Every fall, thousands of freshmen arrive at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, ready to experience college life. Most will never hear the name Theta Nu Epsilon. But whether they know it or not, many of them will participate in a system controlled by this secret society, founded in 1888 and known colloquially as “The Machine.” For over a century, this organization has coordinated Greek life to dominate student government at Alabama, creating a pipeline of politically connected individuals who move directly into Alabama’s legal system, state politics, and the corporate boardrooms of Birmingham. The Machine is not folklore or conspiracy theory. It is documented history, and its influence on Alabama power structures represents one of the most enduring examples of institutional coordination in American political life.

The Origins and Structure of The Machine

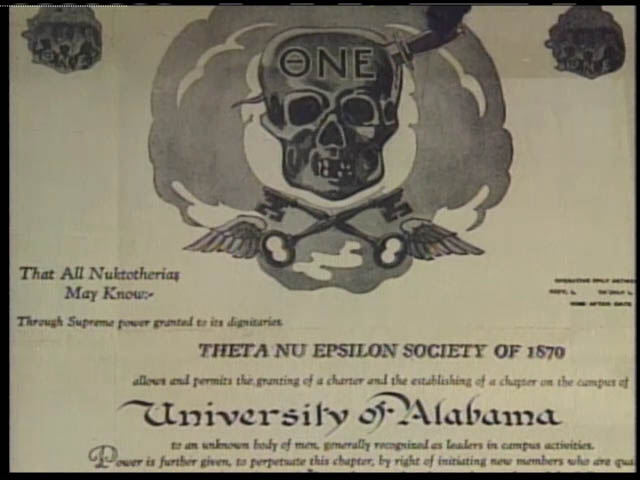

Theta Nu Epsilon was founded at Wesleyan University in Connecticut in 1870 as a secret society within the Greek system, eventually establishing chapters at universities across the South. The Alabama chapter, founded in 1888, became the most powerful and enduring iteration of the organization. Unlike traditional fraternities, The Machine operates as a coordinating body that sits above individual Greek organizations. Its membership draws from established fraternities and sororities, with traditionally white Greek organizations forming its core power base, though the organization has evolved and expanded over decades as the university’s Greek system has changed.

The Machine’s primary function is bloc voting. During University of Alabama student government elections, Machine-affiliated Greek organizations coordinate their members to vote as a unified bloc for Machine-selected candidates. Given that Greek life represents a substantial portion of the student body and that voter turnout in student elections typically hovers around 30 percent, this coordinated voting gives The Machine effective control over student government outcomes. The organization selects candidates for Student Government Association president, vice president, and numerous other positions months before elections occur. These candidates are groomed, funded, and supported through coordinated Greek system resources that independent candidates cannot match.

The process works with remarkable efficiency. Machine leadership, drawn from senior members of affiliated fraternities and sororities, meets privately to select preferred candidates. Once candidates are chosen, the word goes out through Greek channels. Chapter presidents inform members how to vote. Social pressure within tightly knit fraternity and sorority communities ensures compliance. On election day, Greek organizations coordinate transportation to polling places, monitor turnout, and deliver their members to vote in organized groups. The result is predictable: Machine candidates win with overwhelming consistency, creating a student government that serves as a training ground for future political operatives while maintaining an illusion of democratic process.

The Pipeline to Birmingham Power

The significance of The Machine extends far beyond campus politics. University of Alabama graduates, particularly those who participated in Machine-coordinated student government, move directly into positions of influence throughout the state. Birmingham’s major law firms, including those occupying the glass towers downtown, recruit heavily from Alabama Law School, with preference often given to candidates who held student government positions. These same individuals eventually become judges, city council members, state legislators, and corporate executives. The networking that begins in Tuscaloosa fraternities extends seamlessly into Birmingham’s legal and political establishment.

Walk through the law offices lining 20th Street North in downtown Birmingham, and you will find conference room walls decorated with University of Alabama degrees and photographs of partners who served in student government positions during their college years. Many of these individuals belonged to the same fraternities that coordinate through The Machine. They attend the same alumni events, belong to the same social clubs, live in the same neighborhoods in Mountain Brook and Vestavia Hills, and hire each other’s children for internships and entry-level positions. The Machine does not need to continue operating as a formal organization beyond the university because its members have internalized the coordination model. The network becomes self-perpetuating.

