The Metamodern Linguistic Turn

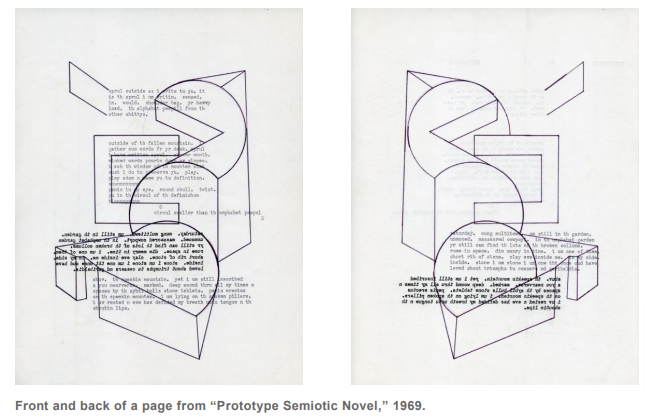

‘Whisper Piece’ by Bob Cobbing (1969)

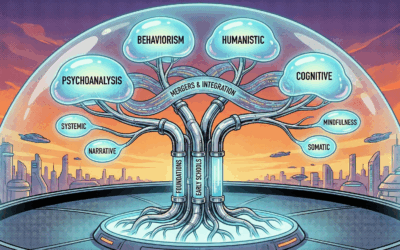

What is Metamodernism?

Metamodernism is an emerging cultural paradigm and sensibility that transcends the dichotomies of modernism and postmodernism. It seeks a synthesis of the universal aspirations and grand narratives of modernism with the relativism, irony and deconstruction of postmodernism.

As we progress further into the 21st century, it becomes increasingly clear that the cultural frameworks of the past are no longer adequate for making sense of our rapidly shifting world. The grand narratives and universal truths of modernism have broken down in the face of globalizing complexity and postmodern critique, yet the ironic detachment and deconstructive impulses of postmodernism offer little guidance for moving forward. We find ourselves in an ambivalent, transitional state, wavering between nostalgia for old certainties and a yearning for new meanings.

It is out of this tension that metamodernism inevitably emerges – not as a fixed ideology or aesthetic, but as a fluid sensibility that oscillates between modernist and postmodernist poles in an attempt to reconcile their oppositions. Metamodernism recognizes the need to recover a sense of direction and purpose, but understands this as a continual negotiation rather than a return to a stable foundation. It seeks to reconstruct meaning and hope in a more contingent, pluralistic way that acknowledges the inescapable flux and uncertainty of our time.

This metamodern turn represents a maturation of our cultural consciousness as we learn to inhabit the “both-and” rather than the “either-or,” synthesizing the insights of previous paradigms while pushing beyond their limitations. It is an ongoing, ever-evolving project that will define the 21st century as surely as modernism and postmodernism defined the 20th – a necessary grappling with the complexities we have inherited in search of new possibilities for co-existence and growth.

At its core, metamodernism is characterized by a resurgence of sincerity, hope, romanticism, affect, and the search for deeper meaning – but in a way that integrates postmodern skepticism rather than rejects it outright. Metamodernists acknowledge the constructedness of reality and identity, but still reach for transcendent truths through irony and pluralism. They pursue reconstruction as much as deconstruction.

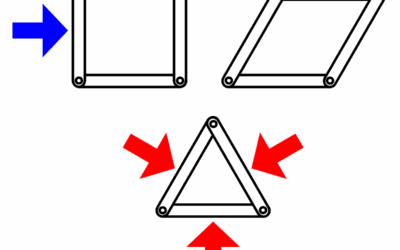

In the metamodern view, oscillation between opposing poles – between faith and doubt, sincerity and irony, construction and deconstruction, apathy and affect – moves us forward like a pendulum toward greater understanding. By contrast, modernists seek singular truth while postmodernists reject truth altogether in favor of endless relativism. Metamodernists aim to marry both perspectives into a “pragmatic idealism.”

The downside of historical thesis, antithesis, and synthesis of this cultural inevitable cycle is that we can get the worst of both worlds, and not just by accident. The relativistic lack of accountability of the post modern combined with the heroic and ego inflating grandiosity of the Nietzschean modernist myths and co-opting and misappropriation of the hero’s journey can lead to unconsciously messianic miscreants like Jordan Peterson or the collective projection of society onto figures like Donald Trump as a religious figure. If we are not careful and conscious about this oscillation, the tension between these poles can result in the projection of the modernist’s grand narratives on to strong men, and the ego inflating tendency of these mythic narratives leads us to cherry pick or disregard the science that stops medicine from becoming pseudo-science and cults groups.

Much of the schizotypal nature of modern culture and politics is due to this metamodern pull between the modernist meta-narrative and the post modern ability to deconstruct all narratives into agnosticism about any meaning or relevance. We are letting the most nefarious forces use this confusion to borrow the wrongness from both perspectives and install the most perverse incentive structures. Big words, I know. Let’s have a concrete example. When Donald Trump won in 2016 there were two debates taking place. One side said that there was a void of meaningful narrative and chose Trump as a mythic figure to fill the gap in the mythic religious function that society needs.

