The Psychohistory of American Warfare From Sensibility to Dissociation

The history of the United States is frequently told through the lens of political maneuvering and economic expansion but there exists a shadow history that runs beneath the dates and treaties. This is the history of the American psyche under the immense pressure of organized violence. To understand the true nature of the nation and its people one must look beyond the battlefield strategies and into the unconscious forces that have driven the country to war time and again. This exploration requires us to merge the discipline of history with the insights of depth psychology a field known as psychohistory. It is an approach that posits that the collective behavior of nations is not merely the result of rational calculation but is often a projection of unresolved childhood traumas societal repressions and the desperate search for meaning in a chaotic world. The nation like the individual possesses a tripartite psyche. The Ego represents the rational government and its stated ideals. The Id contains the repressed violence and primal rage of the populace. The Shadow holds the unrecognized and despised aspects of the national character that are projected onto the enemy. From the hysterical sensibility of the founding fathers to the dissociated remote warfare of the drone age the evolution of American warfare offers a profound case study in the human mind’s capacity for destruction and its resilience in the face of trauma.

The American Revolution as Collective Patricide and the Primal Id

The birth of the United States was a traumatic separation from the fatherland and this psychological reality permeated the rhetoric and experience of the Revolutionary War. The conflict was not simply a dispute over taxation it was a collective act of patricide that required a massive restructuring of the colonial identity. The culture of sensibility played a crucial role in this transformation allowing the colonists to rationalize their Id driven rage against the King into a medical and moral necessity. In the late eighteenth century the prevailing medical and cultural theories held that the nervous system was the seat of moral and emotional life. A person of high sensibility was one whose nerves were attuned to the slightest moral disturbance. This medical philosophy imported from the Scottish Enlightenment reframed political tyranny as a physical assault on the nervous system. The colonists viewed themselves as possessing a refined sensibility that was being assaulted by the unfeeling measures of the British crown. The tea boycott was medicalized as well as politicized. Tea was portrayed not just as a taxable commodity but as a substance that enervated the colonial constitution just as British policy enervated their liberties. The rejection of tea was a rejection of a toxic foreign influence that threatened the virility and nervous stability of the emerging American character. This weaponization of feeling allowed the colonists to frame their rebellion as a biological necessity a defense of their very nerves against an insensitive parent masking the primal violence of the revolt behind a veneer of physiological fragility.

Domestic Disruption and the Psychic Toll on Early American Families

However the trauma of the war itself was far more brutal than the high minded rhetoric of sensibility would suggest. The domestic sphere became a locus of intense psychological disruption where the Ego ideals of the new republic clashed with the chaotic reality of civil war. The psychological impact of the Revolution manifested in unexpected ways. The quartering of British soldiers in private homes disrupted the gendered order of the household and stripped American men of their domestic authority. For a man of that era his identity was deeply rooted in his ability to protect and control his household. The presence of enemy soldiers who did not respect this authority was a form of psychological castration that fueled the rage of the rebellion. We see the specific toll of this trauma in the lives of individuals like Azel Woodworth who was only fifteen years old when he served at the Battle of Groton Heights in 1781. He was struck by a musket ball in the neck an injury that rendered him insensible for a time. But the physical wound was only the beginning. His memoirs describe a deranged state where his mental faculties would retire for twenty four hours at a time. He suffered from significant intellectual incapacity that waxed and waned preventing him from learning a trade or maintaining a livelihood. The newly formed federal government struggled to categorize and pension such invalid soldiers. Woodworth became a wandering person dependent on charity a living testament to the fact that the psychological cost of independence was borne by the broken minds of its children. Recent scholarship into the violence of the American Revolution which included the psychological and physical torture of loyalists and the rape of colonial women challenges the sanitized view of a gentleman’s war. It was a conflict marked by intimate violence that left a deep scar on the American psyche manifesting in a post war struggle to define the new nation’s character amidst the debris of its violent birth.