Jefferson County politics has been particularly influenced by this pipeline. Multiple county commissioners, Birmingham city council members, and mayors have emerged from the University of Alabama Greek system with direct or indirect Machine connections. State legislative positions representing Birmingham’s wealthiest suburbs often go to candidates with the right fraternity credentials and the networking advantages those credentials provide. Even when The Machine itself is not actively coordinating these outcomes, the habit of insider coordination, the preference for connected candidates, and the mutual support among Greek alumni create similar results.

How The Machine Maintains Secrecy and Deniability

Despite being one of the worst-kept secrets in Alabama, The Machine maintains remarkable operational security through a combination of factors. First, the organization technically does not exist as a legal entity. There are no official membership rolls, no tax documents, no registered officers. Theta Nu Epsilon chapters at other universities have largely faded into historical obscurity, but at Alabama, the name persists in cultural memory while the actual organizational structure remains deliberately vague.

Second, discussing The Machine openly is discouraged within Greek life through social pressure and the implicit understanding that acknowledging coordination undermines its effectiveness. Students learn quickly that asking too many questions about how decisions get made or who selected particular candidates marks them as outsiders. Greek members who benefit from Machine coordination have strong incentives to maintain ambiguity about how the system operates. Those who oppose it often lack the evidence or organizational leverage to effectively challenge it.

Third, the university administration maintains careful distance from the topic. Officials acknowledge that Greek organizations coordinate politically, but they avoid confirming The Machine’s existence as a specific entity. This deniability serves institutional interests by allowing the university to claim that student government operates democratically while avoiding responsibility for addressing the coordinated manipulation that undermines that democracy. When journalists investigate or student activists complain, the response is typically that Greek students simply vote in higher numbers and organize more effectively than independents, as though coordination at The Machine’s level were equivalent to normal political organizing.

The Anti-Machine Movement and Why It Always Fails

Periodically, reform movements emerge at Alabama to challenge Machine dominance. Independent candidates run for student government promising to represent all students rather than Greek interests. Student journalists expose the coordination and call for transparency. Faculty members express concern about the implications of training future political leaders in a system built on insider manipulation. These movements generate brief attention, sometimes even winning isolated victories, but The Machine’s structural advantages prove overwhelming.

Independent candidates lack the organized turnout mechanism that Greek coordination provides. They cannot match the funding that flows through established Greek networks. Most critically, they cannot overcome the social consequences of opposing The Machine within a campus culture where Greek affiliation often determines social status, networking opportunities, and post-graduation career prospects. Students who actively campaign against Machine candidates often find themselves socially isolated, and those with ambitions in Alabama law or politics learn that making enemies of the Greek establishment in college can have professional consequences years later.

The Machine also adapts. When accused of being exclusively white, the organization began including historically Black Greek organizations in its coordination, though questions persist about how power and decision-making authority are distributed within the expanded coalition. When criticized for being antidemocratic, Machine candidates learn to use the rhetoric of inclusion and representation while continuing to operate through the same coordinated mechanisms. The sophistication with which The Machine absorbs criticism and adjusts its public presentation without changing its fundamental operation demonstrates precisely the kind of political skill that makes its alumni successful in Alabama’s broader political landscape.

