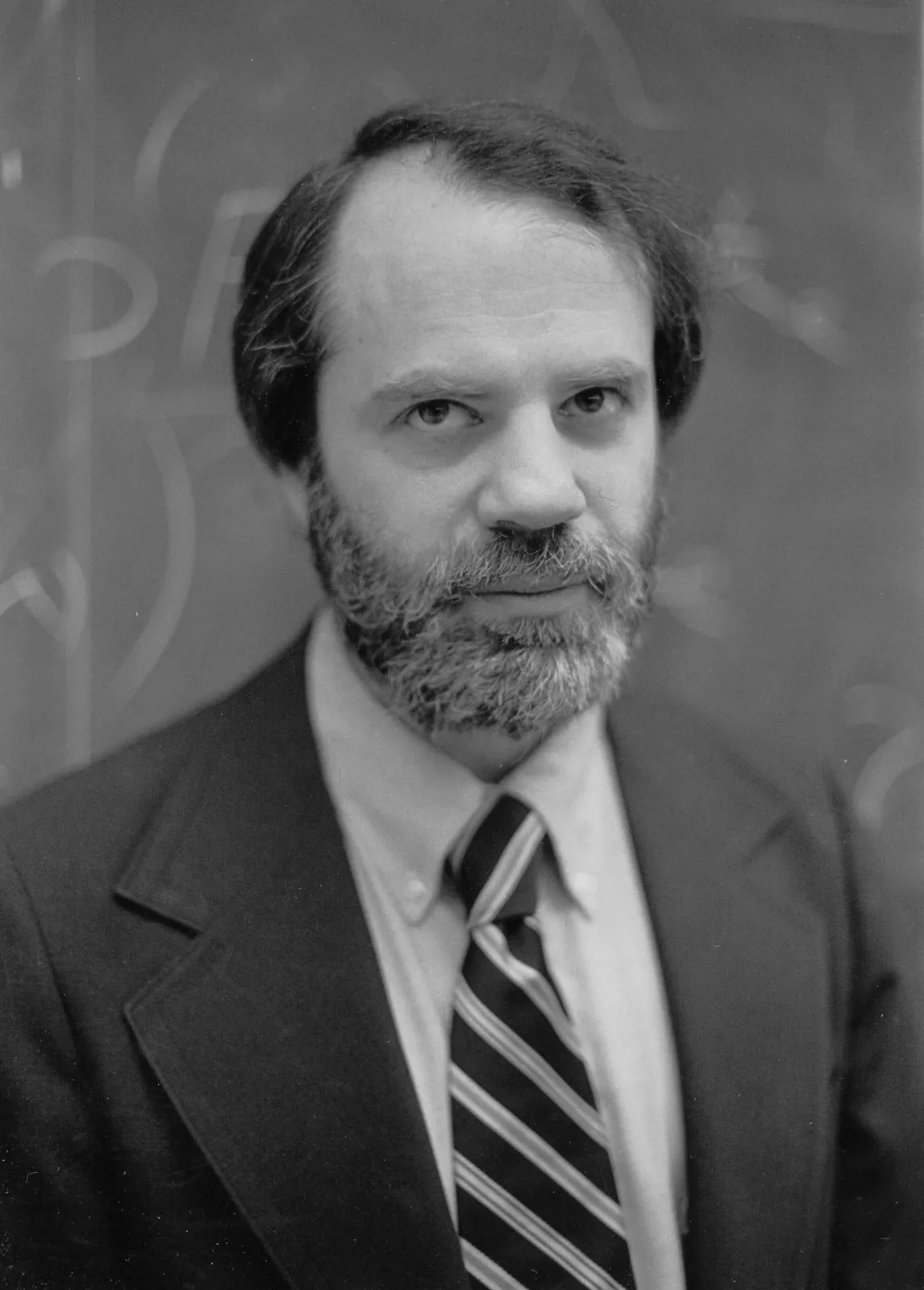

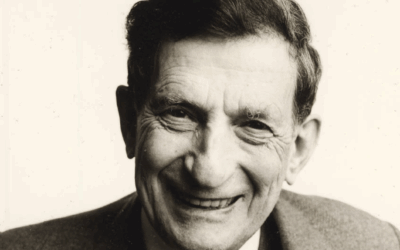

Who was Saul Kripke

Saul Kripke, a philosopher whose influence has reverberated through the intellectual landscape of the 20th century, is a name often associated with groundbreaking work in the philosophy of language, logic, and metaphysics. His ideas, though rooted in the technical intricacies of modal logic and semantics, have a profound reach that extends far beyond the confines of academic philosophy. In this extensive blog post, we will embark on an exploration of how some of Kripke’s pivotal concepts, such as rigid designation, the distinction between necessary and contingent truths, and the notion of rule-following, can illuminate central issues in psychotherapy and provide a framework for understanding the journey of psychological healing.