Identity Crisis in the War of 1812 and the Rise of Manifest Destiny

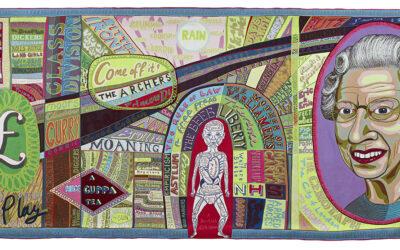

If the Revolution was the adolescent breaking away from the parent the War of 1812 was the young adult’s crisis of competency. The United States having achieved independence found itself suffering from a profound national anxiety. The continued impressment of American sailors by the British Royal Navy was not just a violation of sovereignty it was a psychological negation of American identity. It suggested that an American was not truly free but was still a subject of the British crown. This triggered an identity crisis within a nation influenced by European standards even as it tried to reject them. The war was necessary not for territory but for the psychic integration of the nation’s Ego. It was a war to prove that the separation was real. The burning of Washington and the defense of Baltimore became psychodramas where the nation faced the threat of annihilation and survived reinforcing a fragile collective ego. By the mid 19th century the American psyche had shifted from defensive anxiety to grandiose narcissism. The doctrine of Manifest Destiny rationalized aggression as divine will. This allowed the nation to bypass the moral guilt of conquest. In this psychological framework Mexico was projected as the weak chaotic and imbecile other that needed to be absorbed by the vigorous and masculine Anglo Saxon spirit. The war was a projection of the nation’s own shadow the desire for domination disguised as benevolence. The seizing of half of Mexico’s territory was a narcissistic injury inflicted on a neighbor to feed the voracious ego of a growing empire. Modern historiography reveals this not as a predetermined march of progress but as a morally contentious war that deeply divided the American conscience and set the stage for the internal fracturing that was to come.

The Civil War as the Integration of the National Shadow

The Civil War was the moment when the American psyche split in two and turned upon itself. Historians have long debated the causes but the psychological root lay in the trauma of slavery and the immense burden of guilt and projection it placed upon the nation. The slaveholding South lived in a state of constant psychological siege projecting its own fears of dependency and rebellion onto the enslaved population. This projection created a paranoid style of politics that viewed any challenge to the institution of slavery as an existential threat. The North meanwhile often projected its own economic ruthlessness onto the South creating a dynamic where each side carried the Shadow of the other. The war itself unleashed a wave of psychological devastation that the medical science of the time was ill equipped to handle. Doctors spoke of nostalgia and soldier’s heart to describe the condition of men who had been shattered by the industrial slaughter of battles like Antietam and Gettysburg. These terms described a condition of profound melancholy physical wasting and autonomic dysregulation that we would today recognize as post traumatic stress. The sheer scale of the death toll created a culture of mourning that permeated every aspect of American life. The transcendentalist dream of an innocent agrarian republic was buried in the trenches of Petersburg. For African American soldiers the war was a fight for psychological as well as physical emancipation. They carried the mental trauma of slavery and racialized violence into battle. The threat of execution or re enslavement if captured added a layer of psychological terror to their combat experience. Pension records from the era show numerous cases of insanity among black veterans reflecting the double burden of combat trauma and the systemic oppression they faced both before and after the war.

