When Trauma Looks Like Schizophrenia: What I Learned Working with Psychosis

The line between “broken brain” and “shattered self” is far blurrier than psychiatry admits.

Key Points:

- Up to 80% of people diagnosed with schizophrenia have histories of severe childhood trauma.

- The “origin story” a patient tells about their symptoms often reveals whether trauma or genetics is the primary driver.

- Trauma survivors who hear voices often describe spirits and possession; their symptoms may actually be dissociated parts of themselves.

- Understanding this distinction changes everything about treatment—and makes recovery possible for many who were told they’d be sick forever.

The Question Nobody Was Asking

When I started my career as a social worker at UAB REACT in Birmingham, Alabama, I noticed something that nobody seemed to be talking about. The patients diagnosed with schizophrenia fell into two very different groups, and once I saw the pattern, I couldn’t unsee it.

The first group had devastating trauma histories. Sexual abuse. Confinement. Violence in the home. When these patients described their psychotic experiences, they told me about spirits that had entered their bodies, about their souls being swapped with someone else’s, about demons that whispered commands in voices that sounded like their abusers. Their eyes were flat, their affect numbed—but underneath that stillness, you could sense a storm.

The second group was different. Their families had histories of mental illness. Their decline had been gradual—a slow withdrawal from friends, a quiet slipping in school performance, an increasing difficulty following conversations. When they described their experiences, they talked about machines, surveillance systems, algorithms tracking them. Their affect wasn’t numbed; it was genuinely diminished, as if someone had turned down the volume on their emotional life.

I kept asking: Are these really the same illness?

Years later, I’ve come to believe the answer is no. And this distinction matters enormously—because when we treat trauma as if it were a genetic brain disease, we often make people worse instead of better.

The Uncomfortable Statistics

Here’s what the research says, even though most psychiatric training still minimizes it:

Between 50% and 80% of people diagnosed with schizophrenia report significant childhood trauma—rates far higher than the general population or other psychiatric conditions. Sexual abuse, physical abuse, and severe neglect are dramatically overrepresented. And here’s the kicker: there’s a dose-response relationship. The more types of trauma someone experiences, the higher their risk of developing psychosis. Five or more adverse childhood experiences makes someone exponentially more likely to hear voices or develop paranoid beliefs than someone with none.

This isn’t correlation. This is causation-level association—comparable to the link between smoking and lung cancer.

Yet when I was trained, we were taught that the content of delusions didn’t matter. Whether someone believed they were Jesus, a CIA target, or possessed by demons—it was all just “neural noise,” symptoms of an underlying brain disease. The trauma history? Noted in the chart, then largely ignored in treatment planning.

This approach, I’ve come to believe, has caused immense unnecessary suffering.

Two Different Wounds, Two Different Stories

The most useful clinical insight I’ve developed is this: listen to the origin story.

When a patient describes what’s happening to them, they’re not just reporting random symptoms. They’re telling you a story about how their mind was wounded. And that story often reveals whether trauma or neurodevelopment is the primary driver.

The Spirit Wound: Trauma’s Signature

Patients with severe interpersonal trauma—especially sexual abuse and confinement—tend to describe their experiences in relational, embodied, and often spiritual terms:

“Something entered me.”

“My soul was swapped with someone else’s.”

“Spirits speak to me—they know what happened.”

“This body doesn’t belong to me.”

These aren’t random delusions. They’re literalized descriptions of what dissociation feels like from the inside.

Think about it: What happens when a child is being violated and cannot escape? The only exit is mental. The mind separates from the body: “This isn’t happening to me. I’m not here. This body isn’t mine.” This is adaptive. It’s survival. But when the trauma is severe enough and repeated enough, this emergency defense becomes structural. The personality fragments into parts—some that hold the trauma, some that try to function in daily life.

Years later, those dissociated parts don’t disappear. They break through as voices, as presences, as the sensation of being controlled by something other. Because they feel other—because they hold experiences the conscious self cannot integrate—they’re naturally interpreted as spirits, demons, or possessing entities.

