Who were the Major Influences on Carl Jung?

Read More on Jung here:

1. Jung’s Lifelong Journey into the Psychology of Religion

1.1 Index of Influences Mentioned in the Paper

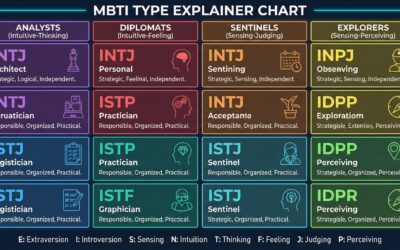

- Gnosticism influenced Jung through its emphasis on direct, experiential knowledge (gnosis) of the divine and the concept of the fallen, fragmented God-image. This led Jung to develop his understanding of the individuation process and the transformation of the God-image within the psyche.

- Friedrich Nietzsche influenced Jung through his concepts of the Übermensch and the Will to Power. This led Jung to develop his idea of the individuated Self and the role of psychological energy in the process of individuation.

- Martin Buber influenced Jung through his philosophy of dialogue and the I-Thou relationship. This led Jung to develop his understanding of the God-image as a symbol of the Self and the importance of a dialogical relationship between the ego and the Self.

- Meister Eckhart and Jakob Böhme influenced Jung through their mystical concepts of the “God beyond God” and the “ungrund.” This led Jung to develop his understanding of the apophatic dimension of the divine and the paradoxical nature of the Self.

- Eastern spirituality, particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism, influenced Jung through concepts such as Atman, Nirvana, and the Tao. This led Jung to develop his understanding of the collective unconscious, the individuation process, and the integration of opposites.

- Sabina Spielrein influenced Jung through her theories on the “death instinct” and the transformative power of the unconscious. This led Jung to develop his concept of the anima and the role of the feminine in the psyche.

- Anthropology and comparative mythology influenced Jung through the work of scholars like Jacob Burckhardt and Heinrich Zimmer. This led Jung to develop his theory of archetypes and the collective unconscious.

- Spiritualism and parapsychology influenced Jung through his engagement with the work of Theodore Flournoy and J.B. Rhine and Eugene Osty. This led Jung to develop his concept of synchronicity and his understanding of the interconnectedness of the psyche and the physical world.

- German Idealism and Romanticism influenced Jung through the work of philosophers such as Friedrich Schelling, Freidrich Hegel, and Wolfgang von Goethe. This led Jung to develop his understanding of the creative and transformative powers of the unconscious and the role of symbolism in the psyche.

- Immanuel Kant influenced Jung through his critique of reason and his emphasis on the limitations of human knowledge. This influenced Jung’s approach to the study of religious experience and his cautious attitude towards metaphysical speculation.

- Alchemy and Hermeticism influenced Jung through his study of alchemical texts and the work of thinkers like Hermes Trismegistus and Zosimos. This led Jung to develop his understanding of the individuation process as a symbolic and transformative journey.

- Phenomenology and existentialism influenced Jung through the work of philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and Jean Paul Sartre. This led Jung to develop his understanding of the psyche as a dynamic, embodied, and relational reality.

- Vitalism and evolutionary theory influenced Jung through the work of thinkers such as Henri Bergson and Hans Driesch. This led Jung to develop his understanding of the creative evolution of the psyche and the role of the collective unconscious in phylogenetic development.

- Christian and Jewish mysticism influenced Jung through his engagement with texts such as the Zohar and the work of mystics like Meister Eckhart. This led Jung to develop his understanding of the God-image, the Self, and the process of individuation as a spiritual journey.

- Islamic mysticism and Sufi thought influenced Jung indirectly through the work of Henry Corbin. Corbin’s concept of the mundus imaginalis and his interpretation of Islamic mystical texts led Jung to further develop his understanding of the imaginal realm, the archetypes, and the individuation process as a journey of spiritual transformation.

1.2 Overview of Jung

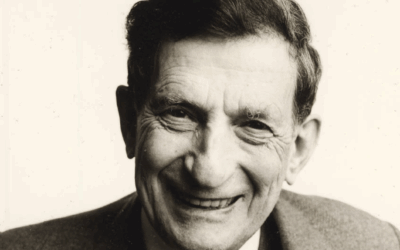

Carl Gustav Jung’s lifelong exploration of God and religion constitutes one of the most profound and influential contributions to the psychology of religion in the twentieth century. As a pioneer of depth psychology and the founder of analytical psychology, Jung sought to understand the psychological significance of religious experiences, symbols, and practices, and to integrate insights from various spiritual traditions into his theory of the psyche. Jung’s approach to religion was characterized by a deep appreciation for the transformative power of religious symbols and a recognition of the importance of the religious dimension of human experience for psychological wholeness and individuation.

The purpose of this essay is to provide a comprehensive overview of the development and influences of Jung’s thought on the God image, depth psychology and religion, from his early childhood experiences and intellectual influences to his mature formulations of key concepts such as the collective unconscious, archetypes, the God-image, and the Self. The essay will examine how Jung’s dialogue with various thinkers, such as Freud, Nietzsche, and Buber, shaped his understanding of religion, and how he incorporated insights from diverse spiritual traditions, such as Gnosticism, Christianity, and Eastern religions, into his depth psychology. The essay will also explore the controversies and criticisms surrounding Jung’s approach to religion, and assess the enduring significance and relevance of his ideas for contemporary psychology, theology, and spirituality.

2. Early Life and Influences

2.1 Childhood and Family Background

2.1.1 Religious upbringing and exposure to spirituality

Carl Gustav Jung was born on July 26, 1875, in Kesswil, Switzerland, to Paul Achilles Jung, a pastor in the Swiss Reformed Church, and Emilie Preiswerk Jung. Growing up in a family with a strong religious background, Jung was exposed to the spiritual and mystical dimensions of Christianity from a young age. His maternal grandfather, Samuel Preiswerk, was a prominent theologian and Hebraist who claimed to have visions and communicate with the dead. Jung’s early experiences of spirituality, including vivid dreams and visions, had a profound impact on his later psychological and religious thought.

2.1.2 Influence of his pastor father and the “religious life”

Jung’s relationship with his father, Paul Achilles Jung, played a significant role in shaping his attitude towards religion. As a pastor, Paul Jung struggled with his own faith and often expressed doubts about religious doctrines. Jung later described his father as a man who “suffered from religious doubts” and “was bitterly disappointed by the Church.” This exposure to religious ambivalence and the challenges of the “religious life” influenced Jung’s later critique of traditional Christianity and his emphasis on the importance of direct religious experience over dogma.

2.2 Education and Early Interests

2.2.1 University studies in medicine and psychiatry

After completing his secondary education, Jung enrolled at the University of Basel in 1895 to study medicine. During his medical studies, Jung became increasingly interested in the psychological aspects of human experience, particularly in the context of mental illness. In 1900, he began his psychiatric residency at the Burghölzli Mental Hospital in Zurich, under the supervision of Eugen Bleuler, a renowned psychiatrist who coined the term “schizophrenia.” Jung’s early medical and psychiatric training provided him with a scientific foundation for his later explorations of the psyche and the religious dimension of human experience.

2.2.2 Growing interest in the psychological aspects of religion

During his university years and early psychiatric career, Jung’s interest in the psychological aspects of religion deepened. He began to explore the writings of various philosophers, theologians, and mystics, such as Immanuel Kant, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Meister Eckhart, who addressed the relationship between the human psyche and the divine. Jung was particularly fascinated by the phenomena of religious conversion, mystical experiences, and the symbolic language of religious texts. These early intellectual interests laid the groundwork for his later development of a depth psychology that sought to understand the religious dimension of the psyche.

2.3 The Influence of Philosophy and Iconography

2.3.1 Influence of thinkers such as Schelling, Hegel, and Kant

Jung’s thought on God and religion was significantly influenced by his engagement with various philosophers, particularly those associated with German Idealism and Romanticism. The works of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and Immanuel Kant provided Jung with a philosophical framework for understanding the relationship between the human mind and the divine. Schelling’s concept of the “World Soul” and his emphasis on the unity of nature and spirit resonated with Jung’s later formulation of the collective unconscious. Hegel’s dialectical philosophy and his notion of the “Absolute Spirit” informed Jung’s understanding of the God-image as a symbol of psychological wholeness. Kant’s critique of reason and his emphasis on the limitations of human knowledge influenced Jung’s approach to the study of religious experience and his cautious attitude towards metaphysical speculation.

