned skin.

The psychology of the Slag Wormwood legend is complex. “Wormwood” is almost certainly a composite folkloric character rather than a historical individual. The name itself is allegorical (wormwood being the bitter herb associated with suffering in the Bible). He represents the “bad boss,” the exploiter who treats workers as disposable, the human face of industrial capitalism’s indifference to individual life.

His death by molten iron is poetic justice. The substance that he forced men to produce at risk of their lives becomes the instrument of his destruction. The workers who killed him (if they did) are anonymous, collective, and unpunished. The legend preserves a fantasy of worker agency in a system designed to deny it.

But the haunting does not end with Wormwood’s death. His ghost continues to terrorize, still commanding workers to their labor, still pushing people from catwalks. This suggests that killing the individual exploiter does not end exploitation. The system persists beyond any individual perpetrator. The ghost of Slag Wormwood is the ghost of industrial capitalism itself, demanding production even from beyond the grave.

Historical records confirm that the danger at Sloss was genuine. Workers like Theophilus Jowers in 1887 fell into the furnaces and were consumed, leaving only calcified bones and ash. The Sloss hauntings are a spectral manifestation of what was erased from the triumphalist narrative of the Magic City: the human cost of industrial progress.

The Eliza Battle and the Maritime Disaster

On March 1, 1858, the luxury paddle steamer Eliza Battle was traveling down the Tombigbee River, laden with over 1,200 bales of cotton and wealthy passengers. On a freezing, stormy night, the cotton ignited. The fire spread rapidly, forcing passengers into the icy, flooded river. Thirty-three people died, many freezing to death in the trees along the riverbank where they had sought refuge from the water.

The phantom ship that haunts the Tombigbee is not merely a replay of the disaster. It is an active omen. River lore states that on cold, stormy nights in late winter, the Eliza Battle appears on the water, fully engulfed in spectral flames. The sound of the calliope and the screams of the dying echo across the water. Sighting the ship is a harbinger of disaster for those on the river.

This is the “ghost ship” archetype, found in maritime cultures worldwide. From the Flying Dutchman to the Ghost Kayak of the Inuit, phantom vessels serve as warnings, manifestations of the sea’s (or river’s) power to destroy human enterprise. The psychological function is cautionary: the water is dangerous, the storms are real, the fire can come for you too.

But the Eliza Battle legend has a specific historical dimension. The ship was carrying cotton, the economic engine of the antebellum South. The passengers were wealthy planters and merchants. The disaster struck at the height of the plantation economy, just three years before the Civil War would begin the destruction of that world. The phantom ship is a premonition not just of individual death but of systemic collapse, a burning symbol of the entire order that would soon go up in flames.

The Temple of Sibyl and the Eccentric Elite

George Ward, who served as mayor of Birmingham for over a decade in the early 20th century, was a classical enthusiast who built an estate called “Vestavia” modeled after the Temple of Vesta in Rome. On the edge of his mountain property, he constructed an open-air gazebo, the Temple of Sibyl, which he intended as his tomb. Ward wished to be buried in a cave beneath this temple, surrounded by the birds he had protected in his private sanctuary.

Upon his death in 1940, local laws prohibited burial outside consecrated cemeteries. Ward was interred at Elmwood Cemetery, far from his beloved temple. The Temple of Sibyl was later moved to a roadside park in what is now the suburb of Vestavia Hills.

The haunting of the temple, reported as cold spots and feelings of surveillance, follows the pattern established by Evelyn Carter, Sarah Drish, and the other “displacement ghosts” of the antebellum period. Ward’s spirit cannot rest because his specific, idiosyncratic burial wishes were not honored.

But Ward’s case differs from the earlier legends in its secularism. He was not concerned with Christian burial or family plots but with a pagan aesthetic, a desire to be entombed like a Roman rather than a Christian. His ghost represents the persistence of heterodox desire, the demand for individual self-expression that exceeds the conformist expectations of Southern society. Even in death, George Ward refuses to be ordinary.

Dead Children’s Playground and the Innocence Lost

In Huntsville, the “Dead Children’s Playground” occupies a limestone bowl of a former quarry within Maple Hill Cemetery, adjacent to the oldest sections of graves. The legend connects the playground to the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, which claimed many children’s lives. The ghosts are not frightening but poignant: the sound of children’s laughter echoing off the quarry walls, orbs of light floating near the equipment, and most distinctively, the swing sets moving by themselves, swaying in unison or in specific patterns without any wind.

