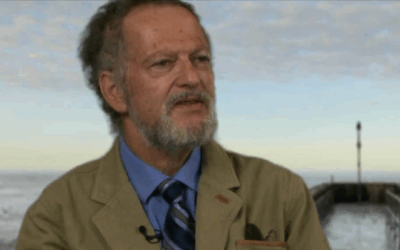

In 1982, Richard Schwartz, a young, zealous family therapist fresh from his PhD at Purdue University, designed an outcome study he believed would prove family therapy had found the holy grail of psychological treatment. He recruited thirty bulimic teenagers and their families for what he anticipated would be a triumphant demonstration of systemic intervention. Family therapy, rooted in the systems thinking of Gregory Bateson, Murray Bowen, and Salvador Minuchin, held that individual pathology couldn’t be understood in isolation. Problems resided not in the individual mind but in family dynamics, communication patterns, and relational structures. Fix the family system, the theory promised, and the symptom would resolve.

Schwartz, brimming with the conviction that comes from recent doctoral training, applied structural and strategic family therapy techniques with precision. He worked to reorganize hierarchies, interrupt problematic sequences, reframe symptoms, shift alliances. He addressed the eating disorder as family-level dysfunction requiring family-level solution. The families engaged earnestly. Schwartz worked diligently.

The results were devastatingly clear: despite reorganizing family systems, despite skillful therapeutic intervention, his clients continued to binge and purge. Family therapy, in which Schwartz had invested his professional identity and theoretical allegiance, wasn’t working. Confronted with this failure, he could have doubled down on theory, attributing poor outcomes to resistant families or his own inexperience. Instead, he did something that would fundamentally transform psychotherapy: he set aside his theoretical assumptions and asked his clients what was actually happening inside them.

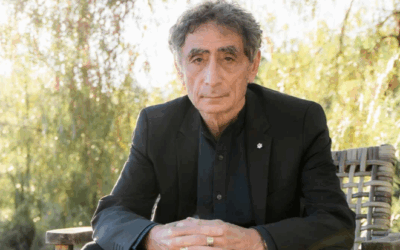

“Why do you keep bingeing and purging even though we’re making progress with your family?” he asked, expecting perhaps to hear about family stress, unresolved conflicts, or therapeutic resistance. What he heard instead changed everything. His clients described inner conflicts not as vague urges or impulses but as distinct voices, separate parts of themselves engaged in heated internal debates. One young woman, when pressed to differentiate these voices, identified several regular participants.

There was a harsh critic obsessively focused on her appearance, scrutinizing every physical flaw. A defender blamed her parents or the eating disorder itself for her problems, protecting her from the critic’s attacks. A sad, hopeless, helpless part felt overwhelmed by the conflict. And finally, there was a part that “took over” and made her binge, seemingly operating with autonomy separate from her conscious will. These weren’t metaphors or loose descriptions. They were, his client insisted, distinct aspects of herself, each with characteristic voice, perspective, and agenda.

As Schwartz listened more carefully to his bulimic clients, to survivors of sexual abuse, to people with depression and anxiety, he heard variations on the same theme. People spontaneously described themselves using parts language. “Part of me wants to recover but another part says I don’t deserve it.” “Part of me knows it wasn’t my fault but another part feels ashamed.” “Part of me is terrified of relationships and part of me desperately wants connection.” This wasn’t unusual or pathological. It was, Schwartz came to realize, how the mind naturally organizes itself.

The recognition struck him as both revolutionary and obvious. Of course people have parts. Anyone who has experienced internal conflict, who has wanted two contradictory things simultaneously, who has felt taken over by anger or fear or shame despite conscious intention, knows the experience of multiplicity. What was revolutionary was recognizing this multiplicity as the mind’s normal structure rather than as pathology requiring integration or resolution.