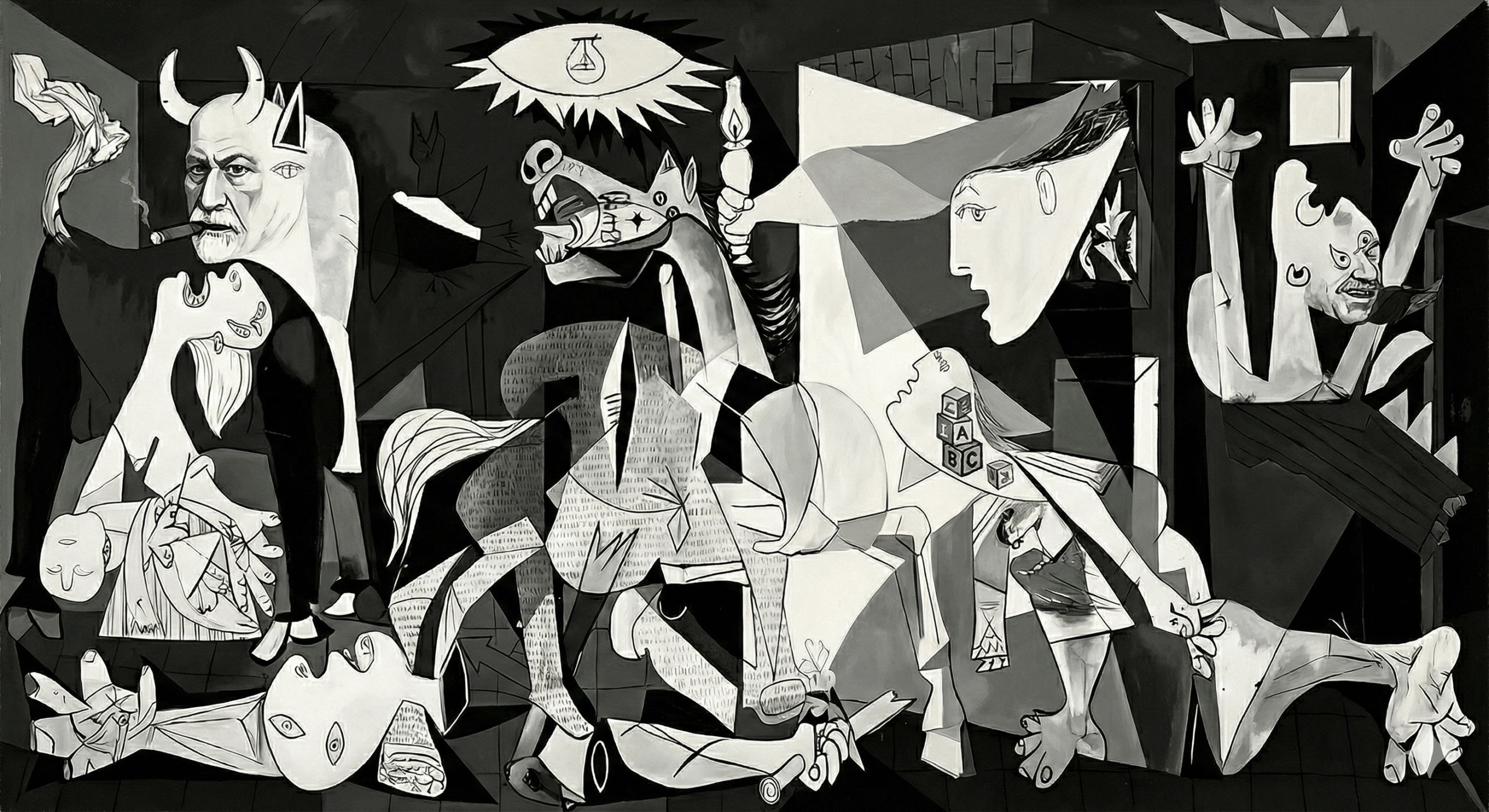

William James James Hillman and the Love of War

It was in the shadow of this conflict that William James the father of American psychology came of age. James did not fight in the war but he was deeply affected by it. His later work on the psychology of war was an attempt to reckon with the martial spirit that had consumed his generation. In his seminal essay The Moral Equivalent of War James acknowledged that war possessed a psychological utility that peace often lacked. War provided a sense of communal purpose discipline and self sacrifice that was deeply attractive to the human spirit. He argued that pacifists failed to understand this psychological appeal. Decades later the archetypal psychologist James Hillman would take this further in his provocative work A Terrible Love of War. Hillman argued that war is not merely a failure of human reason or a pathology to be cured but an inherent autonomous component of the human psyche. Drawing on the myth of the Roman god Mars Hillman suggested that war has its own terrible beauty and attraction that pulls the soul into its orbit. He argued that we cannot understand war by simply trying to prevent it we must understand the love we have for it the rush of adrenaline the camaraderie and the proximity to the sublime power of death. For Hillman war is a cosmological event that forces the soul to confront the absolute realities of existence. This perspective challenges the sanitized view of war as a political error and forces us to confront the Mars archetype living within the collective unconscious.

Shell Shock and Freud’s Disillusionment in World War I

The entry of the United States into World War I marked the beginning of the modern psychological era of warfare. It was the first conflict where the machinery of death seemed to completely eclipse the agency of the individual soldier leading to a new kind of psychological breakdown. The term shell shock emerged to describe the tremors paralysis and staring silences of men who had been subjected to the relentless artillery barrages of the Western Front. Initially the medical establishment debated whether this condition was physical caused by the concussive force of exploding shells or psychological caused by the sheer terror of the environment. The debate over shell shock was a turning point for the field of psychology. It forced the military and medical authorities to acknowledge that even the bravest soldiers could be broken by the environment of modern war. It was no longer a question of moral fiber but of psychological endurance. Sigmund Freud writing in 1915 captured the dark mood of the era in his essay Thoughts for the Times on War and Death. Freud argued that the war had brought about a profound disillusionment because it stripped away the veneer of civilization to reveal the primitive impulses that still lurked within the human psyche. He posited that civilization had not eradicated the violent instincts of man but merely repressed them. The war allowed these instincts to resurface with the sanction of the state. Freud observed that the state forbids the individual to do wrong not because it wishes to do away with wrongdoing but because it wishes to monopolize it. In his later correspondence with Albert Einstein titled Why War Freud introduced the concept of the death drive or Thanatos arguing that there is an instinctual drive in humans towards destruction and a return to the inorganic state. War he argued is the externalization of this death drive on a massive scale.