The psychology of child ghost legends is distinctive. Unlike adult ghosts, who typically represent unfinished business, resentment, or unfulfilled vows, child ghosts almost always represent loss itself, pure and unadorned. The dead children of the playground are not angry; they are simply playing, continuing in death what they were denied in life.

The moving swings are particularly evocative. The swing is an object of childhood joy, of the physical sensation of flying, of the parental push that sends the child soaring. Empty swings that move on their own suggest invisible children at play, but also invisible parents pushing, the continuation of care beyond death. The legend is not frightening but elegiac, a commemoration of what was lost to epidemic disease.

The Spanish Flu of 1918 killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, including many children. The trauma of this loss was largely unprocessed, overshadowed by the end of World War I and the cultural pressure to “return to normalcy.” The Dead Children’s Playground preserves the grief that was not adequately mourned, giving it spatial location and ongoing presence.

The Psychological Function of Industrial and Modern Haunting

The ghost stories of industrial and modern Alabama serve different functions than their antebellum predecessors. They are less concerned with burial ritual and aristocratic honor, more concerned with the violence of economic systems and the randomness of disaster. They acknowledge that modernity has not eliminated haunting but merely changed its character.

Slag Wormwood represents systemic exploitation that persists beyond individual perpetrators. The Eliza Battle represents the vulnerability of human enterprise to natural and mechanical catastrophe. George Ward represents the persistence of individual desire against social conformity. The Dead Children’s Playground represents the collective grief of epidemic loss. Together, they map the psychological costs of progress, the ghosts that accumulate as the Magic City grows.

Cryptids, Wilderness Entities, and the Fear of the Unknown

The Persistence of Monsters

Alongside the ghosts of the dead, Alabama harbors another category of supernatural entity: the cryptid, the creature that should not exist but is repeatedly reported. The “White Thang” of Morgan, Etowah, and Winston counties; the Coosa River Monster; the creatures of Bear Creek Swamp: these are not spirits of the deceased but something else entirely, anomalies in the natural order that refuse categorization.

Cryptid legends serve a psychological function distinct from ghost stories. Ghosts are about the past, about what refuses to stay dead. Cryptids are about the present, about the limits of our knowledge, about the terrifying possibility that the world contains more than we have mapped.

The White Thang and the Albino Aberration

The “White Thang” has been reported in north-central Alabama since at least the 1930s. Descriptions vary, but consistent elements include a height of seven to eight feet, coverage in white hair (sometimes described as sleek or slick rather than shaggy), and a terrifying vocalization that mimics a woman in distress or a crying baby.

The whiteness of the creature is its most psychologically significant feature. In the deep green and brown of the Alabama woods, a stark white creature is an aberration, a violation of camouflage expectations. Albinism in animals is real and relatively common, but it is also associated with vulnerability (the albino animal stands out to predators) and with folklore traditions that mark the albino as supernatural or cursed.

The mimicry of human distress sounds links the White Thang to predator legends found worldwide. Many cultures warn of creatures that imitate human voices to lure victims. The psychology is clear: the creature exploits human compassion, the instinct to help someone in distress, turning it into a trap. This is a cautionary tale about the danger of responding to cries in the wilderness, of venturing off the path to help what might not be human at all.

Bear Creek Swamp and the Transgressive Ritual

Bear Creek Swamp in Autauga County combines classic folklore with modern “creepypasta” sensibilities. The core legend is a variation of the “La Llorona” motif found throughout the Americas: a mother wandering the swamp in endless search for her lost child. The ritual for interaction involves the chant “We have your baby,” repeated three times. This provocation allegedly causes physical attack by the spirit or a terrifying scream.

In 2014, the folklore gained a physical dimension when the Autauga County Sheriff’s Office discovered 21 porcelain dolls mounted on bamboo stakes in the swamp waters. Some dolls had their faces painted or disfigured. While authorities concluded it was likely a prank, the discovery reinforced the swamp’s reputation for ritualistic strangeness.

The psychology of the Bear Creek legend is about the violation of maternal bonds. The wandering mother is a figure of perpetual grief, unable to complete the search that defines her existence. The ritual provocation (“We have your baby”) is deliberately cruel, exploiting her loss to generate supernatural response. The dolls, whether placed as art installation, prank, or genuine ritual, physicalize the legend’s concerns with childhood, simulacra, and the line between the real and the symbolic.

The Psychological Function of Cryptids and Wilderness Entities

Cryptids and wilderness entities serve as reminders that the world exceeds human knowledge and control. In an era of satellite mapping and GPS tracking, of ecosystem management and wildlife biology, the cryptid insists that something remains unknown. The forest still holds secrets. The swamp still harbors mysteries. We have not mastered the natural world as completely as we like to believe.