They conflated a 80’s real estate boomer tycoon into a god, an emperor and embedded him into American mythology of civics book propaganda. The other side of the aisle tried to counter this ineffectively by saying that Trump’s wealth was not really real, was just debt, or that he wasn’t that smart, or that the granular problems he identified got worse under his watch. American conservatives realized that the metamodern was hungry for a hero and instead of creating, embodying or waiting for someone that was deserving of the mantle they projected their emotional need for a hero onto Donald Trump. American liberals’ rebuffs of this projection were not effective.

American liberals continued to assure everyone that they would be rational stewards of the free market and respect the bureaucracy and proceduralism of government. Many people have lost faith that these rules and procedures result in the fulfillment of the values American liberals claim to represent; economic mobility, human rights, opportunities for educational advancement and access to affordable healthcare. Most voters in America have accepted that the free market and proceduralism of government not only do not result in these outcomes but are directly at odds with them. Democrats refused for three elections to offer a compelling vision of the future or to offer a grand material economic project that inspired anyone, as Obama’s push for universal healthcare had.

The belief that free market liberalism will result in anything that the left wing of America wants is a statistically speaking increasingly something that only older and wealthy Americans have the luxury of believing. Trying to pretend that the free market and interests of military contractors and billionaires somehow are not at odds with human rights and a better quality of life for most Americans is a bizarro project that the American electorate have rejected in larger and larger numbers each time it is offered. We have to weigh our need for a historical hero against our need for a rational logical take on planning a functional community. But no one will. It is easier for Democrats to say they lost nobly by the rules of literalism and proceduralism and ask us to respect hierarchies and traditions that no longer result in good outcomes. They won’t acknowledge how the world and the electorate actually work to be effective at getting anything done.

American liberals will not campaign on giving anyone anything they want economically or materially and instead play with spectacle, and insist they are the adults in the room for not being so gauche as Trump. Of course, healthcare, inflation, education, debt forgiveness, and cost of living in the country they are elected to run are not topics Democrats can touch. Instead they explain how noble it is to spend all of that money on another set of noble wars for empire that benefit the stock market. You cannot defeat the myths of the modern with the literalism of the post modern. You have to synthesize both.

Responsible metamodernism involves a deep awareness of global crises – climate change, income inequality, political instability. But where postmodernism responds with cynicism and despair, metamodernism strives for pragmatic hope that mobilizes toward solutions, however partial or imperfect. The metamodern outlook is one of informed naivety, pragmatic idealism, and a “romantic response to crisis.”

Crucially, metamodernism is also defined by the effects of digital technologies and network culture. Growing up immersed in the internet, metamodernists engage in a “hypernatural” fusion of the digital and physical, virtual and embodied, resulting in hybrid, fluid identities and modes of being. Social media nurtures a participatory ethos of constant creative production and a collapse between artist and audience.

Politically, metamodernists seek an alternative to both the neoliberal status quo and regressive fundamentalism in an age of anger and polarization. A metamodern politics pursues radical reforms through existing institutions based on empathy, care, and communal identity across difference. Key examples include Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, Podemos in Spain, and Extinction Rebellion.

In art and aesthetics, metamodernism manifests as a return to affect, authenticity, and representations of depth as opposed to the superficial irony of postmodernism. But it filters these restored conventions through digital remix culture, creating strange mash-ups of sincerity and irony, fiction and reality. Wes Anderson films, alt lit, and vaporwave exemplify a metamodern sensibility.

Philosophically, metamodernism draws on the work of Fredric Jameson, who called for a new “cognitive mapping” of our complex global systems; Mas Ud Zavarzadeh and Thelma J. Wils, who saw the emergence of a “metamodern condition;” and Vermeulen and Van den Akker who theorized the “structure of feeling” underlying the metamodern. More recently, Hanzi Freinacht has expanded metamodern theory into an ethical and political framework.

In summary, metamodernism represents an attempt to move beyond the conflicts of previous cultural paradigms into a new, more complex and nuanced sensibility adapted to 21st century realities. It reaches for reconstructed meanings while still holding space for mystery and ambiguity. By synthesizing the best of modernism and postmodernism, integrating intellect and emotion, ego and eco, scientific and spiritual worldviews, metamodernists hope to chart viable paths forward in an age of crisis.

The Emergence of Overlapping Modes of Meaning

How do you know that the color blue you see is the same color blue that I see? We both call it “blue”, but do we actually share the same subjective experience of that particular wavelength of light? This fundamental question about the nature of perception and meaning has long preoccupied philosophers, but in our contemporary moment, it has taken on a new urgency and complexity.

The metamodern age is marked by profound changes in our relationship to language and meaning-making. First, there is an emergent duality in metamodern communication, where literal technical meanings and mythic symbolic meanings overlap in the same linguistic signs and acts. This hybrid literal-figurative register reflects the metamodern drive to synthesize the rational objectivity of modernism with the relativist subjectivity of postmodernism.

We are living through a remarkable transformation in the nature of human communication, one that is reshaping the very foundations of language, culture, and politics as we know them. At the heart of this metamodern linguistic turn lie two interrelated phenomena: the emergence of a dual mode of discourse that oscillates between the literal and the symbolic, and the resurgence of an oral culture paradigm within the context of digital media.