Julian Jaynes, in his fascinating theory of the “bicameral mind,” suggested that ancient humans experienced their own thoughts as external voices—commands from gods or ancestors. Trauma, in this view, can cause a kind of regression to this earlier mode of consciousness. The “spirits” are real in the sense that they’re genuinely dissociated aspects of the self. They’re just not external.

The Machine Wound: Modernity’s Signature

Patients without significant trauma histories—those with strong genetic loading, gradual onset, and what clinicians call “deficit” presentations—tend to describe their experiences very differently:

“There’s a chip in my brain.”

“The algorithm is tracking me specifically.”

“I’m in a simulation.”

“My thoughts are being broadcast through Wi-Fi.”

These delusions are technological, abstract, and cold. They describe control, but it’s impersonal control—systems rather than relationships, machines rather than beings.

Research shows that technology-themed delusions have increased dramatically—about 15% per year between 2016 and 2024. Over half of patients in modern cohorts now incorporate the internet into their delusional systems.

This makes sense. The form of psychosis—the experience of being watched, controlled, influenced—seems to be biological, built into the hardware of how psychosis works. But the content—what the person believes is doing the watching—reflects the cultural vocabulary available to them. In the medieval period, it was demons. In the industrial age, it was magnets and electrical rays. In the Cold War, it was the CIA and radio transmitters. Now it’s algorithms and simulation theory.

The psychiatrist Victor Tausk noticed this pattern over a century ago. He described patients who believed they were controlled by elaborate machines—looms, batteries, gears—and suggested the “machine” was actually a projection of their own body, which had become alien to them. The machine delusion is the mind’s attempt to explain its own dysfunction to itself.

The Flat Affect Confusion

Here’s where things get clinically crucial, and where I see the most diagnostic errors.

Both trauma survivors and patients with genetic schizophrenia can present with “flat affect”—that blunted, emotionless presentation that psychiatry calls a “negative symptom.” But they’re not the same thing at all.

Shutdown vs. Deficit

Trauma survivors show “shutdown dissociation.” This is a freeze response—the nervous system’s emergency brake when fight and flight have both failed. The person looks flat on the outside, but internally they’re often flooded with emotion they can’t express. This is the dorsal vagal response that polyvagal theory describes—the ancient “playing dead” circuit that mammals use as a last resort.

Crucially, shutdown dissociation fluctuates. The same patient who seems emotionally dead in one session may show intense emotion in another—especially when they feel safe, or when a different “part” of their personality emerges. Their flat affect is a defense, not a deficit.

Genetic patients show “deficit syndrome.” This is something different—a genuine reduction in the capacity for emotional experience and expression. It’s associated with measurable neurological changes: synaptic pruning, reduced prefrontal activity, declining cognitive function. This flat affect doesn’t fluctuate. It’s stable, enduring, and doesn’t respond much to environmental changes.

The trauma survivor with shutdown dissociation has a storm inside a shell. The deficit patient has a quieter internal world—fewer thoughts, less emotional weather, a genuine “poverty of content.”

Treating these as the same thing is a clinical disaster. Antipsychotics may help quiet the deficit patient’s disorganized thinking. But for the trauma survivor, they often make things worse—adding the sedating side effects of medication on top of the dissociative shutdown, creating a double layer of numbing that prevents the trauma processing that could actually help.

Two Different Roads to the Break

The distinction becomes even clearer when you look at how patients arrive at their first psychotic episode.

The Stormy Path (Trauma)

Trauma-driven psychosis tends to have a “stormy” prodrome—the period of disturbance before the full break. You see:

High anxiety and mood swings. Sleep disturbances, especially nightmares. Dissociative experiences—feeling unreal, depersonalized, sensing presences. Substance use as self-medication. Interpersonal chaos.

The onset is often triggered—a breakup, leaving home, a conflict that echoes the original trauma. The person was holding it together, barely, and then something cracked the container.