Schwartz noticed something else that would prove crucial: the parts resembled family members in their interactions. They formed alliances, battled for dominance, took on protective roles, became polarized. The critic and the defender were locked in escalating conflict, each believing it had to be more extreme to counter the other. The sad, hopeless part was exiled, banished from awareness because its pain threatened to overwhelm the system. The bingeing part served as firefighter, desperately trying to extinguish the flames of unbearable emotion through impulsive action.

This observation connected his family therapy training to inner experience. If families operated according to systemic principles, patterns, feedback loops, homeostasis, resistance to change, and parts did the same, perhaps the same therapeutic interventions that worked with families could work with internal systems. The tools of structural and strategic family therapy, joining, reframing, enactment, unbalancing, could be applied to the relationships between parts.

What happened when Schwartz began working with parts rather than trying to eliminate symptoms proved remarkable. When he approached the bingeing part not as behavior to be stopped but as protector with legitimate concerns, it would explain its function. It was trying to help. The overwhelming emotions felt dangerous. Bingeing provided relief, numbness, distraction. It was

desperately fighting the flames of exiled pain. When Schwartz acknowledged this protective intention, expressed curiosity about the part’s experience, the part would soften. It didn’t want to cause harm. It was doing the best it could with limited options.

Most crucial was Schwartz’s discovery of what he came to call Self. When parts felt safe, when they trusted that someone was attending to them with curiosity rather than judgment, they would step back, creating space. In that space, something else emerged. Schwartz found that beneath the warring parts, beneath the protective strategies and exiled pain, every person possessed what he termed “Self energy” characterized by eight C-qualities: Calmness, Curiosity, Clarity, Compassion, Confidence, Courage, Creativity, and Connectedness.

This Self wasn’t another part. It was, Schwartz proposed, the person’s core or true essence, an undamaged quality of awareness present even in people with severe trauma and fragmentation. Unlike parts, which carried burdens and operated from fear and protection, Self possessed natural capacity for healing and leadership. The goal of therapy wasn’t eliminating parts or achieving fusion but helping Self take the lead, allowing parts to trust Self’s guidance rather than battling for control.

This discovery challenged fundamental assumptions in psychotherapy. Psychoanalysis saw the ego as fragile structure requiring strengthening against the id’s primitive drives. Cognitive therapy targeted distorted thoughts requiring correction. Behavioral therapy focused on maladaptive behaviors needing replacement. Schwartz was proposing something radically different: everyone already possesses the internal resources for healing. The problem isn’t deficiency requiring correction but protective parts preventing Self from leading.

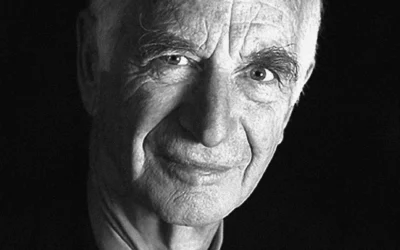

Richard C. Schwartz was born September 14, 1949. He earned his PhD in marriage and family therapy from Purdue University, then launched his career as associate professor at the Institute for Juvenile Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He later joined The Family Institute at Northwestern University as associate professor, teaching family therapy and working with families while developing what would become Internal Family Systems.

His academic position allowed him to refine the theoretical framework while maintaining active clinical practice. By the mid-1980s, he had begun teaching IFS concepts, initially integrated within family therapy training. The response from students and supervisees proved enthusiastic. People recognized their own internal experience in the parts framework. The language of parts normalized what previously felt pathological, confusing internal conflicts reframed as understandable system dynamics.

Schwartz co-authored with Michael Nichols Family Therapy: Concepts and Methods, which became the most widely used family therapy textbook in the United States. This mainstream academic success provided credibility as he developed the more unconventional Internal Family Systems model. He published Internal Family Systems Therapy through Guilford Press in 1995, providing comprehensive introduction to the approach for therapists and academics.