In the first mode, we are using language more literally than ever before, with words serving as precise, technical labels for concrete realities. But simultaneously, in the second mode, we are using those same words as mythic signifiers, charged with symbolic and archetypal resonances. This strange dual register is not a “tower of Babel” situation of mutual unintelligibility, but rather a fluid shift between two frequencies of meaning. The result is a kind of metamodern code-switching, where the same phrase can operate as both factual description and symbolic incantation.

At the same time, the rise of social media is rewiring our relationship to the written word, infusing it with the participatory, improvisational, and ephemeral qualities of oral culture. Whereas the advent of print culture once imbued writing with a new sense of permanence and authority, digital platforms are recasting it as a real-time, fluid, and interactive medium. On Twitter or TikTok, language is less about recording timeless truths than about riffing on the memetic moment.

However, this is not a simple reversion to pre-literate orality. Rather, it is a hybrid condition in which the archival affordances of writing coexist with the experiential immediacy of speech. Even as social media collapses our sense of historical distance, we remain embedded in a culture of documentation and data. The result is a kind of multidimensional linguistic space, where the mythic and the literal, the eternal and the instantaneous, are woven together in complex patterns of significance.

To navigate this metamodern landscape, we will need to cultivate a new metalanguage – a mode of communication that can fluidly shift between and integrate the literal and the symbolic, the rational and the mythic. This language must be able to express timeless archetypes and memes while also conveying precise, data-driven realities. It must resonate in the embodied, affective register of orality and performativity, yet also retain the abstract, analytical clarity of textuality and literacy.

Most importantly, this metamodern language must enable mutual understanding and coordinated action across diverse worldviews and ways of knowing – scientific and spiritual, indigenous and cosmopolitan, artistic and activist. Only by developing a shared lingua franca for meaning-making can we hope to overcome the polarizing culture wars and existential crises that threaten our planetary future. The key lies in recognizing that we are all participating in a multidimensional space of significance, even when our localized experience of that space appears incommensurable.

So while I cannot be certain that my “blue” is the same as your “blue”, perhaps through the emergence of a metamodern metadiscourse, we may yet learn to see and speak a new spectrum of colors together. In the following analysis, we will explore the philosophical roots, technological conditions, political implications, and poetic potentials of this linguistic turn.

The Oral Rootsof Metamodernism: Participation, Performance, and Mythic Meaning

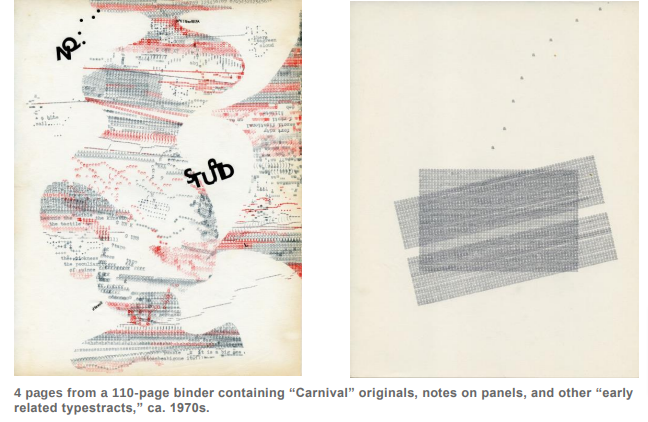

‘Beethoven Today’ by Bob Cobbing (1970)

To fully grasp the implications of the metamodern linguistic turn, we need to situate it within the deep history of human language and culture. In particular, we need to revisit the oral traditions that preceded the rise of literacy and print, and which continue to shape our modes of meaning-making in subtle but profound ways.

In oral cultures, language was not a static system of signs but a dynamic medium of performance and participation. Meaning emerged through the embodied, dialogical, and improvisational process of storytelling, where speaker and listener, poet and audience, were bound together in a shared space of co-creation. Think of Homer’s Odyssey where religion, culture, history, ethical dialogues and entertainment overlap in the same tale. Different modes of understanding unlock different parts of the tale as they are needed by the culture through oral participation and enhancement. The story was passed down orally from bard to bard. Each book corresponded to a letter of the Greek alphabet that crowds would yell at the bard to “vote” on which book the bard would tell that night when it was relevant to cultural, political or religious experience. The entire tale was almost never told all at once, yet was contained through societal memory.

This dynamic, participatory nature of oral culture is a key concept in the work of Jesuit philosopher and cultural historian Walter J. Ong. In his seminal book “Orality and Literacy,” Ong argues that the shift from orality to literacy fundamentally restructured human consciousness and social organization. Whereas oral cultures were characterized by a sense of immediacy, communality, and mythic identification, literate cultures increasingly prioritized abstraction, individuation, and rational analysis.

With the advent of writing, and especially with the spread of print culture, the performative and participatory dimension of language was progressively marginalized. The fixed, abstract, and decontextualized nature of the written word fostered a new conception of meaning as something objective, universal, and eternal. The rise of modern science and philosophy, with their emphasis on logical argumentation and empirical evidence, further reinforced this view of language as a neutral instrument of reason.

But as we’ve seen, the digital age has in many ways brought us full circle, back to an era of “secondary orality” that fuses premodern mythic participation with postmodern irony and virtuality. Memes are the perfect embodiment of this fusion – visual, participatory, and performative like oral culture; decontextualized and endlessly remixable like print culture; and shot through with postmodern irony, absurdism, and meta-reference.