2.3.2 Fascination with religious symbolism and iconography, such as the sun disk in anthropology

In addition to his philosophical influences, Jung was deeply fascinated by religious symbolism and iconography from various cultures and historical periods. He was particularly interested in the recurring motif of the sun disk in ancient Egyptian, Babylonian, and Aztec religions, which he saw as a symbol of the Self, the central archetype of wholeness in his psychology. Jung’s study of sun symbolism in anthropology and comparative religion informed his later understanding of the God-image as a projection of the Self and his theory of the collective unconscious as a repository of universal religious symbols. This fascination with religious iconography also led Jung to explore other symbolic systems, such as alchemy, astrology, and Gnosticism, which he believed contained profound psychological insights into the nature of the divine and the process of individuation.

3. Relationship with Freud and the Development of Analytical Psychology

3.1 Collaboration with Freud

3.1.1 Initial fascination with Freud’s ideas on religion and the unconscious

Jung’s early intellectual development was significantly influenced by his relationship with Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. Jung first met Freud in 1907 and was initially fascinated by his ideas on the unconscious, the origin of religion, and the psychological interpretation of myth and symbolism. Freud’s theory of the Oedipus complex, which posited a universal psychosexual drama at the heart of human development and religion, resonated with Jung’s interest in the psychological significance of religious experiences and myths. Jung and Freud began a close collaboration, with Jung serving as the editor of the Jahrbuch für psychoanalytische und psychopathologische Forschungen, the leading journal of the psychoanalytic movement.

3.1.2 Joint exploration of religious themes in psychoanalysis

During their collaboration, Jung and Freud engaged in a joint exploration of religious themes in psychoanalysis. They discussed the psychological origins of religious beliefs, the symbolic meaning of religious rituals, and the role of the father figure in the development of the God-image. Jung was particularly interested in Freud’s theory of the “primal horde,” which traced the origin of religion to the guilt and ambivalence surrounding the primitive father figure. However, as their collaboration deepened, Jung began to develop his own ideas about the nature of the unconscious and the significance of religious symbolism, which diverged from Freud’s strictly sexual and individualistic interpretation.

3.2 Emerging Differences and Tensions

3.2.1 Disagreements on the nature and role of religion in the psyche

As Jung’s thought on religion and the psyche evolved, significant differences and tensions emerged between him and Freud. Jung increasingly challenged Freud’s reductionistic view of religion as a mere projection of infantile wishes and fears, and argued for a more complex and autonomous understanding of religious experience. While Freud saw religion as an illusion to be overcome through psychoanalytic insight, Jung believed that religion played a vital role in the process of individuation and the development of a healthy psyche. Jung also rejected Freud’s emphasis on sexuality as the primary driver of human behavior and religious symbolism, and instead emphasized the importance of a wide range of archetypal motifs and experiences in shaping the religious dimension of the psyche.

3.2.2 Jung’s growing emphasis on the collective unconscious and archetypal symbolism

A central point of divergence between Jung and Freud was Jung’s development of the concept of the collective unconscious and his emphasis on the universality of archetypal symbolism. While Freud’s theory of the unconscious focused primarily on individual repressed desires and memories, Jung argued for the existence of a deeper, transpersonal layer of the psyche that contained universal patterns and images shared by all of humanity. Jung saw religious symbols, such as the God-image, as expressions of these archetypal patterns, which he believed were essential for psychological growth and transformation. This emphasis on the collective and archetypal dimensions of the psyche set Jung’s approach apart from Freud’s and laid the foundation for his later development of analytical psychology as a distinct school of depth psychology.

4. Influences from Philosophy, Theology, and Mysticism

4.1 Gnosticism and its Impact on Jung’s Thought

4.1.1 Jung’s fascination with Gnostic texts and their psychological insights

One of the most significant influences on Jung’s thought on God and religion was his encounter with Gnosticism, a diverse set of religious and philosophical movements that flourished in the early centuries of Christianity. Jung first became fascinated with Gnostic texts and ideas during his medical studies and early psychiatric career, and he continued to explore Gnostic themes throughout his life. Jung was particularly drawn to the Gnostic emphasis on direct, experiential knowledge (gnosis) of the divine, and to the Gnostic myth of the fallen and fragmented God-image that could be restored through a process of spiritual awakening and transformation.

4.1.2 Incorporation of Gnostic themes into his concept of individuation and the God-image

Jung incorporated many Gnostic themes and symbols into his own depth psychology, particularly in his formulation of the concept of individuation and his understanding of the God-image. For Jung, the Gnostic myth of the fallen God-image, the Anthropos, who is scattered throughout the material world and must be redeemed through gnosis, served as a powerful metaphor for the process of individuation, the realization of the Self. Jung saw the Gnostic idea of the “Pleroma,” the fullness of divine being, as a symbol of the collective unconscious, and the Gnostic concept of the “Aeons,” the emanations of the divine, as a precursor to his theory of archetypes. Jung’s engagement with Gnosticism thus provided him with a rich symbolic language for articulating his own psychological understanding of the religious dimension of the psyche.

4.2 The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche

4.2.1 Jung’s interpretation and critique of Nietzsche’s ideas on religion and the “death of God”

Another significant influence on Jung’s thought on God and religion was the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, particularly his proclamation of the “death of God” and his critique of traditional Christianity. Jung was deeply fascinated by Nietzsche’s ideas, but also critical of what he saw as Nietzsche’s one-sided rejection of religion and his identification with the “Übermensch,” the superhuman figure who transcends conventional morality. For Jung, Nietzsche’s announcement of the death of God was a powerful psychological insight into the crisis of meaning and value in modern Western culture, but also a dangerous invitation to egoistic inflation and the neglect of the deeper, archetypal dimensions of the psyche.

4.2.2 Influence of Nietzsche’s concepts of the Übermensch and the Will to Power on Jung’s psychology

Despite his critiques of Nietzsche, Jung’s psychology was significantly influenced by Nietzschean concepts such as the Übermensch and the Will to Power. Jung saw the Übermensch as a symbol of the individuated Self, the fully realized personality that has integrated the conscious and unconscious dimensions of the psyche. However, Jung rejected Nietzsche’s glorification of the Übermensch as a supreme individual who creates his own values, and instead emphasized the importance of the collective unconscious and the archetypal foundations of the Self. Similarly, Jung interpreted Nietzsche’s concept of the Will to Power not as a drive for domination and self-assertion, but as a psychological energy that could be harnessed for the process of individuation and the realization of the Self. Jung’s engagement with Nietzsche thus involved a creative appropriation and transformation of Nietzschean ideas in the service of his own depth psychology.

4.3 Martin Buber and the I-Thou Relationship

4.3.1 Jung’s dialogue with Buber on the nature of the divine-human encounter

Jung’s thought on God and religion was also shaped by his dialogue with the Jewish philosopher and theologian Martin Buber, particularly around the nature of the divine-human encounter. Buber’s philosophy of dialogue, which emphasized the importance of the “I-Thou” relationship between the human person and the divine, resonated with Jung’s own understanding of the religious dimension of the psyche. Jung and Buber engaged in a series of conversations and correspondences, in which they explored the psychological and theological implications of the I-Thou relationship and its significance for the process of individuation.

4.3.2 Incorporation of Buber’s ideas into Jung’s understanding of the God-image and the Self

Jung incorporated many of Buber’s ideas into his own depth psychology, particularly in his understanding of the God-image and the Self. For Jung, the God-image was not merely a projection of individual desires and fears, but a symbol of the Self, the totality of the psyche that includes both conscious and unconscious elements. Jung saw the I-Thou relationship between the individual and the God-image as a crucial aspect of the individuation process, through which the ego learns to relate to the Self in a dialogical and transformative way. Jung also drew on Buber’s emphasis on the “eternal Thou,” the ultimate source of meaning and value that underlies all authentic I-Thou relationships, to develop his own understanding of the transpersonal dimension of the Self. Jung’s incorporation of Buberian themes thus deepened his psychological understanding of the religious dimension of human experience.

4.3.3 Disagreement and Falling Out Between Jung and Buber

Despite their initial resonance and mutual influence, Jung and Buber ultimately had a significant disagreement and falling out over the nature of the divine-human encounter and its implications for psychology and theology.