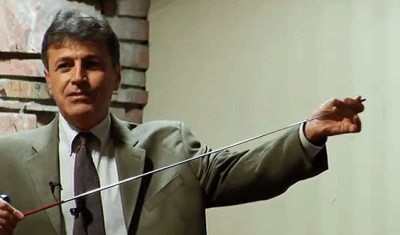

The book described three main categories of parts. Exiles carry psychological trauma, typically from childhood, holding pain, fear, shame, worthlessness. These parts become isolated because their emotions threaten to overwhelm the system. They are exiled, locked away, kept from conscious awareness because what they carry feels unbearable. A person may be consciously unaware of these exiled parts but they continue influencing behavior through the protective parts that develop to keep them contained.

Managers serve preemptive protective function. Their goal is preventing exiles from being triggered and flooding consciousness with overwhelming emotion. Managers control how the person interacts with the world. They might make you achieve constantly to prove worthiness, counteracting exiled shame. They might make you please others to avoid rejection. They might make you stay distant from relationships to prevent abandonment pain. They might make you perfect to avoid criticism. Each manager has characteristic strategy for keeping the system safe.

Firefighters react when exiles get triggered despite managers’ best efforts. When overwhelming emotion breaks through, firefighters leap into action with impulsive, reactive behaviors designed to douse the flames. Bingeing, purging, substance abuse, self-harm, rage, dissociation, any behavior that immediately takes you away from unbearable feeling serves firefighter function. These parts aren’t trying to destroy the person. They’re desperately trying to save the person from emotional pain they believe will be lethal.

The polarization between managers and firefighters creates much of the internal conflict people experience. Managers want control, planning, prevention. Firefighters want immediate relief regardless of consequences. The person feels caught between rigid restriction and impulsive abandon, between perfectionism and chaos, between hypervigilance and reckless disregard. Each extreme reinforces the other in escalating feedback loop.

Schwartz’s therapeutic approach involves helping Self become leader of this internal system. The first step requires accessing Self, which involves asking parts to step back temporarily, creating space for Self-energy to emerge. Many people, particularly those with severe trauma, initially struggle to access Self because protective parts don’t trust that anything other than their vigilance keeps the person safe.

The therapist helps by modeling Self energy, approaching the client’s parts with curiosity, compassion, and calm. This external relationship provides template for internal relationships. As clients experience being met without judgment, their parts begin to recognize possibility of different way of relating. The therapist might ask, “How do you feel toward the part that makes you binge?” If the client responds with judgment, “I hate it, it’s destroying my life,” the therapist recognizes this as another part (often a manager) rather than Self. Self feels curious about all parts, recognizing their protective intentions even when their strategies cause harm.

When Self is present, the therapeutic work involves getting to know parts, understanding their concerns, learning what burdens they carry. The process typically follows sequence: First, the client identifies a target part, often starting with a manager or firefighter creating symptoms. Using mindfulness-based techniques adapted from Focusing, developed by Eugene Gendlin, the client locates the part in their body. “Where do you feel the anxiety? Where in your body is the part that makes you binge?”

Once located, Self approaches the part with curiosity. “What does it want you to know? What is it afraid would happen if it stopped doing its job?” The part, feeling heard rather than judged, often reveals its protective function and the exiles it’s protecting. This leads to deeper work with the exiles themselves. When Self is established as leader, capable of holding overwhelming emotions without being destroyed, the protective parts gradually trust that they can allow access to exiles.

Work with exiles involves witnessing their experience, providing what Schwartz calls “retribution,” validating that what happened to them was wrong, offering comfort and protection that wasn’t available when the trauma occurred. Then comes “unburdening,” releasing the beliefs and emotions the exile took on during traumatic experience. An exiled child part might carry belief “I’m worthless, I’m to blame, I’m bad.” These burdens aren’t intrinsic to the part. They were acquired through trauma and can be released.

The unburdening process involves invitation for the exile to release its burden, often using imagery like light, water, wind, or earth to symbolically carry the burden away. This isn’t cognitive reframing or positive thinking. It’s experiential shift occurring when the part trusts it can release what it’s been holding without the person being destroyed. After unburdening, parts naturally assume healthier, age-appropriate roles aligned with their essential qualities rather than extreme protective functions.