Yet as Ong and other media theorists have argued, the dominance of print culture was always a temporary and contingent phenomenon. Even as literacy spread and books proliferated, oral and visual modes of communication continued to thrive in various forms, from folk tales and ballads to theater and cinema. And with the emergence of electronic media in the 20th century, we have seen a gradual rebalancing of the sensory and cognitive biases of the literate mind.

Radio, television, and now the internet have all contributed to what Ong called a new kind of “secondary orality,” one that combines the participatory and immersive qualities of premodern oral culture with the technological affordances of modern media. Digital platforms, in particular, have radically expanded the possibilities for ordinary people to create, share, and remix content, blurring the lines between producer and consumer, author and audience.

In Ong’s view, this resurgence of orality is not a regression to a pre-literate state, but rather a dialectical synthesis of oral and literate modes of consciousness. Secondary orality retains the analytical and self-reflective capacities of literacy, but reintegrates them with the empathetic, holistic, and communal sensibilities of orality. It is a way of thinking and communicating that is at once more abstract and more concrete, more rational and more mythic, than either pure orality or pure literacy.

This hybrid oral-literate consciousness is precisely what we see emerging in the metamodern era, as digital natives seamlessly navigate between the literal and the symbolic, the factual and the fictional, the sincere and the ironic. The memetic, remix-driven culture of social media is a prime example of this new linguistic mode, where timeless archetypes and cutting-edge data interweave in endlessly creative recombinations.

At the same time, the participatory ethos of digital culture is also reviving the performative and ritualistic dimensions of language that were central to oral traditions. From viral TikTok challenges to Twitter hashtag games, online communication often takes on a playful, improvisational quality that echoes the collaborative storytelling of ancient bards and griots. Even as we type alone at our screens, we are engaged in a kind of virtual campfire circle, co-creating shared narratives and mythologies in real-time.

Of course, this new orality is not without its risks and challenges. The speed and scale of digital communication can lead to the spread of misinformation, the reinforcement of echo chambers, and the flattening of nuance and context. The algorithmic logic of social media platforms can privilege sensationalism and outrage over thoughtful deliberation and empathy. And the constant pressure to perform and curate our online identities can breed a kind of self-consciousness and inauthenticity that undermines genuine connection.

But at its best, the metamodern synthesis of orality and literacy offers a powerful toolkit for navigating the complexities of the 21st century. By tapping into the ancient wellsprings of mythic meaning-making, while also leveraging the analytical and empathetic capacities of the literate mind, we can forge new forms of understanding and cooperation across differences. We can use the participatory power of digital media to amplify marginalized voices, challenge dominant narratives, and mobilize collective action for social change.

Ultimately, the metamodern linguistic turn invites us to reintegrate the embodied, affective, and relational dimensions of language that have been suppressed by the print-centric paradigm of modernity. It reminds us that meaning is not a static property of words on a page, but a dynamic, co-creative process that emerges between speakers and listeners, writers and readers, humans and machines. By embracing this more holistic and dialogical conception of language, we can begin to heal the splits and polarizations that divide us, and to weave a new story for a world in crisis.

As Ong himself put it, “Orality is not an ideal, and never was. Literacy opens possibilities to the word and to human existence unimaginable without writing. This awareness, however, need not blind us to the distinctiveness of orality or the significance of its persistence in the midst of a literate culture. Nor should it reduce our sense of the critical importance to use of writing in restructuring the human lifeworld to bring it out of the world of sound into the world of sight.”

In the metamodern age, we have the opportunity to bring together the worlds of sound and sight, orality and literacy, myth and reason, in a new synthesis that honors the full spectrum of human experience. By reclaiming the oral roots of our linguistic heritage, we can tap into new sources of creativity, empathy, and wisdom for a time between stories. The future of meaning belongs to those who can speak and listen, write and read, dream and analyze, with equal fluency and care.

The Politics of Metamodern Meaning: Oscillating Between Irony and Sincerity

In many ways, the rise of digital media has brought about a resurgence of these oral and mythic modes of meaning-making. Now crowds want to control the attention of the algorithm, not the bard. Social media platforms like Twitter and TikTok are characterized by a highly participatory and performative style of communication, one that privileges affective resonance over factual accuracy, collective creativity over individual authorship. The rapid circulation of memes and viral content has given rise to new forms of digital folklore, where the boundaries between the real and the fictional, the sincere and the ironic, are constantly blurred.

In this sense, the metamodern linguistic turn can be seen as a kind of return of the repressed, a re-emergence of the oral and mythic dimensions of language that were suppressed by the rationalist paradigm of modernity. But it is not a simple regression to a pre-modern state of enchantment. Rather, it is a new synthesis of the literate and the oral, the rational and the mythic, the individual and the collective. It is a language that is both more embodied and more abstract, more immediate and more mediated, than anything that has come before.But in the metamodern era, we are seeing a new kind of synthesis and hybridization of these different modes. Digital media has given rise to a new orality, a participatory and performative style of communication that draws on the rhythms and cadences of spoken language. At the same time, it has also amplified the reach and durability of written texts, creating a vast archive of cultural memory that can be easily searched and shared.