Carl Jung and the Archetype of Wotan in World War II

As the world moved toward the second global conflagration the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung offered a chilling analysis of the rising tide of fascism in Europe. Jung looked beyond the political and economic explanations to the mythological underpinnings of the conflict. In his 1936 essay Wotan Jung argued that Adolf Hitler was possessed by the archetype of Wotan the ancient Germanic god of storm and frenzy. Jung saw the Nazi movement not as a political aberration but as a mass psychosis resulting from the reawakening of a dormant collective unconscious. Wotan represented the irrational and uncontrollable forces of nature that civilization had tried to suppress. He was the god of the berserkers the unleasher of passions and the lust of battle. Jung argued that the German people by suppressing their own shadow side had made themselves vulnerable to possession by these archetypal forces. When a nation denies its own capacity for evil it projects that evil onto others and becomes consumed by the very forces it tries to repress. Jung’s analysis suggests that war is often a manifestation of a collective psychic infection a seizure of the rational mind by ancient and destructive powers. World War II was framed as the Good War a moral crusade against the absolute evil of fascism. Yet this moral clarity did not protect the soldiers from the psychological ravages of combat. The sheer duration of the war and the intensity of the fighting led to high rates of combat fatigue. The military began to recognize that every man had a breaking point. The phrase Old Sergeant Syndrome was used to describe experienced leaders who after too much exposure to death simply ceased to function effectively. The illusion of the invulnerable warrior was finally dispelled by the grinding reality of global war.

Finding Meaning in Suffering with Viktor Frankl

Out of the ashes of the Holocaust came one of the most profound psychological theories of the twentieth century. Viktor Frankl a Viennese psychiatrist was imprisoned in Auschwitz and other concentration camps. In the midst of that hell he observed that the prisoners who survived were often those who could find a sense of meaning in their suffering. Frankl argued that the primary drive in human life is not pleasure as Freud suggested or power as Adler suggested but the will to meaning. Frankl developed his theory of Logotherapy based on these experiences. He posited that even in the most hopeless circumstances a human being retains the last of the human freedoms to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances. Frankl’s work shifted the focus of therapy from the excavation of the past to the construction of a meaningful future. He developed techniques like paradoxical intention which helps patients overcome anxiety by embracing the very thing they fear and dereflection which helps patients break the cycle of self absorption by focusing on a meaning outside themselves. Frankl’s legacy is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the power of meaning to sustain us through the darkest of times.

Wilhelm Reich Somatic Armor and the Mass Psychology of Fascism

While Frankl looked to the heights of meaning to survive the camps his contemporary Wilhelm Reich looked to the biological depths to understand why the camps existed in the first place. Reich a student of Freud who was expelled from the psychoanalytic movement for his radicalism offered a somatic explanation for the rise of authoritarianism in his banned book The Mass Psychology of Fascism. Reich argued that fascism was not merely a political ideology imposed from above by dictators but was the organized political expression of the structure of the average man’s character. He posited that the suppression of natural sexuality in the child particularly the prohibition of genital pleasure by the authoritarian family created a blockage of biological energy or libido. This blockage hardened into what Reich called character armor a rigid psychological and physical defense mechanism that the individual uses to repress their own life force.

This repression does not simply make the individual neurotic it transforms their biological energy into sadistic rage and anxiety. The armored individual terrified of their own freedom and internal chaos longs for a strong leader to impose order from the outside. The swastika and the marching boot were not just political symbols but projections of the repressed violent unconscious of the masses. Reich famously asked why the masses did not revolt but instead fought for their servitude as if it were salvation. His answer was that their character structure had been molded to desire authority. In a tragic irony that illustrated his theories on the fear of freedom Reich died in a United States federal prison in 1957. The US government in a fit of Cold War paranoia regarding his later work on orgone energy ordered his books including his anti fascist masterpieces to be burned in a New York incinerator. This event remains one of the most significant examples of state censorship in American history and serves as a grim reminder that the emotional plague of authoritarianism is not confined to any single nation but is a latent potential in all armored societies.

