The Grand Unifier: Theodore Millon and the Mathematical Architecture of the Self

In the fragmented landscape of 20th-century psychology, where clinicians pledged loyalty to competing schools of thought like feudal lords, Theodore Millon (1928–2014) stood as a rare figure of integration. While Sigmund Freud mapped the depths of the unconscious and B.F. Skinner charted the mechanics of behavior, Millon sought to build a bridge between them using the laws of evolution and the rigor of mathematics.

Millon was not merely a psychologist; he was a personologist. He coined this term to describe the study of the whole person—not just their symptoms, but the structural, enduring patterns of being that define who they are. He argued that a diagnosis without a theory is “blind,” a mere checklist of complaints. His life’s work was to provide vision to psychiatry, grounding the study of personality disorders in the bedrock of evolutionary biology. He believed that every personality style, no matter how pathological it appears, began as an evolutionary survival strategy.

I. Biography: The Making of a Polymath

Early Life and the Intersection of Disciplines

Born on August 18, 1928, in New York City, Theodore Millon was the only child of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants. His upbringing was steeped in the immigrant drive for intellectual achievement. He initially did not intend to study psychology; his first loves were physics and philosophy. This background is crucial to understanding his later work. Unlike clinicians who rely on intuition, Millon approached the human mind with the eye of a physicist looking for universal laws.

He received his Ph.D. from the University of Connecticut in 1954, but his intellectual appetite could not be sated by the behaviorism that dominated American universities at the time. He found behaviorism too sterile—it ignored the internal world. Yet, he found psychoanalysis too vague—it lacked empirical rigor. Millon spent the 1960s as a professor at Lehigh University, where he began to synthesize these opposing forces into what would become his Biosocial Learning Theory.

The DSM Revolution

Millon’s most significant institutional contribution began in the late 1970s when he was invited to join the Task Force for the DSM-III. At the time, psychiatry was in crisis; diagnoses were unreliable and varied wildly from doctor to doctor. Millon, with his obsession for taxonomy (classification), helped introduce the Multiaxial System.

- Axis I: Acute clinical syndromes (e.g., Depression, Schizophrenia).

- Axis II: Personality Disorders and Mental Retardation.

By creating Axis II, Millon ensured that personality disorders were not seen as “minor” issues but as the context in which all other symptoms occur. He argued that you cannot treat the depression (Axis I) without understanding the personality (Axis II) that sustains it.

II. Theoretical Foundations: Evolution as the Blueprint

Millon’s genius lay in his ability to connect psychology to biology without being reductionist. He asked a simple, profound question: What are the fundamental tasks that every living organism must perform to survive?

The Three Evolutionary Polarities

Millon proposed that all personality styles are derived from how an individual answers three evolutionary questions:

- Existence (Pleasure vs. Pain): Does the organism focus on life enhancement (seeking pleasure) or life preservation (avoiding pain)?

- Example: The Schizoid personality lacks the drive for pleasure (passive-detached), while the Avoidant personality is actively terrified of pain (active-detached).

- Adaptation (Active vs. Passive): Does the organism change its environment to suit its needs (active) or change itself to suit the environment (passive)?

- Example: The Dependent personality passively waits for others to provide, while the Histrionic actively manipulates others to get attention.

- Replication (Self vs. Other): Does the organism focus on nurturing itself (individualism) or nurturing others (nurturance)?

- Example: The Narcissist is purely Self-focused, while the Compulsive (OCPD) is Other-focused (dutiful to rules and authority).

By mapping these polarities, Millon created a “Periodic Table of Personality.” This mathematical symmetry brought order to the chaos of mental health diagnosis.

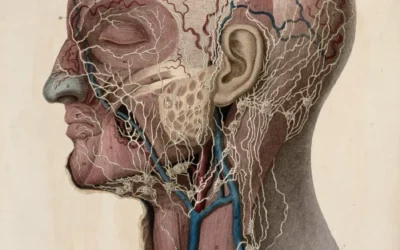

III. Conceptualizing Trauma: The Immune System of the Soul

Unlike modern trauma theorists who often view trauma as a specific event that “breaks” the brain, Millon viewed personality disorders as pathological resilience. He argued that a personality disorder is essentially a rigid immune system.