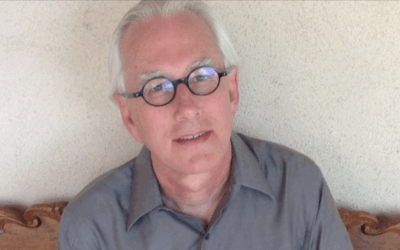

Schwartz founded the Center for Self Leadership in 2000 in Oak Park, Illinois (later renamed the IFS Institute in 2019) to provide training in Internal Family Systems. The organization offers three levels of training, workshops for professionals and general public, an annual conference, and various resources. The IFS Institute has trained thousands of therapists worldwide, with certified practitioners on every continent.

The training emphasizes experiential learning. Trainees work with their own parts, experiencing the model firsthand before applying it with clients. This requirement that therapists do their own parts work distinguishes IFS from many other therapeutic approaches. Schwartz recognized that therapists’ unhealed parts can interfere with therapy, taking over when clients’ parts trigger the therapist’s own exiles or protective systems. By developing their own Self-leadership, therapists can maintain presence and curiosity even when working with extremely challenging material.

Schwartz currently serves as Teaching Associate in Psychiatry at Cambridge Health Alliance, a Harvard Medical School teaching affiliate. He has published more than fifty articles about IFS and authored or co-authored over ten books including Introduction to Internal Family Systems Model, Internal Family Systems Therapy, Internal Family Systems Skills Training Manual (with Frank Anderson and Martha Sweezy), No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model, You Are The One You’ve Been Waiting For: Bringing Courageous Love To Intimate Relationships, The Mosaic Mind: Empowering the Tormented Selves of Child Abuse Survivors (with Regina Goulding), and Many Minds, One Self: Evidence for a Radical Shift in Paradigm (with Robert Falconer).

His book No Bad Parts, published in 2021, brought IFS to broader audience, presenting the model accessibly for general readers rather than just therapists. The book’s title encapsulates core IFS principle: every part has positive intention, even those whose strategies cause tremendous harm. There are no bad parts, only parts forced into extreme roles by circumstances, trauma, and lack of Self-leadership.

The integration between IFS and trauma treatment has proven particularly fruitful. Bessel van der Kolk recognized that the body keeps the score, that trauma lodges in somatic and subcortical systems inaccessible to verbal therapy. IFS provides framework for working with these fragmented traumatic experiences, each exile carrying specific traumatic memory, each protector trying to prevent retriggering.

Janina Fisher’s work on structural dissociation overlaps significantly with IFS. Both recognize that trauma fragments consciousness into distinct self-states. Fisher’s distinction between Apparently Normal Parts and Emotional Parts maps onto Schwartz’s managers and exiles. The integration involves using IFS dialogue with parts while incorporating Fisher’s attention to somatic signals and autonomic states.

Pat Ogden’s Sensorimotor Psychotherapy combines well with IFS by providing body-based interventions for accessing and processing parts. Each part has characteristic posture, gesture, breathing pattern. Working somatically provides entry point when verbal dialogue feels blocked. Someone might notice that when their critic part activates, their shoulders tense and their breathing shallows. Attending to these somatic signals while maintaining Self-leadership allows processing at neurobiological level.

EMDR, developed by Francine Shapiro, can be adapted for parts work. Rather than processing from undifferentiated first-person perspective, the client’s Self witnesses while a specific part receives bilateral stimulation. This prevents overwhelming the system while allowing resolution of traumatic material held by particular exiles.

Brainspotting, developed by David Grand, similarly integrates with IFS. Different parts may have characteristic brainspots, eye positions where their activation intensifies. Processing at those brainspots while maintaining Self presence allows deep work without triggering protective parts into shutdown.

Polyvagal theory, developed by Stephen Porges, provides neurobiological framework for understanding parts. Different parts correspond to different autonomic states. Exiles often operate from dorsal vagal shutdown or sympathetic fight-flight. Managers try to maintain ventral vagal social engagement. Firefighters oscillate between hyperarousal and hypoarousal. Understanding these autonomic patterns helps therapists recognize which parts have activated and what they need.