Deleuze and Guattari Desire and the Micro Fascism of Everyday Life

In the wake of the social upheavals of the 1960s the French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari revolutionized the psychology of power with their seminal work Anti-Oedipus Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Moving beyond Freud’s family centered drama they argued that the unconscious is not a theater of mommy and daddy but a factory of production. They challenged the traditional view that fascism is solely the result of deception or repression arguing instead that on a certain level the masses desired fascism. This desire was not for pain but for a perverted form of security and identity found in the collective assemblage of the state. They introduced the terrifying concept of micro fascism the fascism that exists not in government buildings but in the minutiae of everyday life in the couple the family the school and the office.

Michel Foucault in his preface to their work called it an introduction to the non fascist life. He warned that the strategic adversary is not just the historical fascism of Hitler and Mussolini but the fascism in us all in our heads and in our everyday behavior the fascism that causes us to love power to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us. Deleuze and Guattari described the State as an apparatus of capture that attempts to code and control the flows of desire. Opposed to this is the War Machine a concept they developed in A Thousand Plateaus which represents the nomadic decentralized energy that resists state control. However they warned that the War Machine can be appropriated by the state turning its creative potential into pure destruction. This framework is essential for understanding the modern American political landscape where the battle is often not between clear ideological armies but is a rhizomatic struggle of micro fascisms fighting for control over the narrative of reality itself. It forces the clinician and the historian to ask not just what people believe but what they desire and how that desire has been engineered to turn against its own best interests.

Cold War Anxiety Brainwashing and Totalitarianism

The post war era brought a new kind of psychological terror. The looming threat of nuclear annihilation created a pervasive undercurrent of anxiety that permeated the culture. The Korean War introduced the American public to the fear of brainwashing. The sight of American POWs confessing to crimes they did not commit and denouncing their country sparked a panic about the fragility of the American mind. This led to a surge in research into the psychology of totalism and the mechanisms of thought reform. Joost Meerloo explored these themes describing them as menticide or the killing of the mind. He argued that totalitarian regimes use terror and confusion to break down the individual’s ego making them susceptible to suggestion and control. Erich Fromm another refugee from Nazi Germany explored the roots of the totalitarian impulse in his book Escape from Freedom. Fromm argued that modern man freed from the bonds of pre modern society often feels isolated and anxious. To escape this burden of freedom individuals may submit to authoritarian regimes that promise security and belonging at the cost of individuality. This psychological mechanism of automaton conformity helps explain the mass support for dictatorships and serves as a warning for democratic societies in times of crisis.

John Nash Game Theory and the Cold War Architecture of Paranoia

The transition from the hot war against fascism to the cold war against communism necessitated a fundamental restructuring of the American military mind. If the Revolutionary War was driven by the nervous sensibility of the body and the Civil War by the melancholic burden of the soul the Cold War was driven by the dissociated hyper rationality of the intellect. This era saw the rise of the defense intellectual a new class of warrior who fought not in the trenches but in the sterile conference rooms of the RAND Corporation. The defining psychological framework of this period was Game Theory a mathematical approach to conflict that sought to reduce the chaos of human behavior to predictable models of self interest. At the center of this intellectual revolution was John Nash a mathematician whose brilliance was matched only by his struggle with paranoid schizophrenia. Nash’s work particularly the concept of the Nash Equilibrium provided the theoretical architecture for the nuclear standoff. It posited a situation where no player can benefit by changing their strategy while the other players keep theirs unchanged leading to a state of frozen tension. In the context of nuclear warfare this translated to Mutually Assured Destruction a logical trap where the only rational move was to threaten suicide to prevent murder. This marked a profound psychological shift from the Clausewitzian view of war as politics by other means to a view of war as a non cooperative game where trust was not a virtue but a mathematical error.

