In the history of psychology, there are the “safe” names—Freud, Skinner, Piaget—whose theories form the bedrock of modern textbooks. Then, there are the outliers. These are the thinkers who ventured so far to the edge of the map that they fell off: James Frazer, Julian Jaynes, Terence McKenna, and Paul MacLean. Today, many of their specific scientific claims have been debunked. We know that the brain didn’t evolve in neat “triune” layers like an onion. We know that mushrooms didn’t literally double the size of the hominid brain overnight. Yet, despite their factual errors, these theorists act as persistent ghosts in the machine of modern thought.

Why do we keep returning to them? Because while they may have been wrong about the hardware (the biology), they were often startlingly right about the software (the subjective experience). They provided metaphors that describe the human condition better than any fMRI scan ever could. As we move into an era of integrative psychology, we can look back at these “useful mistakes” not with scorn, but with curiosity. They remind us that the map is not the territory, and sometimes, a flawed map is the only way to find a new world.

1. The Golden Bough: James Frazer and the Logic of Magic

In 1890, the Scottish anthropologist James Frazer published The Golden Bough, a massive comparative study of mythology and religion. Frazer argued that human thought evolved in three stages: Magic, Religion, and Science. He proposed that “sympathetic magic” (the idea that like produces like, e.g., a voodoo doll) was simply “bad science”—a logical error made by primitive minds.

The Mistake: Frazer was an armchair anthropologist who never visited the cultures he wrote about. He was wrong to view magic as merely “failed science.” Indigenous rituals were not failed attempts to control the weather; they were successful attempts to control social cohesion and psychological states. He missed the functional reality of the ritual itself.

The Insight: Despite his colonial bias, Frazer correctly identified the associative nature of the unconscious. The human mind does work on magic. When a client keeps their ex’s sweatshirt because “it feels like them,” they are practicing sympathetic magic. When we avoid walking under a ladder, we are in the realm of the magical. Frazer gave us a language to understand the mythological substructure that still governs our dreams and neuroses today. He showed us that the “primitive” mind is not history; it is the basement of the modern psyche.

2. The Triune Brain: Paul MacLean and the Lizard Within

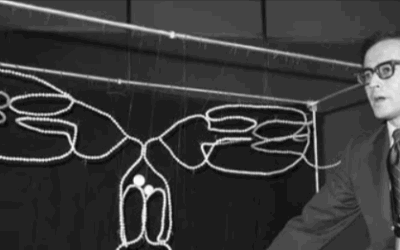

In the 1960s, neuroscientist Paul MacLean proposed the “Triune Brain” model. He suggested the brain had three distinct evolutionary layers: the Reptilian Complex (survival/aggression), the Paleomammalian Complex (emotion/limbic), and the Neomammalian Complex (rational thought). This idea permeated pop culture, giving us the concept of the “Lizard Brain.”

The Mistake: Modern neuroscience has thoroughly debunked this. Evolution doesn’t stack new brains on top of old ones like Lego bricks; it reorganizes the whole system. The “reptilian” basal ganglia are deeply integrated with the “rational” cortex. The brain functions as a network, not a layer cake.

The Insight: While anatomically wrong, the Triune Brain is a perfect phenomenological metaphor for trauma. When we are triggered, we feel like we have been hijacked by a lizard. We lose access to language (neocortex) and become pure instinct (reptile). This model remains useful in therapy not as a biology lesson, but as a way to help clients depathologize their reactions. It helps explain the “bottom-up” hijacking seen in amygdala responses, validating the felt sense of losing control.

3. The Bicameral Mind: Julian Jaynes and the Voices of God

Perhaps the most audacious theory of the 20th century came from Julian Jaynes. In The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (1976), he argued that ancient humans (until about 3,000 years ago) were not conscious in the modern sense. Instead, their brain hemispheres were split: the right hemisphere hallucinated commands (“voices of the gods”), and the left hemisphere obeyed them. He claimed that “consciousness” as we know it is a learned cultural software, not a biological inevitable.

The Mistake: There is zero archaeological or neurological evidence that the corpus callosum functioned differently in the Bronze Age. The timeline is impossible, and the idea that Homeric heroes were “zombies” is widely rejected.

The Insight: Jaynes correctly identified that the internal monologue is a recent development. He highlighted the fluid boundary between “me” and “not-me.” In conditions like schizophrenia or severe dissociation, this boundary dissolves, and internal thoughts are experienced as external voices. Jaynes forces us to ask: Is the “Self” a biological organ, or is it a story we learned to tell ourselves? This aligns with modern views on narrative identity and the fragile nature of the ego.

4. The Stoned Ape: Terence McKenna and the Origins of Language

Terence McKenna, the bard of psychedelics, proposed the “Stoned Ape Theory.” He argued that early hominids on the African savannah consumed psilocybin mushrooms growing in cattle dung. This psychedelic intake, he claimed, caused “synesthesia” (blurring of senses), which led to the development of spoken language. “Language,” he famously said, “is a synesthesia common to the tribe.”

The Mistake: Evolutionary biologists dismiss this as highly speculative. Language likely evolved slowly through social necessity, not a chemical jump-start. Furthermore, McKenna often drifted into pseudoscience regarding the “2012 apocalypse” and alien intelligence.

