Who was Alan Watts? The Bridge Between East, West, and the Human Psyche

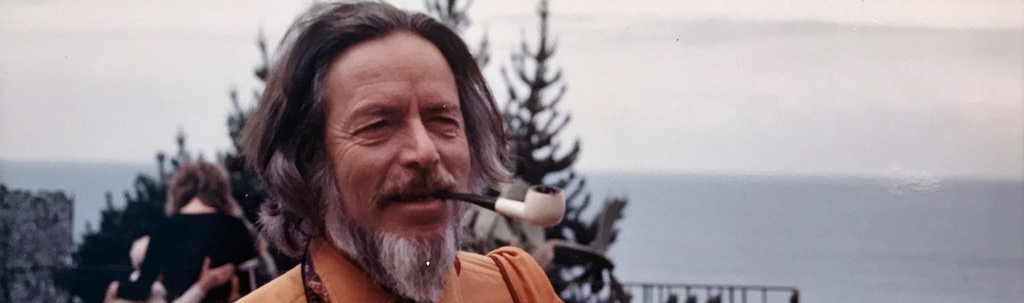

In the pantheon of 20th-century thought, few figures occupy a space as unique, controversial, and enduring as Alan Wilson Watts (1915–1973). He was not merely a philosopher, nor was he strictly a theologian or a psychologist. Rather, Watts was a “philosophical entertainer”—a self-described spiritual rascal who dedicated his life to translating the ineffable wisdom of the East into the pragmatic language of the West.

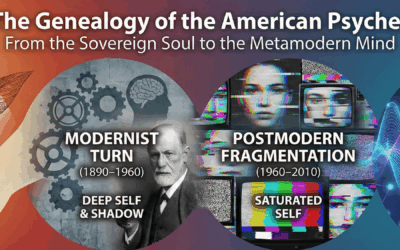

At a time when American culture was rigidly defined by consumerism, scientific materialism, and Judeo-Christian dogma, Watts arrived like a Zen koan: puzzling, delightful, and transformative. He introduced millions to Zen Buddhism, Taoism, and Vedanta, not as dry academic subjects, but as living, breathing paths to liberation. His work provided the intellectual scaffolding for the Counterculture movement of the 1960s, influencing everything from the human potential movement to the development of transpersonal psychology.

But who was the man behind the microphone? How did a British Episcopal priest become the voice of the psychedelic generation? And most importantly for us today, how do his ideas about the “illusion of the ego” intersect with modern depth psychology and the quest for individuation? This comprehensive exploration traces Watts’ journey from the English countryside to the hills of California, examining his profound impact on how we understand anxiety, identity, and the very nature of reality.

I. The Early Years: A Mystic in a Boarding School

Alan Watts was born on January 6, 1915, in Chislehurst, Kent, England. From the very beginning, he seemed destined to look beyond the confines of his culture. While his peers were reading adventure novels, a young Watts was captivated by the romanticized visions of the “Orient” found in the literature of his mother’s missionary family.

The Buddhist Lodge

By his teenage years, Watts had declared himself a Buddhist. In a remarkable turn of events for a schoolboy in 1930s England, he became the secretary of the London Buddhist Lodge. Here, he rubbed shoulders with scholars, mystics, and Theosophists, absorbing the teachings of the Mahayana tradition before he had even completed his formal schooling. This early immersion laid the groundwork for his lifelong project: identifying the “Perennial Philosophy” that underpins all spiritual traditions.

Unlike many Westerners who approach Buddhism as a system of ethics or a religion of renunciation, Watts was drawn to the aesthetic and experiential dimensions of Zen. He saw in it a remedy for the stifling repression of the British class system and the guilt-ridden morality of the Church. This tension—between the spontaneity of Zen and the rigidity of Western institutions—would define his career.

II. The Priest who Preached the Tao

Watts’ intellectual journey was far from linear. In 1938, seeking new horizons, he moved to the United States. In a move that surprised his Buddhist friends, he entered an Episcopal seminary and was ordained as a priest in 1945. For five years, he served as a chaplain at Northwestern University.

However, Watts was a Trojan Horse within the church. He attempted to harmonize Christian theology with Asian philosophy, arguing in works like Behold the Spirit that Christianity had lost its mystical core. He eventually left the priesthood in 1950, famously stating that he could not reconcile his growing understanding of Lao Tzu’s Taoism with the rigid doctrinal demands of the church. This departure marked the beginning of his “free-lance” philosophy career, where he would produce his most influential work.

III. Core Themes: The Wisdom of Insecurity

Watts was a prolific writer and speaker, but his vast body of work revolves around several central pillars that challenge the very foundation of the Western worldview.

1. The Illusion of the Skin-Encapsulated Ego

The central villain in Watts’ philosophy is the “Skin-Encapsulated Ego.” He argued that Westerners suffer from a hallucination: the belief that “I” am a separate entity residing behind the eyes, looking out at a foreign and hostile universe. Watts utilized the Hindu concept of Maya (illusion) to show that this separation is false.

He famously posited that we do not “come into” this world; we “come out of” it, like leaves from a tree. We are an aperture through which the universe observes itself. This radical reframing dissolves the anxiety of death and isolation, as the “self” that dies is revealed to be a fiction.

2. The Wisdom of Insecurity

In his 1951 masterpiece, The Wisdom of Insecurity, Watts tackled the Age of Anxiety. He argued that the desire for safety and certainty is the very cause of insecurity. By trying to grab hold of the moment, we kill it. He compared life to water: if you try to clutch it in your fist, you lose it; if you cup your hands gently, you can hold it. This aligns closely with the Taoist principle of Wu Wei (effortless action).