This is unprecedented. In the past we have had oral culture, and then later a written culture, but never have we had both modes of language sharing the linguistic space at the same time. We have had people speak different languages with different words, but never different languages with the same words. We feel both hyper connected and hyper isolated. What we say is seen and examined by more people than we can comprehend but we feel less understood and less seen than has ever been recorded. This explains the political and media paradox in the current public squares and political forums. People speak two modes of language at once with the same language and sometimes forget the mode of language that they are even using. Many people prefer one sphere of communication but are now forced to share space with both, critically and artistically.

Art and argument are subjected to the scrutiny of post modern deconstruction and the demand for the heroic narratives of modernism at the same time. Whenever we lose one mode of argument online trolls can retreat into the comfort that no one understands the mode of language they are using. There is no way to win or lose such a debate on such shifting ground and most people do what is easiest and never reconcile this tension.

Often we feel secretly more similar to our enemies than our allies heightening the confusion, making us hate them all the more. They represent a mode of speech we have not mastered so we retreat back into our preferred mode of language where they cannot catch us, but within the same words. Each mode of language needs its opposite to reinforce its perspective as correct and so social media has left us spending more time reading and obsessing about people that we disagree with than people that we like and could build community with.

This linguistic instability allows bad faith actors to retreat into ambiguity and avoid accountability is troubling but rings true. Language is being subjected to contradictory pressures – to fragment and dissolve meaning on the one hand, and to express timeless truths and grand visions on the other. This can lead to profound misunderstandings and conflicts, as people talk past each other without realizing they are inhabiting different linguistic universes.

In obsessively tracking and reacting to the language of our opponents, we end up mirroring them in ways that can be uncomfortable to acknowledge. The oppositional energy that animates so much online debate can end up overshadowing the more constructive project of articulating shared values and visions.

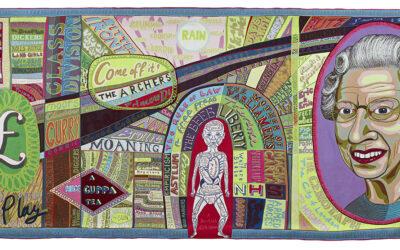

‘Barcelona Love Letters’ by Keira Rathbone (2012)

This new metamodern language is not just a neutral medium of communication, but a contested terrain of political and cultural struggle. In an age of post-truth politics and information warfare, the ability to control the narrative, to shape the symbolic landscape of collective meaning-making, has become a crucial source of power.

On one level, the metamodern linguistic turn has opened up new possibilities for grassroots activism and resistance. Movements like Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter have used social media to challenge dominant discourses and mobilize collective action, often in ways that blend sincere moral outrage with ironic meme-making and hashtag wordplay. The participatory and improvisational ethos of digital culture has allowed for the rapid emergence of new forms of political subjectivity and solidarity, from the “networked individualism” of the Arab Spring to the “weird global” aesthetics of vaporwave and accelerationism.

At the same time, the metamodern linguistic landscape has also given rise to new forms of manipulation and demagoguery. Figures like Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro have exploited the ambiguities of irony and sincerity, fact and fiction, to sow confusion and division, often with the help of coordinated disinformation campaigns and algorithmic amplification. The same memetic strategies that have been used to challenge power can also be used to entrench it, creating a kind of hall of mirrors where truth and falsehood become increasingly difficult to disentangle.

In this context, the ability to navigate the shifting registers of literalism and symbolism, sincerity and irony, has become a key political skill. Movements and leaders must be able to speak in multiple codes at once, appealing to both the rational interests and the mythic imaginations of their audiences. They must be able to use language not just to describe reality but to create it, to conjure up new forms of collective identity and agency in the face of social fragmentation and existential threat.

This is not to say that the politics of metamodernism is a purely relativistic or nihilistic affair, where all meanings are equally valid and all truths are up for grabs. On the contrary, the metamodern sensibility is characterized by a renewed commitment to the idea of universal values and objective realities, even as it recognizes the inescapable plurality of perspectives and experiences. It is a politics that seeks to ground itself in the concrete struggles and aspirations of ordinary people, while also reaching for the transcendent horizons of a more just and beautiful world.

The first step in navigating the metamodern linguistic landscape is to cultivate a perspective that allows us to step outside of each mode of language, to see their respective purposes and not overly identify with any single one. By maintaining a witnessing awareness, we can use these different linguistic modes selectively and skillfully, as tools for specific ends rather than as totalizing worldviews that subsume our identity.

This requires a kind of metamodern mindfulness, a capacity to observe our own participation in the meaning-making process without being entirely swept away by it. We must learn to recognize when we are speaking in mythic or memetic registers, when we are using language for poetic or political purposes, and to discern the appropriate context and limits of each mode. At the same time, we need to honor the unique gifts and insights that each linguistic realm offers, and to explore their potential synergies and harmonies.

By cultivating this “witness consciousness,” we paradoxically become more engaged and empowered as meaning-makers. We are no longer merely passive consumers of cultural narratives, but active weavers of the stories that shape our world. We can more intentionally choose which myths to enact, which memes to spread, which poetic possibilities to manifest. Of course, this is a continual practice, not a final achievement – we are always already immersed in language, and can never entirely escape its influence. But by bringing more awareness to our own linguistic constructions, we open up new spaces of freedom and creativity within them.