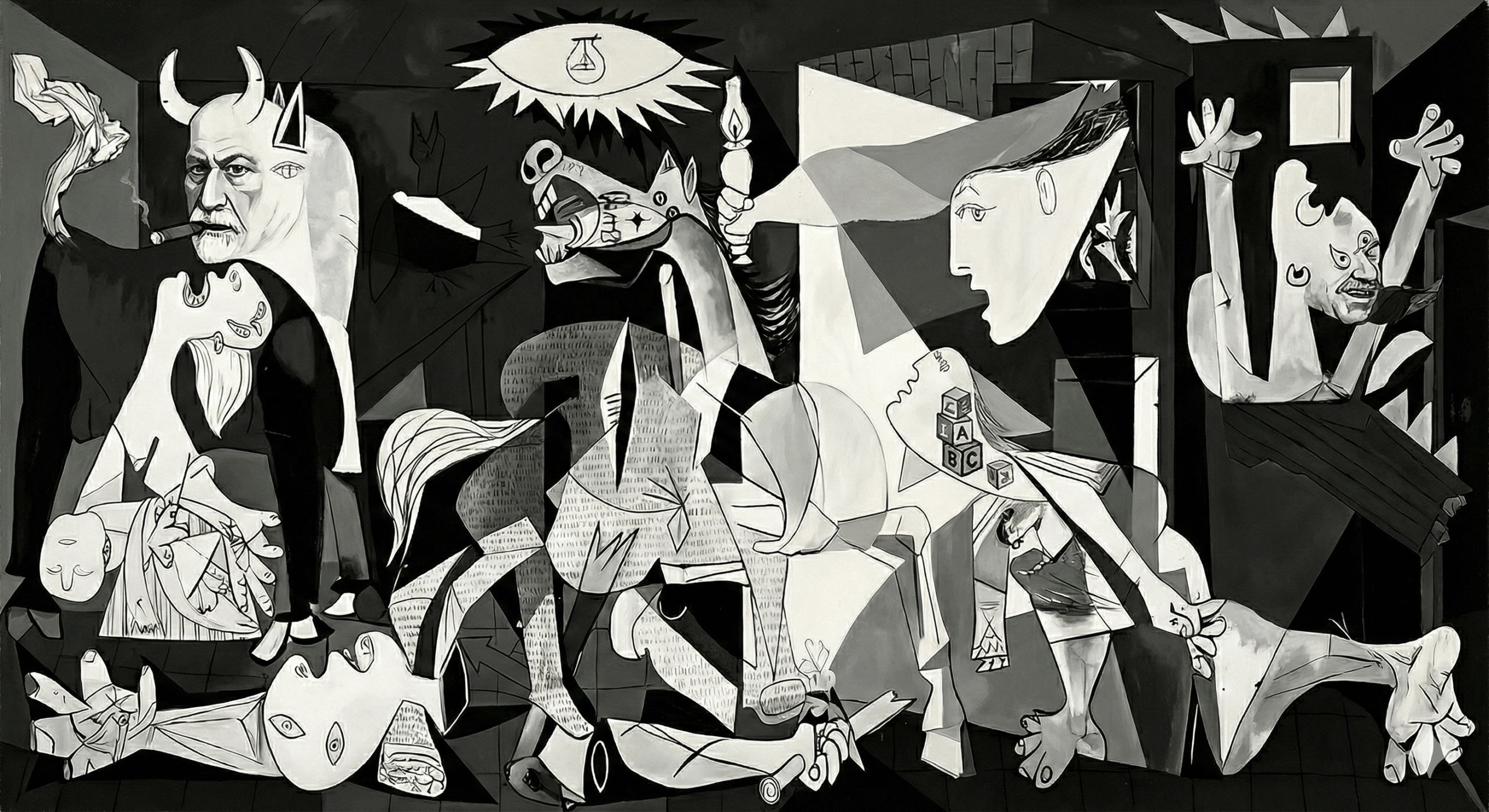

The Era of Violence: When The Machine Showed Its True Face

The Machine’s history is not merely one of coordinated voting and social pressure. Between 1976 and 1993, the organization’s resistance to change manifested in acts of violence and racial terror that reveal the stakes its members believed they were defending. These incidents demonstrate that for many within the Machine’s core, maintaining power was worth crossing into criminality.

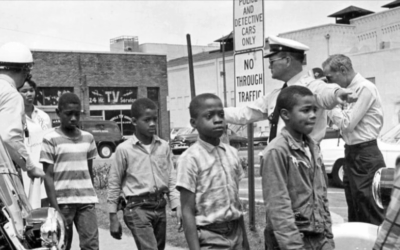

In 1976, Cleo Thomas became the first Black student elected SGA President, defeating the Machine candidate in an upset that sent shockwaves through the Old Row establishment. The response was immediate and visceral. Following Thomas’s victory, fifteen men dressed in white sheets burned a cross on campus while throwing bottles and chanting what witnesses described as “revolutionary tunes.” The Klan imagery was deliberate. For the Machine’s most extreme elements, the loss of political control represented an existential threat to the racial order they believed the organization existed to protect.

A decade later, John Merrill ran an anti-Machine campaign that subjected him and his supporters to a coordinated campaign of terror. Merrill personally discovered two alleged Machine members burglarizing his campaign office. A member of his campaign staff was run off the road while driving home. Most disturbingly, Merrill reported that his wife received telephone calls threatening her with rape if he did not withdraw from the race. Simultaneously, a cross was burned on the lawn of a house that Alpha Kappa Alpha, a historically Black sorority, was preparing to occupy. While no one was criminally charged for these incidents, the timing and context pointed unmistakably toward Machine elements enforcing both political and racial boundaries.