This is psychologically valuable. The fantasy of total knowledge is also the fantasy of total control, and total control is a form of death, the elimination of surprise, possibility, and wonder. The cryptid preserves wildness, not just in the ecological sense but in the psychological sense of the wild mind, the imagination that exceeds what has been cataloged.

Folk Figures and the Elevation of the Historical

When History Becomes Legend

Alabama folklore includes several figures who were historical persons but have been elevated to supernatural status through the accumulation of legend. Railroad Bill (Morris Slater), Granny Dollar (Nancy Dollar), and Hugging Molly represent this process of apotheosis, by which the extraordinary human becomes the supernatural entity.

Railroad Bill and the Conjure of Resistance

Morris Slater, known as Railroad Bill, was a real African American outlaw who operated in South Alabama in the 1890s. He robbed L&N freight trains and, according to lore, distributed goods to poor workers in the turpentine camps. Despite massive manhunts, he evaded capture for years. He was finally killed in 1896, ambushed at a general store.

The supernatural dimension of Railroad Bill emerged from the puzzle of his evasion. How could one man escape so many pursuits? Folklore provided the answer: he was a conjure man, possessed of supernatural powers that allowed him to shape-shift into a fox, a dog, or a sheep. Even after death, legends persisted that his ghost continued to ride the rails.

The psychology of Railroad Bill is the psychology of resistance mythology. He represents agency in a system designed to deny it. The shape-shifting power is a metaphor for the elusiveness of resistance itself, the way that oppression can never fully contain the human drive for freedom. His death did not end the legend because the need for such figures does not end with any individual’s death. Railroad Bill becomes an archetype, the unkillable spirit of rebellion against the Jim Crow order.

Granny Dollar and the Witch of Lookout Mountain

Nancy “Granny” Dollar, who died in 1931 at the age of 101, was the daughter of a Cherokee man who evaded the Trail of Tears. She lived on Lookout Mountain near Mentone, serving the community as midwife, herbalist, and fortune teller. She was known for her eccentric habits: a corn-cob pipe, a companion dog, a reclusive lifestyle.

The haunting of Granny Dollar is connected to a specific injustice. Near the end of her life, someone stole her life savings of $23, which she had hoarded to purchase a tombstone. She died with no marker for her grave. Her ghost is said to walk the mountain paths, accompanied by her spectral dog, searching for the recognition she was denied.

The psychology of Granny Dollar is the psychology of the marginalized healer. She represents the Indigenous and folk knowledge traditions that were displaced by professionalized medicine, the “old ways” that persisted in the hollows and mountains even as modernity advanced. Her ghost’s search for a tombstone is a search for acknowledgment, for the community to recognize the value of what she provided.

Hugging Molly and the Enforcement of Boundaries

In Abbeville, the legend of “Hugging Molly” serves a unique function: child discipline. Molly is described as a phantom woman, seven feet tall, dressed in black robes, who patrols the streets at night. When she finds children out past curfew, she does not kill them but chases them down, wraps them in a crushing hug, and screams into their ears.

This is the “bogeyman” archetype, the frightening figure used by parents to enforce rules. What distinguishes Hugging Molly is her non-lethality. She is terrifying but not ultimately dangerous. The consequence of encountering her is fear and humiliation, not death. This calibration makes her an effective disciplinary tool: the threat is real enough to motivate compliance but not so extreme as to be unbelievable.

The town of Abbeville has embraced Hugging Molly as a cultural icon (there is a restaurant bearing her name). This domestication of the bogeyman represents a community’s ability to incorporate its fears into its identity, to transform the source of childhood terror into a point of civic pride.

The Therapeutic Implications of Spectral Geography

Haunting as Symptom

Throughout this survey of Alabama’s supernatural landscape, a consistent pattern emerges: haunting as symptom. The ghosts do not appear randomly but cluster at sites of unprocessed trauma, unfulfilled obligation, and unacknowledged guilt. They are the symptoms of a collective psyche that has not completed its mourning, has not integrated its losses, has not reckoned with its crimes.

This is not unique to Alabama, but Alabama’s particular history, the layering of Indigenous displacement, plantation slavery, Civil War destruction, Reconstruction violence, industrial exploitation, and ongoing racial injustice, provides an unusually dense concentration of unmetabolized trauma. The state is, in psychological terms, complexly wounded, and the ghosts are the symptoms of those wounds.

The Function of Ghost Stories

Ghost stories serve several psychological functions that explain their persistence despite (or perhaps because of) their implausibility.

