You’ve had the experience. You’re usually calm, but suddenly you’re screaming at your partner over dishes. You’re normally logical, but you’re sobbing uncontrollably about something that “shouldn’t” matter. You’re typically easygoing, but you’ve become rigidly fixated on a minor detail. Afterward, you wonder: Was that really me?

That question became the title of psychologist Naomi Quenk’s groundbreaking work on what happens when stress pushes us into our least-developed psychological function. Her research explains why you become someone unrecognizable under pressure—and why this isn’t pathology but a natural, even necessary, part of psychological development.

Who Is Naomi Quenk?

Naomi Quenk, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist and one of the foremost authorities on the inferior function in Jungian typology. Her book Was That Really Me? How Everyday Stress Brings Out Our Hidden Personality (originally published as Beside Ourselves) remains the definitive text on how personality type manifests under stress.

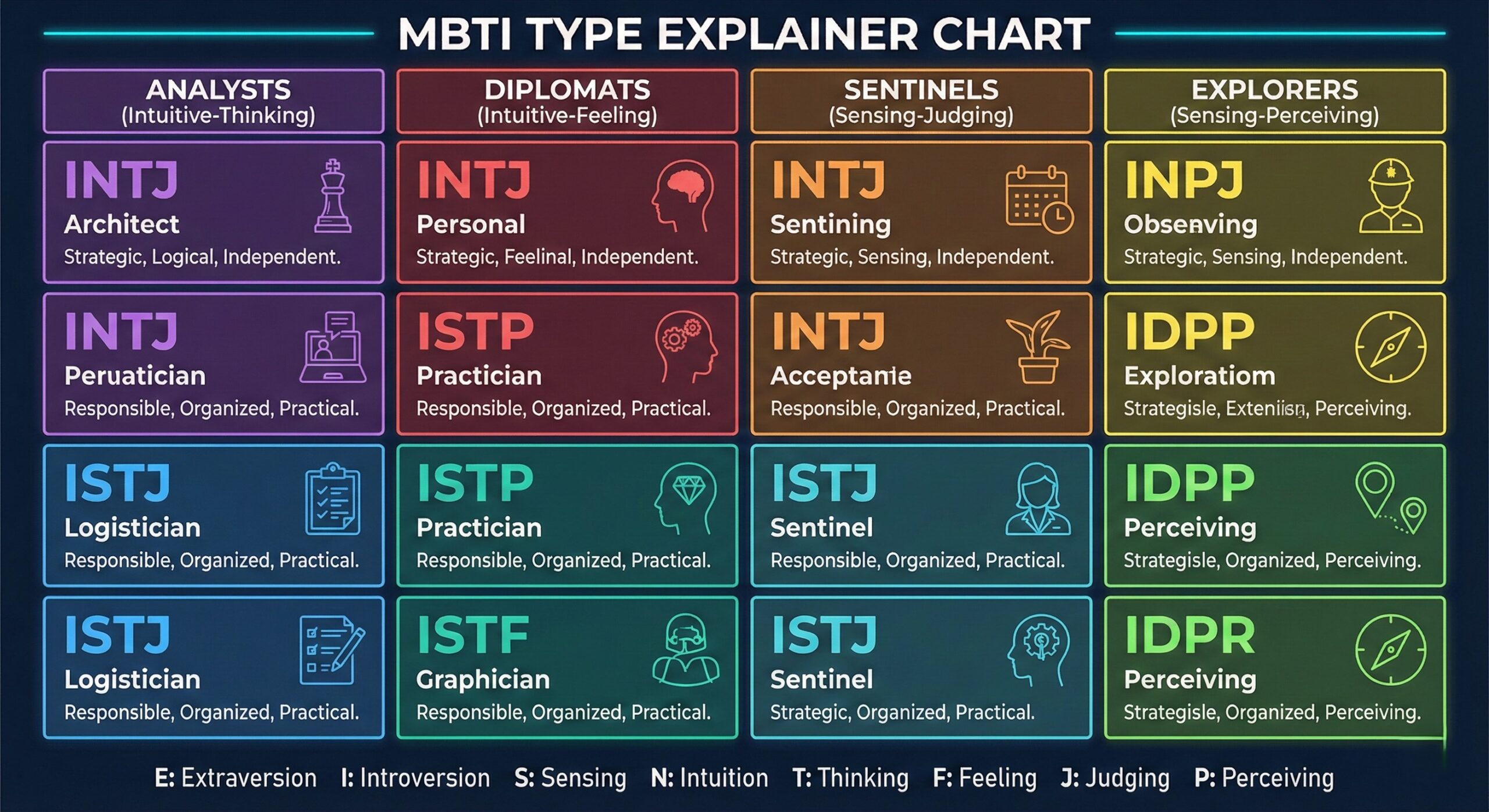

Quenk’s work built on Carl Jung’s theory of psychological types and its operationalization through the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). While much popular discussion of type focuses on preferences and strengths, Quenk illuminated the shadow side—what happens when our usual way of functioning gets overwhelmed.