The violence reached its zenith in 1993 when Motes, a female independent candidate for SGA President, became the target of escalating intimidation. Initially, a cross was burned in her yard and threatening notes appeared in her mailbox. When she refused to withdraw from the race, an assailant attacked her at her home, leaving her with a golf-ball-sized bruise on her cheek, a busted lip, and a knife wound to the side of her face. The brutality of an assault on a female student finally forced the University administration to act. The University suspended the Student Government Association for three years, from 1993 to 1996, acknowledging that the student government had become a vehicle for criminal conspiracy.

These incidents were not aberrations. They represent what happens when an organization built on maintaining insider privilege faces genuine threats to its monopoly on power. For residents of Birmingham who wonder why the Machine matters beyond campus politics, these episodes provide the answer: the same individuals who learned that violence and intimidation were acceptable tools for maintaining power in Tuscaloosa went on to become Alabama’s lawyers, judges, and political leaders.

The Mechanics of Silence: How The Machine Enforces Loyalty

The Machine’s power rests not primarily on violence but on a sophisticated system of social coercion that makes resistance psychologically unbearable for most participants. At the operational level, the organization enforces compliance through what insiders call “the fine system” and “social embargoes.”

The bloc vote mechanism works with industrial efficiency. In the pre-digital era, pledges were physically transported in vans to polling stations, handed pre-marked slate cards listing Machine-approved candidates, and supervised while casting their ballots. With electronic voting, the tactics evolved. Reports from the 2000s and 2010s document fraternity members being required to vote in computer labs supervised by Machine representatives. In some cases, members were instructed to surrender their myBama login credentials, allowing representatives to cast votes directly on their behalf.

To ensure compliance, member houses enforce a system of fines disguised as “social assessments” or “parlor fees.” Members who fail to vote or who are suspected of voting independent can be fined hundreds of dollars. More devastating than financial penalties, however, are the social embargoes. Houses that defy Machine directives are barred from “swaps”—the mixers with top-tier sororities that are essential for recruitment. In the hyper-competitive market of Greek recruitment at Alabama, being cut off from Old Row social events can destroy a fraternity’s ability to attract new members, effectively killing the chapter.

The psychological toll of this system appears most clearly in the 1983 case of Alecia Sherard Archibald. Sherard was a member of Phi Mu and a writer for The Crimson White, the student newspaper that had long investigated Machine activities. She was summoned by her alumni advisor and given an ultimatum: quit her job at the newspaper and break up with her “GDI” (God Damn Independent) boyfriend, or surrender her sorority pin. The Machine viewed her association with independents and the press as a security risk. She chose to leave the sorority, later describing the experience as “gathering the pink confetti of my dignity.”

Sherard’s story illustrates why the Machine has survived for over a century despite periodic scandals and reform efforts. The organization is not merely a political party. It is the gatekeeper to the entire social world that defines four years of life for thousands of students. To defy the Machine is to face exile from that world during the developmental period when social belonging matters most. This enforcement mechanism ensures that most students comply silently, participate in the system they privately question, and carry the psychological residue of that compromise into their adult lives.

From the Basement to the Boardroom: The Birmingham Connection

The Machine functions as the most effective political training program in American higher education, and its graduates dominate Alabama’s legal and political establishment. The skills honed in fraternity basements—bloc voting, coalition management, enforcing silence, and neutralizing opposition—translate directly into success in Alabama politics and Birmingham’s corporate world.

The roster of Machine alumni reads like a directory of Alabama power. Senator Lister Hill, the organization’s founder, served in the U.S. Senate from 1938 to 1969 and became a master of parliamentary procedure. Senator John Sparkman became Adlai Stevenson’s running mate in 1952 and chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Senator Richard Shelby, one of the most powerful appropriators in Senate history, began his career in the Machine-controlled SGA of the 1950s. Governor Don Siegelman, the last Democrat to serve as Alabama’s governor, emerged from the same system. Bill Baxley, who as Attorney General prosecuted the KKK bombers of the 16th Street Baptist Church, nevertheless came up through the Machine structure.