Rigid Designation and the Essence of Identity:

A cornerstone of Kripke’s philosophical contributions is the concept of “rigid designation” – the idea that certain terms, particularly proper names, refer to the same individual across all possible worlds or scenarios in which that individual exists. This stands in contrast to descriptive names, where the referent can vary depending on who happens to uniquely fit the description at a given time.

The notion of rigid designation has profound implications for how we conceptualize personal identity and the nature of the self. In the realm of psychotherapy, individuals often grapple with distorted beliefs about themselves, rooted in the internalization of negative messages or descriptions imposed by others. It could be argued that this struggle involves a fundamental confusion between rigid and non-rigid designation. An individual’s true self is a rigid designator – it refers to their unique essence as a person, irrespective of the shifting descriptions or roles they might contingently embody.

When an individual internalizes a negative self-image based on a description (e.g., “I am a failure,” “I am unlovable”), they are, in a sense, mistakenly elevating these contingent descriptions to the status of defining their core identity. However, who they are at their core remains unchanging, even as the descriptions applied to them fluctuate. Drawing on Kripke’s insights, we can see that the therapeutic process involves disentangling one’s fundamental sense of self from the accidental descriptions that have been attached to it.

Helping clients in psychotherapy to separate their essential identity from the contingent descriptions that have been imposed upon them is a crucial aspect of the healing journey. It opens the door to embracing one’s authentic self, even in the face of negative messages from the past. Kripke’s framework provides a robust philosophical foundation for this therapeutic task – recognizing that we are more than the sum of the shifting descriptions applied to us, and that our true selves remain constant beneath the surface of these contingent labels.

The Power of Contingency:

Rethinking Emotional Necessity Another fundamental theme that permeates Kripke’s work is the distinction between necessary and contingent truths. Necessary truths are those that could not have been otherwise – they are fixed and unchanging, like the truths of mathematics. Contingent truths, on the other hand, are those that just happen to be the case but could have been different under other circumstances.

This distinction finds a powerful echo in the realm of psychotherapy, particularly when it comes to understanding emotional experiences. Often, our emotional responses to situations feel necessary – as if they are inextricably and unalterably tied to the triggering circumstance. In the grip of a strong emotion, it can feel as if there is no other way we could possibly feel in response to what has happened.

However, when we examine our emotional reactions through the lens of Kripke’s distinction, we begin to see that they are often more contingent than they appear. Our emotional experiences are profoundly shaped by our beliefs, interpretations, past experiences, and patterns of thought. What feels like an inevitable, necessary response is often the product of a complex interplay of contingent factors.

Recognizing the contingent nature of our emotional ties to situations is a deeply empowering realization. It opens up a space for change and growth, revealing that we are not doomed to remain locked in negative emotional patterns, even if they feel inescapable in the moment. By exploring the contingent factors that shape our emotional responses, we can begin to develop a greater sense of flexibility and resilience in the face of life’s challenges.

Kripke’s framework provides a powerful conceptual tool for the therapeutic process, allowing us to reframe the task of therapy as an exploration of the contingent rather than necessary connections between circumstances and our inner emotional worlds. By recognizing that our emotional responses are shaped by a complex web of contingent factors, we open the door to the possibility of change and healing.

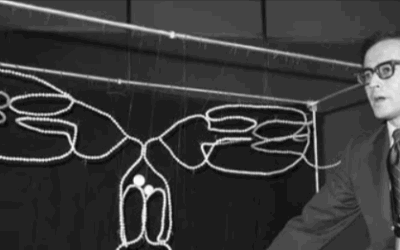

Rule-Following and the Social Construction of Meaning

Finally, Kripke’s penetrating analysis of Wittgenstein’s famous “rule-following” considerations has deep implications for the practice of psychotherapy. Kripke argues that no amount of facts about a person’s prior behavior or mental states can definitively determine how they ought to follow a rule going forward. There is always the possibility of interpreting the rule differently, of finding a new way to apply it that is consistent with one’s past actions.

The upshot of this analysis is that the meaning of rules, and of concepts more broadly, is irreducibly social. The way we interpret and apply the rules that govern our lives is not fixed by our individual pasts, but is shaped by the shared practices and understandings of our communities.

In the context of therapy, this insight can be applied to the “rules” or patterns that govern dysfunctional behaviors, modes of thinking, or emotional responses. There is often a fatalistic assumption that these patterns are fixed and immutable, determined by the individual’s history and experiences. But drawing on Kripke’s analysis, we can see that there is always an inherent openness in how we interpret and apply the rules we have inherited from our pasts.