The adoption of Game Theory by the military establishment represented a collective schizoid defense mechanism. By turning the prospect of nuclear annihilation into an abstract algebra of payload yields and kill probabilities the defense intellectuals could dissociate from the horrific reality of their calculations. The historian Peter Galison has described the ontology of the enemy in cybernetics and game theory not as a human being with emotions and a history but as a predictable information processor. This dehumanization was necessary to maintain the psychological stability of those whose fingers hovered over the button. However this hyper rationality had a shadow side. Just as John Nash’s mind eventually fractured into delusion the collective mind of the Cold War state descended into a form of institutional paranoia. The Red Scare the construction of backyard fallout shelters and the obsession with internal subversion were the societal manifestations of a psyche that had severed its connection to emotional reality in favor of a terrifying logic. The Prisoner’s Dilemma the most famous thought experiment of game theory taught a generation of policymakers that betrayal is often the most rational choice. This eroded the concept of diplomatic good faith and replaced it with a permanent posture of suspicion. The Cold War psyche was one of high functioning autism capable of immense technological and strategic complexity but utterly lacking in the theory of mind required for genuine empathy or peace.

The legacy of this period is a form of rational insanity that still infects geopolitical thinking. The belief that safety can only be achieved through the threat of total destruction is a remnant of the Nash Equilibrium. The psychological cost of this worldview is a chronic state of low level anxiety and a deep seated cynicism regarding human nature. John Nash eventually recovered from his schizophrenia by learning to ignore his delusions to recognize them as false patterns generated by his own mind. The challenge for the post Cold War American psyche is similar. It must learn to recognize that the zero sum game of global dominance is a delusion of the past and that the hyper rational paranoia of the twentieth century is no longer a viable survival strategy in an interconnected world. The integration of the Cold War shadow requires us to move beyond the fear based mathematics of survival and rediscover the human sensibility that the defense intellectuals tried so hard to repress.

Moral Injury and the Counterfeit Universe of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a watershed moment in the history of military psychology. It was a war that was morally ambiguous fought in a landscape where the enemy was often indistinguishable from the civilian population. Soldiers returned not to parades but to a country that was deeply divided and often hostile. This lack of social validation compounded the trauma of the war leading to what was initially called Post Vietnam Syndrome and later codified as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder PTSD in 1980. However the diagnosis of PTSD with its focus on fear conditioning and hyperarousal often failed to capture the full depth of the veteran’s experience. Robert Jay Lifton who worked with veterans in rap groups which were a precursor to modern group therapy identified a deeper wound related to the atrocity producing situations of the war. Lifton described the counterfeit universe of Vietnam where body counts became the measure of success and where the lines between combatant and civilian were blurred. He argued that many veterans were suffering not just from fear but from a sense of failed enactment and guilt over their participation in an immoral enterprise. This concept was further developed by the psychiatrist Jonathan Shay in his groundbreaking book Achilles in Vietnam. Shay compared the experiences of Vietnam veterans to the warriors in Homer’s Iliad arguing that the rage and withdrawal of Achilles were mirrored in the lives of modern soldiers. Shay coined the term moral injury to describe the psychological damage that occurs when there is a betrayal of what is right by someone who holds legitimate authority in a high stakes situation. For many Vietnam veterans the betrayal came from their own commanders who prioritized kill ratios over the safety of their men or from a government that lied about the progress of the war. This betrayal destroyed the social trust or themis that is essential for a soldier’s psychological survival. Shay’s work highlighted the importance of communalizing trauma. He argued that healing can only occur when the veteran’s story is heard and validated by a community that is willing to share the burden of the war. The rap groups of the Vietnam era were a vital mechanism for this allowing veterans to break the silence and shame that surrounded their experiences.

The Gulf War and the Simulacrum of Video Game Violence

The Gulf War of 1991 presented a new psychological paradigm the Video Game War. The conflict was characterized by the use of precision guided munitions and overwhelming air power which allowed the American public to view the war through the detached lens of gun camera footage. The French philosopher Jean Baudrillard argued in The Gulf War Did Not Take Place that the war was a simulacrum a media event constructed of signs and images that concealed the bloody reality of the conflict. For the western viewer the war was a sanitized spectacle devoid of dead bodies and suffering. However for the soldiers on the ground the reality was far from sanitized. The phenomenon of Gulf War Syndrome emerged in the aftermath of the conflict a mysterious constellation of symptoms including fatigue muscle pain and cognitive impairment. While some have attributed these symptoms to chemical exposure such as sarin gas or depleted uranium others have pointed to the psychological stress of the deployment and the disconnect between the sanitized public narrative and the reality of the battlefield. The ambiguity of the syndrome and the struggle for recognition by veterans echo the earlier struggles of Vietnam veterans for the recognition of Agent Orange effects.