This pipeline extends directly into Birmingham’s legal community. The major downtown firms function partly as extensions of the University of Alabama Greek system. Summer associate positions flow disproportionately to Alabama Law students with the right fraternity connections. Partnership tracks favor attorneys who can generate business through established networks, and those networks derive largely from Greek affiliations formed decades earlier. The pattern extends beyond law into banking, real estate development, and corporate leadership throughout Birmingham’s business community.

The Machine creates lifelong bonds between Alabama’s future power brokers. A deal negotiated in a fraternity basement in 1985 provides the foundation for a legislative alliance in 2010. A sorority sister from 1995 becomes the connection that secures a lucrative contract in 2020. For Birmingham residents in Homewood, Vestavia Hills, and Mountain Brook who navigate these professional networks, the Machine’s influence is not historical curiosity but present reality. The attorney handling your real estate closing, the judge presiding over your case, the city councilman representing your district, the executive reviewing your resume—all may share connections forged through Machine participation decades ago.

Pulitzer Prize winner John Archibald, himself a Machine alumnus, acknowledged this reality directly: “Everything for good or ill—I owe to ‘The Machine’… If not for Theta Nu Epsilon… I would be somebody else entirely.” This is not merely about political philosophy or policy positions. The Machine socializes young people into a specific style of governance that values elite consensus, secrecy, and the ruthless suppression of opposition. These values, learned at nineteen in a fraternity basement, shape how Alabama’s leaders govern at fifty from legislative chambers and corporate boardrooms.

The Fight for Integration and the Limits of Reform

For most of its history, the Machine operated as an explicitly white institution that actively enforced segregation within the Greek system. While the University of Alabama integrated in 1963, the Old Row fraternities and sororities remained segregated well into the 21st century, with the Machine playing a critical role in maintaining racial boundaries.

The Melody Twilley case in 2000-2001 exposed the mechanism of this enforcement. Twilley was a Black student with a 3.87 GPA who attempted to rush the historically white sororities. Despite strong support from alumni and some chapter members, she was rejected by all fifteen white sororities for two consecutive years. Reports surfaced that the Machine had threatened chapters with social ostracism if they offered her a bid. The logic was coldly tactical: if one house integrated, the Machine’s unified white bloc identity would fracture, potentially allowing independent or multicultural coalitions to challenge Old Row dominance.

The dam finally broke in 2013 following an exposé in The Crimson White detailing how alumnae and Machine advisors had blocked the recruitment of two Black women. The story went viral, attracting coverage from Time and The New York Times. Faced with a public relations disaster, University President intervened, forcing sororities to institute continuous open bidding to admit Black members. This represented the first time external media pressure successfully overrode the Machine’s social control.

Two years later, in 2015, Elliot Spillers became the first Black student elected SGA President since Cleo Thomas’s 1976 victory. Spillers built a coalition of New Row fraternities that defected from Machine control, multicultural student organizations, and activists from the “We Are Done” protest movement. His victory demonstrated that the Machine’s mathematical dominance was no longer guaranteed. As the University grew to over 38,000 students with a majority coming from out-of-state, Old Row could no longer simply outvote the rest of campus by default.

The Digital Age and the Return of Intimidation

The Machine’s tactics continued evolving into the 2020s, but recent events demonstrate that intimidation remains central to its operation. In October 2024, Maria Derisavi withdrew from the Homecoming Queen race days after being selected for the court. In a courageous op-ed for The Crimson White, she detailed a “relentless intimidation effort” designed to coerce her withdrawal. Derisavi described anonymous texts, phone calls, and meetings where she was pressured to step aside for the Machine-backed candidate. Her public accusation forced the University to confront reality: despite integration reforms and independent victories, the Machine’s coercive tactics persisted.

The University responded in early 2025 by amending the Code of Student Conduct to explicitly prohibit “intimidation and coercion of candidates in campus elections.” This represented the most significant administrative action against the Machine since the 1993 SGA suspension. By codifying intimidation as a conduct violation, the University created mechanism to expel students and potentially suspend chapters engaged in these tactics. Student leaders praised the move while noting it “does not address the core issue” unless the University is willing to “name the problem… the big bad M word.”