They provide frameworks for understanding loss. Death is incomprehensible, the absolute cessation of a presence that was woven into the fabric of daily life. Ghost stories offer the comfort that the dead are not entirely gone, that they persist in some form, that the relationship continues.

They externalize guilt. The Face in the Window does not require the descendants of lynch mobs to consciously acknowledge their heritage. The face does the acknowledging for them, externalizing the guilt onto the physical environment where it can be seen, discussed, and even denied without requiring direct engagement with historical responsibility.

They preserve what official history erases. The Nunnehi legends keep alive the Cherokee refusal to fully leave Alabama, even though the Trail of Tears physically removed the population. The Railroad Bill legends preserve the memory of Black resistance to Jim Crow, even though official histories of the period minimized or ignored such resistance. Ghost stories are a form of counter-memory, preserving what the dominant narrative would prefer to forget.

They provide entertainment and community bonding. The sharing of ghost stories is a social activity, a way of transmitting local knowledge and creating shared experience. The stories connect generations, creating continuity between those who first told the tale and those who hear it today.

When Haunting Becomes Pathological

In individual psychology, the persistence of the dead in consciousness can be adaptive or maladaptive depending on its intensity, duration, and impact on functioning. The widow who feels her husband’s presence in the early months of grief is experiencing a normal part of the bereavement process. The widow who refuses to change anything in the house, who sets a place at the table for her husband years later, who cannot move forward because she is perpetually waiting for his return, has entered complicated grief.

The same distinction applies to collective haunting. A community that preserves ghost stories as part of its cultural heritage, that tells the tales at Halloween, that incorporates them into tourist attractions, is engaging in adaptive cultural processing. A community that cannot discuss its history except through the displacement of ghost stories, that maintains the Face in the Window but cannot teach the history of lynching in its schools, is engaging in collective avoidance.

The question for Alabama, and for the South more broadly, is whether its abundant haunting represents cultural vitality or cultural pathology. The answer, I suspect, is both, in different proportions at different sites.

Toward Integration

In individual therapy, the goal with unresolved grief and persistent haunting is integration: bringing the lost object into a relationship with the present self that allows for both memory and movement. The dead are not forgotten but neither do they dominate. Their presence becomes a part of the self rather than an intrusion upon it.

What would integration look like for a haunted landscape? It would involve acknowledging the historical realities that generate the ghosts without becoming paralyzed by guilt. It would mean telling the full story, Indigenous displacement and plantation slavery and industrial exploitation and racial terror, without using ghost stories as a substitute for historical reckoning. It would require understanding that the ghosts will not leave until the work they represent is completed.

The Face in the Window at the Pickens County Courthouse will persist, the legend implies, until the community fully reckons with its history of racial violence. The ghost of Evelyn Carter will play her piano until she is somehow “returned” to Virginia, whatever that might mean in a world where she has been dead for 150 years. Slag Wormwood will push workers from the catwalks until the exploitation he represents is acknowledged and repudiated.

These are symbolic demands, not literal ones. They cannot be satisfied by physical actions (scrubbing the window, exhuming the corpse, performing an exorcism at the furnace). They can only be satisfied by the psychological work of integration, of facing what has been avoided, of completing what has been left unfinished.

Living Among Ghosts

I began this article by noting that Alabama is haunted. I want to end by suggesting that this haunting, properly understood, is not a curse but an invitation.

The ghosts of Alabama are not arbitrary. They cluster at the places where trauma occurred and was not processed, where guilt accumulated and was not acknowledged, where bonds were broken and not repaired. They are, in effect, markers on a map of the work that remains to be done. A landscape without ghosts would be a landscape that had fully metabolized its past, and no landscape has done that, certainly not this one.

To live among ghosts is to be reminded, constantly, that the past is not past. This can be paralyzing if we treat the reminder as condemnation. But it can be energizing if we treat it as invitation, a call to complete the work of mourning, to tell the full story, to build relationships with the dead that honor them without being imprisoned by them.

The Indigenous peoples of Alabama understood that the cosmos is larger than human comprehension, that powerful beings inhabit the waters and the mountains, that the boundary between the living and the dead is permeable. This is not primitive superstition but sophisticated psychology. We are not the masters of a dead world but participants in a living one, surrounded by presences that exceed our control.

The next time you drive through Alabama at dusk, passing the antebellum mansions and the industrial ruins and the creek bridges where babies cry, consider that you are passing through a landscape dense with memory. The ghosts are not asking to be feared. They are asking to be heard, to be acknowledged, to be integrated into a story that includes them without being dominated by them.

That is the work. It is not finished. It may never be finished. But the ghosts will wait. They have nothing but time.

0 Comments