A psychological tour through the Magic City’s strangest, most forgotten, and most revealing history

Birmingham likes to call itself the Magic City, but magic implies illusion, and what’s truly strange about this place is how much of its real history has simply vanished from collective memory. As a therapist practicing in the Birmingham area, I’ve noticed something: the things we forget about our hometown often reveal more about us than the things we remember.

Here are twenty facts about Birmingham and Alabama that most locals have never heard, and what each one teaches us about memory, identity, and why places haunt us the way they do.

1. George Ward Built a Greek Temple in Birmingham, and All That’s Left Is an Orange Roll Recipe

In the early 1900s, Birmingham Mayor George Ward constructed an elaborate Sibyl Temple on his estate, complete with classical columns and a resident “sibyl” who served visitors prophetic-looking orange rolls. The temple is long gone. The orange rolls survive at several Birmingham restaurants to this day.

What it means: Sometimes the peripheral detail outlasts the monument. In therapy, we call this displacement, and it’s often where the real meaning hides.

[Read the full story: The Psychology of Orange Rolls: Why a Pastry Outlasted a Temple →]

2. Vulcan’s Bare Backside Was Visible to All of Birmingham for Decades

Giuseppe Moretti’s famous Vulcan statue, the largest cast-iron statue in the world, was originally displayed at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis facing backwards, his unclothed posterior greeting visitors. When Birmingham finally installed him on Red Mountain, his rear end faced the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods for years.

What it means: What we display says less about us than what we accidentally reveal.

[Read the full story: Vulcan’s Original Butt: The Strange History of Birmingham’s Statue →]

3. Mountain Brook Was Built on the Grounds of a Psychiatric Facility

The Jemison family, who developed Mountain Brook into one of America’s wealthiest suburbs, originally operated a private psychiatric facility on part of the land. The same family shaped Alabama’s mental health policy for generations, with consequences that echoed through the Wyatt v. Stickney case and beyond.

What it means: The foundations we build on are never as clean as the developments that cover them.

4. Mountain Brook’s English Cottage Architecture Was a Deliberate Fantasy

Drive through Mountain Brook and you’ll notice something unusual: Tudor revivals, English cottages, and storybook architecture everywhere. This wasn’t coincidence. Robert Jemison Jr. and his planners deliberately imported a romanticized English village aesthetic to create an idealized pastoral escape from industrial Birmingham, complete with winding lanes named after English places. The architecture sells a fantasy of old-world gentility in a city that was barely fifty years old when these homes were built.

What it means: Sometimes we build the past we wish we had rather than acknowledge the present we’re living in.

[Read the full story: Mountain Brook Architecture →]

5. Mountain Brook Was Intentionally Designed Without Sidewalks

This wasn’t an oversight or budget constraint. Robert Jemison Jr. deliberately planned Mountain Brook’s winding streets without pedestrian infrastructure, creating what urbanist Leon Krier would later call “intimate atomization,” beautiful isolation disguised as pastoral charm.

What it means: Sometimes the infrastructure we don’t build shapes us more than what we do.

[Read the full story: Mountain Brook Sidewalks: The Hidden Psychology of Isolation by Design →]

6. Highway 280 Was Designed as a Bypass, Not a Destination

The sprawling commercial corridor that defines so much of Birmingham’s eastern suburbs was never meant to be a place. It was engineered as a way to avoid places, and its design continues to shape how disconnected those communities feel from the urban core.

What it means: When we build systems to bypass difficulty, we often bypass meaning along with it.

7. Your Homewood Street Runs Diagonal Because of a Railroad That No Longer Exists

If you’ve ever wondered why Homewood’s grid doesn’t align with the compass, the answer is the old Birmingham Mineral Railroad, a transportation system so fundamental to the area’s development that its ghost still dictates which direction your house faces.

What it means: We orient ourselves around structures long after those structures disappear.

8. Birmingham Had a Complete Streetcar System Until 1953, Then Chose to Forget It

The Birmingham Electric Company operated an extensive network of streetcars connecting downtown to Homewood, Mountain Brook, Vestavia, and beyond. The system didn’t fail. It was deliberately dismantled. Most Birmingham residents today have no idea it ever existed.

What it means: Collective amnesia about what was taken from us is its own form of grief.

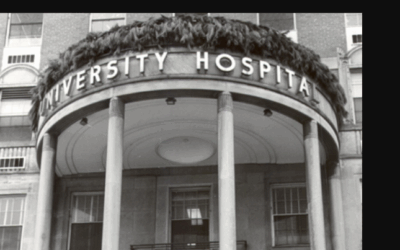

9. UAB Didn’t Exist as a University Until 1969

The institution that now dominates Birmingham’s economy, employs over 23,000 people, and anchors the city’s identity was a mere extension center until it achieved independence. Birmingham’s flagship institution is younger than most of its faculty.

What it means: Identity isn’t about origins. It’s about what we become when no one expected us to.

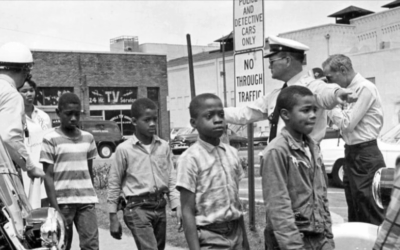

10. The Children’s March Changed History Because Adults Couldn’t Risk What Kids Could

In May 1963, over a thousand Birmingham children left school to march for civil rights because the movement’s adult members couldn’t afford to lose their jobs or face longer jail sentences. The children faced fire hoses and police dogs while their parents watched.

What it means: When systems are broken enough, children end up carrying what adults cannot bear.