For Birmingham residents, particularly those in therapeutic practice, these recent events matter because they demonstrate continuity between historical violence and contemporary coercion. The students who participated in intimidating Maria Derisavi in 2024 will graduate and enter Birmingham’s professional world in 2025 and 2026. They will bring with them the lessons they learned about power, loyalty, and the consequences of opposition. The psychological patterns established through Machine participation do not end at graduation. They extend into marriages, parenting, professional relationships, and civic engagement throughout Birmingham and its suburbs.

From Tuscaloosa to Birmingham: How the Network Extends

For residents of Birmingham, Homewood, Vestavia Hills, and Mountain Brook, The Machine’s influence is not abstract or distant. It is the attorney who handles your real estate closing, the judge presiding over your civil case, the city councilman representing your district, the executive reviewing your resume at the firm where you hope to work. The coordination that begins in Tuscaloosa does not end at graduation. It extends into every elite institution in Alabama, creating a network where opportunity flows primarily through insider channels and where credentials from the right fraternity or sorority open doors that merit alone cannot.

This becomes particularly visible in Birmingham’s legal community. The major downtown firms function partly as extensions of the University of Alabama Greek system. Summer associate positions go disproportionately to Alabama Law students with the right connections. Partnership tracks favor those who can bring in business through established networks, and those networks derive largely from Greek affiliations. The same pattern appears in banking, real estate development, and corporate leadership throughout Birmingham’s business community. The Machine’s formal operations may be limited to campus, but its effects structure the entire professional ecosystem of Alabama’s largest city.

Even Birmingham residents who never attended Alabama and who have no direct connection to Greek life encounter The Machine’s influence through the institutions it has shaped. When you notice that city contracts seem to flow to the same connected firms, when you observe that political appointments favor candidates from similar backgrounds, when you recognize that certain families in Mountain Brook seem to have access to opportunities unavailable to equally qualified outsiders, you are observing the ripple effects of a coordination system that has been operating for over 130 years. The Machine is not the only network creating these patterns, but it is among the most powerful and enduring.

The most insidious form of gaslighting occurs when someone tells you that the rigging of the game is all in your head, except in Alabama, we know better. We know about The Machine. We have watched it operate for over a century at the University of Alabama, and we have seen its graduates filter into the law firms that line the glass towers of downtown Birmingham, into the political infrastructure of Jefferson County, and into the old money estates that dot the hills of Mountain Brook and Vestavia. The Machine is not a conspiracy theory. It is a documented secret society known formally as Theta Nu Epsilon, and its influence on Alabama politics represents something psychologically fascinating and clinically significant: a scenario in which institutional paranoia is not a symptom but a rational response to reality.

The Psychological Weight of Validated Suspicion

When clients come into therapy reporting that they feel like “the game is rigged” or that “there are invisible forces controlling outcomes,” we typically explore these beliefs through the lens of cognitive distortions, examining whether the person is catastrophizing or engaging in paranoid ideation. However, for those who grew up in Alabama, attended the University of Alabama, or work within the political and legal systems that govern Birmingham and its affluent suburbs, this belief may be empirically accurate. The Machine operates through a complex network of Greek organizations at the University of Alabama, coordinating votes in student government elections with ruthless efficiency and creating a pipeline of connected individuals who move seamlessly into positions of influence throughout the state.

The psychological impact of living within a system where hidden power structures are real cannot be overstated. Research on institutional betrayal, a term coined by psychologist Jennifer Freyd, demonstrates that when institutions meant to support and protect us instead operate through covert hierarchies that benefit insiders, the resulting trauma differs significantly from interpersonal betrayal. Institutional betrayal creates what psychotherapists call “complex relational trauma,” where trust becomes fundamentally destabilized not just in individual relationships but in the very fabric of social systems. For residents of Homewood watching city council decisions unfold, for attorneys in downtown Birmingham navigating the politics of large firms, or for families in Vestavia Hills engaging with school boards and municipal governance, the awareness that Machine-connected individuals may be coordinating behind the scenes introduces a layer of institutional paranoia that is both exhausting and rational.

Gaslighting at the Systemic Level

Traditional definitions of gaslighting focus on interpersonal manipulation where one person causes another to question their own perception of reality. However, when we examine The Machine’s influence on Alabama politics, we observe gaslighting operating at a systemic level. The organization’s existence is simultaneously acknowledged and dismissed. Everyone knows about it. Articles have been written. Former members have confirmed its operations. Yet when someone raises concerns about its influence on specific outcomes, they are often treated as paranoid or conspiratorial. This creates a uniquely destabilizing psychological environment where individuals learn they cannot trust their own accurate perceptions of reality because the culture around them treats those perceptions as delusional.