One major point of contention was Jung’s concept of the God-image as a psychological reality. Buber argued that Jung’s understanding of the God-image as a symbol of the Self risked reducing the divine to a mere projection of human consciousness. For Buber, the I-Thou relationship with God was not just a psychological phenomenon, but an ontological reality that transcended the individual psyche. Buber criticized Jung for what he saw as a psychologization of religion that failed to do justice to the alterity and transcendence of the divine.

Another area of disagreement was around the nature of evil and its relation to the divine. Jung’s concept of the shadow and his exploration of the dark side of the God-image in works like “Answer to Job” troubled Buber, who saw it as a dangerous blurring of the lines between good and evil. For Buber, the I-Thou relationship with God was fundamentally ethical and demanded a clear distinction between the divine and the demonic. Buber accused Jung of a kind of moral relativism that failed to take seriously the reality of evil and the need for human responsibility in the face of it.

These disagreements led to a cooling of the relationship between Jung and Buber and a mutual sense of disappointment and frustration. Buber came to see Jung’s psychology as a form of gnosticism that elevated the individual psyche to the status of the divine, while Jung saw Buber’s philosophy as an overly abstract and moralistic form of religiosity that failed to engage with the concrete realities of the psyche.

Despite their falling out, however, the dialogue between Jung and Buber remains an important moment in the history of psychology and religion, one that highlights the complex and often fraught relationship between the two disciplines. Their disagreements reveal the ongoing tension between psychological and theological understandings of the divine-human encounter and the challenges of integrating the two perspectives in a way that does justice to both the individual psyche and the transcendent nature of the divine.

4.4 Influences from Christian Mysticism and Eastern Spirituality

4.4.1 Jung’s study of Christian mystics such as Meister Eckhart and Jakob Böhme

In addition to his engagement with Gnosticism, Nietzsche, and Buber, Jung was deeply influenced by the tradition of Christian mysticism, particularly the works of Meister Eckhart and Jakob Böhme. Jung was fascinated by Eckhart’s concept of the “God beyond God,” the ineffable and apophatic dimension of the divine that transcends all human concepts and images. Jung saw Eckhart’s mystical theology as a powerful expression of the psychological process of individuation, through which the individual ego is transformed and united with the Self. Similarly, Jung was drawn to Böhme’s visionary cosmology and his emphasis on the “unground,” the mysterious and paradoxical source of all being that reconciles all opposites. Jung incorporated many of Eckhart’s and Böhme’s mystical symbols and ideas into his own depth psychology, particularly in his understanding of the God-image and the Self.

4.4.2 Incorporation of Eastern spiritual concepts, such as the Atman and the Tao, into his psychology

Jung’s thought on God and religion was also significantly influenced by his encounter with Eastern spirituality, particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Jung was fascinated by the concept of the Atman, the eternal and universal Self that underlies all individual selves, and saw it as a powerful symbol of the collective unconscious and the individuated personality. Jung also drew on the Buddhist concept of Nirvana, the state of ultimate liberation and enlightenment, to develop his own understanding of the goal of the individuation process. Similarly, Jung was deeply influenced by the Taoist concept of the Tao, the ineffable and paradoxical source of all being that reconciles all opposites, and saw it as a symbol of the Self and the God-image. Jung’s incorporation of Eastern spiritual concepts into his depth psychology thus expanded and enriched his understanding of the religious dimension of the psyche.

4.5 Sabina Spielrein and the Anima

4.5.1 Spielrein’s influence on Jung’s understanding of the feminine unconscious

Sabina Spielrein, a Russian physician and psychoanalyst, had a significant influence on Jung’s understanding of the feminine unconscious and the development of his concept of the anima. Spielrein was initially Jung’s patient and later became his student and colleague. Through their complex personal and professional relationship, Spielrein challenged Jung to reconsider the role of sexuality and the feminine in the psyche. Her own theories on the “death instinct” and the transformative power of the unconscious inspired Jung to delve deeper into the archetypal dimensions of the feminine psyche.

4.5.2 The development of the anima concept

Jung’s concept of the anima, the feminine aspect of the male psyche, was significantly influenced by his relationship with Spielrein and his engagement with her ideas. Spielrein’s emphasis on the creative and destructive aspects of sexuality, and her exploration of the archetypal “woman within” the male psyche, provided Jung with a framework for understanding the anima as a complex and dynamic structure of the unconscious. Jung’s theory of the anima, as the personification of the feminine unconscious in men, owes much to Spielrein’s pioneering work on the psychology of gender and the transformative power of the erotic.

4.6 The Influence of Anthropology and Comparative Mythology

4.6.1 The impact of Neolithic architecture and symbolism on Jung’s theory of archetypes

Jung’s theory of archetypes, as universal patterns of the collective unconscious, was significantly influenced by his study of Neolithic architecture and symbolism. The recurring motifs and symbols found in ancient stone circles, megaliths, and burial mounds, such as the spiral, the labyrinth, and the mandala, provided Jung with evidence for the existence of archetypal structures in the human psyche. Jung believed that these ancient symbols represented the archetypal patterns of transformation and individuation, and that their presence in diverse cultures and historical periods pointed to the universality of the collective unconscious.

4.6.2 The influence of mythologists and anthropologists such as Jacob Burckhardt, Heinrich Zimmer, Arnold van Gennep, and Friedrich Creuzer

Jung’s understanding of the collective unconscious and the archetypal dimensions of the psyche was also shaped by his engagement with the work of several key mythologists and anthropologists. Jacob Burckhardt’s studies of the cultural history of the Renaissance and the role of mythology in shaping cultural identity influenced Jung’s understanding of the relationship between individual psychology and collective cultural patterns. Heinrich Zimmer’s research on Indian philosophy and mythology, particularly his analysis of the symbolism of the mandala, provided Jung with a cross-cultural perspective on the archetypal dimensions of the psyche. Arnold van Gennep’s work on rites of passage and the structure of initiation rituals informed Jung’s understanding of the archetypal stages of the individuation process. Friedrich Creuzer’s studies of Greek and Roman mythology, and his theory of the “symbolical consciousness” of ancient peoples, influenced Jung’s understanding of the symbolic and mythological dimensions of the unconscious.

4.7 The Influence of Spiritualism and Parapsychology

4.7.1 Jung’s engagement with the work of Theodore Flournoy and the case of Hélène Smith

Jung’s early interest in spiritualism and parapsychology, and his engagement with the work of Swiss psychologist Theodore Flournoy, had a significant impact on his understanding of the unconscious and the development of his concept of the collective unconscious. Flournoy’s study of the medium Hélène Smith, who claimed to communicate with spirits from ancient civilizations and distant planets, fascinated Jung and provided him with evidence for the existence of subpersonalities and the creative powers of the unconscious. Jung’s analysis of Smith’s case, and his engagement with Flournoy’s theories on the “subliminal consciousness” and the “mythopoetic function” of the psyche, informed his later development of the concepts of the collective unconscious and the archetypes.

4.7.2 The influence of parapsychologists such as J.B. Rhine and Eugene Osty on Jung’s concept of synchronicity

Jung’s concept of synchronicity, as an acausal connecting principle between inner psychological states and outer events, was also influenced by his engagement with the work of parapsychologists such as J.B. Rhine and Eugene Osty. Rhine’s experiments on extrasensory perception (ESP) and psychokinesis (PK) at Duke University, and Osty’s studies of precognition and telepathy at the Institut Métapsychique International in Paris, provided Jung with empirical evidence for the existence of paranormal phenomena and the interconnectedness of the psyche and the physical world. Jung’s concept of synchronicity, as a principle of meaningful coincidence that transcends the boundaries of time and space, owes much to his dialogue with parapsychologists and his exploration of the frontiers of human consciousness.

4.8 The Influence of German Idealism and Romanticism

4.8.1 The impact of philosophers such as Friedrich Schelling, Friedrich Nietzsche, Immanuel Kant, and Friedrich Hegel on Jung’s understanding of the unconscious

Jung’s understanding of the unconscious and his theory of archetypes were significantly influenced by his engagement with the philosophy of German Idealism and Romanticism, particularly the work of Friedrich Schelling, Friedrich Nietzsche, Immanuel Kant, and Friedrich Hegel. Schelling’s concept of the “World Soul” and his emphasis on the creative and dynamic nature of the unconscious inspired Jung’s vision of the collective unconscious as a living and evolving reality. Nietzsche’s concept of the “Dionysian” aspect of human nature and his critique of traditional morality influenced Jung’s understanding of the shadow and the importance of integrating the dark side of the psyche. Kant’s theory of the “transcendental imagination” and his emphasis on the constructive powers of the mind shaped Jung’s understanding of the role of the unconscious in shaping reality. Hegel’s dialectical philosophy and his concept of the “Absolute Spirit” informed Jung’s understanding of the teleological nature of the psyche and the process of individuation.