For example, a child raised in a chaotic, abusive home might develop a Paranoid style. In that environment, hyper-vigilance and mistrust are adaptive; they keep the child safe. The “disorder” occurs when the child grows up and continues to use that same strategy in a safe environment where it is no longer necessary. Millon taught that we should not pathologize the defense; we should honor it as a survival tool that has outlived its usefulness.

Views on Contemporaries

- Sigmund Freud: Millon respected Freud’s insight into the internal conflict but rejected his “hydraulic” model of libido. He replaced Freud’s psychosexual stages with evolutionary stages.

- Carl Jung: While Millon was more empirical than Jung, he shared Jung’s appreciation for opposites and polarities. Millon’s “Self vs. Other” polarity mirrors Jung’s Introversion vs. Extroversion.

- Alfred Adler: Millon was arguably closest to Adler in his emphasis on social adaptation. Like Adler, he believed that all behavior is goal-directed and socially embedded.

IV. The Millon Subtypes of Borderline Personality Disorder

Millon is perhaps most famous for his granular breakdown of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). He rejected the idea that BPD was a “garbage bin” diagnosis. He identified four distinct subtypes, each representing a different collision of the evolutionary polarities.

1. The Discouraged Borderline (Avoidant + Depressive)

These individuals are characterized by submissiveness and loyalty. They feel vulnerable and constantly in danger of abandonment. They do not act out with rage but with despair.

Therapeutic Focus: Rebuilding a sense of self-efficacy and reducing dependency. This aligns with treating Dependent Personality traits.

2. The Impulsive Borderline (Histrionic + Antisocial)

These are the thrill-seekers. They are seductive, capricious, and terrified of boredom. Their instability is driven by a need for constant external validation to prove they exist.

Therapeutic Focus: Impulse control and distress tolerance, often utilizing DBT skills.

3. The Petulant Borderline (Passive-Aggressive + Negativistic)

Defined by unpredictability and irritability. They are the “complaining” borderlines who feel cheated by life. They are defiant and stubborn, often sabotaging their own happiness to prove a point.

Therapeutic Focus: Addressing the underlying resentment and the “victim” narrative.

4. The Self-Destructive Borderline (Depressive + Masochistic)

The “inward-turning” borderline. They are conforming and deferential but harbor intense self-hatred. They may be high-functioning socially while privately engaging in severe self-harm.

Therapeutic Focus: Working with the neurobiology of shame and internalized anger.

V. The Legacy: Mathematics and Measurement

Millon was not content to just theorize; he wanted to measure. He developed the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI), now in its fourth edition (MCMI-IV). Unlike the MMPI, which was designed to diagnose acute conditions (like Schizophrenia), the MCMI was specifically designed to map the architecture of personality disorders.

This tool brought mathematical rigor to depth psychology. It allowed clinicians to see the mix of traits—for example, a patient might be 70% Narcissistic and 30% Antisocial. This nuance is critical for treatment planning, moving beyond binary “have it or don’t” diagnoses.

The End of an Era

Millon died in 2014, leaving behind a legacy that is both foundational and increasingly endangered. As psychiatry moves toward a purely biological model (genes and neurotransmitters), Millon’s “Biosocial” model—which honors the story, the struggle, and the strategy of the person—is more vital than ever.

Bibliography

- Millon, T. (1969). Modern Psychopathology: A Biosocial Approach to Maladaptive Learning and Functioning. Saunders.

- Millon, T. (1981). Disorders of Personality: DSM-III: Axis II. Wiley.

- Millon, T. (1990). Toward a New Personology: An Evolutionary Model. Wiley.

- Millon, T., & Davis, R. D. (1996). Disorders of Personality: DSM-IV and Beyond. Wiley.

- Millon, T. (2011). Disorders of Personality: Introducing a DSM/ICD Spectrum from Normal to Abnormal. Wiley.

- Millon, T., & Grossman, S. (2007). Moderating Severe Personality Disorders: A Personalized Psychotherapy Approach. Wiley.

- Strack, S. (Ed.). (2006). Differentiating Normal and Abnormal Personality. Springer (Dedicated to Theodore Millon).

0 Comments