The Quiet Path (Genetic)

Genetic psychosis tends to have a “quiet” prodrome. You see:

Gradual social withdrawal. Declining academic or work performance. Cognitive slippage—trouble following conversations, understanding metaphors, thinking clearly. Loss of motivation and ambition.

This often begins years before any obvious psychotic symptoms appear. There’s no clear trigger. The person seems to be slowly fading rather than dramatically breaking.

Why This Distinction Matters for Treatment

If schizophrenia is a single disease caused by broken brain hardware, then treatment is straightforward: medication to fix the hardware, forever.

But if a significant portion of “schizophrenia” is actually severe dissociation caused by trauma, then treatment needs to be completely different.

The Problem with One-Size-Fits-All

Antipsychotics work by blocking dopamine. For someone whose dopamine system is genuinely dysregulated due to neurodevelopmental problems, this can help restore balance. But for someone whose “dopamine dysregulation” is actually a sensitized stress response created by childhood trauma, you’re treating the symptom while ignoring the cause.

Worse, by sedating the “voices”—which are actually dissociated parts of the person’s own psyche—you prevent those parts from being heard, understood, and integrated. The patient becomes quieter, more compliant, more “stable.” But they don’t heal. They just become better at suppressing the parts of themselves that need attention most.

I’ve seen patients who spent years heavily medicated, labeled “treatment-resistant schizophrenia,” who made dramatic progress when someone finally said: “Tell me about those voices. What do they say? Do they remind you of anyone?”

What Actually Helps

For trauma-driven psychosis, what helps is trauma treatment—approaches like Brainspotting, Emotional Transformation Therapy, EMDR, Internal Family Systems, and somatic therapies that can safely access and process the dissociated material.

This means not immediately trying to eliminate the voices, but approaching them with curiosity. Research on “voice dialogue” approaches shows that when patients learn to engage with their voices as parts of themselves—understanding what they need, what they’re protecting against, what they’re trying to communicate—the voices often become less hostile and controlling.

It also means using tools like qEEG brain mapping to see what’s actually happening neurologically. Trauma and genetic psychosis look different on a brain map. We can literally see whether we’re dealing with a sensitized stress response or a neurodevelopmental pattern—and target treatment accordingly.

Two Illnesses, One Medication, Different Needs

Here’s the uncomfortable possibility: what we call “schizophrenia” may actually be two different illnesses—or a spectrum of illnesses—that happen to respond to the same medication.

Antipsychotics work on dopamine. Both trauma-driven and genetically-driven psychosis involve dopamine dysregulation, just through different pathways. In trauma, the dopamine system becomes sensitized by chronic stress. In genetic cases, there may be constitutional abnormalities in dopamine signaling. Either way, blocking dopamine receptors reduces the intensity of positive symptoms—the voices, the paranoia, the delusions. So both groups get the same prescription.

Standard treatment also emphasizes psychoeducation: teaching patients about their “brain disease,” the importance of medication compliance, recognizing warning signs of relapse. This is genuinely helpful for many patients—understanding what’s happening to you reduces fear and increases agency.

But here’s what’s missing: for patients whose psychosis is partially or primarily trauma-driven, psychoeducation about “your brain disease” may actually be counterproductive. It teaches them to view their symptoms as meaningless malfunction rather than meaningful—if dysregulated—responses to overwhelming experience. It doesn’t address the underlying wound.

These patients don’t just need medication management and relapse prevention. They need trauma therapy. They need someone to help them process what happened, integrate the dissociated parts of themselves, and rebuild a sense of safety in their bodies and relationships. Without this, we’re essentially giving someone painkillers for a broken bone without ever setting the bone. The pain is managed, but healing never happens.

This doesn’t mean abandoning medication—many trauma survivors benefit from the stabilization that antipsychotics provide, especially in acute phases. But it means recognizing that medication is a floor, not a ceiling. For the traumagenic subgroup, the real work happens in therapy.

The Spectrum Model

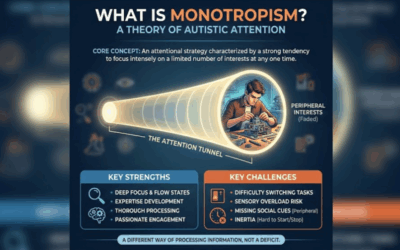

The best way to think about this isn’t “either/or” but “spectrum.”