The therapeutic consequences of systemic gaslighting appear regularly in my practice at Taproot Therapy Collective in Hoover, where clients from across the Birmingham metro area describe experiences that follow a consistent pattern. They observe patterns of favoritism, coordinated decision making, or insider knowledge that seems impossible without some form of organized collaboration. They mention these observations to colleagues, friends, or family members, and they are told they are being paranoid or seeing patterns where none exist. Yet the patterns persist. The promotions go to the same network. The political appointments favor the same pipelines. The sense of being simultaneously right and crazy becomes unbearable.

Learned Helplessness and the Illusion of Meritocracy

One of the most damaging psychological consequences of The Machine’s influence is the development of learned helplessness, particularly among ambitious young professionals who move to Birmingham’s legal, financial, and political sectors without the right connections. Martin Seligman’s research on learned helplessness demonstrated that when organisms repeatedly encounter negative outcomes they cannot control, they eventually stop trying to change their circumstances, even when change becomes possible. The Machine creates precisely this dynamic for outsiders. You can work harder, be more qualified, demonstrate superior leadership, and still watch opportunities flow to those within the connected network. Over time, this creates a profound sense that effort does not matter, that merit is an illusion, and that the game is fundamentally unwinnable for those outside the invisible circle.

This dynamic plays out across Birmingham’s wealthiest suburbs with particular intensity. Mountain Brook, historically the epicenter of old money and established networks in Birmingham, operates within social structures where connections matter enormously. The same families attend the same churches, belong to the same country clubs, and send their children to the same schools. The Machine’s influence represents merely one layer of a much deeper pattern of insider networks that characterize the entire region. For those who move to Vestavia Hills or Homewood seeking upward mobility through professional achievement, the discovery that advancement often depends less on competence than on connection can be psychologically devastating.

The Paranoia That Keeps You Safe

Not all paranoia is pathological. Psychologists distinguish between persecutory delusions, where threats are imagined, and reasonable vigilance, where threats are real but the emotional response feels overwhelming. When The Machine is an actual force shaping outcomes in Alabama politics and Birmingham professional life, a certain level of institutional paranoia becomes adaptive. Clients who have learned to watch for patterns of insider coordination, who think carefully about which information they share with whom, and who feel anxious about navigating systems where invisible hierarchies determine outcomes are not displaying symptoms of mental illness. They are displaying appropriate situational awareness.

The challenge in therapy becomes helping clients distinguish between adaptive vigilance and the kind of hypervigilance that exhausts them and limits their capacity for trust in any context. Someone who worked in Alabama politics and learned that The Machine was coordinating against their initiatives has genuinely experienced institutional betrayal. Someone who extends that same level of suspicion to every organization, relationship, or social context may be overgeneralizing from past trauma. The therapeutic work involves helping clients develop what researchers call “discriminative trust,” the capacity to assess which situations genuinely warrant caution and which situations offer opportunities for authentic connection.

The Architecture of Invisible Power

Birmingham’s built environment mirrors the psychological dynamics of hidden power structures. The glass towers downtown create an architecture of surveillance and visibility, where everyone can see in but the actual mechanisms of decision making remain obscured behind boardroom doors and private clubs. The sprawling estates of Mountain Brook hide behind gates and long driveways, suggesting wealth and influence that operates beyond public view. Even the layout of Homewood and Vestavia Hills, with their winding roads and cul-de-sacs, creates a geography that discourages transparency and encourages insular networks. The physical architecture of Birmingham reinforces the psychological architecture of power that The Machine exemplifies: a system that everyone knows exists but that operates most effectively when its actual mechanisms remain obscured.

This architectural psychology matters because our physical environments shape our psychological experiences in profound ways. When you work in downtown Birmingham surrounded by the infrastructure of old money and political power, when you drive through Mountain Brook past estates that represent generations of accumulated advantage, or when you navigate the professional networks of Vestavia Hills where everyone seems to know everyone else except you, the built environment itself becomes a constant reminder of your outsider status. The Machine is not just a secret society at the University of Alabama. It is a symbol of all the invisible networks that structure opportunity and access in Alabama, and its psychological impact extends far beyond those who directly encounter it.