The Insight: McKenna was right about the power of altered states to dissolve rigid boundaries. He correctly intuited that language and consciousness are fundamentally psychedelic—they are virtual reality simulations we run in our heads. His insistence on the importance of “dissolving the ego” anticipates the current renaissance in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. He championed the idea that the mind is not a fixed object but a fluid process that can be expanded, a concept now validated by neuroplasticity.

5. The Integral Map: Ken Wilber and Stanislav Grof

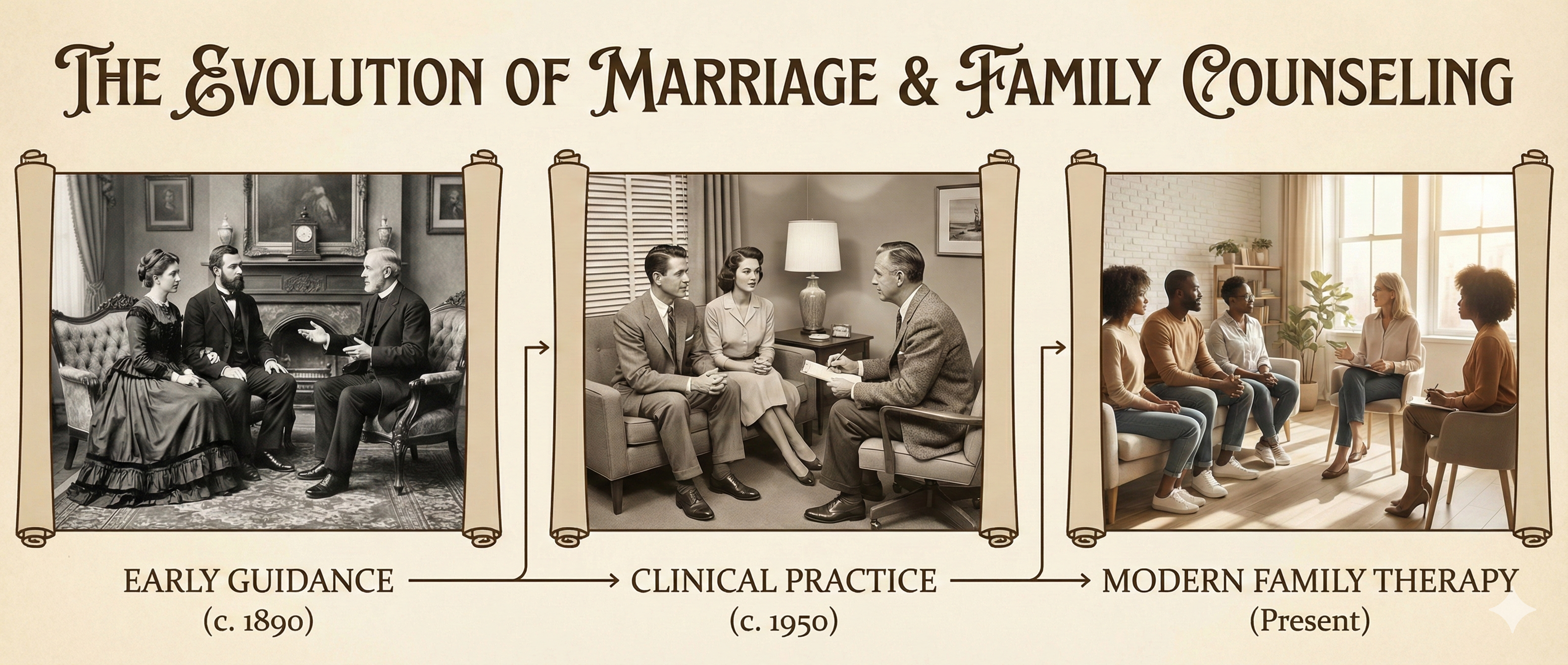

Finally, we have the grand synthesizers. Ken Wilber (drawing heavily on the phenomenologist Jean Gebser) and Stanislav Grof attempted to map the entire spectrum of human consciousness. Wilber’s “Integral Theory” argues that human development moves through stages: Archaic, Magic, Mythic, Rational, and Transpersonal. Grof, working with LSD breathwork, mapped the “Perinatal Matrices”—the psychological imprints of birth itself.

The Critique: These theories can become rigid “theories of everything,” risking cult-like dogmatism. They can over-categorize the messy reality of human life into neat color-coded boxes (Spiral Dynamics). Critics argue they sometimes force data to fit the model.

The Insight: They provide a meta-framework. They allow us to see that Freud wasn’t wrong, he was just focused on the “lower” basement levels. Jung wasn’t wrong, he was focused on the “upper” attic levels. Stanislav Grof’s work, in particular, validated the reality of “spiritual emergencies”—crises that look like psychosis but are actually attempts at healing. By mapping the full territory, they allow us to practice an integrative psychology that honors the body, the mind, and the spirit without having to choose just one.

The Value of Being Wrong

Science is not a straight line of truth; it is a zig-zag of correction. These fringe theorists may have failed as biologists or historians, but they succeeded as myth-makers. They gave us the vocabulary to talk about the parts of our experience that don’t fit in the lab. In therapy, we often use “wrong” metaphors—inner children, shadow figures, lizard brains—because they work. They help us make sense of the mystery of being human. Perhaps the lesson is that in the study of the soul, poetic truth is sometimes just as valuable as literal fact.

0 Comments