3. The Double-Bind of Morality

Watts was critical of the “guilt trip” inherent in Western morality. He pointed out the “Double Bind”—society commands us to be “good” and to love others, but love cannot be compelled. Trying to force oneself to be unselfish is the ultimate act of selfishness. He proposed that true morality arises spontaneously from the realization of our interconnectedness, not from the fear of punishment.

IV. Alan Watts and the Evolution of Psychotherapy

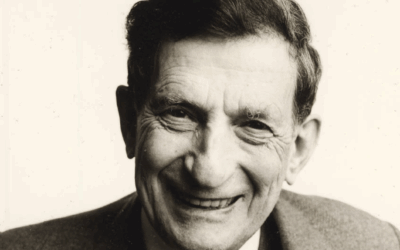

While Watts was a philosopher, his impact on the field of mental health was seismic. He was a close associate of figures like Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers, and his ideas helped catalyze the shift from the pathologizing model of Freud to the growth-oriented model of Humanistic Psychology.

Critique of the “Mental Hospital” Model

In Psychotherapy East and West (1961), Watts argued that the therapist functions as a modern-day guru or shaman. He suggested that neurosis is often a case of “mistaken identity”—the patient is sick because they believe the social fiction that they are a separate ego. The role of the therapist, therefore, is not to “fix” the patient’s mechanism, but to help them see through the social game they are playing.

[Image of Abraham Maslow hierarchy of needs]

Integration with Jungian Thought

Watts had a deep appreciation for Carl Jung, whom he met personally. Both men were interested in the integration of opposites and the wisdom of the unconscious. Watts’ concept of the “elemental self” mirrors Jung’s concept of the Self, while his critique of the social persona aligns with Jung’s work on the Persona and Shadow. Watts helped popularize the idea that the “Shadow” (the repressed aspects of self) must be integrated rather than destroyed.

The Psychedelic Renaissance

Watts was an early explorer of psychedelics, viewing substances like LSD and Psilocybin not as drugs of escape, but as tools for “chemical mysticism.” In The Joyous Cosmology, he articulated the psychedelic experience as a temporary dissolution of the ego boundaries, allowing the user to experience the non-dual reality directly. While he warned against relying on the “drug,” his work provided a philosophical framework for the use of altered states in healing that is currently being rediscovered in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

V. Influence on Culture and the Arts

Watts was the bridge between the Beat Generation and the Hippies. He drank with Jack Kerouac (who fictionalized him as “Arthur Whane” in The Dharma Bums) and debated with Timothy Leary. His voice became the soundtrack of a generation searching for meaning beyond material wealth.

The Voice of the Zeitgeist

Watts’ lectures were broadcast on KPFA radio in Berkeley, creating a following that transcended academia. His ability to explain complex concepts like Sunyata (voidness) using analogies from music, dance, and biology made him accessible to artists and musicians. Today, his voice is sampled in songs by artists ranging from logic to obscure lo-fi beats, proving his enduring relevance to the youth culture.

Environmental Ethics

Long before “sustainability” was a buzzword, Watts was preaching ecological consciousness. In Nature, Man and Woman, he argued that the Western view of nature as a mechanism to be dominated is a form of insanity. He posited that the environment is our “extended body.” If you destroy the external world, you destroy yourself. This deep ecology perspective is foundational to modern eco-psychology.

VI. The Shadow Side of the Guru

To produce a complete picture of Alan Watts, we must address the “rascal” element. Watts was not a saint, nor did he claim to be. He struggled with alcoholism and had a chaotic personal life, marked by three marriages and financial instability. He famously described himself as a “fake”—a spiritual entertainer rather than a holy man.

However, from a Jungian perspective, this flaw makes him more accessible, not less. He embodied the Trickster Archetype. He showed that one can possess profound wisdom and still be deeply human and flawed. He warned against the “guru trap,” urging his followers not to worship him but to look at where his finger was pointing.

VII. Legacy: Why Watts Matters Now

In the 21st century, we are more connected than ever, yet we suffer from an epidemic of loneliness and anxiety. We are drowning in information but starving for wisdom. Alan Watts offers a way out of the digital trap. He reminds us that life is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be experienced.

His synthesis of Eastern philosophy and Western psychology offers a toolkit for the modern soul. Whether we are grappling with existential anxiety, the fear of death, or the search for identity, Watts invites us to laugh at the cosmic joke: that we are the universe playing hide-and-seek with itself.

Mystics and Gurus

Bibliography

Primary Sources (Works by Alan Watts)

- Watts, Alan. (1951). The Wisdom of Insecurity: A Message for an Age of Anxiety. New York: Pantheon.

- Watts, Alan. (1957). The Way of Zen. New York: Pantheon.

- Watts, Alan. (1961). Psychotherapy East and West. New York: Pantheon.

- Watts, Alan. (1966). The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are. New York: Vintage.

Further Reading on Eastern Philosophy and Psychology

- Suzuki, D.T. (1964). An Introduction to Zen Buddhism. New York: Grove Press.

- Maslow, Abraham H. (1962). Toward a Psychology of Being. Princeton: Van Nostrand.

- Jung, C.G. (1958). Psychology and Religion: West and East. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Grof, Stanislav. (1985). Beyond the Brain: Birth, Death, and Transcendence in Psychotherapy. Albany: State University of New York Press.

0 Comments