The Poetics of Metamodern Meaning: Remixing the Mythic and the Material

The politics of metamodern meaning, however, cannot be separated from its poetics. The way we use language to create and navigate the world is always already shaped by the aesthetic and affective dimensions of communication, from the rhythms and cadences of speech to the visual and auditory textures of multimedia.

In the metamodern era, this poetic dimension of language has taken on a new urgency and intensity. The proliferation of digital media has given rise to a vast array of new forms and genres, from memes and GIFs to vlogs and TikToks, each with their own unique styles and sensibilities. At the same time, the global reach and instantaneous circulation of online content has accelerated the process of cultural hybridization and remix, blurring the boundaries between high art and popular entertainment, Western and non-Western traditions.

In this context, the role of the poet or artist is no longer to create original works of individual genius, but to curate and recontextualize the fragments of a shared cultural archive. The metamodern creator is less a romantic visionary than a skillful bricoleur, stitching together the mythic and the material, the timeless and the timely, into new patterns of meaning and affect.

This remix aesthetic is not just a matter of superficial pastiche or ironic detachment. At its best, it represents a sincere attempt to grapple with the complexities and contradictions of the metamodern condition, to find new ways of expressing the inexpressible and representing the unrepresentable. By juxtaposing and recombining seemingly disparate elements – ancient archetypes and cutting-edge technologies, personal memories and collective histories, sacred rituals and profane memes – metamodern art seeks to create a new mythology for a world in flux.

One of the key features of this metamodern poetics is its emphasis on materiality and embodiment. In contrast to the disembodied abstractions of postmodern theory, metamodern creators are increasingly attuned to the sensory and affective dimensions of language, from the tactile pleasures of handwriting to the visceral impact of spoken word performance. They recognize that meaning is not just a matter of semantic content, but of the physical and emotional resonances that words and images evoke in the body and the brain.

At the same time, metamodern poetics is also deeply engaged with the mythic and archetypal dimensions of human experience. From the resurgence of fantasy and science fiction genres to the proliferation of conspiracy theories and alternate reality games, metamodern culture is marked by a renewed fascination with the primal stories and symbols that have shaped our collective imagination for millennia. But rather than simply repeating or rejecting these myths, metamodern creators seek to remix and reinterpret them for a new era, finding fresh relevance and resonance in the timeless tales of heroes and tricksters, gods and monsters.

In this way, the poetics of metamodern meaning offers a kind of antidote to the flattening and fragmentation of postmodern culture. By reconnecting us to the deep structures of narrative and metaphor, by re-enchanting the world with a sense of mystery and wonder, it opens up new spaces of imagination and possibility. At the same time, by insisting on the materiality and specificity of language, by grounding itself in the concrete realities of embodied experience, it resists the temptations of escapism and mystification.

Pitman’s Typewriter Manual (1893)

The Future of Meaning in a Metamodern Age

‘Textum 2’ by Miroljub Todorovic (1973)

One of the key challenges of the metamodern linguistic turn is the way it destabilizes our very notions of truth and reality. In a world where the same words and symbols can mean radically different things to different people, where the boundaries between fact and fiction are constantly blurred, it becomes increasingly difficult to anchor our beliefs and actions in a shared sense of what is real and what is not. We risk falling into a kind of cognitive dissonance or existential vertigo, where everything seems equally true and false, meaningful and meaningless.

At the same time, the metamodern condition also threatens to erode our capacity for critical thinking and rational discourse. When every claim can be countered with an equal and opposite claim, when every argument can be dismissed as just another story or perspective, we risk sinking into a kind of nihilistic relativism or cynical detachment. We lose the ability to distinguish between valid and invalid forms of reasoning, between genuine insight and mere opinion.

To navigate these challenges, we need to cultivate a new kind of literacy and discernment. We need to learn how to read between the lines of metamodern discourse, to discern the hidden agendas and assumptions behind different forms of expression. Miles Davis said that Jazz music was about “the notes you don’t play” and we need to learn that to hear the truth in what people are not saying. When politicians are talking about things that they feel and believe, younger generations have become comfortable enough with digital media to begin to ask what they are willing to do to actually create change.

If you are not willing to say what you want to accomplish and how you will accomplish it younger people increasingly view you as incompetent, dishonest or controlled by capitalist forces. This style of dialogue was fine for the wholesome fireside chats of the radio days but in the days of digital media it makes it clear you are lying. Those who grew up with a heightened tolerance for the dual modes of internet communication want politicians that lay out plans for concrete change in a material reality, not navel gazing and pontification on the complexity of big ideas.

We need to rapidly develop a more sophisticated understanding of the ways that language and media shape our perceptions and beliefs, and to use that understanding to resist manipulation and misinformation. Many of the people left behind and deluded by digital politics are simply trying to engage the current discourse with an older paradigm that is failing.

At the same time, we also need to embrace a more expansive and inclusive vision of truth and knowledge. Rather than clinging to narrow, binary notions of fact vs. fiction, objectivity vs. subjectivity, we need to recognize the irreducible complexity and multiplicity of human experience. We need to find ways of integrating different forms of meaning-making – from the scientific to the artistic, from the rational to the intuitive – into a more holistic and dynamic understanding of reality.