On one end: Pure traumagenic psychosis. Severe childhood trauma, clear dissociative features, “spirit” or “body-swap” origin myths, stormy onset, fluctuating symptoms. This may represent 40-50% of current schizophrenia diagnoses.

On the other end: Pure genogenic psychosis. Strong family history, no clear trauma, gradual onset, deficit symptoms, technological or abstract delusions. This may represent 15-20% of diagnoses.

In the middle: Hybrids. Genetic vulnerability plus environmental triggers—cannabis use, migration stress, urban isolation—that tip a sensitive system into psychosis. The remaining 30-40%.

Genetic research supports this spectrum view. There’s no single “schizophrenia gene.” The same genetic variants that increase schizophrenia risk also increase risk for bipolar disorder, ADHD, and autism. What seems to be inherited isn’t a specific disease, but a sensitive dopamine system—one that might manifest as different conditions depending on what happens to it.

Listening to the Origin Myth

I’ve learned to pay close attention to the story a patient tells about what’s happening to them.

When someone describes spirits, possession, body-swapping, or forces that feel intimately connected to their history—I’m listening for trauma. The violation was human and relational, so the explanation remains human and relational.

When someone describes machines, algorithms, surveillance systems, or abstract forces with no relational quality—I’m considering whether this might be a more “endogenous” process, or perhaps a response to the alienation of modern life rather than specific interpersonal trauma.

Neither presentation is “better” or “worse.” But they require different approaches, different emphases in treatment, and different prognostic expectations.

The Hope in This Distinction

Here’s what matters most: trauma-driven psychosis is often treatable in ways that “genetic” schizophrenia is not.

This isn’t about blame—”it’s your trauma, not real illness.” It’s about hope. If your voices are dissociated parts of yourself, they can be heard, understood, and integrated. If your flat affect is shutdown dissociation, your emotional life can return when your nervous system feels safe enough. If your paranoia is hypervigilance learned in a dangerous childhood, you can learn that not everyone is a threat.

The patients I saw at UAB REACT who carried the heaviest trauma often had the most dramatic recoveries—when they finally received treatment that addressed what had actually happened to them, rather than just medicating their symptoms into submission.

The spirits, it turned out, had something to say. They just needed someone willing to listen.

Joel Blackstock is a Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker (LICSW-S) and Clinical Director of Taproot Therapy Collective in Birmingham, Alabama. He specializes in complex trauma treatment using qEEG brain mapping, Brainspotting, Emotional Transformation Therapy, and somatic approaches.

References

- The Traumagenic Neurodevelopmental Model of Psychosis Revisited – Aarhus University

- The Association Between Early Traumatic Events and Schizophrenia – PubMed Central

- Pathways Associating Childhood Trauma to the Neurobiology of Schizophrenia – PubMed Central

- The Contribution of Early Traumatic Events to Schizophrenia – PubMed

- What Is the Link Between Trauma and Schizophrenia? – Medical News Today

- Can Schizophrenia Be Caused by Trauma? – Charlie Health

- Trauma Splitting and Structural Dissociation – Eggshell Therapy

- Bicameral Mentality – Wikipedia

- Hearing Voices and Dissociation – Dirk Corstens

- The Algorithm Is Hacked: Analysis of Technology Delusions – Cambridge University Press

- Psychotic Delusions Are Evolving to Incorporate Smartphones – PsyPost

- Childhood Trauma and Prodromal Symptoms – PubMed Central

- Prodromal Symptoms of Schizophrenia – Psychiatric Times

- Common Genes Responsible for ADHD, Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder – Karolinska Institutet

- Shared Genetic Background Between Parkinson’s Disease and Schizophrenia – PubMed Central

- Faraway So Close: Schizophrenia and Dissociation – PubMed Central

- Mental Health’s Stalled Biological Revolution – MIT Press

0 Comments