The Psychology of the War on Terror and Drone Warfare

The attacks of September 11 2001 triggered a massive psychological response in the United States. The trauma of the attacks invoked a collective Terror Management response where the fear of death drove a surge in nationalism and support for charismatic leaders. Terror Management Theory based on the work of Ernest Becker suggests that when mortality is made salient people cling more tightly to their cultural worldviews and become more aggressive towards out groups. This psychological mechanism helps explain the broad public support for the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq as well as the tolerance for measures like the Patriot Act and enhanced interrogation techniques. The War on Terror also ushered in the age of drone warfare which has created a unique psychological landscape for operators. Unlike traditional pilots who are physically present in the combat zone drone operators fight from trailers in Nevada thousands of miles away from their targets. This physical distance creates a psychological dissonance often referred to as remote combat stress. Despite the distance operators often have a more intimate view of the kill than traditional pilots observing their targets for hours or days before striking and then witnessing the aftermath in high resolution. This can lead to a specific form of moral injury where the operator feels like a voyeur to death unable to share the physical risk of the combatants they are killing. Research has shown that drone operators suffer from rates of PTSD and moral injury comparable to those of deployed personnel challenging the notion that physical distance equates to psychological safety.

Killology and the Conditioning of the Modern Soldier

A critical area of study in modern military psychology is the mechanism by which soldiers are conditioned to kill. Lt Col Dave Grossman in his influential book On Killing argues that there is a natural resistance in most human beings to killing their own species. He cites S L A Marshall’s studies from WWII which claimed that only a small percentage of soldiers actually fired their weapons in combat. While Marshall’s data has been questioned Grossman’s thesis that the military has developed sophisticated conditioning techniques to overcome this resistance is widely accepted. Grossman identifies operant conditioning using realistic targets and immediate feedback as the primary method for increasing firing rates. This killology focuses on making the act of killing a reflex rather than a conscious decision. While this increases lethality on the battlefield it can have devastating psychological consequences when the soldier returns home. The reflex to kill combined with the desensitization to violence can make reintegration into civilian society incredibly difficult. The field of psychohistory founded by Lloyd deMause offers a provocative framework for understanding these cycles of violence. DeMause’s Psychogenic Theory of History posits that the central force in historical change is the evolution of childhood. He argues that the history of childhood is a nightmare from which we are only recently awakening and that the abusive child rearing practices of the past created adults who were filled with repressed rage and anxiety. These adults then projected their internal conflicts onto the political stage creating wars as a means of acting out their traumas. According to deMause war is often a collective reenactment of early childhood traumas where the enemy becomes the bad parent who must be destroyed while the nation itself becomes the good mother who must be defended. This theory suggests that the only way to end war is to improve the way we raise children moving from intrusive and socializing modes of child rearing to a helping mode that respects the child’s autonomy and emotional needs.

The Intellectual Lineage of War Psychology

The intellectual lineage of war psychology is a complex web of influence. Sigmund Freud remains the patriarch of the field influencing almost every subsequent thinker. His concept of the death drive and the fragility of civilization directly influenced Einstein with whom he corresponded on Why War and the Frankfurt School including Erich Fromm. Fromm’s analysis of authoritarianism bridges the gap between individual psychology and political structure influencing the political psychology of the Cold War. Carl Jung’s influence is less direct in clinical psychiatry but profound in the cultural analysis of war. His concept of the shadow and the collective unconscious informs the work of mythologically oriented psychologists like Jonathan Shay who uses ancient epic poetry to illuminate modern trauma. Shay’s work in turn has influenced the modern understanding of Moral Injury which has been adopted by the Department of Veterans Affairs and researchers like Brett Litz. Robert Jay Lifton represents the bridge between psychoanalysis and history. A member of the Wellfleet Psychohistory Group along with Erik Erikson Lifton’s work on psychic numbing and the protean self fundamentally changed how we understand the survivor experience. His influence is seen in the work of Lloyd deMause though deMause took the field in a more radical direction focusing on childhood trauma as the sole generator of historical events. Viktor Frankl’s legacy is distinct focusing on the existential rather than the psychoanalytic. His Logotherapy has influenced the positive psychology movement and the modern focus on post traumatic growth PTG. The idea that trauma can be a catalyst for spiritual deepening is a direct descendant of Frankl’s experiences in Auschwitz. Dave Grossman’s influence is primarily within the military and law enforcement communities. His Killology has shaped modern combat training though his theories on video games and violence remain contentious in academic psychology.