4.8.2 The influence of Romantic thinkers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Hölderlin on Jung’s approach to symbolism and the imagination

Jung’s approach to symbolism and the imagination, and his emphasis on the creative and transformative powers of the unconscious, were also influenced by his engagement with the work of Romantic thinkers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Hölderlin. Goethe’s theory of “archetypal phenomena” and his emphasis on the symbolic and morphological dimensions of nature inspired Jung’s understanding of the archetypes as universal patterns of meaning and transformation. Hölderlin’s poetry and his exploration of the mythological and religious dimensions of the psyche influenced Jung’s understanding of the role of the imagination in the individuation process and the importance of integrating the sacred into everyday life. Jung’s approach to symbolism and the imagination, as key aspects of the individuation process and the dialogue between the conscious and the unconscious, owes much to his engagement with the Romantic tradition and its celebration of the creative powers of the human spirit.

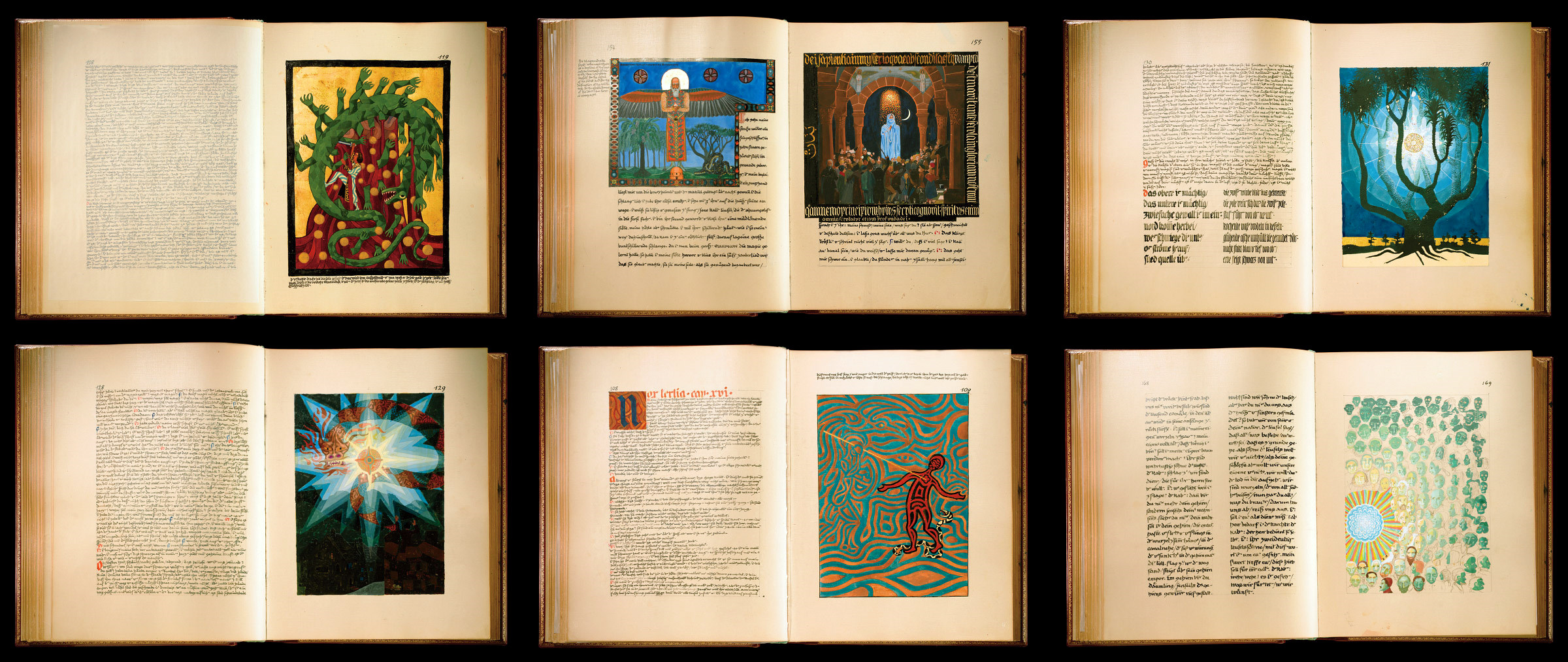

4.9 The Influence of Alchemy and Hermeticism

4.9.1 Jung’s study of alchemical texts and their impact on his understanding of the individuation process

Jung’s engagement with the Western esoteric tradition, particularly his deep study of alchemical texts, had a profound impact on his understanding of the individuation process and the transformation of the psyche. Jung saw in the alchemical opus a symbolic representation of the process of psychological transformation, with the stages of nigredo, albedo, and rubedo corresponding to the stages of the individuation process. The alchemical concept of the “philosopher’s stone,” as the ultimate goal of the opus, represented for Jung the archetype of the Self and the realization of psychic wholeness. Jung’s study of alchemical texts, such as those of Gerhard Dorn and Zosimos of Panopolis, provided him with a rich symbolic language for describing the process of individuation and the integration of the unconscious.

4.9.2 The influence of Hermetic thinkers such as Hermes Trismegistus, Jakob Boehme, and Emanuel Swedenborg on Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious

Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious, as a transpersonal dimension of the psyche that transcends individual experience, was also influenced by his engagement with the Hermetic tradition and the work of thinkers such as Hermes Trismegistus, Jakob Boehme, and Emanuel Swedenborg. The Hermetic concept of the “Anthropos,” the primordial human being who contains within himself all the powers of the cosmos, inspired Jung’s understanding of the Self as the archetype of wholeness and the center of the psyche. Boehme’s visionary philosophy, with its emphasis on the dynamic and polarized nature of reality, influenced Jung’s understanding of the role of opposites in the individuation process and the importance of integrating the shadow. Swedenborg’s mystical visions and his doctrine of correspondences between the spiritual and the natural worlds informed Jung’s understanding of the symbolic and archetypal dimensions of the psyche and the interconnectedness of all levels of reality.

4.10 The Influence of Phenomenology and Existentialism

4.10.1 The impact of philosophers such as Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty on Jung’s approach to the psyche

Jung’s approach to the psyche and his understanding of the relationship between consciousness and the unconscious were also influenced by his engagement with the philosophy of phenomenology and existentialism, particularly the work of Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Heidegger’s concept of “Being-in-the-world” and his emphasis on the ontological dimensions of human existence inspired Jung’s understanding of the psyche as a dynamic and embodied reality that is always already engaged with the world. Sartre’s concept of “bad faith” and his emphasis on the responsibility of the individual in shaping his or her own existence influenced Jung’s understanding of the role of consciousness in the individuation processand the importance of authenticity in the realization of the Self. Merleau-Ponty’s concept of the “lived body” and his emphasis on the perceptual and embodied dimensions of experience informed Jung’s understanding of the psyche as a living and incarnate reality that is always in dialogue with the world.

4.10.2 The influence of Gaston Bachelard and the French imagination on Jung’s approach to the poetic and the imaginal

Jung’s approach to the poetic and the imaginal dimensions of the psyche, and his emphasis on the transformative power of the creative imagination, were also influenced by his engagement with the work of French philosopher Gaston Bachelard and the tradition of the French imagination. Bachelard’s concept of the “material imagination” and his emphasis on the elemental and dynamic nature of the imaginal realm inspired Jung’s understanding of the archetypes as living and evolving structures of the psyche that are rooted in the natural world. Bachelard’s studies of the poetic imagination and the reverie, particularly his analysis of the symbolic meanings of fire, water, air, and earth, provided Jung with a framework for exploring the archetypal dimensions of the imagination and the role of the elements in the individuation process. Jung’s approach to the poetic and the imaginal, as key aspects of the dialogue between consciousness and the unconscious, owes much to his engagement with the French imagination and its celebration of the creative and transformative powers of the psyche.