Allan Schore’s research on right brain affect regulation illuminates why Self-to-part relationships prove so healing. Schore demonstrated that early trauma disrupts right brain development and implicit relational capacities. The compassionate, attuned relationship Self offers to parts provides right brain regulation that was absent during trauma. This allows reorganization of attachment patterns at neurobiological level.

For depth psychology, IFS operationalizes concepts Jung described but struggled to articulate practically. Jung recognized the psyche contains autonomous complexes that can seize control of consciousness. He emphasized the importance of relating to these complexes rather than trying to suppress them. He developed active imagination as method for engaging unconscious contents through dialogue and imagery. IFS provides systematic framework for exactly this work.

The concept of Self in IFS parallels Jung’s Self archetype, the organizing center of the psyche distinct from ego. However, Schwartz’s Self is not developmental achievement requiring individuation process but innate quality present from the beginning, needing only to be accessed rather than created. This democratizes healing, suggesting that everyone already possesses what they need rather than requiring years of analysis to develop Self capacity.

Shadow work, the process of recognizing and integrating disowned aspects of personality, maps directly onto IFS exile work. Shadow material consists precisely of parts that were exiled because they threatened ego identity, carried unbearable shame, or contradicted family values. The IFS process of accessing exiles with Self-compassion, witnessing their experience, validating their reality, and unburdening their shame provides concrete method for shadow integration.

Projection, Jung’s concept that we see our own unconscious contents in others, occurs when parts we haven’t befriended internally get triggered by external resemblance. The person who enrages us carries qualities of our own exiled rage part we haven’t acknowledged. The IFS framework allows recognizing this dynamic and doing the internal work to reclaim projections.

Research on IFS remains limited compared to cognitive-behavioral therapy or EMDR, a criticism that persists. The model lacks large-scale randomized controlled trials demonstrating efficacy for specific disorders compared to active treatments. Most research consists of case studies, qualitative investigations, and small pilot studies showing promise but not definitive evidence.

A 2022 systematic review found that while preliminary evidence suggests IFS may be effective for various conditions including PTSD, depression, anxiety, and eating disorders, methodological limitations of existing studies prevent strong conclusions. Critics note potential for confirmation bias when researchers studying their own therapeutic approach report positive outcomes. The theory’s complexity, with concepts like Self energy, unattached burdens, and guides, makes some aspects difficult to operationalize for rigorous research.

Schwartz has recently discussed accessing Self energy through psychedelic-induced non-dual states, suggesting that substances like MDMA, psilocybin, and ayahuasca can facilitate parts work by creating conditions where Self more easily emerges. This has generated both interest and controversy, with some viewing it as promising integration of cutting-edge neuroscience research on psychedelics and therapy, others expressing concern about encouraging substance use within therapeutic model.

The concept of “unattached burdens,” entities that Schwartz describes as entering people’s systems when they’re out of their body during trauma, abuse, surgery, or psychedelic experiences, and which unlike parts have malevolent intent requiring destruction with fire, has raised skepticism even among IFS practitioners. This moves from psychological metaphor into territory resembling spirit possession, challenging the model’s scientific credibility.

Despite these controversies and limitations, IFS has achieved remarkable cultural penetration. Celebrities including Glennon Doyle, who featured Schwartz on her podcast We Can Do Hard Things for extended multi-part conversations exploring her eating disorder parts, have brought IFS to mainstream audience. The approach has gained enormous popularity on Instagram and TikTok, where therapists and laypeople share parts work experiences and insights.

This popularization carries benefits and risks. The accessibility of parts language allows people to understand their internal experience more compassionately. Someone can recognize “that’s my perfectionist manager” or “my firefighter part is trying to protect me” without pathologizing themselves. However, the simplification required for social media can reduce sophisticated therapeutic approach to catchphrases and memes, potentially trivializing serious trauma work.