At the same time we need to invent new forms of ideological accountability that include subjectivity and not the hall monitor fact checking of the old order. Bad actors should be corralled and shamed even when they tell ideological lies with subjective truths. In other words we should also hold people accountable for what the do not say, in the metamodern those omissions are also statements of belief. We should develop modes to identify the hidden assumptions and agendas behind different forms of expression.

What is truly unprecedented about the metamodern linguistic turn is the way it brings together two modes of communication and meaning-making that have historically been seen as separate and even opposed – the oral and the written, the mythic and the rational, the timeless and the timely. In the past, the rise of literacy and print culture was often associated with a kind of cultural imperialism, a devaluing of oral traditions and ways of knowing. Colonial powers judged and suppressed the rich storytelling heritage of indigenous peoples, imposing Western notions of history and progress as universal standards.

This is not to say that the metamodern linguistic turn is a smooth or easy process. On the contrary, it is often marked by tension, contradiction, and conflict. The very fact that we are using language in such different and even incompatible ways can lead to a sense of cognitive dissonance and communicative breakdown. We may find ourselves talking past each other, using the same words but meaning entirely different things.

But it is precisely in this tension and ambiguity that the transformative potential of metamodernism lies. By forcing us to confront the limits and contradictions of our own meaning-making systems, it opens up new spaces of creativity and possibility. It invites us to step outside of our comfort zones, to experiment with new forms of expression and understanding.

In this sense, the metamodern linguistic turn is not just about language, but about the very nature of reality itself. It is a recognition that the world is not a fixed or static thing, but a fluid and dynamic process of co-creation, in which we are all active participants. It is an invitation to embrace the mystery and complexity of existence, to find meaning and beauty in the midst of uncertainty and change.

Of course, this is easier said than done. The metamodern condition can be deeply unsettling and disorienting, as old certainties crumble and new possibilities emerge. It requires a kind of existential courage and resilience, a willingness to let go of our attachment to fixed identities and rigid ideologies.

The metamodern linguistic turn is a call to that courage, a summons to that creativity. We must learn to sit with both uncertainty and tension with rapt attention in a n age where the immediacy of digital life has made many adults in to children that can do none of these three things. The willing must step into the unknown, to embrace the mystery and the wonder of this future synthesis

The Synthetic Synthesis of the Metamodern

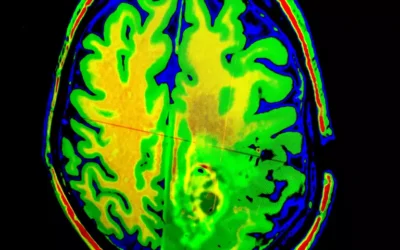

When Peak Neuroscience joined forces with Taproot Therapy Collective to offer quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG) brain mapping, I couldn’t resist asking the clinical psychologist who runs the clinic numerous silly questions about the technology they use to help brains heal. One question I had was about the fascinating property of brains to entrain to and mimic external frequencies and thought patterns. This neuroplasticity principle underlies the neurostimulation and neuromodulation treatments we provide at my clinic.

I asked the psychologist: “What would happen if you could somehow duct tape five or six living brains together while keeping them intact and healthy?” He theorized that the brains would likely start to synchronize their frequencies as they recognized each other’s repetitive patterns. They would then potentially reorganize and build new neural networks among themselves to form a more efficient collective organism. While this scenario is obviously speculative science fiction, it serves as an intriguing metaphor for what we are witnessing with the emergence of metamodernism in society. The individual “brains” or minds would each gravitate towards specialized roles within the unified whole and develop a new interdependent sense of individuality based on distributed functions that previously operated autonomously. This is similar to what happens when part of a brain is removed in a hemisphirectomy in children. Other parts of the brain will learn to compensate for and adopt the functions of the removed part as the child grows.

One cautiously optimistic interpretation of humanity’s future is that all the minds comprising society are now fusing into a singular larger being that is both terrifying and liberating, and perhaps inevitable. This great synthesizing occurs as the accelerating speed of communication and proliferating modes of interconnection entwine us into a vastly complex, interdependent neural network. It is simultaneously composed of individuals and made up of inseparable, interlinked parts.

This state of being both hyper-individualized and hyper-connected is a novel phenomenon unparalleled in human history. It compels us to radically reimagine our notions of identity and social interaction. In essence, we must learn how to integrate the seemingly paradoxical polarities of self and other – to identify both as the familiar parts of ourselves and as the greater super-organism beyond ourselves that we are a part of.As society functions like one connected brain it has more potential but also more potential for more horrifying disorders and neuroses than one brain alone was ever capable of. These distinctions and connections must become more fluid, while still allowing us to retain our individuality within the collective.

But this process of cognitive extension is not without its dangers and distortions. Just as the imperial powers of old sought to colonize and exploit the lands and peoples they encountered, so too do our own minds seek to colonize and exploit the neural networks we come into contact with, both human and artificial. We mistake the patterns and algorithms of Facebook or Twitter for extensions of our own consciousness, and in doing so, we risk losing sight of the ways in which they are shaping us in turn.

Minds that have awoken to this digital awareness earlier than others have felt, conciouslly or unconciously, the potential of these unmapped neural territories on the internet. Many of the negative aspects of the digital viral culture we see now are bad actors attempt to probe for and colonize weak nodes on the network. They search for weak structures and untapped energy in the networked zeitgeist to harness and redirect its potential energy for their own ends.