4.11 The Influence of Vitalism and Evolutionary Theory

4.11.1 The impact of thinkers such as Henri Bergson and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin on Jung’s understanding of the creative evolution of the psyche

Jung’s understanding of the creative evolution of the psyche and his concept of the individuation process were also influenced by his engagement with the philosophy of vitalism and evolutionary theory, particularly the work of Henri Bergson and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Bergson’s concept of the “élan vital” and his emphasis on the creative and unpredictable nature of evolution inspired Jung’s understanding of the psyche as a living and dynamic reality that is always in the process of becoming. Teilhard de Chardin’s concept of the “Omega Point” and his vision of the evolutionary convergence of matter and spirit influenced Jung’s understanding of the teleological nature of the individuation process and the ultimate goal of psychic wholeness. Jung’s approach to the creative evolution of the psyche, as a process of differentiation and integration that is guided by the archetypal structures of the collective unconscious, owes much to his engagement with vitalism and evolutionary theory.

4.11.2 The influence of biologists such as Ernst Haeckel and Hans Driesch on Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious

Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious, as a biological and evolutionary foundation of the psyche, was also influenced by his engagement with the work of biologists such as Ernst Haeckel and Hans Driesch. Haeckel’s theory of recapitulation, which posited that the development of the individual organism mirrors the evolutionary history of the species, inspired Jung’s understanding of the archetypes as phylogenetic and ontogenetic structures of the psyche. Driesch’s concept of “entelechy” and his emphasis on the holistic and purposive nature of organic development influenced Jung’s understanding of the individuation process as a teleological and self-regulating process that is guided by the archetypal structures of the collective unconscious. Jung’s approach to the collective unconscious, as a biological and evolutionary foundation of the psyche that is expressed in the archetypal patterns of myth, religion, and culture, owes much to his engagement with the biological sciences and his attempt to integrate the insights of evolutionary theory into his depth psychology.

4.12 The Influence of Eastern Philosophy and Spirituality

4.12.1 Jung’s dialogue with Eastern thinkers such as D.T. Suzuki and his incorporation of Buddhist and Hindu concepts into his psychology

Jung’s understanding of the nature of the psyche and the process of individuation was also significantly influenced by his dialogue with Eastern philosophy and spirituality, particularly his engagement with Buddhist and Hindu thought. Jung’s dialogue with Japanese Zen master D.T. Suzuki, which began in the 1930s and continued until Suzuki’s death in 1966, had a profound impact on his understanding of the nature of the Self and the process of psychological transformation. Suzuki’s elucidation of the Zen concepts of “satori” (enlightenment) and “mu” (emptiness) inspired Jung’s understanding of the goal of individuation as a state of egoless awareness and inner liberation. Jung also incorporated Hindu concepts such as “Atman” (the universal Self) and “Brahman” (the ultimate reality) into his psychology, seeing them as analogues of the archetypes of the Self and the collective unconscious. Jung’s approach to the psyche and the individuation process, as a journey of self-discovery and spiritual transformation that transcends the boundaries of the ego, owes much to his dialogue with Eastern thought and his attempt to integrate the insights of Buddhist and Hindu spirituality into his depth psychology.

4.12.2 The influence of Taoist and Confucian thought on Jung’s approach to the integration of opposites and the realization of wholeness

Jung’s approach to the integration of opposites and the realization of psychic wholeness was also influenced by his engagement with Taoist and Confucian thought. The Taoist concept of “yin and yang,” which posits the complementarity and interdependence of opposite forces in nature, inspired Jung’s understanding of the role of opposites in the psyche and the importance of their integration for psychological health and spiritual growth. The Confucian emphasis on the cultivation of virtue and the harmonization of human relationships influenced Jung’s understanding of the ethical dimensions of the individuation process and the importance of social responsibility in the realization of the Self. Jung’s approach to the integration of opposites and the realization of wholeness, as a process of inner alchemy and outer transformation that involves the reconciliation of the individual with society and nature, owes much to his dialogue with Taoist and Confucian thought and his attempt to integrate the insights of Chinese philosophy into his depth psychology.

4.13 The Influence of Gnosticism and Western Esotericism

4.13.1 Jung’s fascination with Gnostic texts and their impact on his understanding of the God-image and the problem of evil

Jung’s understanding of the God-image and his approach to the problem of evil were significantly influenced by his fascination with Gnosticism and his deep study of Gnostic texts, particularly those found in the Nag Hammadi library. The discovery of the Nag Hammadi library in 1945 provided Jung with a wealth of new material to explore, including the Tripartite Tractate, which had a profound impact on his thought. Jung was particularly drawn to the Gnostic concept of the “Demiurge,” the inferior creator god who is responsible for the creation of the material world and the existence of evil, as outlined in texts such as the Tripartite Tractate. Jung saw in the Gnostic myth of the Demiurge a powerful expression of the dark side of the God-image and the psychological reality of the shadow. Jung’s engagement with Gnostic texts from the Nag Hammadi library, such as the “Apocryphon of John,” the “Pistis Sophia,” and the Tripartite Tractate, provided him with a framework for exploring the archetypal dimensions of the God-image and the role of evil in the individuation process. Jung’s approach to the God-image and the problem of evil, as expressions of the complex and dynamic nature of the psyche, owes much to his fascination with Gnosticism, especially the texts of the Nag Hammadi library, and his attempt to integrate the insights of this ancient esoteric tradition into his depth psychology.

4.13.1.1 Influence on Different Concepts and Branches of Gnosticism

The “Apocryphon of John” is a Sethian Gnostic text that presents a creation myth involving the Demiurge, a lower creator god who is ignorant of the true, higher God. This text portrays the material world as a flawed creation of the Demiurge, with humanity trapped in a state of ignorance and suffering. The “Apocryphon of John” also introduces the concept of Sophia, the divine feminine wisdom, whose fall from grace leads to the creation of the Demiurge. Jung was fascinated by this text’s portrayal of the Demiurge and the role of Sophia in the Gnostic cosmology.

The “Pistis Sophia” is a Gnostic text that focuses on the figure of Sophia, the divine feminine wisdom, and her fall from grace and ultimate redemption. This text portrays Sophia as a complex figure who undergoes a process of suffering, repentance, and redemption, which Jung saw as analogous to the individuation process in depth psychology. Jung was particularly interested in the “Pistis Sophia” for its exploration of the feminine aspect of the divine and its portrayal of the psychological process of transformation.

The Tripartite Tractate is a Valentinian Gnostic text that presents a complex cosmology involving the Pleroma (the fullness of divine beings), the Demiurge, and the material world. This text portrays the creation of the world as the result of a divine drama in which Sophia, the last of the divine beings, falls from grace and gives birth to the Demiurge. The Tripartite Tractate also explores the nature of the human soul and its potential for spiritual liberation through gnosis, or divine knowledge. Jung was intrigued by the Tripartite Tractate’s portrayal of the Pleroma and the role of Sophia in the creation of the world.

4.13.2 The influence of Western esoteric thinkers such as John Scottus Eriugena, Pseudo-Dionysius, Nicholas of Cusa, and Amalric of Bena on Jung’s concept of the Self and the process of individuation

Jung’s concept of the Self and his understanding of the process of individuation were also influenced by his engagement with the Western esoteric tradition and the work of thinkers such as John Scottus Eriugena, Pseudo-Dionysius, Nicolas of Cusa, and Amalric of Bena. Eriugena’s concept of the “division of nature” and his emphasis on the ultimate unity of all things in the divine inspired Jung’s understanding of the Self as the archetype of wholeness and the goal of the individuation process. Pseudo-Dionysius’ apophatic theology and his concept of the “divine darkness” influenced Jung’s understanding of the ineffable and paradoxical nature of the Self and the importance of embracing the unknown in the journey of self-discovery. Nicholas of Cusa’s concept of the “coincidence of opposites” and his emphasis on the infinite nature of God informed Jung’s understanding of the Self as a coincidentia oppositorum and the ultimate reconciliation of all dualities in the psyche. Amalric of Bena’s pantheistic philosophy and his concept of the “indistinction” of God and creation inspired Jung’s understanding of the immanence of the Self in all things and the ultimate unity of the individual with the cosmos. Jung’s approach to the Self and the individuation process, as a journey of self-discovery and spiritual transformation that involves the integration of opposites and the realization of wholeness, owes much to his engagement with the Western esoteric tradition and his attempt to integrate the insights of these thinkers into his depth psychology.