The emphasis that all parts are welcome, that no parts are bad, provides powerful antidote to shame. People learn to approach even their most troubling impulses with curiosity rather than condemnation. This proves particularly valuable for trauma survivors who have internalized belief that parts of themselves are irredeemably damaged or evil. IFS offers framework for recognizing that even suicidal parts, self-harming parts, parts that rage or dissociate, are trying to protect, trying to help, operating from limited options developed during overwhelming circumstances.

For couples therapy, Schwartz developed approach detailed in You Are The One You’ve Been Waiting For. Relationship conflicts often involve parts getting triggered and taking over. One partner’s abandonment-sensitive exile activates, triggering anxious clinging manager. This triggers the other partner’s engulfment-fearing exile, activating distancing manager. Each person’s parts react to the other’s parts, creating escalating polarization. When both partners can recognize this dynamic and access Self, they can address each other’s parts with compassion while maintaining leadership of their own systems.

The integration of IFS with various other modalities has created rich landscape of hybrid approaches. Somatic IFS, developed by Susan McConnell, incorporates body-based techniques for accessing and processing parts. EMDR-IFS combinations use bilateral stimulation within parts framework. Neurofeedback-IFS helps clients recognize characteristic brain wave patterns associated with different parts. The flexibility of the model allows creative integration while maintaining core emphasis on Self-leadership and compassionate engagement with parts.

Training programs in graduate schools increasingly incorporate IFS alongside more established approaches. Cambridge Health Alliance, where Schwartz teaches, has integrated IFS into psychiatric residency training. The approach appears in continuing education workshops, trauma treatment conferences, and specialized training programs worldwide. Thousands of therapists have completed formal IFS training, with many more incorporating parts language informally into their practice.

Schwartz lives near Chicago with his wife Jeanne, who serves as Vice President of the IFS Institute, close to his three daughters and six grandchildren. He continues teaching, writing, lecturing, and training while maintaining clinical practice. He serves as Fellow of the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy and sits on editorial boards of professional journals.

His impact on psychotherapy extends beyond those who formally practice IFS. The parts language has become common currency in therapeutic discourse. Therapists across orientations, psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, humanistic, integrate recognition of multiplicity even when not using full IFS protocol. The concept that protective behaviors serve positive intentions, that symptoms reflect parts doing their best rather than pathology requiring elimination, has influenced how many therapists conceptualize problems.

The journey from frustrated family therapist whose bulimia study failed to founder of influential therapeutic model illustrates how clinical innovation often emerges from failure rather than success. Had family therapy worked for those thirty bulimic teenagers, Schwartz might have published confirming outcome study and continued conventional career. Instead, his willingness to set aside theory, listen to clients, follow where their experience led, discovered something that transformed not just his practice but the field.

The core insight remains radical: beneath the warring parts, beneath the protective strategies and exiled pain, beneath the symptoms and struggles, every person possesses undamaged Self capable of healing and leadership. Problems don’t reflect deficiency but parts trying to protect with limited options. The solution isn’t fixing what’s broken but creating conditions where Self can lead and parts can trust.

Whether this proves to be enduring contribution requiring refinement through research or transitional framework eventually superseded by more complete understanding, Schwartz’s work has given millions of people language for their internal experience and method for relating to themselves with greater compassion. From that failed 1982 outcome study to global therapeutic movement, his journey demonstrates that sometimes the greatest discoveries emerge when we’re willing to question our certainties and listen to what people are actually experiencing.