The Architecture of Personality: Dominant and Inferior Functions

To understand Quenk’s contribution, you need to understand Jung’s model of cognitive functions. Jung proposed that we each have a preferred way of taking in information (Sensing or Intuition) and making decisions (Thinking or Feeling). These functions operate in a hierarchy:

The Dominant Function: Your Home Base

Your dominant function is your most developed, trusted, and comfortable mode of operating. It’s where you live psychologically. If your dominant function is Thinking, you naturally analyze, categorize, and apply logic. If it’s Feeling, you naturally evaluate based on values, harmony, and human impact. If it’s Sensing, you focus on concrete details and present reality. If it’s Intuition, you see patterns, possibilities, and future implications.

According to type dynamics theory, we develop our dominant function first and rely on it most heavily throughout life.

The Inferior Function: Your Achilles’ Heel

Your inferior function is the opposite of your dominant—the least developed, least trusted, and most unconscious part of your personality. It’s not that you can’t use it; you use it in a primitive, undifferentiated way that lacks the sophistication of your dominant function.

The inferior function operates largely outside conscious awareness. Jung described it as the doorway to the unconscious—the place where our shadow material lives. Jungian analysts recognize that the inferior function carries both our greatest vulnerability and our greatest potential for growth.

The pairings are fixed:

- Dominant Thinking → Inferior Feeling

- Dominant Feeling → Inferior Thinking

- Dominant Sensing → Inferior Intuition

- Dominant Intuition → Inferior Sensing

What Quenk Discovered: “In the Grip” Experiences

Quenk’s central contribution was systematically documenting what happens when stress, fatigue, illness, or overwhelm pushes people out of their dominant function and into the grip of their inferior function. She called these “in the grip” experiences.

Her research revealed consistent patterns:

The Characteristics of Grip Experiences

- They feel alien. People report feeling “not themselves,” possessed by something foreign. The usual personality seems to disappear.

- They’re triggered by stress. Fatigue, illness, excessive demands, unfamiliar situations, and unresolved conflicts all lower the threshold.

- They’re primitive. The inferior function expresses itself in crude, undifferentiated, all-or-nothing ways—unlike the nuanced expression of someone whose dominant function matches your inferior.

- They’re often projected. We see our inferior function in others and react to it there, criticizing in others what we can’t acknowledge in ourselves.

- They serve a purpose. Quenk framed grip experiences not as failures but as the psyche’s attempt to restore balance—forcing attention to neglected aspects of personality.

The Sixteen Types and Their Grip Experiences

Quenk documented specific grip patterns for each personality type. Here’s how each type tends to manifest when stress pushes them into their inferior function:

Types with Inferior Feeling (INTP, ISTP, ENTJ, ESTJ)

These types lead with Thinking—logical, analytical, objective. Under stress, they fall into inferior Extraverted Feeling or inferior Introverted Feeling:

- Hypersensitivity to relationships: Normally objective individuals become convinced others dislike them or are criticizing them.

- Emotional outbursts: Sudden crying, explosive anger, or overwhelming sentimentality that shocks both the person and those around them.

- Fear of being unloved: Deep, irrational conviction that they’re fundamentally unlovable or have damaged important relationships beyond repair.

- Value confusion: Rigid, black-and-white moral judgments replacing their usual nuanced analysis.

The normally detached analyst becomes flooded with emotions they can’t process, often expressed in ways that seem childish or excessive.

Types with Inferior Thinking (INFP, ISFP, ENFJ, ESFJ)

These types lead with Feeling—values-based, harmony-seeking, people-oriented. Under stress, they fall into inferior Thinking:

- Obsessive logic: Suddenly fixating on “being logical” in a rigid, cold way that feels harsh and uncharacteristic.

- Hypercritical analysis: Finding fault with everything and everyone, including themselves. Nothing is good enough.

- Adversarial debates: Picking fights, arguing points they don’t even care about, needing to be “right.”

- Truth-telling without tact: Blurting out harsh assessments with none of their usual sensitivity to impact.

The normally warm, considerate person becomes cutting, dismissive, and coldly judgmental.

Types with Inferior Intuition (ISTJ, ISFJ, ESTP, ESFP)

These types lead with Sensing—grounded in concrete reality, detail-oriented, practical. Under stress, they fall into inferior Intuition:

- Catastrophic imagination: Normally realistic individuals become convinced that disaster is imminent. Every symptom is cancer. Every noise is an intruder.

- Paranoid pattern-finding: Seeing sinister connections and hidden meanings everywhere. Conspiracy thinking.