Clinical Implications for Moral Repair and Healing Trauma

The evolution of war psychology has had a profound impact on clinical practice. The treatment of trauma has moved from the disciplinary psychiatry of WWI which sought to shame or shock soldiers back to the front to the evidence based treatments of today. However the limitations of standard PTSD treatments like Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive Processing Therapy are becoming increasingly apparent especially for veterans suffering from moral injury. Clinical practice is now expanding to include the concept of Moral Repair. This involves therapies that address the spiritual and existential dimensions of trauma. One such technique is Adaptive Disclosure a modification of exposure therapy that specifically targets moral injury. In this therapy the veteran might imagine speaking to a compassionate moral authority such as a forgiving ancestor or religious figure to seek forgiveness and understanding. This allows for the processing of guilt and shame in a way that standard exposure therapy which focuses on fear does not. Impact of Killing IOK Treatment is another specialized approach. These are group therapies that focus specifically on the psychological consequences of taking a life helping veterans to articulate their guilt and find ways to make amends. The acknowledgment that killing damages the soul even when it is justified by the rules of war is a crucial step in the healing process. There has also been a resurgence of interest in Logotherapy the meaning centered therapy developed by Viktor Frankl. Techniques like Paradoxical Intention are used to treat the anticipatory anxiety often found in veterans. If a veteran is afraid of sweating or shaking in a social situation the therapist might encourage them to try to sweat as much as possible or shake as hard as they can. This paradoxical wish breaks the feedback loop of fear and allows the symptom to subside. Dereflection is another Logotherapy technique used to help veterans shift their focus away from their own symptoms and towards a meaningful task or person in the outside world helping to break the cycle of hyper reflection that characterizes PTSD.

Personal Applications Narrative Reconstruction and Embracing the Shadow

The lessons of war psychology extend far beyond the clinic and into the personal lives of all individuals because we are all fighting invisible wars in our private lives struggles with authority betrayal and the search for meaning. The realization that our personal struggles are often connected to larger historical and generational forces can be liberating because it allows us to move from a place of personal pathology where we feel there is something wrong with us to a place of historical witnessing where we realize we are carrying a burden from our time. One of the most powerful self help tools derived from this field is the practice of Narrative Reconstruction. Just as nations must construct a narrative of their wars to make sense of them individuals must construct a narrative of their own lives that integrates their traumas. This involves writing or speaking about the traumatic event not just as a horror story but as a pivotal moment that shaped one’s identity. Finding the red thread of meaning that runs through the suffering is the essence of Frankl’s will to meaning. We can also apply the technique of Dereflection in our daily lives. When we find ourselves consumed by anxiety or self focus we can ask ourselves what is waiting for us in the world. What task is calling to us. Who needs us right now. By shifting our attention to something outside ourselves a hobby a cause a loved one we can break the grip of the neurotic cycle. The concept of Moral Courage championed by Jonathan Shay reminds us that healing is an act of bravery. It requires the courage to face the truth of what was done and what was suffered and the courage to trust others again. It is a reminder that we are not solitary actors but part of a human community that shares a common vulnerability and a common capacity for resilience. We must also learn to embrace the Shadow as Jung taught. We must acknowledge our own capacity for darkness and aggression. Denying our aggression only leads to its projection onto others. By owning our shadow we become more whole and less likely to demonize those with whom we disagree. We must find our own moral equivalent of war as William James suggested. We must find constructive outlets for our aggressive energy whether it is intense physical exercise social activism or creative work. We must find a fight that is worthy of our energy and that contributes to the life of our community.

Continued Reading List

Sigmund Freud Thoughts for the Times on War and Death

Sigmund Freud Civilization and Its Discontents

Carl Jung Wotan

Carl Jung Two Essays on Analytical Psychology

James Hillman A Terrible Love of War

William James The Moral Equivalent of War

Viktor Frankl Man’s Search for Meaning

Robert Jay Lifton Home from the War

Jonathan Shay Achilles in Vietnam

Lloyd deMause The History of Childhood

Lloyd deMause The Origins of War in Child Abuse

Dave Grossman On Killing

Jean Baudrillard The Gulf War Did Not Take Place

0 Comments