This is a troubling dynamic we see playing out in the attempts of nation states to colonize these new spaces. The metamodern landscape is rife with examples of governments and corporations seeking to manipulate and control the flow of information, to use the power of digital networks to spread propaganda and misinformation, to colonize the minds of their citizens and consumers. From the “Great Firewall” of China to the “troll farms” of Russia to the targeted advertising of Silicon Valley, we are witnessing a new scramble for cognitive territory, a battle for the attention and allegiance of our networked brains.

At the same time, we are also seeing new forms of resistance and revolt emerging from within these digital matrices. Just as the native peoples of the Americas and Africa found ways to resist and subvert the colonial project through acts of cultural and spiritual syncretism, so too are marginalized and oppressed groups finding ways to hack and remix the tools of their oppressors, to use the power of memes and hashtags to create new spaces of autonomy and solidarity.

Hope for the Metamodern Future

One illuminating parallel for how we might achieve this is the recurring impact that dominant empires and religious conversions have had on indigenous populations throughout history. These societies that were forcefully integrated into empires mimic the economic realities of late capitalism. The dialectical tension between assimilation and self-determination in the face of hegemonic forces is a central theme in much Japanese anime, such as the classic series Neon Genesis Evangelion. It explores the perennial existential question of whether ego identities should merge into a transcendent unitive awareness or remain separate and bear the profound isolation and suffering that often accompanies individual existence. These dilemmas of identity and otherness trace back to primordial myths like the Garden of Eden and have been wrestled with for millennia.

Japan serves as a compelling case study for these dynamics, having undergone multiple cultural and spiritual transitions. It transitioned from an imperial colonial power to a country assimilated into the Western capitalist world order. Its indigenous Shinto religion was supplanted by market-driven values and ideologies imposed by the United States government as part of a concerted propaganda campaign following World War II. The Japanese people have viscerally grappled with these polarities of individual and collective identity before, albeit in different forms. And yet Japan became an integrated part of these forces while still an individuated and distinct cultural and artistic identity. Now parts of its art and production have come to imperialize the culture of the West. There are many other examples like this in history where unity and individuality struck a cultural and political balance.

So while metamodernism confronts us with an unprecedented leap in human experience, we can still draw instructive insights by studying past iterations of this interplay between integration and differentiation, individual and collective, self and society. The keys to adapting in the future may therefore lie hidden in plain sight in our own histories. By reflecting on these timeless mythic themes and archetypes – whether through Joseph Campbell’s model of the Hero’s Journey or Carl Jung’s concepts of the collective unconscious and individuation – we may discover renewed solutions to our current meta-crisis of meaning. Our guiding lights forward are the ancient stories we carry within.

In the search for mythopoetic alternatives do the disembodied digital predicament, we can look to the profound wisdom of indigenous cultures like the Aboriginal Australians and their concept of the Dreamtime. The Dreamtime is a sacred era in which ancestral totemic spirits sang the world into existence. But it is not just a distant past – it is an eternal realm that interpenetrates ordinary reality and can be accessed through ritual, art, and states of consciousness.

In the Dreamtime stories, individual beings are not separate, isolated entities but rather nodes in a vast web of kinship that encompasses the entire cosmos. Each person has multiple overlapping identities based on their ancestral lineages, totemic affiliations, and the particular Songlines or Dreaming tracks that crisscross their territory. The boundaries between self and other, human and nature, matter and spirit are fluid and permeable.

This indigenous worldview offers a powerful framework for navigating the metamodern situation in which we find ourselves. Just as the Dreaming spirits are both timeless archetypes and localized, embodied expressions, each of us contains the universality of the collective unconscious while manifesting a unique individual consciousness. We are simultaneously dreaming and being dreamed by greater powers.

The Dreamtime also teaches us that crises and disruptions are initiatory thresholds for transformation and renewal, not apocalyptic end points as they are often portrayed in modern narratives. The arid Australian landscape is prone to wildfires that destroy entire bioregions, but the Aboriginal people understand that these conflagrations are a necessary part of the regenerative cycle of life. They clear away the old growth to make space for new sprouts to emerge from the ashes, and reset the ecological balance.

In the same way, the metamodern mind may need to undergo a psychic “burnoff” of outdated belief systems, identities, and social structures in order to unleash the latent creative potential within. This process is not comfortable or painless by any means, but it is an essential ordeal for our collective maturation. We must endure the tension of cognitive dissonance before we can arrive at a new coherence.

The mythic role of the shaman in indigenous societies also sheds light on our metamodern undertaking. The shaman is a liminal figure who traverses between the ordinary and extraordinary, the human and more-than-human realms. By ingesting sacred plants, entering trance states, or engaging in extreme ritual ordeals, the shaman temporarily fragments their mundane ego so that it can be reconstituted in a more integrated, multidimensional form. They return to the community bearing healing insights, creative visions, and a renewed sense of reciprocal balance.

We are all called to be shamans in this time between stories, to make the hazardous descent into the depths of our individual and collective psyche, to retrieve the soul-fragments we have lost, and to re-enchant the world with mythopoetic meaning. This does not mean a regression to pre-modern superstitions, but rather a quantum leap into a new synthesis of archaic and modern, intuitive and rational, spiritual and scientific ways of knowing.

Read another article on this topic.

0 Comments