- Apocalyptic visions: Certainty that everything is falling apart, that doom is approaching, that the worst-case scenario is inevitable.

- Loss of grounding: Feeling unmoored from reality, unable to trust their usual practical anchor.

The normally grounded, practical person becomes lost in dark fantasies about terrible futures.

Types with Inferior Sensing (INTJ, INFJ, ENTP, ENFP)

These types lead with Intuition—focused on patterns, possibilities, future implications. Under stress, they fall into inferior Sensing:

- Obsessive focus on body/physical details: Hypochondriacal concerns, fixation on minor physical sensations, convinced something is physically wrong.

- Overindulgence: Binge eating, drinking, shopping, or other sensory excess as an attempt to ground themselves.

- Rigid attention to facts: Demanding proof, evidence, and concrete verification in ways that seem paranoid or obsessive.

- Loss of vision: Inability to see possibilities or meaning. Everything becomes about immediate, mundane, physical concerns.

The normally visionary, big-picture person becomes trapped in physical minutiae, often with a quality of desperation.

Why This Matters Clinically

Quenk’s work has profound implications for therapy and self-understanding:

1. Grip States Aren’t Pathology

When clients describe feeling “possessed,” acting “crazy,” or becoming “someone else” under stress, Quenk’s framework offers normalization. These aren’t signs of mental illness—they’re predictable consequences of how personality functions under pressure.

This matters because shame about grip behavior often compounds the original stress. Understanding that everyone has an inferior function—and everyone falls into its grip sometimes—reduces self-judgment.

2. Grip States Often Appear in Therapy

Therapy itself is stressful. Exploring difficult material lowers defenses and can trigger grip states. Therapists who understand type dynamics can recognize when a client has fallen into their inferior function and respond appropriately—often by providing whatever the inferior function craves rather than pushing further.

For someone in inferior Feeling, this might mean offering warmth and reassurance rather than logical analysis. For someone in inferior Thinking, it might mean gently restoring their value perspective rather than engaging in debate.

3. The Inferior Function Points to Growth

Jung—and Quenk following him—saw the inferior function not just as vulnerability but as the path to individuation (psychological wholeness). The parts of ourselves we’ve neglected demand attention. Grip experiences, painful as they are, force us to develop capacities we’ve avoided.

The Thinking type who falls into inferior Feeling is being pushed to develop their emotional life. The Intuitive type overwhelmed by inferior Sensing is being forced to attend to physical reality. The discomfort is the growth.

4. Relationships Suffer from Mutual Grip States

When both partners in a relationship fall into their inferior functions simultaneously, the results are often catastrophic. Two people who normally relate well suddenly can’t recognize each other—or themselves. Conflicts escalate because both are operating from their least developed, most primitive capacities.

Understanding this pattern allows couples to recognize grip states and call timeouts rather than continuing to engage from depleted functioning.

What Triggers Grip Experiences?

Quenk identified common triggers that push people into their inferior function:

- Physical factors: Fatigue, illness, hunger, hormonal changes, chronic pain

- Psychological stress: Major life transitions, unresolved conflicts, accumulated minor stresses

- Environmental factors: Unfamiliar situations demanding use of the inferior function, prolonged time without access to dominant function activities

- Relational factors: Being around people who challenge or dismiss your dominant function, relationships that require constant inferior function use

The threshold varies by individual and circumstance. Someone well-rested with a strong support system can handle more before falling into the grip than someone already depleted.

Recovering from Grip States

Quenk’s research also documented effective recovery strategies:

General Principles

- Reduce stimulation. Most people need time alone, quiet, and reduced demands.

- Don’t force it. Trying to “snap out of it” usually backfires. The grip must run its course.

- Meet physical needs. Sleep, food, exercise often help restore equilibrium.

- Don’t make major decisions. Grip states distort judgment. Wait until you’re restored.

- Allow the experience. Fighting the grip prolongs it. Accepting that you’re in a temporary altered state paradoxically speeds recovery.

Type-Specific Recovery

Different types find different activities restorative:

- Inferior Feeling types often recover through structured physical activity, time alone, and returning to competence-building tasks.

- Inferior Thinking types often recover through connection with supportive others, engaging with values-affirming activities, and receiving validation.

- Inferior Intuition types often recover through engaging with trusted details and concrete tasks, being reminded of past successful coping, and physical grounding.

- Inferior Sensing types often recover through engaging with ideas and possibilities, creative activities, and permission to disengage from physical demands.

The Deeper Purpose: Integration and Wholeness

Quenk, following Jung, understood that the inferior function isn’t just a problem to manage—it’s an invitation to wholeness. The inferior function carries undeveloped potential.