Moreover, the fundamentally social nature of rule-following and meaning-making suggests that we cannot establish new patterns entirely on our own. We are deeply dependent on our social environments and relationships to shape the rules and meanings that structure our lives. The therapeutic relationship, then, can be understood as a microcosm of this social process – a space in which new shared meanings and patterns can be collaboratively established.

In this sense, therapy is not just about an individual changing their own patterns, but about the co-creation of new ways of interpreting and applying the rules that have governed a person’s life. The therapist-client relationship provides a socially scaffolded context in which old patterns can be re-examined and new possibilities can be explored.

Kripke’s work thus provides a powerful philosophical framework for understanding the transformative potential of the therapeutic relationship. By recognizing the openness and social basis of meaning and rule-following, we can begin to see therapy as a collaborative process of generating new possibilities for living.

The fact that Saul Kripke is not often directly cited in the context of psychotherapy perhaps says more about the academic silos that separate philosophy from therapeutic practice than it does about the relevance of his ideas. Notions like rigid designation, the distinction between the necessary and the contingent, and the social basis of meaning have profound implications for how we approach the process of psychological healing and transformation.

Kripke’s ideas provide a rich set of conceptual tools for re-examining fixed identities, exploring the malleability of emotional responses, and harnessing the power of relationships to generate new patterns of meaning and action. His work demonstrates the enduring relevance of philosophical reflection to the examined life – not just in the abstract realm of theory, but in the concrete, transformative work of therapy.

As practitioners and theorists of psychotherapy, we would do well to engage more deeply with the philosophical tradition that Kripke represents. His ideas have the potential to enrich our understanding of the human condition and to expand our sense of what is possible in the therapeutic process.

At the same time, the practical insights and experiences of psychotherapy have much to offer philosophy. The transformative work of therapy provides a rich ground for exploring how abstract philosophical ideas play out in the concrete reality of human lives. By bringing philosophy and therapy into closer dialogue, we open up new possibilities for understanding and facilitating the process of psychological growth and change.

In the end, Kripke’s work reminds us that the project of understanding the human mind and transforming human lives is not the exclusive province of any single discipline. It is a shared endeavor that requires us to draw on the insights of multiple traditions – from the rigorous analysis of philosophy to the practical wisdom of therapeutic practice.

By engaging with Kripke’s ideas in the context of psychotherapy, we participate in this broader intellectual and practical project. We expand our conceptual horizons, deepen our understanding of the human condition, and enrich our capacity to facilitate meaningful change in the lives of those we serve.

Key Ideas:

Saul Kripke’s influence on philosophy of language, logic, and metaphysics

Rigid designation:

The concept that certain terms, especially proper names, refer to the same individual across all possible scenarios

Implications for personal identity and self-concept in psychotherapy

Necessary vs. contingent truths:

Application to understanding emotional experiences in therapy

Reframing emotional responses as contingent rather than necessary

Rule-following and social construction of meaning:

Kripke’s analysis of Wittgenstein’s rule-following considerations

The social nature of meaning and its implications for therapy

Application of Kripke’s ideas to psychotherapy:

Separating essential identity from contingent descriptions

Recognizing the contingent nature of emotional responses

Understanding therapy as a collaborative process of creating new meanings

The therapeutic relationship as a microcosm for social meaning-making

Potential for integrating philosophical concepts into psychotherapeutic practice

The value of interdisciplinary dialogue between philosophy and psychotherapy

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Philosophy

Speculative Bibliography and Further Reading:

- Kripke, S. (1980). Naming and Necessity. Harvard University Press.

- Kripke, S. (1982). Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language. Harvard University Press.

- Putnam, H. (1975). The meaning of ‘meaning’. Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 7, 131-193.

- Lewis, D. (1986). On the Plurality of Worlds. Blackwell.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. (G.E.M. Anscombe, Trans.). Basil Blackwell.

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books.

- Rogers, C. R. (1961). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin.

- Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. International Universities Press.

- Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s Search for Meaning. Beacon Press.

- Gergen, K. J. (2009). Relational Being: Beyond Self and Community. Oxford University Press.

- Cushman, P. (1995). Constructing the Self, Constructing America: A Cultural History of Psychotherapy. Da Capo Press.

- Orange, D. M. (2011). The Suffering Stranger: Hermeneutics for Everyday Clinical Practice. Routledge.

- Stolorow, R. D. (2011). World, Affectivity, Trauma: Heidegger and Post-Cartesian Psychoanalysis. Routledge.

- Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Harvard University Press.

- Sass, L. A. (1992). Madness and Modernism: Insanity in the Light of Modern Art, Literature, and Thought. Basic Books.

0 Comments