4.14 The Influence of Contemporary Psychology and Psychiatry

4.14.1 Jung’s relationship with Eugen Bleuler and the Burghölzli school

Jung’s early development as a psychiatrist and his approach to the study of the psyche were significantly influenced by his relationship with Eugen Bleuler and his involvement with the Burghölzli school of psychiatry in Zurich. Bleuler, who was Jung’s supervisor and mentor at the Burghölzli, was a pioneering figure in the field of psychiatry and is best known for his work on schizophrenia and his introduction of the concept of “ambivalence.” Bleuler’s emphasis on the psychological and symbolic dimensions of mental illness, and his use of innovative therapeutic techniques such as hypnosis and word association, had a profound impact on Jung’s early work and his approach to the study of the unconscious. Jung’s involvement with the Burghölzli school, which was at the forefront of psychiatric research and treatment in the early 20th century, provided him with a rich intellectual environment and a platform for developing his own theories and methods. Jung’s early work on the psychology of dementia praecox (schizophrenia) and his use of word association tests to explore the unconscious, which he conducted under Bleuler’s supervision, laid the foundation for his later development of analytical psychology and his theory of the collective unconscious.

4.14.2 The influence of psychologists such as Pierre Janet and Herbert Silberer on Jung’s understanding of the unconscious

Jung’s understanding of the nature and dynamics of the unconscious was also influenced by his engagement with the work of contemporary psychologists such as Pierre Janet and Herbert Silberer. Janet, who was a French psychologist and a pioneer in the study of dissociation and traumatic memory, had a significant impact on Jung’s early work and his approach to the treatment of psychogenic disorders. Janet’s concept of “psychological automatism” and his emphasis on the role of dissociation in the formation of psychopathology influenced Jung’s understanding of the autonomy of the unconscious and the importance of integrating dissociated aspects of the psyche in the process of healing. Silberer, who was an Austrian psychoanalyst and a contemporary of Freud and Jung, had a significant influence on Jung’s understanding of the symbolic and archetypal dimensions of the unconscious. Silberer’s work on the “functional phenomenon” and his emphasis on the transformative power of symbolic imagery inspired Jung’s approach to the interpretation of dreams and his theory of the archetypes. Jung’s understanding of the unconscious, as a creative and autonomous dimension of the psyche that is expressed through symbolic and archetypal imagery, owes much to his engagement with the work of these contemporary psychologists and his attempt to integrate their insights into his own depth psychology.

4.14.3 Jung’s engagement with Corbin’s work on the imaginal realm and the mundus imaginalis

Jung’s understanding of religious experience and the nature of the psyche was significantly influenced by his engagement with the work of French philosopher and Islamicist Henri Corbin, particularly Corbin’s concept of the imaginal realm or mundus imaginalis. Corbin, who was a scholar of Islamic mysticism, described the imaginal realm as an intermediary world between the sensory and the intellectual, a realm of archetypal images and symbols that are experienced as objectively real. This concept resonated deeply with Jung’s own understanding of the psyche as a realm of autonomous images and archetypes that possess a numinous and transformative power.

Jung was particularly intrigued by Corbin’s work on the visionary experiences of Islamic mystics such as Ibn Arabi and Suhrawardi, who described their encounters with the imaginal realm and its inhabitants, the archetypal figures and beings that populate the Islamic spiritual universe. For Jung, these accounts provided a powerful confirmation of his own intuitions about the psychological significance of religious phenomena, and the existence of a collective unconscious that transcends individual and cultural boundaries. Jung saw in Corbin’s work a validation of his own approach to the study of religion, which emphasized the primacy of direct experience and the symbolic and transformative dimensions of religious life.

4.14.4 The incorporation of Islamic mystical concepts into Jung’s psychology of religion

Jung’s engagement with Corbin’s work and Islamic mysticism had a profound impact on his psychology of religion, leading him to incorporate key concepts and ideas from this tradition into his own theoretical framework. One of the most significant of these was the concept of the “imaginal world” or “alam al-mithal,” which Jung saw as a powerful metaphor for the collective unconscious and the archetypal realm. Just as the Islamic mystics described the imaginal world as a realm of archetypal images and beings that possess an objective reality, Jung understood the collective unconscious as a transpersonal dimension of the psyche that contains universal patterns and symbols.

Jung was also deeply influenced by Corbin’s interpretations of Islamic mystical texts and practices, which emphasized the transformative and symbolic dimensions of religious experience. Corbin’s work on the spiritual hermeneutics of Islamic mysticism, and his emphasis on the power of symbolic and mythological language to express and evoke spiritual realities, resonated with Jung’s own approach to the interpretation of religious symbols and experiences. Jung incorporated many of these ideas into his own psychology of religion, seeing in them a confirmation of his own intuitions about the psychological significance of religious phenomena.

Moreover, Corbin’s work on the “theophanic imagination” and the idea of the “divine guide” or “personal angel” also had a significant impact on Jung’s understanding of the individuationprocess and the role of the Self in spiritual transformation. Just as the Islamic mystics described the experience of encountering a divine guide or personal angel who leads the seeker on the path of spiritual realization, Jung understood the Self as an inner guide and source of wisdom that leads the individual towards wholeness and integration.

4.15 The Influence of Jewish Mysticism

4.15.1 Jung’s engagement with the Zohar and Kabbalistic thought

Jung’s understanding of God and the psyche was significantly influenced by his engagement with Jewish mysticism, particularly the Zohar and Kabbalistic thought. The Zohar, the central text of the Kabbalah, presents a complex and symbolic understanding of the divine nature and the process of creation that resonated deeply with Jung’s own ideas about the God-image and the individuation process. Jung was particularly fascinated by the Kabbalistic concept of Ein Sof, the infinite and unknowable divine essence that transcends all categories and images. For Jung, Ein Sof represented the ultimate reality of the Self, the transcendent totality of the psyche that lies beyond the ego and the conscious mind.

Jung also drew on the Kabbalistic doctrine of the sefirot, the ten emanations or attributes of God that structure the process of creation, to develop his own understanding of the archetypes and the stages of individuation. Jung saw the sefirot as symbolic expressions of the different aspects and potentialities of the God-image, and as a framework for understanding the process of psychic transformation and realization.

4.15.2 The influence of Martin Buber and the dialogical principle

In addition to the Zohar and Kabbalistic thought, Jung was also deeply influenced by the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber and his concept of the dialogical principle. Buber’s I-Thou philosophy, which emphasized the transformative power of direct, mutually-affirming relationships between persons and between the individual and God, had a significant impact on Jung’s understanding of the God-image and the process of individuation. For Jung, the I-Thou relationship represented the highest form of human encounter and the key to unlocking the deeper layers of the psyche.

Jung drew on Buber’s ideas to develop his own understanding of the importance of dialogue and relationship in the process of psychic transformation. Jung saw the dialogical encounter between the ego and the Self, and between the conscious and unconscious aspects of the psyche, as essential for the realization of wholeness and the integration of the God-image. Jung also emphasized the importance of dialogical relationships in the therapeutic process, and saw the analyst-analysand relationship as a crucial container for the emergence of the numinous and the sacred.

4.15.3 The incorporation of Hasidic and other Jewish mystical concepts

Jung’s engagement with Jewish mysticism also extended to other traditions and figures, such as the Hasidic masters and the Jewish philosopher Abraham Heschel. Jung was fascinated by the Hasidic emphasis on joy, ecstatic prayer, and the immanence of God in everyday life, and saw these as powerful expressions of the numinous dimension of human experience. Jung also drew on Heschel’s concept of “radical amazement” and his understanding of the divine-human relationship as a call to ethical and spiritual responsibility.

Jung incorporated many Hasidic and other Jewish mystical concepts and practices into his own life and work, such as the use of ritual, chant, and sacred texts as tools for accessing the deeper layers of the psyche. Jung’s engagement with Jewish mysticism thus represents a significant and often overlooked aspect of his intellectual and spiritual journey, and has important implications for understanding his psychology of religion as a whole.

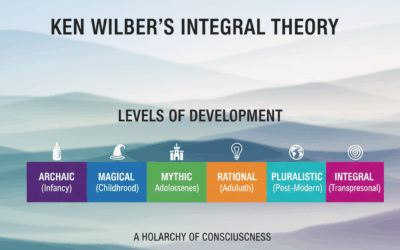

5. The Development of Jung’s Key Ideas on God and Religion

5.1 The Collective Unconscious and Archetypes

5.1.1 The God-image as an archetype of the collective unconscious

One of Jung’s most significant contributions to the psychology of religion was his concept of the God-image as an archetype of the collective unconscious. For Jung, the God-image was not merely a projection of individual desires and fears, but a universal and autonomous symbol of the Self, the totality of the psyche that includes both conscious and unconscious elements. Jung argued that the God-image was a central archetype of the collective unconscious, a transpersonal layer of the psyche that contains universal patterns and symbols shared by all of humanity. Jung saw the God-image as a powerful symbol of psychological wholeness and transformation, and believed that the process of individuation involved a confrontation and integration of the God-image into the conscious personality.