In midlife especially, many people experience what Jung called the call to individuation—a growing pressure to develop neglected aspects of personality. The successful executive (dominant Thinking) begins craving emotional connection and meaning. The caring helper (dominant Feeling) starts wanting logical structure and personal achievement. The practical realist (dominant Sensing) becomes interested in spirituality and deeper patterns. The visionary idealist (dominant Intuition) begins attending to physical health and present-moment experience.

These aren’t random changes. They’re the psyche seeking balance—pushing us toward the wholeness that requires integrating what we’ve avoided.

Grip experiences, in this view, are forced encounters with what we’ve neglected. They’re painful precisely because the inferior function is undeveloped. But each encounter, survived and reflected upon, builds capacity. Over time, the inferior function can develop from a primitive, overwhelming force into a genuine resource.

Quenk’s Framework and Modern Neuroscience

While Quenk’s work predates contemporary neuroscience, her observations align with what we now know about stress and brain function.

Under chronic or acute stress, the prefrontal cortex—responsible for executive function and self-regulation—becomes compromised. When prefrontal control weakens, older brain systems (limbic, subcortical) exert more influence. Behavior becomes more reactive, less modulated, more primitive.

This maps remarkably well onto Quenk’s descriptions of grip states: the sophisticated, developed dominant function (associated with prefrontal integration) gives way to the crude, undifferentiated inferior function (associated with less-regulated subcortical activation).

Research on the Default Mode Network and stress also illuminates grip dynamics. Stress alters the balance between brain networks, potentially explaining why people shift into alien modes of processing under pressure.

Clinical Application: Working with Type in Therapy

At Taproot Therapy Collective, we integrate type awareness into our clinical work in several ways:

Assessment

Understanding a client’s personality type helps us anticipate their stress patterns, their likely grip experiences, and their recovery needs. It also helps us understand what kind of therapeutic approach will feel natural versus challenging—and when challenge is therapeutically useful.

Recognizing Grip States in Session

When a client suddenly presents very differently—the logical person flooded with emotion, the warm person becoming cold and critical—we consider whether a grip state is occurring. This changes the intervention. Someone in the grip often needs stabilization and acceptance before they can process content.

Understanding Resistance

Sometimes what looks like resistance is actually the client being pushed toward their inferior function before they’re ready. The Thinking-dominant client who can’t engage with emotional material isn’t being difficult; they’re being asked to operate from their most vulnerable place. Building capacity gradually, rather than demanding immediate access, respects the architecture of personality.

Growth Work

For clients interested in psychological development, we can work explicitly with the inferior function—not by forcing grip experiences, but by gradually building relationship with neglected aspects of personality. This might involve tracking when the inferior function appears, reflecting on what it wants, and finding safer ways to develop its capacities.

Applying This to Your Own Life

You don’t need to know your exact personality type to benefit from Quenk’s insights. Consider:

- What does “not yourself” look like for you? When stress takes over, what uncharacteristic behaviors emerge?

- What triggers these states? Notice patterns in what pushes you into alien territory.

- What helps you recover? What activities, environments, or interactions restore your usual functioning?

- What might your grip be asking for? The inferior function often carries legitimate needs that have been neglected. What is the primitive demand pointing toward?

Self-compassion is key. Grip experiences are humbling. Watching yourself behave in ways you’d judge harshly in others creates shame. But everyone has an inferior function. Everyone falls into its grip. The question isn’t whether you’ll have these experiences but whether you can learn from them.

Further Resources

If Quenk’s work resonates, consider exploring:

- Was That Really Me? by Naomi Quenk — The definitive text on inferior function dynamics

- Energies and Patterns in Psychological Type by John Beebe — Expands Jung’s model to eight functions with archetypal correlates

- Gifts Differing by Isabel Briggs Myers — The foundational text on type from the MBTI co-creator

- Psychological Types by Carl Jung — The original theoretical work, dense but rewarding

About This Article

This article was written by Joel Blackstock, LICSW-S, Clinical Director of Taproot Therapy Collective in Birmingham, Alabama. Joel integrates Jungian psychology, contemporary neuroscience, and somatic trauma approaches in his clinical work. Our practice specializes in complex trauma, depth-oriented therapy, and psychological development.

Key Sources:

- Quenk, N.L. (2002). Was That Really Me? How Everyday Stress Brings Out Our Hidden Personality. Davies-Black Publishing.

- Jung, C.G. (1921/1971). Psychological Types. Collected Works, Vol. 6. Princeton University Press.

- Beebe, J. (2016). Energies and Patterns in Psychological Type. Routledge.

- Myers, I.B. & Myers, P.B. (1995). Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Type. Davies-Black Publishing.

- Arnsten, A.F.T. (2015). Stress weakens prefrontal networks. Nature Neuroscience.

Last updated: January 2026

0 Comments