Treating Institutional Trauma in Birmingham

The therapeutic approach to institutional betrayal and systemic gaslighting requires validation before intervention. Clients who have experienced The Machine’s influence, whether directly in Alabama politics or indirectly through its ripple effects in Birmingham’s professional world, need their perceptions confirmed before they can begin to heal. Yes, the networks are real. Yes, the insider advantage exists. Yes, you were right to notice the patterns that others told you were imaginary. This validation provides the foundation for addressing the secondary trauma: the learned helplessness, the difficulty trusting new organizations, the hypervigilance that makes every professional interaction feel like navigating a minefield.

At Taproot Therapy Collective, we work with clients across the Birmingham metro area who are processing these dynamics through modalities specifically designed for complex relational trauma. Somatic experiencing helps clients recognize how institutional betrayal lives in the body, creating patterns of bracing and defensive tension that persist long after the threatening environment has changed. Brainspotting allows us to access the deep subcortical processing where institutional paranoia gets encoded, helping clients distinguish between past experiences that warrant caution and present situations that offer genuine safety. Lifespan integration helps clients recognize that their younger selves made accurate assessments of dangerous systems and that the wisdom they developed can now be applied more flexibly rather than becoming a rigid defensive stance applied to all contexts.

Reclaiming Agency in Rigged Systems

The most important therapeutic goal for clients dealing with institutional betrayal is not to convince them the world is fair when it demonstrably is not. The goal is to help them reclaim agency even within unfair systems. The Machine’s power depends partly on the learned helplessness it creates in outsiders. When people believe that effort does not matter because outcomes are predetermined, they stop trying to create change. When people become so focused on invisible networks that they cannot see actual opportunities for influence and impact, they inadvertently reinforce the very powerlessness they fear. The therapeutic work involves helping clients develop realistic assessments of which battles are winnable, which systems can be influenced from within, and which contexts require them to either accept the limitations or redirect their energy elsewhere.

For professionals in Birmingham, Homewood, Vestavia Hills, or Mountain Brook who are navigating systems influenced by The Machine or similar insider networks, this might mean developing coalitions with others who share their outsider status. It might mean choosing to compete in arenas where merit matters more and connections matter less. It might mean making peace with the reality that some opportunities will never be available and focusing energy on creating new opportunities that bypass existing power structures entirely. The point is not to become naive about how power operates in Alabama. The point is to refuse to let accurate perceptions of institutional corruption become an excuse for total resignation.

The Conspiracy That Teaches Us to Trust Ourselves

Paradoxically, The Machine’s existence offers an important gift to those aware enough to receive it. In a culture that often pathologizes suspicion and treats skepticism of authority as a symptom requiring treatment, The Machine provides irrefutable evidence that sometimes the conspiracy is real, that sometimes the game is actually rigged, and that sometimes your perception that invisible forces are coordinating against you is simply accurate. This validation can help clients trust their own instincts in other contexts. If you were right about The Machine when everyone told you that you were paranoid, perhaps you can trust your gut when something feels off in your workplace, your family system, or your intimate relationships.

The therapeutic challenge is helping clients use this validation wisely. Knowing that some institutions betray trust does not mean all institutions are corrupt. Knowing that The Machine exists does not mean every closed door represents a conspiracy. The work of therapy involves helping clients develop the psychological flexibility to hold apparently contradictory truths simultaneously: that institutional betrayal is real, and that trust is still possible; that invisible networks shape outcomes in Alabama politics and Birmingham professional life, and that individual agency still matters; that the game is sometimes rigged, and that playing anyway can still be worthwhile.

If you are struggling with institutional betrayal, gaslighting in professional contexts, or the learned helplessness that comes from navigating systems where insider advantage seems insurmountable, therapy can help you process these experiences without losing your capacity for discernment or your will to keep engaging with the world. At Taproot Therapy Collective in Hoover, we specialize in treating complex relational trauma, including the unique psychological impact of living and working in communities where invisible power structures are not paranoid fantasies but documented realities. The Machine teaches us that sometimes the conspiracy is real. Therapy teaches us that even in rigged systems, we can find ways to reclaim our agency, trust our perceptions, and build lives worth living. For residents of Birmingham and surrounding communities who are ready to address these dynamics, reaching out for support is the first step toward transforming institutional trauma into hard-won wisdom that serves rather than imprisons you.

0 Comments