5.1.2 The role of religious symbolism in the individuation process

Jung’s understanding of the God-image as an archetype of the collective unconscious was closely linked to his emphasis on the role of religious symbolism in the individuation process. For Jung, religious symbols were not merely historical or cultural artifacts, but living expressions of the archetypal dimensions of the psyche. Jung believed that the symbols and myths of the world’s religions contained profound psychological truths and insights, and that the process of individuation involved a creative engagement with these symbols in order to integrate the conscious and unconscious aspects of the personality. Jung saw the individuation process as a spiritual journey, in which the individual ego learns to relate to the Self and the God-image in a dialogical and transformative way, and in which religious symbols serve as guides and mediators of this process.

5.2 The God-Image and the Self

5.2.1 The evolution of the God-image throughout the individuation process

For Jung, the God-image was not a static or fixed symbol, but a dynamic and evolving archetype that undergoes transformation throughout the individuation process. Jung believed that the God-image initially appears in a primitive and undifferentiated form, as a projection of the individual’s unconscious desires and fears. As the ego begins to confront and integrate the contents of the unconscious, the God-image undergoes a process of differentiation and personalization, becoming more complex and multifaceted. Jung saw this evolution of the God-image as a crucial aspect of the individuation process, through which the individual develops a more mature and authentic relationship to the Self and the religious dimension of the psyche.

5.2.2 The Self as the central archetype of wholeness and the “God within”

Jung’s understanding of the God-image was closely tied to his concept of the Self, which he saw as the central archetype of wholeness and the “God within.” For Jung, the Self was the totality of the psyche, including both conscious and unconscious elements, and the ultimate goal of the individuation process. Jung believed that the Self was the source of meaning, purpose, and value in human life, and that the realization of the Self involved a confrontation and integration of the God-image. Jung saw the Self as a paradoxical and numinous symbol, which transcends the ego and the conscious personality, and which serves as the guiding principle of the individuation process. Jung’s emphasis on the Self as the “God within” thus provided a psychological foundation for his understanding of the religious dimension of human experience.

5.3 The Problem of Evil and the Shadow

5.3.1 Jung’s critique of the Christian doctrine of privatio boni

Jung’s thought on God and religion was also significantly shaped by his confrontation with the problem of evil, particularly in relation to the Christian doctrine of privatio boni. According to this doctrine, which was developed by Augustine and other early Christian thinkers, evil is not a positive reality, but merely the absence or privation of good. Jung rejected this view, arguing that it failed to account for the reality and autonomy of evil in human experience. Jung believed that evil was a real and active force in the psyche, and that the confrontation with evil was a necessary aspect of the individuation process. Jung saw the Christian doctrine of privatio boni as a defensive and one-sided attempt to protect the image of a good and omnipotent God, which ultimately denied the reality of human suffering and the complexity of the psyche.

5.3.2 The integration of the Shadow as a crucial aspect of religious development

Jung’s critique of the Christian doctrine of privatio boni was closely linked to his emphasis on the integration of the Shadow as a crucial aspect of religious development. For Jung, the Shadow was the dark and rejected aspect of the personality, which contains the qualities and impulses that the ego finds unacceptable or threatening. Jung believed that the confrontation with the Shadow was a necessary stage in the individuation process, through which the individual learns to accept and integrate the darker aspects of the psyche. Jung saw the integration of the Shadow as a religious and moral task, which involves a humble acknowledgment of one’s own capacity for evil and a compassionate acceptance of the human condition. Jung’s emphasis on the Shadow thus provided a psychological foundation for his critique of traditional Christian theodicy and his call for a more honest and realistic approach to the problem of evil.

5.4 Synchronicity and the Interconnectedness of Psyche and Matter

5.4.1 Jung’s concept of synchronicity as a “modern myth” of divine-human interaction

Another significant aspect of Jung’s thought on God and religion was his concept of synchronicity, which he saw as a “modern myth” of divine-human interaction. For Jung, synchronicity referred to the meaningful and acausal connection between inner psychological states and outer events, which he believed revealed the underlying unity and interconnectedness of psyche and matter. Jung saw synchronicity as a principle that complemented the principle of causality, and which pointed to a deeper, archetypal dimension of reality. Jung believed that experiences of synchronicity were often associated with numinous and transformative moments in the individuation process, in which the individual ego encounters the Self and the God-image. Jung’s concept of synchronicity thus provided a psychological and mythological framework for understanding the religious dimension of human experience in a modern, scientific context.

5.4.2 The implications of synchronicity for the relationship between psychology and religion

Jung’s concept of synchronicity had significant implications for the relationship between psychology and religion, and for the understanding of the religious dimension of the psyche. By positing a meaningful and acausal connection between inner psychological states and outer events, Jung challenged the strict separation between the subjective and objective realms, and the reduction of religious experience to purely psychological or neurological factors. Jung’s concept of synchronicity suggested that the religious dimension of human experience was not merely a projection or illusion, but a real and autonomous aspect of reality that required a more holistic and integrative approach. At the same time, Jung’s emphasis on the psychological and mythological significance of synchronicity also challenged traditional religious understandings of divine intervention and miracles, and called for a more nuanced and symbolic approach to religious experience. Jung’s concept of synchronicity thus served as a bridge between psychology and religion, and provided a framework for a more dialogical and transformative understanding of the religious dimension of the psyche.

5.5 The Relationship between Psychology and Religion

5.5.1 Jung’s critique of traditional religious doctrines and his emphasis on individual religious experience

Jung’s approach to the relationship between psychology and religion was characterized by a critical stance towards traditional religious doctrines and an emphasis on the primacy of individual religious experience. Jung believed that the dogmatic and institutional aspects of religion often obscured the authentic and transformative nature of religious experience and that the task of psychology was to help individuals rediscover the living reality of the sacred within themselves. Jung’s critique of traditional religious doctrines, such as the Christian doctrine of the Trinity and the doctrine of original sin, was based on his belief that these doctrines were often too abstract and intellectual and failed to capture the emotional and symbolic dimensions of religious experience. Jung argued that the true meaning of religious symbols and myths could only be understood through a psychological and experiential approach that took into account the individual’s unique history and context. Jung’s emphasis on individual religious experience, as opposed to collective religious belief, was a central aspect of his approach to the relationship between psychology and religion and his vision of a new, more authentic spirituality for the modern age.

5.5.2 The role of psychology in the renewal and transformation of religion in the modern world

For Jung, the role of psychology in the modern world was not simply to explain or analyze religious experience, but to actively contribute to the renewal and transformation of religion itself. Jung believed that the crisis of meaning and purpose that characterized modern society was largely due to the loss of a living connection with the sacred and the archetypal dimensions of the psyche. He argued that psychology, as a discipline that explored the depths of the human soul, had a unique responsibility to help individuals rediscover the transformative power of religious experience and to create new forms of spirituality that were more adapted to the needs and challenges of the contemporary world. Jung’s vision of a new, more individualized and experiential form of religion, which he called “the religion of the future,” was based on his belief in the essential unity of the human psyche and the divine, and on the importance of integrating the insights of depth psychology into religious practice and belief. Jung’s approach to the relationship between psychology and religion, as a creative and transformative dialogue between the individual and the sacred, had a significant impact on the development of transpersonal psychology and the emergence of new forms of spirituality in the later 20th century, and continues to inspire contemporary efforts to bridge the gap between science and religion.

5.6 The Religion of Science

Carl Jung, while not formally trained in physics or mathematics, was deeply influenced by the revolutionary discoveries happening in those fields during his lifetime in early 20th century Switzerland. Close friendships and correspondences with luminaries like physicist Wolfgang Pauli and mathematician Albert Einstein, combined with the zeitgeist of groundbreaking scientific theories “in the air” around Jung, helped inspire his model of the psyche as a dynamic system of energy transfers and transformations. Drawing upon concepts like entropy, conservation and equilibrium, Jung saw in physics a metaphor for the movement of psychic energy from less to more probable states, always seeking stability and balance.