11. The Cahaba Lily Only Blooms for Two Weeks, and Only in Alabama

The Cahaba lily, one of the rarest flowers in North America, exists almost exclusively in Alabama’s Cahaba River and blooms for a vanishingly brief window each May. Miss it, and you wait another year.

What it means: Some things cannot be captured, scheduled, or optimized. Some things teach us to show up.

12. Kudzu Was Deliberately Imported and Promoted by the U.S. Government

That vine swallowing abandoned buildings and telephone poles across Alabama wasn’t an accident or an invasion. The Soil Conservation Service actively paid Southern farmers to plant kudzu throughout the 1930s and 1940s, promoting it as a miracle solution for erosion control. By the time officials realized their mistake, kudzu had established itself across millions of acres. Alabama’s most infamous plant is a monument to the law of unintended consequences.

13. The Ladybugs in Your House Every Fall Are an Imported Species That Displaced the Native Ones

Those orange beetles clustering on your windows each October aren’t the friendly native ladybugs you grew up with. They’re Asian lady beetles, deliberately released by the USDA throughout the twentieth century to control agricultural pests. The program worked too well. The imported beetles outcompeted native ladybug species across the Southeast, and now they invade Alabama homes by the thousands each autumn, leaving behind a distinctive smell and occasionally biting. The ladybug you remember from childhood is increasingly rare.

14. The Fish Market Served Fine Seafood on Paper Plates for Decades, On Purpose

George Sarris’s legendary Birmingham restaurant deliberately used disposable plates while serving some of the best seafood in the South. It wasn’t about cost. It was about confidence.

What it means: When you know what you are, you don’t need the trappings that prove it.

15. Birmingham Once Claimed “The Heaviest Corner on Earth”

In the early 1900s, the intersection of 1st Avenue North and 20th Street held four of the tallest buildings in the South, and Birmingham boosters genuinely claimed it was the heaviest corner on Earth. The claim was always more aspiration than fact.

What it means: Sometimes the stories we tell about ourselves reveal the insecurities we’re trying to outrun.

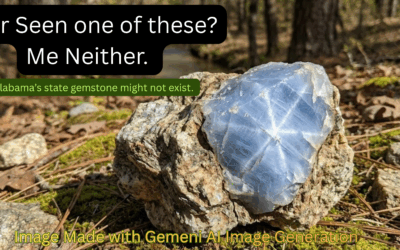

16. Alabama’s State Gemstone Might Not Actually Exist

Star blue quartz was designated Alabama’s official state gemstone in 1990. The problem: geologists have struggled to verify that the stone occurs naturally in Alabama at all. The designation may have been based on wishful thinking.

What it means: We sometimes legislate what we wish were true rather than face what is.

[Read the full story: Does Alabama’s State Gemstone Actually Exist? →]

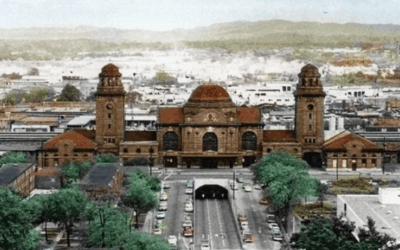

17. Birmingham Demolished Its Grand Terminal Station, Then Spent Decades Grieving It

In 1969, Birmingham tore down its magnificent Terminal Station, a Beaux-Arts masterpiece that had welcomed travelers for sixty years. The city has never stopped mourning the decision, or stopped making similar ones.

What it means: We often destroy what we love most, then spend our lives wondering why.

18. Niki’s West Cafeteria Accidentally Created the Most Psychologically Democratic Space in Birmingham

The legendary cafeteria’s combination of communal tables, forced proximity, and come-as-you-are service created something rare: a space where Birmingham’s rigid social boundaries temporarily dissolved. It was never designed that way.

What it means: The spaces that heal us are rarely the ones we plan.

[Read the full story: Niki’s West Cafeteria: The Accidental Psychology of Democratic Space →]

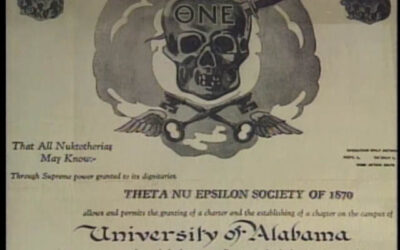

19. “The Machine” at the University of Alabama Is Real, and That Changes Everything

Alabama’s not-so-secret secret society has controlled student government, Greek life, and political pipelines for generations. Unlike most conspiracy theories, this one is documented, admitted, and ongoing.

What it means: When the conspiracy is real, the psychological effects are different, and often worse, than when it’s imagined.

20. Alabama’s Ghost Stories Follow a Specific Psychological Pattern

From Sloss Furnaces to countless antebellum houses, Alabama’s ghost stories tend to cluster around particular types of locations and traumas. The pattern reveals less about the supernatural and more about what the South has been unable to process.

What it means: We haunt ourselves with the griefs we refuse to name.

What These Facts Share

Every one of these forgotten, strange, or suppressed pieces of Birmingham history points to the same truth: places are psychological. The infrastructure we build, the monuments we erect, the species we import, the systems we dismantle, and the stories we stop telling, all of it shapes who we become and what we’re capable of feeling.

Birmingham isn’t unique in having buried history. But it might be unique in how much that buried history still shapes daily life in Homewood, Mountain Brook, Vestavia Hills, and the city itself.

Understanding where we live is the beginning of understanding ourselves.

Joel Blackstock is a Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker and Clinical Director of Taproot Therapy Collective, providing psychotherapy services in Hoover, Alabama, serving clients throughout the Birmingham metro area including Homewood, Mountain Brook, Vestavia Hills, and surrounding communities.

0 Comments