Timeline of Richard C. Schwartz’s Career and IFS Development

1949: Born September 14

1970s: Earned PhD in marriage and family therapy from Purdue University

1981-1982: Conducted bulimia outcome study using family therapy; discovered parts through client reports

Early 1980s: Began developing Internal Family Systems model

1980s: Associate professor at Institute for Juvenile Research, University of Illinois at Chicago

Later 1980s-1990s: Associate professor at The Family Institute, Northwestern University

1995: Published Internal Family Systems Therapy (Guilford Press)

Co-authored Family Therapy: Concepts and Methods with Michael Nichols (became most widely used family therapy text in US)

2000: Founded Center for Self Leadership in Oak Park, Illinois

2000s-2010s: Published multiple books on IFS including Introduction to IFS Model, The Mosaic Mind, You Are The One You’ve Been Waiting For

2019: Center for Self Leadership renamed IFS Institute

2021: Published No Bad Parts bringing IFS to mainstream audience

Present: Teaching Associate in Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School teaching affiliate

Present: Continues training therapists internationally through IFS Institute

Present: Lives near Chicago with wife Jeanne, close to three daughters and six grandchildren

Complete Bibliography of Major Works by Richard C. Schwartz

Schwartz, R. C. (2021). No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model. Boulder, CO: Sounds True.

Schwartz, R. C. (2021). Introduction to Internal Family Systems. New York: Guilford Press.

Schwartz, R. C., Anderson, F. G., & Sweezy, M. (2017). Internal Family Systems Skills Training Manual: Trauma-Informed Treatment for Anxiety, Depression, PTSD & Substance Abuse. Eau Claire, WI: PESI Publishing.

Schwartz, R. C. (2008). You Are The One You’ve Been Waiting For: Bringing Courageous Love To Intimate Relationships. Oak Park, IL: Trailheads Publications.

Schwartz, R. C. & Falconer, R. R. (2017). Many Minds, One Self: Evidence for a Radical Shift in Paradigm. Oak Park, IL: Trailheads Publications.

Schwartz, R. C. & Goulding, R. A. (1995). The Mosaic Mind: Empowering the Tormented Selves of Child Abuse Survivors. Oak Park, IL: Trailheads Publications.

Schwartz, R. C. (1995). Internal Family Systems Therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Nichols, M. P. & Schwartz, R. C. Family Therapy: Concepts and Methods. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Influences and Legacy

Schwartz’s development of IFS drew from multiple sources. Family systems theory from Gregory Bateson, Murray Bowen, Salvador Minuchin, and Virginia Satir provided framework for understanding patterns, feedback loops, and relational dynamics. He applied these systemic principles to intrapsychic experience rather than just family interactions.

Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing method, emphasizing felt sense and body-based awareness, influenced how IFS practitioners help clients locate and experience parts. Buddhist concepts of witnessing consciousness and non-dual awareness informed understanding of Self. Jungian concepts of autonomous complexes and active imagination provided precedent for recognizing multiplicity and engaging unconscious through dialogue.

Gestalt therapy’s emphasis on experiencing and expressing rather than analyzing influenced IFS’s experiential approach. Object relations theory’s attention to internalized representations informed understanding of how early relationships shape internal parts. Yet Schwartz synthesized these influences into genuinely novel framework rather than simply combining existing approaches.

IFS has profoundly influenced contemporary psychotherapy. The parts language has become ubiquitous, used by therapists across orientations. The recognition that protective behaviors serve positive intentions, that symptoms reflect parts doing their best, has shifted how many therapists conceptualize problems. The emphasis on Self-leadership rather than therapist-directed change empowers clients as agents of their own healing.

Integration with trauma treatment modalities including EMDR, brainspotting, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, and Somatic Experiencing has created rich hybrid approaches addressing both psychological and neurobiological dimensions. Work by Janina Fisher, Pat Ogden, and others demonstrates IFS compatibility with somatic and subcortical trauma processing.

For depth psychology, Schwartz provides operational framework for concepts Jung described but struggled to implement systematically. The work with parts operationalizes active imagination, shadow integration, and individuation. The recognition of Self as organizing center parallels Jung’s Self archetype while making it more accessible.

Thousands of therapists trained in IFS practice worldwide. The approach has been adapted for couples, families, groups, and organizational settings. Applications extend beyond psychotherapy to coaching, education, conflict resolution, and personal development. Whether IFS represents enduring paradigm shift or transitional framework, Schwartz’s contribution has expanded therapeutic possibilities and given countless people language for their internal experience.

0 Comments