Jung contrasted two perspectives on interpreting chains of events, whether in physics or psychology: a causal-mechanistic view that traces present conditions to originating causes in the past, and a finalistic-energic view focused more on the abstract movement of energy toward end states of entropy and equilibrium. While more the determinist than the mystic, Jung saw the energic view as allowing for creativity and agency within the psyche, not just blind reactivity – unconscious complexes could autonomously press into consciousness in order to discharge their quantum of energy before settling back into their background state. This provided a way to acknowledge both the shaping impact of the past and the pull of the present context.

At a deeper level, Jung resonated with Pauli’s and Einstein’s sense of an emerging worldview that could reconcile long-standing divides between science and religion, matter and spirit, the literal and the symbolic. He saw mathematics and alchemy as parallel languages pointing to the same underlying mystery. Scholar David Tacey’s notion of a potential “third age” following eras of literal religious belief and then scientific materialism matched Jung’s intuition of a post-secular future that integrated meaning and empiricism, inner and outer worlds. Jung’s engagement with the physics and mathematics of his day was part of a lifelong effort to articulate this new synthesis.

6. Jung’s Later Explorations of Alchemy and Mysticism

6.1 The Significance of Alchemy for Jung’s Psychology of Religion

6.1.1 Alchemy as a symbolic language for the individuation process

In his later years, Jung became increasingly interested in the study of alchemy, which he saw as a rich symbolic language for the individuation process and the transformation of the God-image. Jung was fascinated by the alchemical quest for the philosopher’s stone, which he interpreted as a metaphor for the realization of the Self and the union of opposites. Jung saw alchemy as a pre-modern form of depth psychology, which used symbolic and mythological language to describe the inner workings of the psyche and the stages of spiritual transformation. Jung believed that the alchemical process, with its emphasis on the purification and transmutation of base matter into gold, mirrored the psychological process of individuation, in which the ego is transformed and integrated with the Self. Jung’s study of alchemy thus provided him with a rich symbolic language for articulating his understanding of the religious dimension of the psyche.

6.1.2 The alchemical opus as a metaphor for the transformation of the God-image

Jung’s interpretation of alchemy was closely tied to his understanding of the transformation of the God-image throughout the individuation process. Jung saw the alchemical opus, with its stages of nigredo (blackening), albedo (whitening), and rubedo (reddening), as a metaphor for the evolution of the God-image from a primitive and undifferentiated state to a more complex and integrated form. Jung believed that the alchemical process involved a confrontation with the Shadow and a dissolution of the ego, which mirrored the psychological process of integrating the unconscious and realizing the Self. Jung also saw the alchemical symbols of the hermaphrodite, the androgyne, and the sacred marriage as metaphors for the union of opposites and the reconciliation of the masculine and feminine aspects of the God-image. Jung’s use of alchemical symbolism thus deepened and enriched his understanding of the religious dimension of the psyche.

6.2 The Influence of Christian and Jewish Mysticism

6.2.1 Jung’s dialogue with Jewish mystics such as the Kabbalists and Hasidim

In addition to his study of alchemy, Jung was also deeply influenced by his dialogue with Jewish mystics, particularly the Kabbalists and Hasidim. Jung was fascinated by the Kabbalistic concept of the Ein Sof, the infinite and unknowable God beyond all images and attributes, and saw it as a powerful symbol of the Self and the collective unconscious. Jung also drew on the Kabbalistic doctrine of the Sefirot, the ten emanations or attributes of God, to develop his own understanding of the archetypes and the stages of the individuation process. Similarly, Jung was influenced by the Hasidic emphasis on joy, ecstatic prayer, and the immanence of God in all things, which he saw as a celebration of the numinous and transformative dimension of religious experience. Jung’s dialogue with Jewish mysticism thus expanded and deepened his understanding of the religious dimension of the psyche.

6.2.2 The incorporation of mystical concepts into his understanding of the God-image and the Self

Jung incorporated many concepts and symbols from Christian and Jewish mysticism into his understanding of the God-image and the Self. Jung was particularly influenced by the mystical concept of the “God beyond God,” the ineffable and transcendent dimension of the divine that lies beyond all human concepts and images. Jung saw this apophatic understanding of God as a powerful expression of the Self, the totality of the psyche that transcends the ego and the conscious personality. Jung also drew on the mystical concept of the “spark of the soul,” the divine element within the human person that is the source of spiritual awakening and transformation, to develop his own understanding of the individuation process and the realization of the Self. Jung’s incorporation of mystical concepts into his depth psychology thus provided a rich and nuanced understanding of the religious dimension of human experience.

6.3 The Culmination of Jung’s Religious Thought in Answer to Job

6.3.1 Jung’s psychological interpretation of the Book of Job

The culmination of Jung’s religious thought can be found in his book Answer to Job, in which he offered a psychological interpretation of the biblical story of Job and its implications for the understanding of God and evil. Jung saw the Book of Job as a profound exploration of the problem of innocent suffering and the relationship between God and humanity. Jung argued that the story of Job revealed the dark and amoral aspect of the God-image, the “God beyond good and evil” who is the source of both creation and destruction. Jung saw Job as a symbol of the individuated person who confronts the God-image and demands an answer for the existence of evil and suffering in the world. Jung’s interpretation of the Book of Job thus provided a psychological and theological foundation for his critique of traditional Christian theodicy and his call for a more honest and realistic approach to the problem of evil.

6.3.2 The implications of Answer to Job for Jung’s understanding of the God-image and the problem of evil

Jung’s Answer to Job had significant implications for his understanding of the God-image and the problem of evil. By emphasizing the dark and amoral aspect of the God-image, Jung challenged the traditional Christian understanding of God as a purely good and omnipotent being. Jung argued that the God-image contained both light and dark, good and evil, and that the confrontation with this paradoxical reality was a necessary aspect of the individuation process. Jung also saw the story of Job as a revelation of the ongoing evolution of the God-image, in which God becomes more conscious and responsible for the existence of evil in the world. Jung’s Answer to Job thus provided a psychological and theological framework for a more nuanced and realistic understanding of the religious dimension of human experience, and for a more honest and compassionate approach to the problem of evil.

7. Criticisms and Controversies

7.1 Criticisms of Jung’s Approach to Religion

7.1.1 Accusations of psychologism and reductionism

Jung’s approach to religion has been criticized by some theologians and religious thinkers for its apparent psychologism and reductionism. Critics argue that Jung’s interpretation of religious symbols and experiences in terms of psychological archetypes and processes reduces religion to a mere projection of the human psyche, and denies the objective reality and transcendence of the divine. Some critics also argue that Jung’s emphasis on the psychological and mythological significance of religious experience undermines the historical and doctrinal claims of traditional religions, and relativizes the truth claims of different religious traditions. These criticisms suggest that Jung’s approach to religion is ultimately a form of psychological reductionism that fails to do justice to the complexity and diversity of religious experience.

7.1.2 Critiques of Jung’s interpretation of religious texts and traditions

Jung’s interpretation of religious texts and traditions has also been criticized by some scholars for its apparent lack of historical and contextual sensitivity. Critics argue that Jung’s use of religious symbols and myths from different cultures and historical periods often ignores the specific social, political, and theological contexts in which these symbols and myths emerged, and imposes a universalizing psychological framework that obscures their particular meanings and functions. Some critics also argue that Jung’s interpretation of religious texts, such as the Book of Job or the Gnostic gospels, is often idiosyncratic and selective, and fails to engage with the broader scholarly debates and interpretive traditions surrounding these texts. These criticisms suggest that Jung’s approach to religion is ultimately a form of ahistorical and decontextualized interpretation that fails to do justice to the richness and diversity of religious traditions.

7.2 The Debate on the Scientific Status of Jung’s Psychology

7.2.1 Criticisms of Jung’s empirical methodology and lack of falsifiability

Jung’s psychology has also been criticized by some scientists and philosophers for its apparent lack of empirical rigor and falsifiability. Critics argue that Jung’s concepts, such as the collective unconscious and archetypes, are often vague and difficult to operationalize, and that his empirical evidence for these concepts is often anecdotal and unsystematic. Some critics also argue that Jung’s theory of synchronicity, which posits a meaningful and acausal connection between psychological states and external events, is ultimately unfalsifiable and unscientific, and that it relies on a selective and confirmation-biased interpretation of coincidences and chance events. These criticisms suggest that Jung’s psychology is ultimately a form of pseudoscience that fails to meet the standards of empirical verification and falsification.

7.2.2 Defenses of Jung’s approach as a “depth psychology” of religious experience